JOHN VYTALA TALE OF THE LOST COLONY

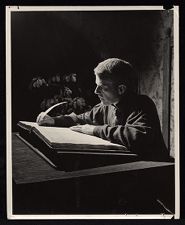

Illustration of John Vytal

WILLIAM FARQUHAR PAYSON

John Vytal

John VytalA Tale ofThe Lost ColonyBYWILLIAM FARQUHAR PAYSONWilliam BriggsToronto

Copyright 1901, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

“He was one of a lean body and visage, as if his eager soul, biting for anger at the clog of his body, desired to fret a passage through it.”

Thomas Fuller

Foreword

No epoch in American history is more essentially romantic than that in which, for a few years, less than one hundred colonists from England lived on the island of Roanoke, off the coast of old Virginia. Nevertheless, although the history of our continent, from the landing of Columbus to the end of the Spanish-American war, has been exhaustively exploited in fiction, the pages dated 1587-1598 seem to have been left unturned. Yet the life of the Roanoke colony contained not only adventure, hazard, and privation in a far greater degree than the maturer settlements of later years, but also an underlying emblematical element, and in its end an insoluble riddle. In being thus both mystical and mysterious, it paramountly inspires romance.

The mystery has filled many pages of history, but always as an enigma without solution. The fate of the colony is utterly unknown, historians of necessity relegating it to the limbo of oblivion.

Bancroft, for one, concludes his account of the colonization thus:

“The conjecture has been hazarded [by Lawson and others] that the deserted colony, neglected by their own countrymen, were hospitably adopted into the tribe of Hatteras Indians, and became amalgamated with the sons of the forest. This was the tradition of the natives at a later day, and was thought to be confirmed by the physical character of the tribe in which the English and the Indian race seemed to have been blended. Raleigh

long cherished the hope of discovering some vestiges of their existence, and, though he had abandoned the design of colonizing Virginia, he yet sent, at his own charge, and, it is said, at five several times, to search for his liege-men. But it was all in vain; imagination received no help in its attempts to trace the fate of the colony of Roanoke.”

Opposing this view, many authorities believe that a massacre occurred by which many of the English suffered at the hands of hostile savages. In the ensuing story, however, I have ventured to explain the oblivion of the colony's end in a way which I believe has not yet been suggested.

After this preamble I hasten to assure the reader—perhaps already surfeited with historical novels—that he shall find scarce more of history in the whole tale following than in the foreword just concluded. The “manners and customs” also are rigidly suppressed. I have made bold, though, to use several of the colonists’ names which have been preserved, but the conception of character is my own.

W. F. P.

Book IJohn Vytal A Tale of the Lost Colony

CHAPTER I“. . . framed of finer mould than common men.”

—Marlowe, in The Jew of Malta.

It is not to yesterday that we would take you now, but to a day before innumerable yesterdays, across the dead sea of Time to a haven mutable yet immortal. For the Elizabethan era is essentially of the quick, although its dead have lain entombed for centuries. The world of that renascent period, alight with the spontaneous fire of intellectual and passionate life, shines through the space of ages as though then, for the first time, it had been cast off from a pregnant sun.

Overcoming the remoteness of the epoch by an appreciation of this vivid reality, we pause at the outset near the great south gate of London Bridge as it stood three centuries ago.

On a certain April afternoon the massive stones and harsh outlines served to heighten by contrast the effect of lithe grace and nonchalance apparent in the figure of a young man, who, leaning lightly against the barbacan, presented a memorable

picture of idleness and ease. Yet a fleeting expression in the youthful face belied the indolence of attitude. For in more ways than one “Kind Kyt Marlowe” resembled the spring-tide, whose tokens of approach he intuitively recognized. His eyes, usually soft and slumberous with the light of dreams, now and again shone brilliant like black diamonds. With all his careless incontinence, he possessed a latent power, a deep, indeterminable force, portending broad hot days and nights of storm.

His face, mobile dark and passionate, showed an almost alarming intensity. His brow, lofty but not massive, was surmounted by silken hair so black as to appear almost purple in the sunlight. He wore no beard, a small mustache adding to the refinement of his features, save for the fulness of his lips, which it could not hide. Taken as a whole, his face was the face of a man who had no common destiny; of a man who would drain the cup and leave no dregs, be the draught life-elixir or poison; of a man, in short, who might all but transcend his humanity by the fulness of life within him, or be suffocated and overwhelmed by the very superabundance of that life. For there are some seeming to be born with a double share of vitality, a portion far greater than was meant for man; and when this vitality, maturing, begins its re-creation, threatening all feebler forms with a new revolutionary condition, then the error is apparently discovered and the entire share of life recalled.

Christopher Marlowe was one of these men, but as he leaned against the Southwark Gate, that afternoon in early life, looking up the High Street through the gathering dusk, his eyes showed little more than the cheerful glow of a wood-fire, the mere hint of an unrestrainable flame underlying their expression.

Soon, however, the poet's reverie was broken. The afternoon's bear-baiting being over, and Southwark's amphitheatre empty of its throngs, a number of the earliest to leave were now upon the High Street, known then as Long Southwark. Seeing them approaching him on their way to London, Marlowe turned and walked in the same direction.

At the sign of “The Three Bibles” books and broadsides were for sale. It was this small, antiquated den on London Bridge that the author sought with the unconscious step of one who follows a familiar way.

He had but just entered the low-studded, gloomy shop, and greeted Paul Merfin, its owner, when the scabbard of a sword clanked on the threshold, and a man of great stature, accoutred as a soldier, darkened the doorway. With no prelude of salutation, the new-comer demanded of Merfin, in a voice of anxiety, “Tell me, hast seen—?” Then for the first time he became aware of Marlowe's presence, and, lowering his heavy tones to a whisper, finished his query in the bookseller's ear.

“Nay,” was Merfin's answer, “I have seen nothing of him.”

The soldier's face grew yet more uneasy. “Ill fortune!” he exclaimed; “it is always so,” and he would have left the shop had not Marlowe detained him.

“Stay,” said the poet, “I could not but hear your question, for your whisper, sir, being no gentler than a March wind, nips the ear whether we will or no. So you, I take it, are that giant, Hugh Rouse, who follows the Wolf. Of you twain I have heard much, and wondered if the tales from the South were true that told of so great a courage. I have seen the man, show me now the master.”

“Would, sir, that I could, but I know not where the master is. And who, may I ask, are you, that show so deep an interest?”

“Not one to be feared,” returned Marlowe, smiling; “an idle poet who has sung of braver men than his eyes have yet beheld, and would see a man still braver than the song—Kyt Marlowe, at your service, good my Rouse,” and so saying, the poet, with a hand through the big soldier's arm, led the way from the shop out to the High Street of Southwark. “Had you not another comrade in the wars, a vagabond of most preposterous paunch and waddling legs? I have heard that he, too, follows milord, the Wolf.”

“There is such an one,” said Rouse, “but, alack! he also is missing. I pray you, though, call not our leader ‘Wolf’ again; none save fools and his enemies so name him.”

“But I have heard that he is ferocious as a wolf, lean and very gray. The sobriquet is not ill-fitting.”

“Nay,” said the soldier, “in truth it fits most aptly in description of his looks, for though he is but five-and-thirty, his head and beard are grizzled, that before were black as night.”

“’Tis not strange,” observed the poet, leading his new acquaintance toward a favorite hostelry; “campaigning in the South ages many a man before his time.”

“Ay, but that is not all.”

“What more, then?”

“It is briefly told,” answered the soldier. “His father was sent by her Majesty, our queen, with messages to Henry of Navarre, in whose army we two fought side by side. The envoy and his wife, who were passing through Paris—”

“What!” interrupted the poet, “were they his parents? I had forgot the story. It was the night

when Papists murdered Huguenots, the night of St. Bartholomew. An Englishman and his wife were slain ere their son, who had come from the South to warn them, could intervene. He saw his mother struck down, saw the sword and the bared breast in the glare of a dozen torches, and saw his father killed, too, after a brief struggle. Then the youth, who had cut his way nearer to the scene, found himself beset on all sides by a bristling thicket of steel that no man could divide. He fell. The Catholics laughed and left him for dead across the bodies of his parents. But the lad was not so easily undone. He rose, despite a wound beneath the heart, and, dripping blood, carried the two dead forms to the Seine, where, in the shadow of the Pont Neuf, he weighted his burdens with stones and buried them beyond the reach of desecration. The tale came to me as come so many legends of the wars from nameless narrators. That youth, then, is—”

“John Vytal,” concluded the soldier, gravely. “He had fought before then at Jarnac and Moncontour; but now he warred against the Catholics with redoubled fury. ’Twas through him, I tell you, came the victorious peace of Beaulieu and Bergerac, and the fall of Cahors.”

“Find me this man!” The words burst from the young poet in a voice of eager, impetuous command. “I must see him!”

“He was to have been at the ‘Tabard’ two hours since,” returned the soldier, despondently, “but came not.”

“Then let us return thither and wait for him a year, if need be. He will come at last, ’tis sure.”

The narrow way on the bridge near by was now choked with its evening throngs, and, as daylight began to fade, a babble of many tongues rose

and fell in the streets of Southwark, with which the creaking song of tavern signs, aswing in the evening breeze, blent an invitation to innumerable stragglers from the bear-fight.

“Eh, now,” said Rouse to one of these who joined him, “do you honor the ‘Spurre,’ Tom Watkins, or the ‘King's Head’?”

“Nay, neither, Hugh; they lack that mustiness and age which make the inn. For this there's none like the ‘Tabard,’ that being a most ancient hostel. D'ye know what ‘Tabard’ is?”

“Nay, poorly; some kind o’ garment, I've heard.”

“It is, Hugh; a jacket with no sleeves, slit down from the armpits and winged on the shoulders. Thou'lt see it on the tavern sign. Only the heralds wear the things to-day, and call ’em coats-of-arms in service. Now, d'ye see, it's meet that I, a breeches-maker, should mind me of other attire as well, and not go breast-bare about the town. So, Hugh Rouse, I make my breeches by day, and I put on my tabard by night, thank the Lord, and I'm a well-arrayed coxcomb, ye'll allow. But here we are; get you in.”

The speaker, a thin fellow of middle age and height, laughed over this oft-repeated joke till his sallow face looked like a tangle of his own leathern thongs, showing all its premature wrinkles, and his bent shoulders shook convulsively; yet there was no sound in the laughter save a kind of whispered crackle like the tearing of stiff paper.

On entering the inn, Marlowe and the soldier sought an obscure corner, but Thomas Watkins, the breeches-maker, being a character of no small popularity among the worthies of the borough, and one who had the commiseration of many, for good and sufficient reasons, seeing the tap-room already well filled, remarked thereon to the host, after his usual

manner of forced joviality. “How now, have I allowed myself to be forestalled and beaten in our race from the gardens to your spigot?” He surveyed the tables, with their dice-boxes, cards, and foaming cups, feigning an astonished air. Several of the guests looked up at him, laughing, with a certain indulgent, almost pitying, amusement. Simon Groat, the tavern-keeper, smiled, too, in fat good-humor.

“ ’Tis not often so,” he returned; “you know the saying, Thomas, that the breeches you make yourself are unusual easy for quick running to the tavern, and uncommon broad and thick in the seat, that you may sit on our ale-bench by the hour with small wear to them.” The crowd laughed yet more heartily at this, though many had heard the same stock jest before. “But now, to tell truth, Tom, ye're the very first from the gardens.” He lowered his voice. “These be soldiers, as you see. Some arrived at Portsmouth from the Low Countries last month, and already must sally forth again, most madly, methinks, on the perilous Virginia voyage.”

The breeches-maker glanced about him for the first time with a close attention to the room's occupants. For the most part they were unknown to him, several wearing the unmistakable air of fighting men. But his scrutiny was suddenly interrupted by the entrance of others more familiar in appearance. Leading the new arrivals into the tap-room came a short, nervous man, very thin both of body and voice. As he saw Watkins, his face, which had been eager, showed disappointment. “Faugh!” he ejaculated, turning to Groat; “Tom's told you.”

The host looked as surprised as a very bland, corpulent person can. “Nay, Peter, what's he told me?”

The expression of Peter Sharp, needle-maker by trade, news-monger by preference, grew eager again.

“That's like Tom,” he declared. “Some observation concerning the ale-tap instead of a good story, I'll warrant.” He turned to his fellow-guests, with the exception of those who had entered behind him. “Were none of ye there,” he asked, “to see a most astounding bear-baiting?”

The soldiers looked up with interest from their games. Marlowe and Rouse in particular showed a keen attention to the speaker. “Alack!” whispered Rouse, “I knew he'd do it.” But his companion, all ears for what was coming, made a cautious gesture commanding silence, and said nothing.

“This is how it happened,” began the needle-maker, now sure of an attentive audience. “First, Old Sarcason—by Heaven, the gamest bear, as I thought, that ever entered ring!—came badly off. The wards must needs grab every dog's tail and pull it might and main to hold them back from killing him. But Harry Hunks gave better fight, and nearly hugged a mastiff pup to death. And Little Bess of Bromley, too—ye should have seen her punish Queen Elgifa, a noble slut in her day. I've rarely seen so great sport at public baiting; but Bruin and his wards were on their mettle. The French ambassador was there. At the end they had a new pastime in store for us. And here came the trouble. Leading a small brute—him they call King Lud—faith, little more than cub, but strong as iron and uncommon savage, being a son of Old Sarcason and Little Bess—out they come with him, and blind his eyes. Then, tying him fast to the post, they flog his hide, each with a leathern whip, till the blood runs.* Whereat down jumps from a seat near the ring a man we knew not, tall and

* Incredible as it may seem, this despicable deed of cruelty has been authentically recorded by writers of the time.travel-stained, and says that they should stop their ‘wanton sport.’ And following him into the ring jumps a clownish fellow of low stature and round paunch, like a stage jester in appearance. They both carried arms, the first a rapier, the mountebank a broadsword half his own length. We thought, then, it was all arranged, some new-conceived buffoonery to finish the baiting. Quick as can be, the two, with drawn swords, went forward and untied the bear, about whose back a lash still whistled. ‘Tie him up,’ says the tall man, pointing to one of the floggers. And suddenly ’twas done before we knew it. There stood Sir Knight of the Whip tied to the post in place of King Lud, and writhing most horribly, while the pot-bellied little clown danced about him, plying the self-same lash for dear life. In the mean time the other—of high station, I take it, despite his weatherworn grab—calmly unblinds the bear and turns him toward the sight at the whipping-post. The wards stood speechless, for Master Long-man held his rapier ready, and a pistol stuck out at his belt.”

The needle-maker paused for breath, and, having a certain dramatic instinct, called for a flagon of ale, in order to postpone his climax. The other inmates of the tavern now listened to the nervous little storyteller with keen interest and some excitement. The pair in a corner waited breathlessly for the end. From time to time as the narrative had proceeded the bigger of the two could scarcely suppress his agitation, but, being restrained by Marlowe, he managed to voice the alarm he felt by no more than some occasional smothered ejaculation, such as, “I knew he'd do it!” or, “In troth, he was ever thus!”

“But the most astonishing incident is yet to come,” resumed Peter Sharp, wiping the ale-foam from his lips. “No sooner did King Lud see what was going

forward than along he shambled slowly toward the clownish fellow, and, standing up on his hind legs, put a great paw on each of the little man's shoulders, and looked at him in a most friendly way as dogs do. Whereat the mountebank dropped his whip and spoke to his superior officer, as I took the other to be. Then Sir Soldier, drawing out a fat purse and turning to the Master of the Sports, who was even now coming into the ring in great dismay, nodded and delivered the purse into his hands. At that the stout retainer made a comical bow to all the people around the ring, as who should say, ‘I hope we have amused you,’ and, leading King Lud by his chain, calmly walked out of the arena. From this we felt all the more sure that it had been part of the performance. But I could not believe that the angry and amazed looks of him who had been flogged in Bruin's place, and of the wards, were feigned. Moreover, when the tall man left, he says to us all: ‘Call ye yourselves men and watch such sports as these? Get ye to your kennels with the other dogs.’ Whereupon he, too, walked from the ring slowly. It was all done with such despatch by him, and such a ready wit by his servant, that they befooled us utterly. Thinking it a comicality, no man in all the audience took action, and the few below us in the ring, being so terrified and bewildered by the sudden remonstrance and show of arms, stood dumfounded. But even then, I think, they might have regained their senses in time to send the twain to jail had not the Master of the Sports advised against pursuit, being, as I believe, well requited for King Lud and not unfamiliar with his purchaser.”

The needle-maker raised his cup and drank deep, while a buzz of conversation began about him. A look of unspeakable relief had come to the faces of the soldier and the poet in the corner.

Toward this pair the eyes of a group across the room were frequently directed. Among the latter company one figure was particularly noticeable, being that of a very young man, of medium size, bearing himself not ungracefully, and wearing a riding-cloak thrown off over one shoulder above an inconspicuous doublet of dark red satin, which, together with his silken hose and velvet, befeathered hat, revealed the civilian. The man nearest to him, many years his senior, was, by name, Sir Walter St. Magil; by profession, unmistakably a soldier. He, too, was of medium height and aristocratic carriage, though with a face rendered exceedingly ill-appearing by a cast in one of his eyes which drew the pupil so far in toward the nose as to leave but a half of it visible.

As the needle-maker concluded his tale this man smiled knowingly, and the smile had more of meaning in it than of mirth or pleasantness. “There is but one,” he said, that all might hear him—“but one with a brain so addled as to be capable of such folly. And that man, my masters, is none other than John—”

But the sentence died on his tongue, half spoken. For Hugh Rouse, who until now had taken no part in the general conversation, came forward from his corner like a great mastiff from its kennel.

“Nay, Sir Walter,” he objected, “I pray you make no mention of the man's name; it will do no good.”

For an instant the other's brow clouded, but, controlling himself with ease, he returned, suavely: “Oh, an you, as the man's friend, desire it, I keep silence. Ne'er-the-less, fool, I call him, name or no name, thus to interrupt a bear-baiting.”

Little satisfied with this forbearance, Hugh, whose honest face had been for the moment almost threatening,

reluctantly resumed his seat in the corner near Marlowe. “Ah, Hugh Rouse,” observed the latter, in an undertone, “your name neatly fits its owner. But you did well.”

In the mean time, Sir Walter St. Magil, whose remarks had been so unceremoniously interrupted by Rouse, was talking in a low voice with his young companion. “The man,” he said, so low that none but the immediate listener could hear him, “is Vytal—John Vytal. We've fought together in the Low Countries, but—” and here his voice sank to a whisper, while he glanced furtively about him, “he's not one of our men.”

“Nay, I supposed not,” rejoined the young man, in a careless voice, contrasting strongly with his elder's caution; “therefore, why consult this fellow's pleasure?”

“Because we might but stir up mischief by opposing the brawling giant. Well I know him, for he is Vytal's follower. As I live, the man has but few friends, yet those few would die for him.”

“Some day the opportunity may be theirs,” observed the other, smiling almost boyishly.

“Yes,” assented St. Magil, in a grimmer tone, “but now we must have patience. For the moment let us guard Vytal's name as carefully as we conceal your own. Which reminds me—I'd almost forgot—what name dost go by now?”

“’Tis ‘Frazer’; but give heed! That tale of bear-flogging has set these louts at odds.”

He spoke truth, for Peter Sharp, the needle-maker, now not over-steady, thanks to the never-idle tapster, was indulging in an argument with Watkins, the breeches-maker, concerning his favorite entertainment. Entering with them into the discussion, though with less volubility and heat, were Samuel Gorm, a

bear-ward, and Alleyn, a young actor of plays and interludes. It was not, however, until Peter expressed the astonishing opinion that “none save a fool would enter a play-house, whereas, every man worthy of the name was at one time or another to be seen in the Paris Gardens,” that Hugh Rouse rushed into the argument in his customary reckless manner.

“Hast been,” he asked, vehemently, “to the ‘Curten’ and seen Master Alleyn, here, go through his acting? ’Sdein! The smell of powder, the sight of a musketoon, the glisten of pikes—and what not?—oh, they befool me finely!” The soldier turned to Marlowe, his broad face red with enthusiasm to the roots of his flaxen hair. “It befools me finely,” he repeated. “I remember real rage and blows. Hand goes to hilt instinctively. Now, in this new invention writ by you, Master Marlowe, there is good cause for excitation.” He paused, and, draining his cup, glanced at the actor. “I’ faith, Alleyn, when you trod on Bajazeth's neck to mount his throne, I stood there, too. When you caged the caitiff, I baited him betwixt the bars. When ye fought with him, I cried, ‘Couragio! Bravo! Tamburlaine! Well thrust!’ and when you conquered, ‘Thank God!’ says I, ‘’twas most brave work. There's no blade in Spain or England can send a knave so quick to hell.’ And that was but a play called ‘Tamburlaine,’ Master Alleyn, all conceived by Marlowe and thee—a pen and a sword together.”

Hearing Rouse thus expatiate on the wonders of the drama, the youthful civilian, then known as Frazer, seemed to catch the somewhat turbulent manner of the soldier, and retorted with a sneer of mingled patronage and amusement: “Ay, my good Pike-trailer, you may be thus easily gulled, being of so hot a nature, but we, the less fiery, see through the play-actor's

pretensions.” To this Rouse made no response, having, in truth, an unready wit, and a tongue that, as he occasionally realized, was quick enough to embroil him in controversy, but slow to rescue him there-from with the preservation of an honorable peace. Marlowe, on the other hand, was naturally far less clumsy in wordy wars, and stood willing to espouse his new friend's cause in an argument which he, as playwright, was so well fitted to maintain.

“How now,” said he to Frazer, “would not a soldier be the first to cry out against mere mimicry of that he holds most noble?”

“Indeed, Master Poet,” returned Frazer, with an expression less haughty, but none the less amused, as he turned to his new opponent, “I know not, being unfamiliar with men-at-arms; yet I still maintain that the contest being real, as in a bear-fight, the excitement to the majority is greater. The play is but an imitation, and many actors, with all deference to you, Master Alleyn, no more than strutting mimics. I've seen stage kings, upon their exits from the innyards of their mighty conquests, go home as shambling hovellers. I've seen mock heroes, who erst-while have trailed their pikes and rung their rowels to the tune of Spanish oaths, go white as death at sight of poniard drawn in earnest. But bear-baiting is real. The bear's a bear, the dog a dog. They know none other rôle than this—to fight to kill, and not for plaudits. Roar, growl, slobber, grasp of shaggy arms, clinch of naked teeth—by all the gods, these things are real! Here, Jack Tapster, another flagon to the bear!”

For a moment there was silence following the outburst of enthusiasm. This young Frazer had not a little dash of the reckless, roystering sort, causing the audience to forget his sinister companion, looking

on askance with that eye which lay half behind his nose as though in an effort to hide itself from those who might be capable of reading its real expression. The tap-room's occupants were strongly influenced by what they deemed an eloquent description of their favorite sport. But Marlowe was one of the few who saw deeper.

“Even so,” said he, with a sudden outburst of young conceit. “There's more than battle in my ‘Tamburlaine.’ There's love, parentage, death in the play. Each day I feel most miserable when Zenocrate expires. A bear dies—that is but the death of a bear. Zenocrate's death is a queen's demise—a scene—a picture—call it what you will—’tis art, and in bear-baiting, I tell you, there is no art.”

“Ay, Marlowe,” observed Rouse, “excellent well said. I cannot find words as thou canst.”

“Art!” exclaimed Frazer, “art! Is that a paint-brush in thy dainty scabbard, Sir Poet?” And again he laughed with a curiously boyish merriment.

“Ay,” returned Marlowe, “and its crimson color grows dim. The paint-brush would fain find a palette to mix on and daub afresh, Master Princox.”

“A palate!” ejaculated Frazer, laughing with genuine mirth; “that sheath must hold an axe then. It's by the palate wine goes to the stomach, and an axe, so I've heard, to the block.”

“Ha, but thy wit,” rejoined Marlowe, “ ‘wol out,’ as Geoffrey Chaucer said. Nay, though, perhaps it is because you watch fearfully the doings near block and gallows that you know so well their manners. Wit—foh! It is easy to play the game of words as Tarlton does. I call it but juggling phrases, and robbing language of its meaning, as a vagabond juggles stolen coin.”

“Ay, juggles phrases,” echoed Rouse, with admiration.

“But we'll see a nobler conjury,” pursued Marlowe, upon whose hot blood the insolent bearing of Frazer was having its effect. “The artist's brush shall paint the juggler's tongue a deeper red—the—” The poet's threat, however, uttered while he rose and drew his sword, was interrupted by Simon Groat, the host, who came forward with hands uplifted in expostulation.

“Gogsnouns!” he exclaimed. “Not so, my worshipful guests. Take ye the ‘Tabard’ for a tilt-yard? Nay, nay—I pray you—here, tapster, a quietus for all—open the ale-tap wide. Free flagons, gentles, an it please you to wait and drain them. You'll find more space without—down by the bridge-house there is room for—”

And now Sir Walter St. Magil, the apparent adviser of young Frazer, lent his aid to Simon Groat in calming the turbulent disputants. “Ay, Master Frazer,” said he, “respect thine host—the quarrel's idle, gentlemen, if you'll permit me.”

“But the swords,” declared Marlowe, “shall not be.”

“Nay,” cried Frazer, in whose veins the Canary wine ran riotous. “Your artist's brush would fain paint—”

“Fool!” roared Rouse, “you'll pay high for the picture,” and so saying the big fellow pushed aside tables and chairs, while Marlowe stood on guard with rapier drawn. But at this instant, in a window behind Frazer, yet plainly visible to Rouse and Marlowe, the face of a man appeared.

“Fools all!” he said, in a voice that clipped words and shot them from him like bullets. “Sots! Ye're the bears! Why this babble of plays, when you only

enact a bear-baiting yourselves, and that poorly? ’Twere nobler to be a bear or bull-dog than an ass.” Whereat, as suddenly as it had come, the face of the speaker disappeared from the tap-room window.

Marlowe and Rouse turned one to another in the silence of astonishment. And the name on the lips of both men, although they gave it not even a whispered utterance, was “Vytal.”

CHAPTER II

“Our swords shall play the orator for us.”

—Marlowe, in Tamburlaine.

It would be difficult adequately to describe the expressions of amazement, in face and gesture, of those who had had this fearless effrontery thrown at them. Its effect on Marlowe and Rouse was instantaneous. Both went back immediately to the table they had quitted, refraining from any further show of fight. The youth called Frazer was the first to speak.

“Who's the insolent fellow?”

“If I should fetch him,” observed St. Magil, as no answer was forthcoming, “you would see a most extraordinary man.” He went to the window. “Nay, he's gone. ’Tis always thus—up and down from hell's mouth like the devil in the play. But I can describe that face as though even now it was here before me, and, mark you, I saw it not when its mouth defied us at the window. He is well called the Wolf.”

“Nay,” interposed the poet, “save because many fear him. I drink to the man!” and Marlowe turned to Rouse.

“To the man I follow!” said the good Hugh, simply; and they drank. But the cups of Frazer and St. Magil for once stood untouched upon the table.

Before the conversation had gone further the taproom door opened, admitting a short, stout woman of

middle age and rubicund visage. Glancing quickly about from one to another, her eyes at length rested on Thomas Watkins, who, having had his usually prominent place in the tavern gossip usurped by those of higher degree, and holding no small measure of ale within him, sat fast asleep and snoring. The sight of the breeches-maker in this position so enraged the new-comer that she awoke him by the startling method of boxing his ears soundly, and commanding him to follow her without delay. With a pained air, yet much alacrity, the poor leather-seller obeyed his orders. It was, indeed, his life-long obedience to his wife's decrees that won him the pity of his fellow-men.

“There's a customer at the shop, Tom Sot,” declared the shrew, leading her husband to the bridge, “who wants you. And lucky we are if he be honest, for I must needs leave him there to guard it while I come here and get you. But Sloth's your name, and always will be. Had ever woman such a lazy clod to depend on?”

Thus she railed at the now miserable Watkins until they came to their shop at the sign of “The Roebuck,” on London Bridge. Finding it empty, the breeches-maker, with much alarm, looked up and down the street through the gathering darkness. The narrow way on the bridge was almost deserted save for a watchman slowly approaching from the London end with horn-sided lanthorn, and halberd in hand, who cried out monotonously his song of the familiar burden:

“Lanthorn and a whole candle-light!Hang out your lights! Hear!”And just across the bridge stood another man near the parapet, his tall frame sharply defined against

the sky. It was to him that Watkins went in the hope of obtaining information concerning his departed customer.

“Can you tell me, sir, did any man just leave my shop at the sign of ‘The Roebuck’ there?”

“A man did,” replied the stranger. “I am he.”

“And you were left to guard it, sir, in Gammer Watkins's absence,” complained the breeches-maker.

“I have guarded it. ’Twas but five minutes ago that I came out, and I've kept a close eye upon your doorway through every one of those five minutes. I tell you, Thomas, the time that has passed since I went out of your shop with a new pair of breeches is much longer.”

The leather-seller looked up keenly into the speaker's face. “Salt and bread!” he exclaimed; “’tis Master Vytal!”

“Yes, Tom, or Captain Vytal, as you will, being now a fighting man from the Low Countries.”

“Oh, sir, your presence brings me pleasure and consolation, I may say. How the times have changed in these few years—within, sir, and without! Have you heard about Queen Mary, how we have been delivered from her plots these two months past in a very, I may say, forcible way? Have you heard—?”

“Ay, Tom, all that, and more, too, on the road from the coast. But one thing I have not heard—how long will it take you to make me a pair of breeches?”

“But a short time, Captain Vytal. I was ever handy and quick with work for you.”

“And so, Tom, I have come back to you.”

“Ay, sir, but, alack!—the old days cannot come back. There are many, many changes since the good old times. The world, it seems to me, grows petty.”

“What! call you it petty when a queen comes to the block?”

“Nay, but look you, Captain Vytal.” He pointed to the top of the Southwark Gate. “See those heads spiked above us. They be thirty in number, yet all are but the pates of seminary priests who have entered England against the statute. Now this old bridge has had much nobler heads upon it, crowning the traitor's gate. The head of Sir William Wallace looked down on the river long ago, and later the Earl of Northumberland's. Some I have seen—Sir Thomas More's, the Bishop of Rochester's—”

“By Heaven!” broke in Vytal, “you are in no pleasant mood, Tom, on seeing me.”

“’Tis not you, captain. ’Tis”—his voice sank lower—“she,” and he pointed toward his shop. “Have you a wife yourself?”

“Nay, Tom, nor never shall have.”

“’Tis well. The thousand new statutes that are imposed upon us by her Majesty, the queen—God preserve her!—since you left, are not one whit so hard to bear as them her majesty—God preserve me!—Gammer Watkins, imposes.”

“There are two sides to every difference, Tom. Now, a little less at the ‘Tabard’—but tell me, do the citizens grow uneasy beneath these numerous decrees?”

“Nay; many are but slight annoyances seldom put in force. The wearing of a rapier longer than three feet is forbidden by law; the wearing of a woman's ruff too large is prohibited by law. And our caps should be of cheaper stuff than velvet by law, and we must not blow upon horns or whistles in the streets by law—’uds precious, there is no end to it. But there is no statute against the flogging of blinded bears, captain—I had almost forgot this afternoon's

exploit of thine. I saw it not, for when they had brought King Lud to such a pass I could not sit there, but went to the bear-house in the garden to show a country lad Old Sarcason at closer quarters. Yet I might have known it was you when Peter Sharp described the adventure.”

Vytal laughed. “I'm sorry you so soon forgot. I meant the thing to be a lasting lesson. But come, I want a pair of breeches. I go again abroad, but westward now, to the new country.”

They walked across to the shop. “I fear,” said Watkins, his voice sinking to a whisper, “you should not tarry long. Those bear-wards will not readily forgive you.”

“Now, Thomas, what has that to do with breeches?”

“Nothing, indeed,” returned the leather - seller, with a dry, crisp laugh. “Oh, but you never change, Master Vytal.”

They were but just within the shop when the needle-maker came hurrying to the bridge excitedly, with young Frazer, Marlowe, Alleyn the actor, Gorm, and a dozen others at his heels, St. Magil slowly following in the rear.

“They seek the jackanapes who dared to curse them from the window,” said Peter Sharp. “’Tis he, they say, that spoiled the bear-fight. His man, Rouse, hath started out in search, and they, being no more threatened by the giant, are bent on scouring the town. Oh, ’twill be brave sport to see the Wolf well harried.” The needle-maker looked keenly at Watkins, behind whom Vytal, unknowingly, stood concealed by the shadows of the shop.

Watkins forced a laugh. “Ay, brave sport,” said he; “but ’tis not to the town he's gone; he hath started out toward Lambeth.”

“Toward Lambeth!” cried young Frazer, who by

now stood face to face with Watkins. “Ho, for Lambeth, then; but first let us stop and invite the bearwards thither. ’Tis in part their right to end the quarrel.”

Here, perhaps, the danger would have been averted had not a new quarrel arisen of far more serious consequence, and, indeed, so fraught with import that, although but incidental, we recognize it as one of those contentions in which the very Fates themselves, seeming to join, brawl like shrews until their thread is snarled and the whole fabric of a human life becomes a hopeless tangle.

As Watkins closed the door of his shop, Sir Walter St. Magil turned back toward the ‘Tabard’ in ugly mood. The wine, which at first had exhilarated him, being now soured by his disapproval of Frazer's rashness, only added to his ill-humor. Young Frazer, on the other hand, who walked beside him, had grown merrier and even less cautious than before. Now that the Canary wine had fired his brain, other considerations were cast aside, all policy forgotten. The air of refinement and courtliness which, being so well assumed, had previously seemed genuine, left him suddenly. He became but an ill-bred roysterer, singing, as he started back, various catches of ribald songs, while Gorm, the bear-ward, arm-in-arm with Peter Sharp, followed not over-steadily, and several other tipplers, who, from their windows in the bridge houses, had seen the gathering before Watkins's leather-shop, hurried out to bring up the rear with a chorus of vulgar jesting.

At the Southwark Gate Peter Sharp, the needle-maker, who by now was leading the motley throng with an apish dance, having caught the spirit of hilarity, came to a stand-still and turned to the bearward, who was shambling after him as steadily as his

bandy legs and tipsy condition would allow. “’S bodikin!” he exclaimed. “Now tell me, jovial Bruinbaiter, didst ever see so remarkable a sight?” He pointed ahead of him to a young girl approaching the gateway on the High Street, escorted by a man who was evidently her servant. “Here's a wench with a ruff, indeed!”

The girl of whom he spoke was now within the scope of the light cast by a number of lanthorns the revellers were carrying. Seeing them, and hearing the needle-maker's rude observation, she hesitated timidly; then, bidding her servant follow her, turned toward a side street, with the evident intention of escaping insult by taking barge across the Thames from the nearest water-gate.

“A ruff that wears a wench, I should say,” corrected Frazer.

“Yes, and by donning such extreme attire,” declared the needle-maker, assuming an air of official importance, “she breaks the queen's decree. It is but the duty of all good citizens like myself to stop these outlandish practices. Do you detain her, Gorm, while I fetch shears and cut the thing as the law demands.” Whereupon the mischievous Peter ran back quickly, and Gorm, with a coarse oath, staggered forward to intercept the girl.

“Yes, a ruff that wears a wench,” repeated Frazer, evidently pleased with his own facetiousness.

“Let be,” commanded St. Magil, and would have passed on but for his youthful comrade, who, pushing the bear-ward aside, laid hold on the girl's arm, and, taking a lanthorn from one of the by-standers, held it before her face. At this her servant drew his sword and rushed upon Frazer savagely. But a steady rapier - point, unseen in the dark, met him full in the breast, so that he fell forward

groaning, and the weapon was with difficulty withdrawn.

“Nay, now, Sir Walter,” said Frazer, laughing as though nothing had happened, “this is no wench and ruff, but rather a flower, I should say, whose outer petals, drooping, form a collarette about its budding centre. It is, indeed, well to cut the petals. I shall keep them as a token;” and, leaning forward, he would have kissed the girl full upon the lips, but she stepped back quickly, with her face behind her upraised arm, and tried to elude his grasp. “Is there not one gentleman?” she cried; and then, in answer, a voice above all the laughter said, sharply, “Yes, one.” It was Vytal. A few strides had brought him from the breeches-maker's shop to the gateway, only the lodge of the bridge porter standing between “The Roebuck” and Long Southwark.

The girl now stood immediately beneath the great stone arch of the gate, her eyes flashing in the lanthorn-light. For one instant Vytal looked at her, and the light fell on his face, too. “My God!” he whispered; “it is you, come to me at last!” But whatever expression his face wore then, it meant only one thing to the crowd who watched it, particularly to the bear-ward, who had been suddenly sobered by the adventure, and to the needle-maker, who had returned, long shears in hand.

“ ’Tis the very knave we seek!” exclaimed the two, in a voice of astonishment. “Yes,” added Gorm, “and now for the reckoning.” So saying, he ran heavily away toward the river and along its bank to the Paris Garden.

“Ay, ’fore Gad!” ejaculated Frazer; “but there are other debts to pay.”

“One moment,” said the soldier; whereupon, leading the girl by the hand, he took her back to Watkins's

leather-shop, and without another word ushered her across the threshold. Standing then before the doorway by which she had entered, Vytal drew his rapier, while Frazer, throwing his riding-cloak to St. Magil, who saw with annoyance that a grave quarrel was now inevitable, came forward, with ease and grace regained, for the fracas had sobered him, too, and sober, he appeared, as we have said, a gentleman. His peculiarly boyish and almost innocent face, with its beardless chin and compressed lips, showed valor and determination, to which the ever-amused, patronizing look of his eyes added a certain bantering expression.

The crowd, whose numbers were steadily increasing, stood concentrated to one side near the Southwark Gate, giving the combatants as wide a berth as the bridge afforded between its double file of buildings. St. Magil held the on-lookers back, his own rapier drawn in case of interference. But at present there seemed to be small chance of this, for Hugh Rouse was beyond ear-shot, and Watkins, who alone in the crowd espoused the captain's cause, could do naught but argue his case in the deaf ears of the by-standers. The leather-seller's sallow face grew paler, for although he had no doubts as to the ability of Vytal's sword-arm, he had seen the hasty departure of Gorm, and knew its meaning. Unfortunately Alleyn, who might have been of assistance in case of need, had left at the first signs of bad blood, being a peaceable man by nature. We should mention, however, in addition to Watkins, as exceptions to the general ill-feeling, two men who watched the scene with a partial interest. These were Merfin, the book-seller, and Marlowe, who stood across the street under the sign of “The Three Bibles.” The young poet was looking at Vytal with eyes aflame, for suddenly

the great martial heroism of his dramas had become corporate and vivid in this man. It did not occur to him to interfere, as, breathless, he watched the fight. The conclusion of the contest was foregone in his mind, and only the dramatic element intensely absorbing.

“Now, couragio! my brave world-reformer!” cried Frazer. “I will show you that civilians are not all dullards at the art of fence. But before we cross I'd have you remember that I could send you before a justice an I would. There's a statute against ruffs that are too big, and, in troth, still another against rapiers over-long. Now yours, Master Vytal, is one of these.”

At this the excited Peter Sharp, who must needs have his say when the occasion offered, cried out from his position in the front rank of the audience: “Nay, ’tis a mere bodkin, and I should know, being needle-maker; but you will prove it, I doubt not.”

“Dolt!” rejoined Frazer, turning to Peter and the rest, “I meant that not so literally. Mark you, all rapiers are too long, an they play against the queen's decrees, be they bodkins or the length of quarter-staffs.” And, looking at St. Magil, he smiled.

“Now, meddler,” resumed Frazer, turning back to Vytal, who maintained his guard in silence, “I'll teach you the stoccata, as ’tis done before the queen. The stoccata—’tis thus!” Whereat the youth, with a quick wrist, thrust skilfully. But his blade was parried with apparent ease. “ ’Slid!” he exclaimed, betraying himself yet more the braggart, as he realized the dexterity of Vytal, nevertheless a brave braggart, which is an uncommon combination. “Body o’ Cæsar! but you know the special rules! Now this, for instance, the imbroccata,” and he thrust

again more viciously in tierce. For several minutes the rapiers crossed and recrossed, quick, slender gleams dancing in the lanthorn-light. “And this, the punto,” said Frazer, still persisting in his rôle of master, while Vytal, more than ten years his senior, spoke no word, but only fenced and fenced, controlling the other's point and awaiting an opening. “And the reverso—there—there—there again, and the passada—thus—’Slud! the bodkin stitches quickly—the tool's full of tricks—God! I'm undone—”

But no, for at this instant the rapier of St. Magil came darting forward like a snake to parry the thrust from his friend's breast, and now it was two, side by side, against the one who held the doorway. The crowd stood breathless, spellbound. Never had they seen such play of weapons.

Vytal drew a dagger with his left hand; his antagonists instantly responded. But he was willing to risk that, considering the increase of his own advantage greater than the addition to theirs. And now the rapiers played, with an under meaning, as it were, in the vicious poniards. Here was a contest between men who knew the art, and lived by it, and could live by naught else now but a successful practice of their knowledge. Up and down, to and fro, the rapiers made their way, now fast, now slower, like silver moon - rays on the river below, while hither and thither, prying about for an open spot, the flat poniards ran with far more venom though less grace.

And still Vytal held his ground, even gaining at the last, for St. Magil breathed heavily, and the youth beside him had gone white as death.

But it was then that several new-comers, led by Gorm, the bear-ward, entered the bridge street by the Southwark Gate. Having broadswords ready drawn and curses on their lips for Vytal, their intention

was evident. One the people recognized as him who had been flogged instead of the blinded bear he had been flogging. Their onrush against the soldier, however, was delayed for an instant by the sight of the furious fight before them. On seeing them, Vytal's face grew graver. “Curs!” he muttered, and then, in a voice just loud enough to rise above the clash of steel, “Watkins, seek Rouse!—the ‘Tabard!’ ”

At this, the breeches - maker, upbraiding himself for his demented negligence, strove to break through the throng, but could not. In despair, he groaned aloud. Just then, however, Vytal found Frazer's hilt with his rapier - point, and, maintaining his guard for the instant with dagger alone, threw the weapon high in air, and across the street, where it fell, ringing, at the feet of Christopher Marlowe. And Vytal's voice rose above the clamor of invective in a short, sharp cry: “Hugh! Roger! To me!” For the bear-wards from the garden were now opposing his rapier with their heavy blades. Yet he still held the door, rendering entrance to the breeches-maker's shop and to the girl within it as difficult as ever. He heard a voice from across the threshold imploring him to save himself, if he could, by leaving the shop-door—and that low voice, coming to him from behind the barrier, then again from an upper window, where the girl watched with wonder his gallant defence of her, only nerved his arm to the more strenuous endeavor.

We have said that the rapier of which Vytal had deprived Frazer fell at the feet of Marlowe. It came like an invitation to him—almost a command. Similarly inspiration had come more than once to fire his genius and kindle the flame that irradiated his poetry, but here for the first time inspiration shone to show

him another outlet for his ardor; the lustre of mere portrayal paled before the forked lightning of those swords at work, while his thoughts, at first suggesting some future depiction of the scene, gave way to hot impulse. His blood ran riotously in his veins, and as he leaped forward to Vytal's side with Frazer's rapier ready, all his art was the art of fence, all his spirit the spirit of action.

But his opportune aid, though immediately appreciable in holding back the soldier's assailants, was soon diverted by the latter to another course.

“Quick!” said Vytal, in a low voice. “Go you in by the door behind us. Up—” his words came disjointedly, being broken by some extra - hazardous thrust or parry demanding unusual attention—“up, there—through the shop—ah, they almost had you—control his point another minute—take her with you through the porter's lodge—it can be done—quick!—and then whither she will—to some place—of safety—but remember the place—meet me at the ‘Tabard’ later.”

“Meet you!” ejaculated Marlowe, still with eyes on every movement of the adversaries. “No man could hold out singly—against—this army. I came to save your life—not for some intrigue.”

“An you call it that,” returned Vytal, who was now pressed closer than ever by St. Magil, Frazer, and the cursing bear-wards, “’twere better—to fight against me! Could you defend the door, I'd go myself—quick!—the game fails us— Save her—’tis what I fight for—see—ah, they have us; we're lost an you tarry longer—quick—quick, into the shop—” and with that, Vytal, assuming a more aggressive method than hitherto, so drove back his opponents, by the sheer determination and boldness of his attack, that Marlowe, finding space to retreat, and being

persuaded by the other's vehemence, pushed the shopdoor open behind him, and, with his rapier still in play, stepped back across the threshold. Once within the shop he closed the door, to which Vytal fell back again slowly, and, maintaining his old position, made further ingress for the moment impossible.

But the odds were now almost hopelessly against the soldier. Frazer had borrowed a broadsword, and, together with St. Magil and three of the bear-wards, who out of six alone remained unwounded, sought to break through Vytal's wonderful defence. Fortunately only St. Magil and his companion were dexterous swordsmen. It was the numbers, not the skill, of his additional opponents that Vytal feared. But Frazer's broadsword, although somewhat unwieldy in an unaccustomed hand, by its mere weight had nearly outdone the light rapier opposing it. The soldier, therefore, sought to keep this heavy blade entirely on the defensive, realizing that if once Frazer were allowed to swing it freely it would doubtless strike through the cleverest rapier parry that could possibly seek to avert its downward cleavage.

Few contests have shown a shrewder scientific skill in fencing than Vytal now pitted against the superior force of his antagonists. Thrusting viciously at Frazer, he appeared to neglect his own guard, save where he opposed his poniard against St. Magil's rapier. By this feint he accomplished a well-conceived end, rendering Frazer's great sword merely a defensive weapon, and exposing his breast invitingly to the foremost of the unsuspecting bear-wards, who lunged toward the opening so recklessly as to neglect his own defence. In that instant Vytal's rapier, like lightning, turned aside from its feigned attack on Frazer and pierced the bear-ward's breast.

As the mortally wounded man fell back, momentarily

hindering the onslaught of his friends, the voice of Gammer Watkins reached Vytal from within the shop. “Fool!” she cried to him, “you fight for naught. The bird ha’ flown already with another—ha, the coxcomb robs you of your game—”

But it was for this that Vytal waited. His plan concerning the girl's safety being now successfully executed, left him free to act entirely for himself. He saw the folly of attempting to hold out longer against so great odds, with no hope of an actual victory. His strength, although not yet seriously impaired, must inevitably sooner or later be exhausted, whereas his opponents could harbor their own by alternately falling back to rest and regain their breath while others in turn kept him occupied.

With this realization, Vytal set his back against the door, seeking to open it and enter the shop, but the latch held it against him. He dared not call to Gammer Watkins for fear of betraying his plan of escape to his adversaries, and so, to their amazement, with not a trace of warning he flung the poniard from his left hand into the face of St. Magil, and, darting that hand behind him, lifted the latch. Instantly he was within the shop, followed by Gorm, Frazer, and as many of the throng as could make their way with a headlong rush after him. They were now like hounds lusting for the blood of a stag at bay, excepting two among the foremost to enter, whether they would or not—namely, the terrified breeches-maker and the watchman, who, lanthorn in hand, had witnessed the contest with a gaping interest instead of seeking to end it as the law demanded.

From the shop's entrance straight to its rear wall ran a dark passage, at the end of which a window opened high above the Thames. Beside this passage a narrow stairway led to one or two upper chambers.

Mounting quickly to a step midway on the staircase, the breeches-maker was followed by many others, who, eager to gain view of so desperate a conflict and to see the final harrying of the prey, pulled one another down from the coveted vantage-point, trampling on the weaker ones that fell. The watchman, gathering up his long gown, had succeeded in arriving at the breeches - maker's side, thanks to his official superiority, and now, as he held his lanthorn out at arm's-length over the passage, the dim light through its horn screens fell upon Vytal and others in the hallway, who, headed by Gorm and Frazer, were pressing their game with redoubled fury. The staircase groaned and creaked beneath its trampling burden, the house seeming to echo the clash and whisper of steel, while now and again a bitter oath rang out above the varied clamor. For the rage of Vytal's enemies only increased as it became evident that the number of those capable of direct attack was necessarily limited by the narrow passage.

Thus he still remained unscathed.

Assuming again the defensive until he had fallen back to a spot immediately beneath the watchman's overhanging light, he suddenly struck upward with his rapier, and, knocking the lanthorn from its holder's grasp, brought to the shop utter darkness save for a glimmer of starlight that shone faintly through the rear window.

Then, after the first bewildering moment of gloom, when hoarse cries for lights drowned softer sounds, and the staircase voiced its strain with new groans under the stampede, and each swordsman mistook his neighbor for the enemy, with the result of blundering wounds in the black passage—after that moment of havoc there came a lull, a loud volley of oaths, and the breeches-maker's laugh was heard crackling

like dry wood amid the roar of an angry flame. For one instant even the patch of sky framed by the casement was obscured, and those looking toward the window saw it filled by a dark form that came and went as a cloud across the moon.

Vytal, having gained the sill, had leaped far out into the Thames.

Book IICHAPTER I

“What star shines yonder in the east?The loadstar of my life.”

—Marlowe, in The few of Malta.

“The 8th we weighed anchor at Plymouth, and departed thence for Virginia.”

With this terse statement of fact an old-time traveller is content to record the beginning of a memorable voyage.

It was on the 8th of May, 1587, that two ships—one known as the Admiral, of a hundred and twenty tons, the other a fly-boat—set sail westward from the coast of England. There was also a pinnance of small burden carried on board the larger vessel, and ready to be manned for the navigation of shallow waters; but this, like a child in arms, was a thing of promise rather than present ability.

The aim of the voyage is briefly outlined: to establish an English colony in Virginia, where previous attempts at settlement had resulted in desertion and no success; to find fifteen men who had been left the year before to hold the territory for England; to plant crops; to produce and manufacture commodities for export; to extend commerce and dominions; to demand the lion's share between possessions of France and Spain—the great central portion of a continent; and thus in all ways first and last to uphold the supremacy and majesty of England and the queen.

The ships had been provisioned at Portsmouth and Cowes, where many of the colonists embarked, including among the notable ones two Indians, Manteo and Towaye by name, who, several years before, had been brought to England from Roanoke by Arthur Barlow. At Portsmouth, among others, three soldiers came aboard, booted and spurred as though from a recent journey in the saddle; the one slim, tall, and bronzed by the sun; another no shorter, but broad and heavy in proportion; the third laughable in aspect, being fat, as if, like a stage buffoon, he had stuffed a pillow in his doublet, and leading, much to the astonishment of the passengers, a bearcub that copied his own waddling gait, and followed on a chain of bondage with remarkable fidelity.

In the evening one of these soldiers stood alone on the Admiral's high stern, a motionless figure, cleancut against the sky. His eyes, blue like the deep sea, looked back toward the receding coast-line, fixed on the dissolving land with a resigned fatality and regret.

With the sun, westward, the two ships went down slowly over the horizon, leaving England a memory behind—a memory, yet very real, while the haven, far ahead, somewhere beneath the crimson sky, seemed but a dream that could not shape itself—a dream, a picture, bright, alluring, undetailed, like the golden painting of the sun. Tall and erect as a naked fir-tree the man stood on the top deck in the stern—still stood when night came and there was not even a melting horizon to hold his gaze—still stood as though to turn would be to wake forever from a vision beside which all things actual must seem unreal. But at last he turned resolutely and, drawing his cloak about him, glanced off toward the darkening west; then, with a word to one and another

as he passed his fellow-voyagers, he sought the ship's master to discuss plans for the maintenance and general welfare of the colony.

As he was about to enter the main cabin a soldier accosted him. “The die is cast, captain.”

“Yes, Rouse; we have done well in starting. May ill fortune throw no better.”

“Nay,” observed the Saxon giant, in low tones. “But already I mistrust this Simon Ferdinando, the master of our ship.”

“He is but a subordinate. We have the governor and his twelve assistants to depend on.”

“Ay, captain, and you.”

“I am one of the twelve.”

“God be praised!” said Hugh, fervently. “But there's mischief in Simon. I always mislike these small men.”

“You forget our Roger Prat, no higher than your belt; and yet, Hugh Rouse, even you have no greater fidelity.”

“’Tis true, but his breadth is considerable. Cleave him in twain downward, as he's ofttimes said, then stand his paunch on the top of his head, and Roger Prat would be as tall as any of us. ’Tis merely the manner of measurement.”

“In all things,” said Vytal, with a fleeting smile, and wishing to see this Ferdinando, the Admiral's master, in order to judge of the man for himself, he entered the main cabin.

With Ferdinando he found John White, the governor appointed by Sir Walter Raleigh, at whose expense the voyage had been undertaken. The governor, whom Vytal had met but once before, was a man of medium stature and engaging personality. His expression, frank and open, promised well for sincere government, but his chin, only partly hidden

by a scant beard, lacked strong determination. Ferdinando, on the other hand, to whom Vytal was now introduced for the first time, so shifted his eyes while talking, much as a general moves an army's front to conceal the true position, that candor had no part in their expression; while his low forehead and close brows bespoke more cunning than ability. He was, moreover, undoubtedly of Latin blood; therefore, in the judgment of Englishmen, given rather to strategy than open courage. Nevertheless, his reputation as a navigator had not yet suffered. That he relied much on this was made evident by his first conversation with Vytal. In answer to the latter's questions concerning matters that bore directly on the management of the little fleet, Ferdinando replied, “Since Sir Walter Raleigh has wisely left the management to me, you need have no fear, I assure you, regarding your welfare.”

“What, then,” asked Vytal, “if you object not to the inquiry of one who studies that he may duly practise, what, then, are the main rules we observe?”

To this the master made no answer, but, with an air of indulgent patronage, handed Vytal several sheets of paper well filled with writing. The soldier glanced over them, and read among others the following orders: “That every evening the fly - boat come up and speak with the Admiral, at seven of the clock, or between that and eight; and shall receive the order of her course as Master Ferdinando shall direct. If to any man in the fleet there happen any mischance, they shall presently shoot off two pieces by day, and if it be by night two pieces and show two lights.”

When Vytal had read these and many similar articles

he turned slowly to Ferdinando. “A careful system. Is it all from your own knowledge?”

“From whose else, think you?”

“I make no conjecture, but only ask if it be yours and yours alone.”

“It is,” replied Simon, and turning to John White, the governor, who had said little, he added, “Your assistant, worshipful sir, seemingly hath doubt of my word.” White turned to Vytal questioningly.

“Nay,” observed the soldier, “I would show no doubt whatever,” and so saying he left the cabin.

Similar conversations followed on subsequent evenings, Ferdinando boasting much of his seamanship; and once the governor went out with Vytal from the room of state. “You mistrust our ship's master, Captain Vytal, although you would show it not on considering the expedience of harmony. Wherefore this lack of faith?”

“Because the orders and articles are framed exactly upon the plan of those issued by Frobisher in 1578, when he sought a northwest passage, and by Sir Humphrey Gilbert in 1583, changed, of course, to suit our smaller fleet. The worthy Ferdinando has effected a wise combination; he has done well—and lied in doing it.”

The governor looked up into Vytal's dark face for the first time, searchingly. “How came you to know?” he queried.

“I remember things.”

“But where—”

“I forget other things,” was Vytal's answer. “An you'll permit me I'll leave you. There's a man's face under that light”—he was walking toward it now alone—“a familiar face,” he repeated to himself, and the next minute exclaimed in amazement, “’Tis the man who fought beside me on the bridge!”

“Ay,” said the poet, smiling, “’tis Kyt Marlowe,* at your service in reality.”

Vytal scrutinized him keenly, Christopher returning the gaze with a look of admiration that increased as his eyes fell once more on the so-called bodkin at the soldier's side. “You are readier with that implement than with your tongue,” he observed, finally.

“The most important questions,” returned Vytal, “are asked with an upraised eyebrow, an impatient eye.” There was an abrupt cogency and gravity of manner about the soldier that sometimes piqued his fellows into an attempted show of indifference by levity and freedom of utterance. They made as though they would assert their independence and disavow an allegiance that was demanded only by the man's strong, compelling personality, and seldom or never by a word. He was masterful, and they, recognizing the silent mastery, must for pride's sake rebel before succumbing to its power. Marlowe, with all his admiration, born of the soldier's far-famed prowess and imperious will, proved no exception to this rule.

“I marvel,” he observed, with a slight irony and daring banter, “that so dominant a nature is readily subject to the coercive beauty of women's faces. Even the Wolf's eyes may play the—”

“What?”

“The sheep's.” It was a bold taunt, and the poet was surprised at his own effrontery. But like a child he saw the fire as a plaything.

“Explain.” The word came from Vytal quietly and with no impatience.

* As there is absolutely no reliable record of Marlowe's personal life and dwelling-place at this time, I have felt justified in attributing his generally acknowledged absence from London to a Virginia voyage.“Oh, there have been other beguiling faces, so I've heard. A tale is told—” he hesitated.

“Of whom?”

“Of you.”

“What is it?”

“A tale vaguely hinting at a court amour. ’Tis said the queen would have knighted a certain captain for deeds of valor in the south; but at the moment of her promising the spurs, she found him all unheedful of her words, found him, in fact, with eyes gazing off entranced at a girlish face in the presence chamber, the face of her Majesty's youngest lady-in-waiting. To those who saw our Queen Elizabeth then and read her face, the issue was seemingly plainer than day, blacker than night.

“ ‘Nay, Captain Vytal,’ said the queen, her lip curling with that smile of hers which is silent destiny itself—‘nay, she is not for you; nor yet is knight-hood either. Our boons are not lightly thrown away, so lightly to be received.’ And then, says the tale, she paused with a frown, to cast about for an alternative to the benefit she would, a moment before, have conferred most graciously. From her dark expression the courtiers supposed that ignominy would take the place of compliment in the soldier's cup. But at this instant her Majesty's favorite, Sir Walter Raleigh, ‘Knight of the Cloak,’ made bold to intervene on his friend's behalf. ‘An I may venture,’ he said, in a low voice, ‘to argue the case before so unerring a judge, I would assert from my own experience that this man's first sudden sight of a divine radiance has dazzled and blinded him, so that perforce he must seek a lesser brilliancy to accustom his eyes to the perfect vision. The moth, despairing of a star, falls to the level of a candle.’ Then her Majesty turned to Sir Walter with a changing,

kinder look. And before she could glance again at the captain to seek for an acquiescence to the flattery (which, I believe, would have been sought in vain, for the soldier is said to be desperate true), before she could harbor a second resentful thought, the knight spoke again. ‘There is an augury about this Captain Vytal,’ he declared, ‘a prophecy sung at his birth by a roving gypsy maid. “He shall be,” said she, “a queen's defender—the brother of a king.” I pray your Majesty leave him free to prove the truth of this prediction. There is but one queen to whom it can refer, for there is one queen only under heaven worthy of the name. Of the king I know not, but it may be that the king, too, is our most gracious sovereign, Elizabeth, for while in beauty and grace she is a queen, in majesty and regal strength no monarch is more kingly. “A queen's defender—the brother of a king.” It has all the presumption of a prophet's words. For the latter condition is impossible; none can ever rise so high as to be honored by your Majesty with the name of brother’—Sir Walter's voice sank almost to a whisper—‘indeed,’ he added, daringly, ‘none would choose the name. But—a queen's defender—that means more.’

“Her Majesty turned to the soldier. ‘Would you be your queen's defender to the end?’ she demanded, sternly, but now without menace in her voice.

“ ‘To the death.’

“ ‘Appoint him,’ she said to Raleigh, ‘where you will. The spurs are yet to be won by the defence.’ ”

Marlowe paused, his story finished. “And thus, you see,” he added, as Vytal made no rejoinder, “I was right in saying that more than one fair face had hazarded your welfare.”

“No, you were wrong.”

The poet's dark eyes opened wide with a query,

but he said nothing in words, for the feeling of pique had already passed with his airy rebellion against the other's trenchant monosyllables.

“The face in court,” avowed Vytal, as though half to himself, “and the face in the Southwark Gateway, belong to one and the same woman. I ask you outright wherefore you met me not at the ‘Tabard Inn’? Whither went the maid?”

“Now there,” replied Marlowe, his eyes cast down, “I must play the silent part. In truth, I know not.”

“Know not?”

“Nay, for when we had come safely from the porter's lodge, she demanded that I should take her to a barge, that she might go thereby to London. We had no more than set foot within the boat, and I was questioning her as to the directions I should give the waterman, when another wherry came beside us, seemingly just arrived from across the river, and a man in that, scrutinizing us, slowly spoke to her. Then, thanking me, and bidding me thank you for that which she said was beyond all payment, she entered the wherry with the other, and was quickly conveyed toward London.”

For several minutes Vytal was silent; then at last he asked, quietly, “Did the man call her by name?”

“By the name of Eleanor.”

“And she said no more of me?”

“Yes, much, as we went toward the river; much concerning your gallantry; and from the barge wherein she sat, beside her new-found friend, she cried back to me that with all speed they would send you aid to the bridge. ’Tis evident the assistance came.”

Vytal made no denial. The method of his escape was but a trifling detail of the past. He shrugged his shoulders. “ ’Tis well I strive not only for reward.”

“Was it not reward,” asked the poet, “to look once upon that face with the eye of a protector?”

“Yes,” said Vytal.

“And to see her bosom heave gently to the rise and fall of the universal life-breath tide, which alone hath poetry's perfect motion, and to note its trouble in the rhythm as in the breast of a sleeping sea—was that not recompense?”

“Yes.”

“And her eyes—the privilege to tell of them, to wonder vainly, and seek with all poetic fervor for words that hold their spirit—is it not invaluable reward?”

“Yes,” said Vytal.

“They might well,” declared the poet, “be the twin stars of a man's destiny.”

“Yes,” and the two men, standing amidships near the rail, looked at each other steadfastly, Marlowe at the last turning his gaze downward to the starlit water. It seemed to Vytal as though a spell held his eyes fixed on the poet's face, across which the lanthorn gleams fell uncertainly, intensifying a shadow that came not only from outward causes. And the spell possessing Vytal, portended some new condition—change—tidings—he could not tell what.

Suddenly Marlowe, as if by an impulse, caught his arm. “Vytal, she is there.” He pointed to the light of the fly-boat far behind. “She came aboard at Plymouth with a slim, weak-seeming fellow whom I take to be her brother, for his name, like hers, is Dare—Ananias Dare, one of the governor's assistants. ’Twas he who met her at the bridge. Vytal, she is there.”

The soldier followed his gaze. “There!” The word came in a vague tone of wonder, as from a sleeper at the gates of a dream; and with no comment,

no reproach, no question, Vytal went away to be alone.

For many minutes after he had gone, Marlowe stood looking into the shrouds, but at last, as though their shadows palled on his buoyant spirit, he wandered along the deck, singing to himself a song of genuine good cheer. And soon, to his delight, the notes of a musical instrument, coming from somewhere amidships, half accompanied his tune. Eagerly he sought the player, and came on a scene that pleased him. For there against the bulwark sat a stout vagabond cross-legged on the deck, strumming merrily on a cittern, as though rapidity of movement were the sole desire of his heart. The instrument, not unlike a lute, but wire-strung, and therefore more metallic in sound, rested somewhat awkwardly on his knee, for his stomach, being large, kept it from a natural position. The player's fat hand, nevertheless, with a plectrum between the thumb and fore-finger, jigged across the strings, his round head keeping time the while and his pop-eyes rolling.

“’Tis beyond doubt that Roger Prat,” said Marlowe to himself, “Vytal's vagabond follower, and avenger of King Lud, the bear.”

Ranged around this striking figure were many forms, dark, uncertain, confused in outline, and above the forms faces—faces vaguely lighted by an over-hanging lanthorn, and varied in expression, yet all rough, coarse, uncouthly jubilant with wine and song.

In the middle of this half-circle a woman sat predominant in effect. Her hair, riotous about her neck, shone like gold in the wavering gleam; her red lips were parted witchingly. She was singing low a popular catch, in which “heigh-ho,” “sing hey,” and “welladay,” as frequent refrains, were the only intelligible phrases.

On seeing Marlowe she rose, even the refrains becoming inarticulate in the laughter of her greeting.

“Why, ’tis Kyt!” she cried—“Kind Kyt, the poet!” whereat, much to the amusement of her admiring audience, she stepped lightly toward him and, throwing her head back, asked outright, “Saw you ever so comely a youth?” then, with a coquettish, bantering look at the cittern-player, “Good-night, Roger Prat, I'm going,” and she led Marlowe away into the darkness.

“Gyll!” he exclaimed, “Gyll Croyden! Is't really thee? How camest thou to leave thy Bankside realm, thy conquest of rakes and gallants?”

She laughed anew at this and shrugged her shoulders. “How camest thou, Kyt Marlowe, to leave thy Blackfriars, and thy conquest of play-house folk, for the wild Virginia voyage?”

The poet laughed as carelessly as herself. “Because ’tis wild,” he answered. “Indeed, I know no other reason.”

“It is my own,” she said. “I grew stale in London.”

“Not thy voice, Gyll. Methinks ’tis all for that I like thee.”

She pouted, then smiled contentedly. “Come, Kyt, away into the bow. I'll sing to thee alone.”

And in another part of the ship Vytal was recalling one of the rules of sailing, “That every evening the fly-boat come up and speak with the Admiral, at seven of the clock, or between that and eight; and shall receive the order of her course as Master Ferdinando shall direct.”

“To-morrow at seven of the clock,” he repeated, “or between that and eight.”

CHAPTER II“In frame of which nature hath showed more skillThan when she gave eternal chaos form.”

—Marlowe, in Tamburlaine.

Although on the second night there came but little wind, the Admiral's master found it necessary to strike both topsails in order that the less speedy fly-boat might come up for his orders, as the rule demanded. But even with this decrease of canvas the sun had set and darkness fallen before the two ships lay side by side. At last, however, being lashed together with hawsers, so that men might pass from one to the other without difficulty, they drifted beam to beam—two waifs of the sea, seeking each other's companionship on the bed of the dark ocean, like children afraid of the night. But that night, at least, was kind to them, though only the lightest breeze favored their progress. The sea lay smooth as a mountain-guarded lake, save where the two slow-moving stems disturbed its surface, awakening ripples that rose, mingled, and dispersed, to seek their sleep again astern. And the ripples played with the waiting beams of stars, played and slumbered and played again, but beyond the circle of this night-time dalliance all was rest. Here the ripples were as smiles on the face of the waters, and the gleams were the gleams of laughing eyes; but there, far out, the sea slept, with none of this frivolous elfinry to break its peace.

Yet even now, up over the ocean, as a woman who rises from her bed and seeks her mirror to see if sleep has enhanced her beauty, the moon rose from behind a long, low hill of clouds, rose flushed as from a passionate hour, and paled slowly among the stars.