TALES AND TRADITIONS OF THE LOWER CAPE FEAR

Photo of steamship

TO THE MEMORY

OF

GEORGE DAVIS.

WHO, EVER UPHOLDING THE HONOR OF HIS NATIVE LAND,

MODESTLY EXEMPLIFIED IN HIS LONG, EVENTFUL LIFE

AND

STAINLESS REPUTATION,

THE IDEAL PATRIOT, JURIST, STATESMAN;

AND ABOVE ALL,

THE NOBLE CHRISTIAN GENTLEMAN,

THIS HUMBLE RECORD

OF HIS BELOVED CAPE FEAR

IS AFFECTIONATELY AND REVERENTLY INSCRIBED.

PREFACE.THIS little guide book, prepared perhaps too hastily, was undertaken six weeks ago as a compliment to Captain John W. Harper, of the Steamer “Wilmington,” by one who treasures the memories of the Lower Cape Fear, and who has tried to catch the vanishing lines of its history and traditions for the benefit of those who may not be unmindful of the annals of a brave and generous people.

WILMINGTON, N. C., 1ST MAY, 1896.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| The Southport Steamer | 9 |

| The First Steamboat on Cape Fear River | 12 |

| Settlement of Wilmington | 15 |

| Sanitary | 16 |

| Cape Fear Steamboats | 18 |

| Negro Head Point | 20 |

| Hilton Park | 23 |

| Market Dock and Ferry | 24 |

| Colonial Governor's Residence | 28 |

| Confederate States Cotton Press | 30 |

| Historic Mansion | 31 |

| United States Monitor Nantucket | 32 |

| Old Ship Yard | 33 |

| The Dram Tree | 35 |

| Hospital Point | 36 |

| Brunswick River, Mallory Creek and Clarendon Plantation | 38 |

| Old Town Settlement | 38 |

| Big Island | 39 |

| Rice Birds | 39 |

| First Navigators of the Cape Fear—King Watcoosa and his Daughters | 40 |

| Cushing's Exploits | 43 |

| Cushing's Daring Visit to Fort Anderson | 46 |

| Carolina Beach | 48 |

| Gander Hall | 49 |

| Sedgeley Abbey | 50 |

| First White Settlement | 52 |

| TABLE OF CONTENTS—CONTINUED. | |

| PAGE. | |

| Cape Fear Indians | 54 |

| Lilliput | 55 |

| Kendal | 58 |

| Orton | 61 |

| Colonial Governor Tryon's Palace—Scene of the First Outbreak of the Revolutionary War | 67 |

| Ruins of Brunswick | 72 |

| Ruins of St. Philip's Church | 73 |

| Colonial Ferry and Inn | 75 |

| Confederate Fortifications | 77 |

| Fort Anderson | 78 |

| A Colonial Fort | 80 |

| Fort Fisher | 83 |

| Description of Situation | 83 |

| Land Face of Fort Fisher | 86 |

| Sea Face of Fort Fisher | 88 |

| The Fort Fisher Fight | 90 |

| Craig's Landing | 97 |

| The Heroine of Confederate Point | 98 |

| Butler's Powder Ship | 107 |

| The Rocks—Closure of the Inlet | 109 |

| Battery Lamb—Confederate Salt Works | 111 |

| Snow Marsh—Dredging Steamer “Cape Fear” | 112 |

| Price's Creek Lighthouse Confederate States Signal Station | 114 |

| Wilmington and Charleston Mail Boats | 117 |

| Cape Fear Quarantine Station | 119 |

| Southport—Governor Smith—Cape Fear Pilots | 122 |

| Bald Head Pirates | 125 |

| Fort Caswell | 128 |

| Evacuation and Explosion of Fort Caswell | 131 |

| War Department Records—Forts Johnston and Caswell | 134 |

| Fort Johnston, North Carolina | 135 |

| TABLE OF CONTENTS—CONCLUDED. | |

| PAGE. | |

| Wild Pigeons—Wreck of Spanish Ship—Probable Murder—Treasure Trove | 140 |

| Life Savers | 143 |

| A Run to Sea | 144 |

| Captain Fry and the Cuban War | 145 |

| Cape Fear Privateers in the War of 1812 and 1861 | 154 |

| Blockade Runners | 162 |

| Maffitt's Experience | 166 |

| Blockade Runner “Don” | 184 |

| Pilots in a Storm | 205 |

| Homeward Bound | 213 |

| Advertisements | I to LXII |

THE steamer “Wilmington” is a model of marine architecture, combining spacious and comfortable passenger accommodations with the greatest speed attained by steam craft on the Cape Fear river. Her clean decks and tidy saloons afford the bracing outside air, or the restful seclusion which invites repose. The daily run to and from Southport is made in two hours, including all river landings; and the object of this little book is to interest and amuse the traveller by a concise description of Wilmington business enterprise and local scenery, contrasting the record of the present busy age with the history and traditions of long ago.

As we approach the gangway of this stately steamer, we are impressed with the quiet of the scene. We miss, most gratefully, the noisy roar of escaping steam, the confusing shouts, the imprecations and jostlings of the professional baggage-smasher, and all the other distasteful and offensive features of former days. We are promptly met by the Commander and owner, a dignified, stalwart specimen of the American sailor and gentleman, who receives us courteously, and who welcomes us with

unmistakable cordiality. His name is John W. Harper, and he is said to be the favorite skipper of North Carolina. When you have made the round trip in his charge you will not doubt his title to that honorable distinction. A successful steamboat captain should be competent, cool, cantious, patient, polite and amiable to the last degree; with an infinite reserve stock of never failing good humor. These attributes are possessed by Captain Harper, to an unusual extent, which combined with a large experience, inspire confidence and insure safety. He has been running boats up and down the river for twenty-two years, and he has made, during that time, more than thirteen thousand trips between Wilmington and Southport—equal to fifteen trips around the world. He was the pioneer of the regular summer excursions to the Cape Fear seacoast, by which thousands of weary people and sick babies from the up country and the city, oppressed with midsummer heat, have been refreshed and strengthened by ocean breezes and salt water at a nominal expense. It is a matter of fact that salt sea air will often do more good to a sick, puny child than any of the medical remedies in the pharmacopœia. Many anxious, worn-out mothers, have had reason to bless Captain Harper as the means under Providence of restoring to health their sick or feeble little ones. A beloved

physician has often said that daily trips from Wilmington to Southport are even more beneficial to sick children than a residence on the seashore. The gliding motion of the boat soothes them, the clear, fresh air of the river invigorates and strengthens them, and the entire freedom from dust and grime which is so disagreeable and hurtful on railroad journeys brings grateful sensations of cleanliness and comfort to young and old alike.

“How happy theyWho from the toil and tumult of their livesSteal to look down where naught but ocean strives.”The First Steamboat on the

Cape Fear River.

The First Steamboat on the

Cape Fear River.

LET us contrast the swift steamer Wilmington with the ridiculous example of former days—let us turn back for three-quarters of a century, when the town of Wilmington contained only a tenth of its present population, and recall an incident, related to the writer by our venerable townsman. Col. J. G. Burr, which created the

greatest excitement at the time, and which was the occasion of the wildest exuberance of feeling among the usually staid inhabitants of the town—the arrival of the first steamboat in the Cape Fear River. A joint stock company had been formed for the purpose of having one built to ply between Wilmington and Smithville or Wilmington and Fayetteville. Captain Otway Burns, of Privateer “Snap Dragon” fame, during the war of 1812, was the contractor. The boat was built at Beaufort, where he resided. When the company was informed that the steamer was finished and ready for delivery, they despatched Captain Thomas N. Gautier, an old sea captain, and a worthy citizen of the town, to take command and bring her to her destined port. Expectations were on tiptoe after the departure of the Captain; a feverish excitement existed in the community, which daily increased, as nothing was heard from him for a time, owing to the irregularity of the mails; but early one morning this anxiety broke into the wildest enthusiasm when it was announced that the “Prometheus” was in the river and had turned the Dram Tree. Bells were rung, cannon fired, and the entire population, without regard to age, sex or color, thronged the wharves to welcome her arrival. The tide was at the ebb, and the struggle between the advancing steamer and the fierce current was a desperate one; for

she panted fearfully, as though wind-blown and exhausted; she could be seen in the distance, enveloped in smoke, and the scream of her high pressure engine reverberated through the woods, while she slowly but surely crept along. As she neared Market Dock, where the steamer Wilmington is at present moored, the old Captain, gorgeously arrayed in brilliant uniform, with cocked hat and epaulettes, made his appearance near the engine room, in full view of the excited crowd, and applying his speaking-trumpet, his symbol of authority, to his lips, bellowed to the engineer below, in a voice that sounded like the roar of some hoarse monster of the deep: “Give it to her, Snyder”; and while Snyder gave her all the steam she could bear, the laboring “Prometheus” snorted by amid the cheers of the excited multitude. In those days the river traffic was sustained by sailing sloops and small schooners, with limited passenger accommodations and less comfort. The schedule time to Smithville (now called Southport), was four hours, wind and weather permitting, and the fare was one dollar each way.

Settlement of Wilmington.ABOUT the year 1730, some five years after the town of Brunswick was established fourteen miles lower down the river, a few settlers built their humble habitations on a bluff in the midst of the primeval forest now known as Dickinson Hill, nearly opposite the junction of the Northeast and Northwest branches of the Cape Fear river, which was then known as the Clarendon river. Their purpose was to find a safer harbor than the exposed roadstead of Brunswick, and to secure a larger share of the river traffic from the up country, which was then very profitable.

In a few months this hamlet increased to the proportion of a small village, without order or regularity, which was named New Liverpool.

In 1733 it was surveyed into town lots, although the inhabitants had no legal right to the land.

In the same year John Watson obtained a Royal grant of 640 acres of land on the East side of the Northeast branch of the river called the Cape Fear, in which was included the site of the village or town called New Liverpool, but latterly known as Newton.

In 1739, through the influence of the Colonial Governor, Gabriel Johnston, the name was again changed to

Wilmington, in honor of Spencer Compton, Baron Wilmington, an influential English friend of the Governor. In 1760 King George II. made the town a borough, with the right of sending a member to the Assembly.

Arthur Dobbs was then the Royal Governor, and he lived at Russelboro, which is now a part of Orton plantation.

In 1763, George III. being King, additional rights were granted by the Crown, the corporate title being made “The Mayor, Recorder and Aldermen of the Borough of Wilmington.”

In 1776 the corporate name was changed to that of “The Commissioners of the Town of Wilmington”; and this name was continued for one hundred years. The present corporate name, “The City of Wilmington,” was acquired in the year 1866.

Sanitary.ARTIFICIAL drainage has in recent years carried the storm water from the city into the tributary streams of the Cape Fear, and if maintained in proper condition, is well designed to effectually drain a large area which was formerly the most unhealthy quarter of the settlement.

As a result malarial fever has greatly decreased in the last twenty years, and it may be truly said, although stigmatized forty years ago as the sailor's grave, and shunned by the people of the up country as an unsafe place in which to tarry all night during the summer and autumn, it has become exceptionally healthy. As an evidence of this, the death-rate for several years past has been much smaller than in the surrounding country; and compares favorably with the most favored towns of its size on the Atlantic coast—the annual deathrate being about seventeen to the thousand.

Drainage has not, and cannot, it is true, alter the malarial influence upon crews of vessels sleeping on the river in the months of July, August, September and October. This standing menace to the prosperity of our shipping, as evidenced by the scarcity of tonnage during these months, has been seriously considered for many years, and a remedy actually devised. The difficulty has been to impress the lesson of prevention, learned at such a cost, upon the interested parties. The State Board of Health has done much towards inculcating important advice upon the subject. For many years it has been known, as well by the people as by the doctors, that the fevers occurring among the vessels in our tidewater streams were preventable in a marked degree.

Observations extending over a space of time marked by four or five generations demonstrated that the cause of sickness among sailors was due very largely to sleeping on board of vessels in the Cape Fear river particularly. This fact was so firmly established in the opinion of merchants in Wilmington, that $20,000 was subscribed to build a home for seamen, in which they might find a safe retreat from the effluvia of the river, and what is not exactly pertinent to the present subject, to escape also the abominable effluvia of low sailor lodgings. In this building ample provision was made for more sailors than ever visit the port of Wilmington at one time, and by the Christian benevolence of Capt. Gilbert Potter, one of the oldest citizens of our city, who had himself been a sea-captain, a house of worship, supplied by the yearly ministrations of a preacher, was provided, to throw around these “toilers of the sea” a beneficent influence.

Cape Fear Steamboats.BEFORE railroads were so numerous and the means of transportation limited, the Cape Fear River Steamboat Company enjoyed a large share of public patronage. The merchandise for the merchants of Western North Carolina, East Tennessee and portions of South Carolina,

Georgia and Virginia was brought to this port by vessels, transferred to the river boats to Fayetteville, and then forwarded to destination by the slow, tedious and expensive means of transportation by wagons. Fayetteville in those days was a place of as much business and importance in a commercial point of view as any inland town in the country, and every citizen in the place took pride in seeing the place flourish and prosper. The merchants built steamboats and plank-roads, and in this way fostered the trade which from the position at the head of navigation was a natural outlet. But as soon as the railroad became the grand artery to receive and disperse everything as public and private interest directed, the river traffic decreased, and with its decline the plank-roads ceased to be profitable, and there was almost a total disappearance of the white-covered caravans that plied between the mountains and the Cape Fear country.

The Worths, Lutterlohs, Orrells and others had regular fleets on the Cape Fear. We now recall the steamers Rowan, Henrietta, Chatham, Gov. Graham, Flora McDonald, A. P. Hurt and Gov. Worth, commanded by captains Roderick McRae, A. P. Hurt, Sam Skinner, A. H. Worth; the steamers Brothers, James R. Grist, Douglass, J. T. Petteway and Scottish Chief, all of which boats were at times under the command of

that whole-souled, jovial Scotchman, “Uncle Johnnie Banks”; the steamer Sun, Captain Rush; the steamer Enterprise, Captain Datus Jones; the Fannie Lutterloh, Captain Stedman; the Kate McLaurin, Captain Daily; the Black River, Captain Jesse Dicksey; the John Dawson, Captain Lawton; the Hattie Hart, Captain Peck; and other steamers and captains we cannot now recall. In these later days there has been employed in the river trade the steamers Murchison, the North State, the Cumberland, the Juniper, the Cape Fear, the Wave, the J. C. Stewart, the Frank Sessoms, commanded by captains Garrason, Smith, Green, Worth, McLauchlin and the Robesons.

Negro Head Point.AS the “Wilmington” lies at her wharf, near Market Dock, we see from her spacious upper deck Negro Head Point, which divides the waters of the Cape Fear into Northwest and Northeast branches. It is the Northern limit of the jurisdiction of the Board of Commissioners of Navigation and Pilotage, and its name is derived from a melancholy incident in the time of slavery.

In the latter part of the year 1831, through the influence of Northern emissaries, an insurrection of Negro

slaves occurred in Southampton, Virginia, which spread rapidly into this State, creating great and general excitement.

A number of helpless white women and children fell victims to the madness of the blacks, which so infuriated the whites that a race war seemed inevitable. All the approaches to the town of Wilmington were heavily guarded by the militia, and two companies of United States troops, numbering 170 men, from Fortress Monroe, remained on duty here for several months. The uprising was overcome and the leaders suffered death. Four were hanged near Giblem Lodge, on Princess street; several others were shot, and, according to the barbarous custom of those days, their heads, after decapitation, were placed on poles in conspicuous places as a warning to others like minded.

At the intersection of Market and Front streets, a few rods from the steamer's dock, stood the town market house, where the slave-trade was constantly carried on until 1863.

We draw a veil over the sad scenes enacted there, but we recall the fact that it was not until after the slave-traders of the North had received full value of their human merchandise from their Southern brethren that our neighbors began to realize the enormity of the institution.

And yet our people who were impoverished by its downfall would not, if they could, deprive the negro of his freedom.

With reference to the introduction of slavery into Carolina by the Colonial Governor, Yeamans, from Barbadoes, in 1671, the late lamented George Davis said:

“This seems to be a simple announcement of a very commonplace fact; but it was the little cloud no bigger than a man's hand. It was the most portentous event of all our early history. For he carried with him from Barbadoes his negro slaves; and that was the first introduction of African slavery into Carolina.—(Bancroft, 2,170; Rivers, 169.)

“If, as he sat by the camp-fire in that lonely Southern wilderness, he could have gazed with prophetic vision down the vista of two hundred years, and seen the stormy and tragic end of that of which he was then so quietly inaugurating the beginning, must he not have exclaimed with Ophelia, as she beheld the wreck of her heart's young love:

“ ‘O, woe is me! To have seen what I have seen, see what I see’ ”!

Hilton Park.Hilton Park.

JUST beyond Negro Head Point, on the Northeast branch, a beautiful wooded bluff may be seen. It is Hilton, named in honor of one of the three first explorers from Barbadoes who visited the Cape Fear in the year 1663, which became famous in Revolutionary history as the home of Cornelius Harnett, a prominent patriot of this section and conspicuous, noted personage of his day. Until a few years ago his house, a neat Colonial structure, embowered by noble oaks, and subsequently owned by the Hill family, was our most interesting

relic of Revolutionary times; but the estate passed into other hands, and this picturesque, historic home was demolished, to the shame of our people, who were offered the building, as a public gift, for the cost of its removal and preservation.

“A perfect woman, nobly planned,” whose skill and virtues are of national reputation, and whose ancestors were always leaders on the Cape Fear, has happily devised, as President of the Society of Colonial Dames, the means of placing a public monument over the grave of this sturdy patriot whose dust long since mingled with its mother earth in old St. James’ churchyard, ere his noble sacrifice of life to liberty was appropriately recognized.

Market Dock and Ferry.THE old Market Dock, at which the “Wilmington” is moored, is worthy of passing notice. During the Revolutionary war, while the town of Wilmington was in possession of the British troops under Major Craig, an American soldier in ambush on Point Petre or Negro Head shot with a long-range rifle a number of British troopers standing at Market Dock.

Also, more than a hundred years afterwards, when the Federal troops under Schofield and Terry reached the

Brunswick side of Market Dock ferry on their way to Wilmington, the last stand of the Confederate troops was made near Market Dock; a detachment of light artillery having fired from this point upon the advancing Federals on the west side of the river and checked their progress. The Federals were in overwhelming numbers, however, and the artillerists soon followed Bragg's retreating forces before the invaders reached the town.

The Confederates had carefully removed from the west shore all boats and other means of transportation to the Wilmington side in order to retard the Federal advance. Consequently there was considerable delay in crossing the river, which was at last overcome by a demented Wilmington woman, who secretly obtained a small boat and paddled it across to the Federals, by means of which other craft was soon floated, and the town for a second time invested by a hostile army.

In the early morning of the 22d February, 1865, a Confederate officer in command of the last battalion of infantry to leave Wilmington when evacuated by the Southern troops, was leading his men along Fourth street on his way to rejoin General Hoke, who had passed up to the North East River the night previous. Saddened and wofully depressed with the thought of leaving all his loved ones to the mercy of enemies, he

called the next officer, and, giving him orders about the route to march, turned back from Boney Bridge to hurriedly bid adieu to all the dear ones. Passing down Red Cross to Front, hurried visits were made to several friends, but on reaching the intersection of Market and Front streets, the proximity of the enemy was apparent, for there were gathered the Mayor and Aldermen of the city—John Dawson, W. S. Anderson, P. W. Fanning and others of the citizens who had there met to turn over the keys of the city to the captors. Around on every side were seen the results of the cannonfiring of the day previous, the window-panes in every house were shattered and artillery debris lay scattered around. Immediate passing events urged a very prompt retreat, and the officer hurried to his father's house to say good-bye and to receive their loving blessings and wishes for safety. Hastening through this distressing scene, he began his journey to rejoin his command, accompanied as far as Boney Bridge by his sister. The streets of Pompeii or Herculaneum when buried beneath the lava of Vesuvius were no quieter than those of Wilmington. Not a soul was to be seen on the streets, not a window-blind but was closed. Apparently even the dogs were affected by the prevailing distress. The mournful walk was continued, and the officer, parting

with his sister, continued his march with feelings easily to be imagined, and soon rejoined his command about five miles out. This lady subsequently said that this was the loneliest walk of her life-time. She met no one between Boney Bridge and her father's residence, South of Market street on Second street.

Colonial Governor's Residence.

(Lord Cornwallis’ Headquarters.)

A FEW steps from the “Wilmington's” wharf is an unpretentious tobacconist's shop—a small brick building—which is said to have been the residence of the celebrated Colonial Governor, William Tryon, who was closely identified with the Cape Fear section of Revolutionary

(Confederate General's Headquarters.)

times, as will be seen further on. Higher up, on the corner of Third Street, may be seen the fine residence, which served as the headquarters of General Lord Cornwallis, commander of the British forces. It is now owned and occupied by Mrs. McRary. Immediately opposite stands an ancient residence of the DeRosset family, which was used throughout the civil war nearly a hundred years later as headquarters of the Confederate Generals commanding this district.

Confederate States Cotton Press.

AS we leave the wharf, on our passage down the river, we see a conspicuous relic of an extraordinary era in the foreign trade of Wilmington. It is the leaning, but unbroken, brick chimney of the Confederate States Cotton Press established here in the year 1864. This press was the first in Wilmington, and had a capacity of 500 bales a day. The wharves and marsh adjoining to the warehouses were piled with enormous quantities of cotton bales belonging to the Confederate Government, and hither came all the swift blockade-runners for cargoes which were laden with great rapidity; work went on day and night, as many as twenty steamers loading together. The entire plant, together with several thousand bales of cotton was destroyed by fire by order of General Bragg upon his evacuation of this place on the evening of February 21st, 1865.

Historic Mansion.Historic Mansion.

ON the East bank at a considerable elevation above the river is an historic residence. It was built and occupied by the first Governor of North Carolina elected by the people, Edward B. Dudley, a statesman of liberal and patriotic views, of commanding presence and of most amiable manners. His name should ever be held in grateful remembrance by our people, for he was a leader in every public and private work for the

benefit and prosperity of Wilmington, and contributed $25,000 towards the building of the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad, of which he was the first President. He was a man of generous impulses and stainless integrity, beloved and honored by rich and poor, and by white and black alike. He served as a member of the Twenty-first Congress, to which he was elected in the year 1829, but declined re-election, because he said Congress was not the place for an honest man.

In May, 1849, he entertained at this residence the distinguished Daniel Webster, who visited Wilmington as his guest. Mr. Webster was doubtless well cared for, as he wrote to a friend May 7th: “We are grandly lodged in the Governor's mansion.”

In later years Cardinal Gibbons, with an Archbishop and twelve bishops were entertained here by Mr. Kerchner, who owned the place at that time.

The present owner and occupant has greatly enlarged and improved this property, at the foot of which may be seen the

United States Monitor Nantucket.A battle-scarred survivor of the war between the States. This vessel took part in the bombardment of Fort Sumter and in other conflicts at sea. Her turret

is indented by hostile shot and shell, and she is regarded as an interesting type of the old navy. The “Nantucket” is in charge of the Wilmington Division of North Carolina Naval Reserves, and is used as the school ship of this fine organization.

Old Ship-Yard.THE first and only sailing ship built at Wilmington was launched June 5th, 1833, by Mr. John K. McIlhenny, and named after his two daughters, “Eliza and Susan.” The work was done by Mr. Josh Toomer, the grandfather of the present generation of that name, under the direction of Mr. McIlhenny, at the saw mill of the latter upon the exact site of Kidder's mill. Mr. McIlhenny owned a rice mill and a saw mill, both of which were about the first erected at Wilmington.

The “Eliza and Susan” was a full-rig ship of 316 tons, built of the staunchest live oak, and of unusual strength. The oak came partly from Bald Head and partly from Lockwood's Folly. She was pine-planked and coppered. It is not certain what cargo she took out, but she came back loaded with salt. The commander

was Captain Huntington, already in middle life at the time of the ship's first voyage. His son afterwards married Miss Brown of this place.

Long afterwards, while the “Eliza and Susan” was engaged in the whaling trade of the Pacific, Captain Thomas F. Peck, who had gone from Wilmington to the land of gold with the “forty-niners,” saw the familiar Wilmington ship at anchor in San Francisco bay. He was subsequently invited on board and served with a glass of Cape Fear river water, then highly esteemed as pure and wholesome, which had been kept in one of the reserve tanks for more than twenty years.

At right angles with the river and parallel with Queen street Mr. McIlhenny cut a canal; at the head of this canal the ship was built. In launching her she stuck in the mud, and Colonel McIlhenny remembers as a boy seeing his father fume most vigorously about it. There were on the river about that time the “Enterprise,” the “Spray,” the “John Walker” and the “Henrietta.” Mr. McIlhenny and Governor Dudley owned the “Enterprise,” which was a very small boat, and was used by them for towing the rice flats from the different plantations. They lengthened her first ten or twelve feet, then afterwards gave her an additional

length and ran her as a passenger boat from Wilmington to Smithville.

The “Spray” ran about 1853 or 1854, and was the fastest of them all. She was shaped something like a barrel, hooped up on the sides. She was the favorite steamboat plying between Wilmington and Smithville a few years before the war.

Mr. McIlhenny was awarded a contract by the Government to furnish timber for building the United States man-of-war “Pennsylvania.” No large ships were built here subsequently. Mr. B. W. Beery built some schooners and pilot boats, and afterwards Mr. Cassidy established the ship-yard now conducted by Captain S. W. Skinner, the only ship-yard in Wilmington.

The Dram Tree.LOOKING ahead to the farthest point in view, we distinguish an object, the passing of which was signalized in “ye olden time” by the popping of corks or by other demonstration of a convivial nature. It is an old cypress tree, moss-covered and battered by the storms of centuries. Like a grim sentinel, it stands to warn the out-going mariner that his voyage has begun,

and to welcome the in-coming storm-tossed sailor to the quiet harbor beyond. Its name is significant. It is called the Dram Tree, and it has borne this name for more than a hundred years. For further particulars see Captain Harper.

Hospital Point.WE now pass Hospital Point, whereon was placed a pest house during the small-pox plague which followed Sherman's army. Many thousands of negro refugees fell victims to this dread disease. At low water may be seen the charred remains of several Confederate war vessels which composed Commodore Lynch's small and crippled fleet, and which were burned by the Confederates when Wilmington was evacuated after the fall of Fort Fisher.

This place is also known as Mount Tirzah, and it is the property of the Seamen's Friend Society of Wilmington. In 1835 the citizens of the town held a meeting to establish the Wilmington Marine Hospital for the benefit of sick seamen in this port for whom no provision up to that time had been made. Subscriptions were raised, a society formed, and the Mount Tirzah

property of 150 acres and several houses standing thereon purchased from Governor E. B. Dudley for one thousand dollars.

The principal building, a house of two stories, was converted into a hospital and managed by the Marine Hospital Society until April 24th, 1855, when this property and the other assets of the Society were transferred to the Seamen's Friend Society, which undertook to carry on the work in conjunction with its own benevolent enterprise in the port of Wilmington. Later on the United States Government established in the Southeastern part of the town a fine marine hospital, which provided greatly improved quarters and treatment for sick seamen, and which is now one of the most interesting features of the port of Wilmington.

The Mount Tirzah property is occasionally used by the City Government for the isolation and treatment of cases of infectious diseases.

Brunswick River—Mallory Creek—

Clarendon Plantation.

ON the West side is the mouth of Brunswick River, still partly obstructed by Confederate torpedoes.

Mallory Creek is some distance lower down. Near it is “Clarendon,” a fine rice plantation, originally owned by Marsden Campbell and afterwards the property of William Watters, Esq., a Cape Fear gentleman of the Old School, and a planter of large experience. It is now owned by Messrs. Fred Kidder and H. Walters.

Old Town Settlement.PASSING Barnard's Creek on the East side, near which in the olden time were several valuable plantations, we come to Town Creek, where 800 colonists from Barbadoes, led by Sir John Yeamans, built a town in the year 1665 and called it Charlestown in honor of the reigning sovereign of England, King Charles II.

Sir John had been a loyal adherent of the deposed King, and was rewarded upon the Restoration with the order of Knighthood and a royal grant of lands in Carolina. He is said to have been the first British

Governor of Clarendon, which extended originally from Albemarle to St. Augustine, Florida. The settlement did not prosper. In a few years the colonists abandoned it and removed, some to Charleston, S. C., others to Albemarle, in the North. Not a white man remained, and the river land continued in possession of the Indians for many years after.

Big Island—Rice Birds.ABOUT a mile below Old Town is Big Island, a tract of nearly 300 acres of rich alluvial soil, which the first voyagers to the Cape Fear in 1663 named Crane Island, and which is charted by the United States Coast Survey as Campbell's Island. It was formerly a light-house station, but the light was discontinued during the late war and a battery erected in its place. There is a fortune in this island waiting for some enterprising truck farmer, as the State Geologist says it contains some of the richest lands in the South, that will never need fertilizing. Millions of fat rice birds roost here at night after preying upon the milky rice of the neighboring plantations during the day. It is estimated that these toothsome little pests devour 25 per cent. of all the rice made on

the Cape Fear. They appear every Fall together on the same day and depart during a single night when the rice gets too hard for them. The planters have never been able to protect their crops from the yearly ravages of these birds. Although a gang of boys and men are kept firing guns at them all day, a very small proportion of the immense droves is killed. For a dainty supper, a fat rice bird is perhaps the most delicious morsel that ever tickled the palate of an epicure.

First Navigators of the Cape Fear.King Watcoosa and His Daughters.

THE first reference made in history to Big Island is in the report of the Commissioners sent from Barbadoes in October, 1663, to explore the river Cape Fear.

After describing the voyage to the Cape, they say that the channel is on the East side by the Cape shore, and that it lies close aboard the Cape land, being 18 feet at high water in the shallowest place in the channel, just at the entrance, but that as soon as this shallow place is passed, a half cable length inward, thirty and thirty-five feet water is found, which continues that depth for twenty-one miles, when the river becomes shallower

until there is only twenty-feet depth running down to ten feet (where Wilmington now stands).

These bold voyagers brought their vessel some distance higher than Wilmington, and were much pleased with the land on the main river above Point Petre.

They found many Indians living on their plantations of corn, which were also well stocked with fat cattle and hogs stolen from the Massachusetts settlers of 1660 on the Cape opposite Orton Point. Game was very abundant, and fish was also plentiful. During an expedition higher up in a small boat, they killed four swan, ten geese, ten turkeys, forty ducks, thirty-six paraquitos and seventy plover.

They were attacked by Indians once; a display of fire-arms afterwards compelled the peaceful recognition of the natives. And when the ship reached Crane Island (now Big Island) on the return, Sunday, 29th November, 1663, they met the first ruler of the “Cape Fear Country,” the Indian Chief Watcoosa, who sold the river and land to the Barbadians, Anthony Long, William Hilton and Peter Fabian.

A ludicrous incident which the virtuous Barbadians took very seriously occurred during their negotiations. The King, Watcoosa, accompanied by forty lusty warriors, made a long speech to them, which, although unintelligible to the white men, was undoubtedly of a

peaceful nature, as he indicated by pantomime that he would cut off the heads of any of his people who attempted to injure them, and in testimony of his goodwill, at the conclusion of his discourse he presented to the Barbadian Captain two very handsome and proper young Indian women, whom the voyagers were given to understand were the King's daughters. These guileless maidens of the Cape Fear, whom Hilton describes as the tallest and most beautiful women he ever saw, were not at all shy, but forced their way into the white men's boat and refused to leave it. Captain Hilton probably had a wife at home, and the thought of presenting these two beautiful girls in their native costume to his better half in Barbadoes must have appalled the stout-hearted explorer who had already faced so many lesser dangers. He loaded them with presents; he gallantly entreated them to call again, but they laughingly shook their heads, and pointing to the ship, indicated their purpose to remain with him for better for worse. What was the poor man to do? Worse still, thought the Captain, what will Mrs. Hilton do! He met the emergency as little George Washington did not do. He presented to the father a little hatchet, and he told him a lie. He promised to take the girls aboard in four days; but, alas! their names do not appear later in the passenger-list

for the homeward voyage. It is said that for many years after, these disappointed maidens might be seen on the Cape lands shading their eyes as they gazed towards the Southern horizon, looking in vain for the return of the perfidious Hilton, who wisely remained at home when the colonists came to settle on Old Town Creek.

Cushing's Exploits.OPPOSITE Big Island, on the East side, is Todd's Creek, known as also Mott's Creek, which was the scene of Lieut. William B. Cushing's brave exploit June 23d, 1864. This gallant young naval officer perhaps accomplished more by personal valor than any other individual on either side during the war.

At half-past seven o'clock on the night of May 6th, 1864, the Confederate iron-clad “Raleigh,” which was built at the foot of Church street, in Wilmington, proceeded down the river in company with several other smaller boats composing the puny fleet of Commodore Lynch, and under the command of Lieut. J. Pembroke Jones, C. S. N., crossed the New Inlet bar and attacked the blockading fleet. The Federals were taken by

surprise, and after a feeble resistance took flight, the “Raleigh” having damaged one or two of the blockaders by her well-directed fire. The Ram was too unwieldy for service at sea, however, and on the second day out Commodore Lynch ordered her back to the river. After crossing the Inlet she stuck on the Rip Shoal and sunk, where she still remains buried in the sand. Lieut. Cushing, then attached to one of the blockaders, the United States steamer “Monticello,” with his usual zeal and fearlessness, volunteered to attempt the destruction of the “Raleigh,” whose fate was unknown to the Federals. He also undertook a reconnoissance of the defences of the Cape Fear River for the information of the United States Government, which was then preparing an expedition for the capture of Wilmington. Notwithstanding the warning of his superiors that he was almost certain to be captured or killed in this adventure, he persisted in his scheme, and on the night of June 23d, 1864, left his vessel in the first cutter, accompanied by two subordinate officers and fifteen men, crossed the western bar and passed the forts and town of Smithville without discovery, but was very nearly run down by an outward-bound blockade-runner. He then proceeded fearlessly up the river, and with muffled oars steered his boat immediately under the guns of Fort Anderson.

As Cushing attempted to leave Fort Anderson the moon came out from the clouds and disclosed the party to the sentinels, who hailed and immediately opened fire. The fort was roused and the confusion general. Cushing boldly pulled for the opposite banks and swiftly disappeared along the other shore.

His next stopping-place was in this creek, up which he poled his boat until he came to the military road leading from Wilmington to Fort Fisher. Here he cut the telegraph wire and captured a courier from General Whiting with despatches for Colonel Lamb at Fort Fisher. He then put one of his officers (Howorth) in the Confederate's uniform and dispatched him in broad daylight to Wilmington for supplies.

Howorth returned a few hours after with a liberal supply of chickens, eggs and butter, which he had bought without attracting any suspicion. Cushing then waited for darkness, and it is said went in person and also in the courier's clothes to Wilmington, and proceeded to his aunt's house, corner of Eighth and Market streets, where he peeped through the window-blinds and recognized his Confederate kinsfolk, who were of course not made aware of his presence.

On the following day he made sketches of the fortifications around Wilmington and captured a boat-load of Confederates, from whom he learned the fate of the

“Raleigh,” which he subsequently inspected in person. He next put his prisoners (six men) into a boat without oars or sails and sent them adrift to get home as best they could. Proceeding down the river, he carefully inspected the torpedo obstructions, and attempted the capture of the Confederate guard-boat near New Inlet. Here he met with formidable resistance, four boats having pursued him, and he was obliged to dash into the breakers on Carolina shoals to escape a large force of Confederates. He reached the blockading squadron safely after an absence of two days and three nights.

His subsequent destruction of the Confederate Ram “Albemarle” is doubtless one of the bravest examples of personal valour in military history.

Cushing's Daring Visit toFort Anderson.

AT early dawn on Friday, February 17th, 1865, the Federal fleet in the river began to bombard Fort Anderson, while the troops under General Schofield attacked the land force and the lines extending westward. The bombardment was kept up all day long with great fury, but the firing ceased at sundown.

About eight o'clock that night the “Eutaw Band,” attached to the 25th S. C. Regiment (Colonel C. H. Simonton commanding) came into the Fort and gave a serenade complimentary to the commanding officer (Colonel John J. Hedrick, 40th N. C. Regiment) and his officers. Colonel John D. Taylor was requested by Colonel Hedrick to return thanks to the band, and while he was doing so in a neat and appropriate speech, the officer of the day reported that a boat had been seen passing the Fort and going into the cove on the North side of the Fort. Soon after the speaking the boat was seen pulling out into the river. Captain E. S. Martin had seen the boat going up the river and ordered that the heavy shot be withdrawn from several guns and grape-shot substituted; and when the boat was seen going down the river he ordered the guns fired at it. The boat responded with small arms, and the crew escaped and notified those in the Fort of their safe arrival at the fleet by a single rocket that shot up into the air, and the Confederates heard nothing more of it at that time.

On the 9th or 10th of March, 1865, the same troops which were in the Fort the night above mentioned were at Kinston, N. C., resisting the advance of General Cox's command from New Berne to Goldsboro. The advance guard of General Cox was captured and one of the

prisoners gave a Confederate officer a copy of the “New York Herald,” which contained an account of a visit made by Captain Cushing to Fort Anderson. He stated that he commanded the boat above mentioned, and had passed into the cove above the Fort, landed and gone into the Fort while Colonel Taylor was speaking. He had hidden himself under one of the guns (which was not in use) on the opposite side of the Fort, about 75 or 100 feet from the speaker, and heard the rest of his speech, which was reported in the account of this visit. The officer (Captain Martin) into whose hands the “Herald” came, having heard the speech of Colonel Taylor, recognized the report as accurate in every particular.

The account also described the escape of Captain Cushing from the Fort and of the boat from the fire of the Confederate guns, and his safe return to his vessel below the Fort.

Carolina Beach.THE next point of interest on the East side is the wharf of the New Hanover Transit Company, from which there is a short railroad connection of about two miles to the favorite seaside resort, Carolina Beach.

This place was long known to a few of our people as the finest and safest beach on the Atlantic coast, but generation after generation of our inhabitants lived and died without having seen the beautiful foaming breakers curling over these hard white sands, which extend for five miles along this exquisite shore. Before the Wilmington and Wrightsville turnpike was thought of, and long years prior to the building of the Seacoast Railroad, Captain Harper undertook to bring in the steam yacht “Passport” thousands of excursionists from Wilmington and the interior to the health-giving breakers at such a trifling expense, that the humblest and poorest might enjoy the pleasures of surf-bathing, which had hitherto been the exclusive privilege of the rich, until the number has increased to forty and fifty thousand passengers annually.

The steamer “Wilmington” makes four or five trips daily, and the run occupies one hour from Wilmington to the beach.

Gander Hall.NEAR this landing may be seen a fine grove of old oaks which many years ago sheltered an attractive estate, still known as Gander Hall. It was owned in the year 1830

by Captain James McIlhenny, of an honored and respected family on the Cape Fear. Captain McIlhenny was the victim of a well-known joke which gave the place its peculiar name. An extraordinary trade demand for goose-feathers at high prices led him to purchase in the up country a flock of geese which he intended to use for breeding purposes. He counted the increase before it was hatched, and anticipated with satisfaction large profits from the sale of feathers. The Captain selected the geese in person, and as he wanted white feathers, was careful to accept only the white birds. After waiting an intolerable time for the laying season to begin, he consulted a goose expert, and was informed, to his amazement, that his geese were all ganders.

Sedgeley Abbey.NEAR Gander Hall are the ruins of “Sedgeley Abbey,” which was the grandest colonial residence of the Cape Fear. It was of about the dimensions and appearance of the Governor Dudley mansion in Wilmington, and was erected about 170 years ago by an English gentleman of wealth and refinement, named Maxwell, who owned all the land as far as Smith's Island. The house was

built of coquina, a rock made up of fragments of marine shells slightly consolidated by natural pressure and infiltrated calcareous matter, of which there are still large formations there. The cellar alone remains, having been cut out of the solid rock. The South wing of the building was standing until about 25 years ago, when it was demolished and the material burned for fertilizers by an unsentimental tenant, who might have gathered all the oyster-shells he desired which had been left by the Indians at a slightly greater distance. A beautiful avenue of oaks extended from the mansion on the East for 1,500 feet towards the ocean in full view, and a corduroy road, which may still be seen, was built through a bay and lined with trees to the river landing. Some weird traditions about the house and its lonely master have come down through the neighborhood negroes, who still regard the place with superstitious awe. It is said that several attempts were made many years ago to find some gold alleged to be buried there, and although the times chosen were on bright, clear days, the sky became suddenly overcast, the wind moaned through the roofless walls, and cries and groans were distinctly heard by the treasure-hunters, who did not tarry for further investigation.

First White Settlement.

A FEW miles below this interesting ruin may yet be seen indications of the first white settlement on the Cape Fear in 1661 by the enterprising New Englanders from Massachusetts, who might have prospered, but their greed led them to destruction. For a time they carried on a profitable and apparently peaceable intercourse with the native Indians, but when they sent Indian children North to be sold into slavery under the pretense of instructing them in learning and in the principles of the Christian religion, the red men were not slow to discern their treachery, and from that time, as Lawson says, “they never gave over till they had entirely rid themselves of the English by their bows and arrows.”

The New Englanders left much cattle behind them, which the Barbadians four years later found in the possession of the Indians along the Cape Fear.

On this first attempt at a settlement on the Cape Fear river, Bryant, in his “Popular History of the United States,” page 272, says: “There were probably few bays or rivers along the coast, from the Bay of Fundy to Florida, unexplored by the New Englanders where there was any promise of profitable trade with the Indians. The colonist followed the trader wherever

unclaimed lands were open to occupation. These energetic pioneers explored the sounds and rivers South of Virginia in pursuit of Indian traffic, contrasted the salubrity of the climate and the fertility of the soil with that region of rocks where they had made their homes, and where winter reigns for more than half the year. In 1660 or 1661, a company of these men purchased of the natives and settled upon a tract of land at the mouth of the Cape Fear river. Their first purpose was apparently the raising of stock, as the country seemed peculiarly fitted to grazing, and they brought a number of neat cattle and swine to be allowed to feed at large under the care of herdsmen. But they aimed at something more than this nomadic occupation, and a company was formed, in which a number of adventurers in London were enlisted, to found a permanent colony. Discouraged, however, either by the want of immediate success, or for want of time to carry out their plans, or for some less creditable reason, the settlement was soon abandoned.”

Cape Fear Indians.

IT IS an interesting fact that the descendants of these Indians live in the same locality to the present day, and illustrate an unusual condition—an amalgamation of white, black and Indian races. The Indian characteristics, however, predominate. The men are thrifty, industrious and peaceable; engaged principally in fishing during the shad season, and in cattle-raising upon the same range that was occupied two hundred years ago by their savage ancestors.

Large mounds of oyster-shells, many pieces of broken wicker pottery, arrow-heads, and other relics of the red men are still found on the peninsula below Carolina Beach. During the late war these remains of an Indian settlement were frequently unearthed by the Confederates engaged upon the intrenchments around Fort Fisher; and here are buried the last of the Corees, Cheraws and other small tribes occupying the land once inhabited by the powerful Hatteras Indians. They were allies of the Tuscaroras in 1711, and in an attack upon the English suffered defeat, and have now disappeared from the earth and their dialect is also forgotten. The Hatteras tribe numbered about 3,000 warriors when Raleigh's expedition landed on Roanoke Island in 1584, and when

the English made permanent settlements in that vicinity eighty years later, they were reduced to about fifteen bowmen. The Cape Fear Coree Indians told the English settlers of the Yeamans colony in 1669 that their lost kindred of the Roanoke colony, including Virginia Dare, the first white child born in America, had been adopted by the once powerful Hatteras tribe and had become amalgamated with the children of the wilderness. It is believed that the Croatans of this vicinity are descendants of that race.

The Massachusetts settlers referred to the Cape Fear as the Charles river, which was applied, as was also the original name, Carolina, in honor of King Charles IX., of France, during whose reign Admiral Coligny made some settlements of French Huguenots on the Florida coast, and built a fort which he called Charles Fort, on what is now the South Carolina coast.

Lilliput.NEARLY opposite, surrounded by noble oaks, are the ancient estates of Lilliput and Kendal.

The first record extant of Lilliput plantation is in a patent from the Lords Proprietors, 6th November, 1725, recorded in the Secretary's office of North Carolina, to

Eleazar Allen. Mr. Allen was born at or near Charleston about 1692. He married Sarah, eldest daughter of Colonel William Rhett, about the year 1722. In 1730 he was recommended for one of the council of North Carolina by Governor Burrington, and appointed to that office by the Crown; but he does not appear to have assumed the duties until the 22d of November, 1735. He was appointed in that year with Nathaniel Rice, Roger Moore and Capt. James Innes, a Commissioner to fix the boundary line between North and South Carolina. He was made Receiver General of the Province of North Carolina from 1735 to 1748. During that time he experienced, in common with all the other public treasurers, great difficulty in collecting the quit rents due the Crown, for which he was held personally responsible by the British Government, and for the security of which he ultimately pledged his entire estate, including Lilliput.

An English gentleman who visited the Cape Fear in 1734 with thirteen other travellers, made special mention of Mr. Allen's residence, a beautiful brick house on Lilliput, adjoining Kendal, and also of his well-known hospitality. He says Mr. Allen was then speaker to the Commons, House of Assembly in the Province of South Carolina. Mr. Allen must have lived sumptuously and

entertained lavishly, as among the items of personal property in his estate made known at his death, was twelve dozen cut-glass table basins, now known as finger-bowls.

On the death of Mr. Allen, 17th January, 1749, aged fifty-seven years, at Lilliput, where he was buried, this plantation became the property and residence for a time of Sir Thomas Frankland. It was subsequently sold to John Davis, Jr., in 1765.

Sir Thomas Frankland was a grandson of Frances, daughter of Oliver Cromwell, who, upon the death of his brother, Sir Charles Frankland, in 1765, succeeded him as baronet. Sir Thomas was previous to that time an Admiral of the White in the British Navy, a post of great distinction. He married Susan, daughter of William Rhett, Jr., of Charleston. They have numerous descendants now living in England.

We find that, in 1789, Lilliput was in possession of the well-known McRee family of this section, and here was born the distinguished medical practitioner and diagnostician, Dr. James Fergus McRee, who afterwards lived and died in Wilmington.

Kendal.

THE adjoining plantation of Kendal was originally owned by “King” Roger Moore, who bequeathed it 7th March, 1747, to his son, George Moore. “King” Roger also devised to other heirs two hundred and fifty negro slaves.

George Moore, of Moore Fields, as he was afterwards called, was remarkable for his great energy, good management and considerable wealth. The original proprietors of the Cape Fear plantations were men of extraordinary discernment and discretion. They first took up all the best land within easy access, laid out and built their plantation residence, and then provided themselves with a comfortable summer house on the Sound. Evidences of this method are still to be seen in the many Sound roads which converge into the old thoroughfare at the east landing of the Brunswick ferry near Big Sugar Loaf and opposite the site of old Brunswick. George Moore's summer place was a tract on the north side of the creek at Masonboro, now owned by the McKoy family. He was twice married, and his wives, with remarkable fidelity and amazing fortitude, presented him every Spring with a new baby, until the number reached twenty-eight. An interesting relic of

this extraordinary family is preserved by Mr. Junius Davis. It is a book of Common Prayer, on the fly-leaf of which is inscribed the names and dates of birth of the entire family of twenty-eight children.

In common with the titled class in England, the Cape Fear planters held trade and trades-people in abhorrence, and kept themselves aloof from the commercial centres. They preferred to live on their plantations, and their social life betrayed a class distinction not at all in keeping with the democratic ideas of their descendants. In one respect, however, they greatly differed from the aristocracy of the Old Country—a generous and refined hospitality being universal and proverbial, and this excellent trait is still a striking characteristic of their successors on the river to the present day.

For personal reasons, to avoid the public parade of his numerous family through the town of Wilmington, it suited George Moore to cut a private road for his own use, from his plantation on Rocky Point to Masonboro Sound, by which his faithful wife and her remarkable progeny travelled on horseback in their yearly journeys from the country plantations to the seashore.

Mr. Moore's method of transporting his household effects was unique, by which he employed the services of a large retinue of negro slaves; upon the head of one

was placed a table; upon another a mattress; a third a chair, and so on, until fifty or more bearers were in line, when the cavalcade proceeded on foot towards Masonboro—an extraordinary and moving spectacle.

When corn was wanted at the summer place, one hundred negro fellows would be started, each with a bushel bag on his head. There is, said the late Dr. John H. Hill, quite a deep ditch leading from some large bay swamps lying to the west of the George Moore road. It used to be called the Devil's Ditch, and there was some mystery and idle tradition as to why and how the ditch was cut there. It was doubtless made to drain the water from those bays, to flood some lands cultivated in rice, which were too low to be drained for corn.

Kendal and Lilliput have been owned and cultivated for years past by Mr. Fred. Kidder, a type of the Old School gentleman, one of the most prominent and industrious planters on the river, a worthy and honored successor of the distinguished settlers on the Cape Fear, described as gentlemen of birth and education, bred in the refinement of polished society, and bringing with them ample fortunes, gentle manners and cultivated minds.

Orton.(Orton Plantation.)

AMONG the venerable relics of Colonial days in North Carolina there is probably none richer in legendary lore, nor more worthy of historic distinction, than the old Colonial plantation of Orton on the Cape Fear. The name is doubtless taken from the old town or village of Orton, near Kendal, in the beautiful lake district of England,

from whence the ancestors of the Moore family on the Yeamans side may have come to Barbadoes; the line of the Moore family being of Scotch Irish origin, as there is a Kendal Point and it is said an Orton plantation on that Island, which was the home of Sir John Yeamans, who afterwards settled upon the Cape Fear and was Governor of Clarendon.

Orton plantation was owned originally by Maurice Moore, the grandson of Governor Sir John Yeamans, and the son of Governor James Moore, of South Carolina, who came with his brother, Colonel James Moore, to suppress the Tuscarora Indian outbreaks in the Province of North Carolina in 1711. From him it passed to his brother, Roger Moore, known ever afterwards as “King” Roger. He was a man of lordly and distinguished bearing, and owned immense bodies of land in this part of the country, and was for many years a member of Governor Gabriel Johnston's Council. During his absence from home, in the early days of the settlement, his house at Orton was attacked, pillaged and burned by the Cree Indians, who lived on the Cape opposite the plantation. Some days afterwards “King” Roger, with a small force of neighbors and servants, seeing the Indians at play and bathing in the river near Big Sugar Loaf, marched up the river out of sight,

crossed over, and taking the savages by surprise, exterminated the whole tribe. His tomb, a brick mound, is still in a good state of preservation in the old family burying-ground at Orton. The spot, which has unfortunately in recent years been partly cleared, is described by the author of “Roanoke” as follows:

“I found myself in one of those spots which nature herself seems to have consecrated for her most holy rites. There was not a shrub, nor a blade of grass, within this sacred temple; there the garish beams of the sun never penetrate, but even at noonday a deep, solemn twilight reigns. The oaks, whose multitudinous branches form a thick canopy above us, looked as if they had witnessed the flight of centuries; and from their limbs and trunks there streamed hoary and luxuriant flakes of moss sweeping almost to the ground, and looking like elfin locks whitened by the frosts of a thousand years. Within this druid temple there are old brick vaults, without a name and without a date; and here, because, perhaps, nature herself seems to have formed a cemetery for her favorite child—here, beneath one of these vaults and close by the banks of the old Cape Fear, are supposed to repose the ashes of Utopia. The scene and the recollections which it awakened threw me into a meditative mood, and seating myself on one of the vaults, and looking out on the broad but lovely expanse of waters before me, I remained, listening to the subdued murmur of the distant ocean.”

This fine property was sold about the year 1860, with the slaves upon it, for one hundred thousand dollars; but the purchase money was never paid, and the estate deteriorated for more than fifteen years from inattention and decay. In 1876, a young English gentleman of education and refinement, named Currer Richardson

Roundel (a nephew of Sir Roundel Palmer who afterwards became Lord Chancellor of Great Britain as Lord Selborne), came to Wilmington evidently suffering with some mental disorder. He was induced by the agents to buy Orton, which had been in the market for some time previous, and he undertook to reclaim it, but met with difficulties which he had not anticipated, and which so depressed him that he took his own life. The writer found him early on the morning of July 26th, 1876, in his room at the hotel in Wilmington stripped to the waist, and lying upon the floor in a pool of blood, the deadly pistol in one hand, the other hand pointing to a ragged hole in his forehead. He was dead. He was buried by kind and gentle hands in Oakdale near Wilmington.

The present beautiful residence, with its majestic columns and its white and glittering vestments, now occupied by Colonel K. M. Murchison, the proprietor, was built about the year 1725 by “King” Roger Moore, of brick brought from England, and was afterwards enlarged and improved by the late Dr. Fred. J. Hill, a rice-planter, an intelligent gentleman, and a princely citizen, who was noted far and near for his elegant and refined hospitality.

Colonel Murchison has brought the plantation up to its best production—about a hundred laborers are

employed and many expensive permanent improvements have been adopted. He resides here with his family during the winter months, his home and principal business being in New York City.

These ten thousand acres include a fine game preserve, which is greatly enjoyed by the Colonel and his friends, to whom the pleasures of the chase are its principal attraction.

Born and reared on the upper Cape Fear of Scotch ancestors whose brain and brawn have ever infused new life and vigor throughout the business world, Colonel K. M. Murchison is honored; for out of nothing but a stout heart, an honest purpose and a good name, he has built up a fortune and achieved a reputation for integrity and usefulness among men who only acknowledge such as leaders.

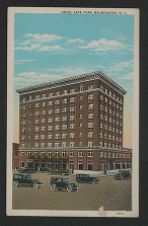

He deserves well of Wilmington because he has given liberally of his means for the development of our trade and industries. When there was not a hotel in the place worthy of the name, and when it was said that this lack barred a class of visitors hitherto unknown, but greatly to be desired by the community, he came forward and fearlessly invested a large amount in a first-class hotel, of which we should all be proud, although it has not been properly appreciated. Were our citizens animated with a little of the public spirit of their forefathers, who gave

three hundred and fifty thousand dollars to build and equip a Wilmington railroad, when the entire taxables were only three hundred thousand dollars, “The Orton” would always be filled to overflowing and such an enterprise receive its just reward.

Colonel Murchison served throughout the war as Colonel of the 54th N. C. Troops, took part in the active Virginia campaigns, and upon the conclusion of peace returned to New York, where he has ever since been engaged in business.

Colonial Governor Tryon's Palace—Scene of the First Outbreak of the

Revolutionary War.

(Colonial Governor's Palace.)

ABOUT half a mile to the South of Orton House, and within the boundary of the plantation, are the ruins of Governor Tryon's residence, memorable in the history of the United States as the spot upon which the first overt act of violence occurred in the war of American Independence, and nearly eight years before the Boston

Tea incident, of which so much has been made in Northern history; while this Colonial ruin, the veritable cradle of American liberty, is probably unknown to nine-tenths of the people on the Cape Fear at the present day.

This place, which has been eloquently referred to by two of the most distinguished sons of the Cape Fear, and direct descendants of Sir John Yeamans, the late Hon. George Davis and the Hon. A. M. Waddell, and which was known as Russelborough, was bought from William Moore, son and successor of “King” Roger, by Captain John Russell, Commander of His Britannic Majesty's sloop of war “Scorpion,” who gave the tract of about fifty-five acres his own name. It subsequently passed into the possession of his widow, who made a deed of trust, and the property ultimately again became a part of Orton plantation. It was sold March 31st, 1758, by the executors of the estate of William Moore to the British Governor and Commander-in-Chief, Arthur Dobbs, who occupied it and who sold it or gave it to his son, Edward Bryce Dobbs, Captain in His Majesty's 7th Regiment of Foot or Royal Fusileers, who conveyed it by deed dated February 12th, 1767, to His Excellency William Tryon, Governor, etc. It appears, however, that Governor Tryon occupied this residence prior to the date of this deed, as is shown by the following official

correspondence in 1766 with reference to the uprising of the Cape Fear people in opposition to the Stamp Act:

“BRUNSWICK, 19th FEBRUARY, 1766,

“ELEVEN AT NIGHT,

“SIR:—

“Between the hours of six and seven o'clock this evening, Mr. Geo. Moore and Mr. Cornelius Harnett waited on me at my house, and delivered to me a letter signed by three gentlemen. The inclosed is a copy of the original. I told Mr. Moore and Mr. Harnett that as I had no fears or apprehensions for my person or property, I wanted no guard, therefore desired the gentlemen might not come to give their protection where it was not necessary or required, and that I would send the gentlemen an answer in writing to-morrow morning. Mr. Moore and Mr. Harnett might stay about five or six minutes in my house. Instantly after their leaving me, I found my house surrounded with armed men to the number I estimate at one hundred and fifty. I had some altercation with some of the gentlemen, who informed me their business was to see Capt. Lobb, whom they were informed was at my house; Captain Paine then desired me to give my word and honor whether Captain Lobb was in my house or not. I positively refused to make any such declaration, but as they had force in their hands I said they might break open my locks and force my doors. This, they declared, they had no intention of doing; just after this and other discourse, they got intelligence that Captain Lobb was not in my house. The majority of the men in arms then went to the town of Brunswick, and left a number of men to watch the avenues of my house, therefore think it doubtful if I can get this letter safely conveyed. I esteem it my duty, sir, to inform you, as Fort Johnston has but one officer, and five men in garrison, the Fort will stand in need of all the assistance the “Viper” and “Diligence” sloops can give the commanding officer there, should any insult be offered to his Majesty's fort or stores, in which case it is my duty to request of you to repel force with force, and take on board his Majesty's sloops so much of

his Majesty's ordnance, stores and ammunition, out of the said fort as you shall think necessary for the benefit of the service.

“I am, sir, your most humble servant,

(Signed)

“WM. TRYON.”

“To the Commanding Officer, either of the Viper or Diligence Sloops of War.”

The writer, who frequently enjoys the old-time hospitality of Orton, had often inquired for the precise location of the ruins of Governor Tryon's Russelborough residence, without success. But during a recent visit, and acting upon Colonel Waddell's reference to its site on the north of old Brunswick, the service of an aged negro who had lived continuously on the plantation for over seventy years was engaged, who, being questioned, could not remember ever having heard the name Russelborough, nor of Governor Dobbs, nor of Governor Tryon, nor of an avenue of trees in the locality described. He said he remembered, however, hearing when he was a boy about a man named “Governor Palace,” who had lived in a great house between Orton and old Brunswick.

We proceeded at once to the spot, which is approached through an old field, still known as the Old Palace Field, on the other side of which, on a bluff facing the east, and affording a fine view of the river, we found hidden in a dense undergrowth of timber the foundation walls of Tryon's residence. The aged guide showed us the

well-worn carriage road of the Governor, and also his private path through the old garden to the river landing, a short distance below, on the south of which is a beautiful cove of white and shining sand, known, he said, in olden times, as the Governor's Cove. The stone foundation walls of the house are about two feet above the surface of the ground. Some sixty years ago the walls stood about twelve to fifteen feet high, but the material was unfortunately used by one of the proprietors for building purposes.

The old servant pointed out a large pine tree near by, upon which he said had been carved in Colonial times the names of two distinguished persons buried beneath it, and which in his youthful days was regarded with much curiosity by visitors. The rude inscription has unhappily become almost obliterated by several growths of bark, and the strange, mysterious record is forever hidden by the hand of time.

A careful excavation of this ruin would doubtless reveal some interesting and possibly valuable relics of Governor Tryon's household. Near the surface was found, while these lines were being written, some fragments of blue Dutch tiling, doubtless a part of the interior decorations; also a number of peculiarly shaped bottles for the favorite sack of those days, which Falstaff called Sherris sack, of Xeres vintage, now known as dry sherry.

Ruins of Brunswick.

ABOUT a quarter of a mile distant towards the South, and yet within the limits of this time-honored estate of Orton, are the ruins of the old Colonial town of Brunswick, once the chief seaport and seat of government of the Province of North Carolina. Its public buildings and substantial houses have long ago crumbled to their foundations, which still remain.

The daily hum of traffic has long since ceased, and the busy feet that trod its now silent streets have mouldered into dust.

“No more for them the blazing hearth shall burn,Nor busy housewife ply her evening care,Nor children run to greet their sire's return,Or climb his knee the envied kiss to share.”The glad voices of the village children, the merry ring of the blacksmith's anvil and the hearty yo-ho of the sailors in the bay have melted away into the silence of the dead, which is only broken by the hooting owl and the barking fox, or by the plaintive cry of the whippoorwill and the plunge of the osprey in the now peaceful waters of the Governor's Cove, while from across the narrow isthmus is heard the moaning of the lonely sea.

Ruins of St. Philip's Church.WITHIN the boundaries of this forgotten town are the picturesque ruins of St. Philip's Church, which was built by the citizens of Brunswick and principally by the landed gentry about the year 1740. In the year 1751 Mr. Lewis Henry DeRosset, a member of Governor Gabriel Johnston's Council and subsequently an expatriated Royalist, introduced a bill appropriating to the church of St. Philip at Brunswick and to St. James’ Church at Wilmington, equally, a fund that was realized by the capture and destruction of a pirate vessel, which, with a squadron of Spanish privateers, had entered the river and plundered the plantations. A picture (“ECCE HOMO”), captured from this pirate, is still preserved in the vestry-room of St. James’ Church in Wilmington.

St. Philip's Church was built of large brick brought from England. Its walls are nearly three feet thick and are solid and almost intact still, the roof and the floor only having disappeared. Its dimensions are nearly as large as those of our modern churches, being 76 feet 6 inches long, 53 feet 3 inches wide, standing walls 24 feet 4 inches high. There are 11 windows, measuring 15×7 feet, and 3 large doors. It must have possessed

much architectural beauty and massive grandeur with its high pitched roof, its lofty doors and beautiful chancel windows.

Upon the fall of Fort Fisher, which is a few miles to the southeast of Orton, in 1865, the Federal troops visited the ruins of St. Philip's, and with pick-axes dug out the corner-stone, which had remained undisturbed for one hundred and twenty-five years, and which doubtless contained papers of great interest and value to our people. It is a singular fact that during the terrific bombardment of Fort Anderson, which was erected on Orton, and which enclosed with earthworks the ruins of St. Philip's, while many of the tombs in the church-yard were shattered and broken to pieces by the storm of shot and shell, the walls escaped destruction; as if the Power Above had shielded from annihilation the building which had been dedicated to His service.

This sanctuary has long been a neglected ruin, trees of a larger growth than the surrounding forest have grown up within its roofless walls, and where long years ago the earnest prayer and song of praise ascended up on high, a solemn stillness reigns, unbroken save by the distant murmur of the sea, which ever sings a requiem to the buried past.

In concluding his most interesting sketch of old

Brunswick, in “A Colonial Officer and His Times,” the graceful and gifted author, Colonel Alfred Moore Waddell, says:

“Memorable for some of the most dramatic scenes in the early history of North Carolina as the region around Brunswick was (being the theatre of the first open armed resistance to the Stamp Act, and not far from the spot where the first victory of the Revolution crowned the American arms at Moore's Creek Bridge, on the 27th of February, 1776), its historic interest was perpetuated when, nearly a century afterwards, its tall pines trembled and its sand-hills shook to the thunder of the most terrific artillery fire that has ever occurred since the invention of gun-powder, when Fort Fisher was captured in 1865. Since then it has again relapsed into its former state, and the bastions and traverses and parapets of the whilom Fort Anderson are now clad in the same exuberant robe of green with which generous nature in that clime covers every neglected spot. And so the old and the new ruin stand side by side in mute attestation of the utter emptiness of all human ambition; while the Atlantic breeze sings gently amid the sighing pines, and the vines cling more closely to the old church wall, and the lizard basks himself where the sunlight falls on a forgotten grave.”

Colonial Ferry and Inn.THE ruins of an inn and ferry-house attract attention at old Brunswick landing. This ferry to the landing at Big Sugar Loaf on the opposite side of the river, a distance of over two miles, must have been an exposed and dangerous passage during stormy weather. It was

kept by Cornelius Harnett and connected with the only road to the northern part of the Province. This Colonial road is still used at the present day, and may be seen at the old landing place near Big Sugar Loaf.