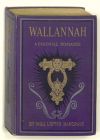

WALLANNAHA COLONIAL ROMANCE

Illustration of Door KnockerBY WILL LOFTIN HARGRAVE

North Caroliniana Collection B.W.C Roberts

Bookplate

H.A. Buchanan.

Marion,

March 1902. Virginia.

"YAUNOCCA! YAUNOCCA!" HE CRIED. (See page 297.)

WALLANNAH A Colonial Romance ByWILL LOFTIN HARGRAVE

vignetteRICHMONDB. F. JOHNSON PUBLISHING COMPANY1902

Copyright, 1902

By B. W. HARGRAVE

All rights reserved

CONTENTS| PAGE | ||

| CHAPTER I | The Spinning of the Web | 9 |

| CHAPTER II | The Theft of the First-Born | 23 |

| CHAPTER III | A Meeting and a Parting | 33 |

| CHAPTER IV | Consuming Flames | 42 |

| CHAPTER V | Some Further Tricks of Fate | 52 |

| CHAPTER VI | A Good Man Meets His Wife | 71 |

| CHAPTER VII | A Bit of History | 81 |

| CHAPTER VIII | “Call That Man a Frencher!” | 96 |

| CHAPTER IX | A Knightly Deed and a Forewarning | 111 |

| CHAPTER X | The Governor Does Some Plotting | 119 |

| CHAPTER XI | Conscience and a Failure | 132 |

| PAGE | ||

| CHAPTER XII | Beauty, Love and Remorse Page | 145 |

| CHAPTER XIII | A Hunter Hunted | 156 |

| CHAPTER XIV | A Cracked Skull and a Victory | 165 |

| CHAPTER XV | Motier Receives Company | 177 |

| CHAPTER XVI | The Story of Jack Ashburne | 189 |

| CHAPTER XVII | The Gift of the White Rose | 200 |

| CHAPTER XVII | A Temptation That Went Astray | 211 |

| CHAPTER XIX | Men-at-Arms a-Marching | 225 |

| CHAPTER XX | The Battle of the Alamance | 234 |

| CHAPTER XXI | Several Mysteries Spring Up | 243 |

| CHAPTER XXII | An Awkward Surprise | 255 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | A Move Forestalled | 268 |

| PAGE | ||

| CHAPTER XXIV | Some Heathen Justice Page | 279 |

| CHAPTER XXV | Wallannah Manita | 293 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | A Pair of Dead Indians | 307 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | Caged Birds—With a Little Sword Play | 322 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | Reckoning an Account | 333 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | Cupid Seems in Trouble | 343 |

| CHAPTER XXX | The Fortune-Teller Plays a Hand | 354 |

| CHAPTER XXXI | Unpleasant Revelations | 366 |

| CHAPTER XXXII | Murder | 379 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII 627 | Jeremiah Lane | 393 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | “To My Mother—God Bless Her!” | 407 |

| CHAPTER XXXV | In Which the Expected Happens | 422 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| “Yaunocca! Yaunocca!” he cried | Frontispiece |

| “Remember all that I have told you” | 13 |

| And they committed Bowzer to his grave | 62 |

| “Speech is free!” retorted the woodman, his voice louder than before | 101 |

| The glass fell from Simon's hand and was shattered on the hearth | 134 |

| The face which she turned toward him was aglow with pleasure | 146 |

| “Oh! Motier,” she cried, standing in front of him | 218 |

| He raised his hat and smiled | 412 |

WALLANNAH

CHAPTER I The Spinning of the WebIT was far back in the day when, save for a few thousand planted acres, the forests covered North Carolina from Currituck to Fear and from the peaks of the Unakas eastward to the slender breakwater, which, bent like a giant's knee, lies between Pamlico and the troubled seas.

Over all the land lay the hush of an autumn noon, a quiet deeper even than the stillness that comes before the dawn. In the part of that country where the Neuse creeps down to the great sweep that turns it eastward to the sound, the pines pointed through the breezeless air to a sky that, hard and hot, blazed like a glowing brazen dome. The wood-fringed river, broad as the sea of Bahret el Hijaneh, stood still at the poise of the tides, lapping its shores so faintly that its rippling could be heard only by the frog that blinked its yellow eyes among the reeds, or by the deer that stood flank deep in the cooling waters on the shoal, a rod off shore.

It seemed as though the length and breadth of the wooded land had never felt the weight of the foot of

man. Under the pines a bed of parching needles covered the earth and the creatures that crawled upon it; flowers, bright and vari-colored, and grass, knee high and fresh with moisture, lay in unbroken expanse over the sweep of the level land beneath the elms; and the lowlands at the river's brink were deep in ferns and rushes. But nowhere did a road divide the glades or a pathway wind about among the trees. Pines were there, tall and straight and great of girth, but the blazoned scar of the woodman's axe had never drawn their blood. All was wild, and unprofaned by the settler's ruthless hand, although but ten leagues further east lay New Bern, a restless, busy town girt about by the tilled and fertile lands of many planters.

But the forest, void though it seemed of human life, harbored in its sultry depths a savage world of its own people. Ever and anon a dusky face would peer through the vine-laced undergrowth, a bronzed arm would straighten to the bending of a bow, and a feathered arrow, gleaming white for a half-spent second, would flash across a sunny glade and sink a third of its length in the side of a fawn that thought itself at peace with the whole world.

Back a little way from the river and deeply bowered in the woodland, a tiny spring, bubbling from the ground, twisted down a grassy hillock toward a stream that wound its way into the Neuse. And there, as still as the trees about her, with head uplifted and her hair falling back from her face, stood an Indian girl. She leaned a little forward, as one who listens for a far-off sound. After a moment her lips, slightly parted, bent in a half-formed smile, as from the depths

of the wood came the mewing cry of a cat-bird. The muscles of her bare, rounded throat quivered the veriest trifle, and back went the answering call, clear and strong. Then, stepping quickly to the edge of the glade, she parted the bushes and looked down the slope toward the rivulet below. A long time she stood there, her graceful figure strongly marked against the green about her. Thrice did the wild-bird call awaken the forest echoes, and thrice went back the answer, sweet as the nightingale's song.

A fair picture she made, standing proudly in the glory of her youth. Her arms were bare to the bracelets that girt them above the elbows. Below her fringed skirt glistened the fantastic beadwork of her buckskin leggings; and her feet, small and shapely, were clothed in moccasins bearing on the instep the sign of a red-rayed sun. The lines of her figure were full and round, and her face, framed with a flowing wealth of coal-black hair, and lighted with great eyes of liquid brown, was as lovely a face as God had ever given to woman.

A pity it was that Sequa was a savage. True, her grandfather had been a king, but the blood of pagan kings carries no heritage of godliness. Her notions of lying and of theft, and of many things other than these, were far removed from the civilized standard. If Sequa made mistakes it was largely because she knew no better. At the same time, had her wishes led that way, she might have learned to know the good from the evil. So the facts can hardly excuse the girl from the several misdeeds which must be set against her account.

The heathen simplicity of Sequa's nature came plainly into view when she smiled with great, uplifted eyes into the face of the tall young man, who, threading his way among the trees, bounded across the rivulet and climbed to the mound beside her. And something of the same freedom came into play when he dropped his hand to her rounded waist, and she raised her arms, and drawing down his head, kissed him until he turned his face aside and cried for a chance to breathe. Then, each holding the other's hand, they walked across the glade to a spot which the sun's heat had not yet touched. There she sat, leaning her shoulders against the trunk of a towering elm; while he, resting lazily beside her, played with the rings on her fingers and talked to her in English and in Cherokee.

Had Sequa's eyes been trained to read in the face of man the lines of good and evil which were there, she might have looked with less favor upon the features of John Cantwell. True, his face was comely in a way. His forehead was broad and high, his eyes large and dark, and his skin so clear that the blue of his veins showed strongly on his brow and his temples. And, too, his mouth was of goodly shape, and his chin was firm and squarely moulded. All these things could Sequa see; and she found them pleasing. But the deep eyes had something in them which told the great, black lie of his life; and at times a look bespeaking a serpent's guile crossed his face and left a shadow not good for a knowing eye to look upon. But these were the things that Sequa could not see; so all that he seemed—to her—was pleasing.

They stayed in their forest bower a long time, until

"REMEMBER ALL THAT I HAVE TOLD YOU."

the sun had gone far down to the west, and the woods had cooled and were musical with the songs of birds and the chatter of the squirrels in the tree-tops. And through all that time they plotted and planned, Sequa and her pale-faced lover; she laughing and making a huge jest of the matter in hand, he half serious and half mocking, but, through it all, masterful and unrelenting.

He had told her of a house that stood in the forest beyond the hamlet of Neusioc, a day's journey toward the river's head, and of a child within that house which must be stolen and brought to him by noon of the third day after. And Sequa, not knowing that Mary Ross, the mother, was Cantwell's truly wedded wife, laughed scornfully at the folly of the woman who had borne the child, and entered into the project with all the zest of her heathen spirit.

“And now,” said Cantwell, when the plot was laid, “remember all that I have told you; and be careful with the child, and bring him to me alive and well.”

“But if she—the foolish woman”—said Sequa, in her native tongue; “if she sees me, what shall I do then?”

“She cannot see you. Wait until she leaves the child alone in the room; then creep in and take him from his bed and run down the path by the river. When she comes back—”

With a low laugh, she interrupted him.

“If I could only see her then,” she cried, exultantly. “She will laugh and cry, and make queer sounds, like the Sinnegar squaw with Tetah's arrow in her throat.

All this will she do because her skin is white and her heart is faint, and because she knows as little as her child of the wisdom that is Sequa's.”

They looked at one another and laughed, the one merrily as from a light heart, the other with the ring that tells of venom in the soul. Then, rising to her feet she stretched out her bronzed arms with an indolent gesture of command. “Come, Great Heart,” she said, with the deep love-light in her eyes, “soon the sun will leave us in the wood, and Sequa has yet a long journey to make. Ah!” she laughed, as breaking from his embrace she darted through the bushes and led the way down to the creek; “I feared you had forgotten! But you are so strong—you would crush me like a bear. Did she—the foolish one—love you as I do? No; she could not, for her face and her heart are white, and her blood runs slow like the water in yonder river. She loved you so little that she must bear the child and love him more than you. But Sequa is wise, and gives all her love to you. And who is happier, the foolish one, or Sequa?”

They went down the hill, he with an arm about her waist—a lithe, firm waist, muscled with steel, yet soft and yielding as a child's—and she brushing aside the branches and vines that bent across their way. Lifting her high above the water, he carried her across the stream; then dropping her, amid a shower of kisses, into the field of waist-high ferns, he led the way up the further bank, and together they went through the wood.

And the brook sang and danced foam-flecked over its pebbles; the cardinal-bird flamed gaily across the

sunlit open; and here and there the river, resplendent as a stream of gold, gleamed through the green of its banks of willow. Sequa, radiant in her pagan beauty, laughed and sang as she leaped from mound to fallen log, and from log to beds of fragrant flowers. And in that shining, favored land, all was fair and bright save only the eyes of John Cantwell, gleaming ominously with sinister craft—the one discordant note in the symphony of beauty.

It was twilight when Cantwell, returning to the village of New Bern, walked slowly down the street, greeting with kindly smile and cheering word the scores of friends whom he passed on the way. Pausing a moment at the great carriage-block before his house, he looked long and earnestly down the broad expanse of the Neuse as it stretched toward the sound; then, with more serious mien, he opened the gate, and walked up the graveled walkway to the white-pillared house that reared its noble front from a terrace of green and a maze of tulip-beds and blooming rosebushes. Before the oaken door he paused again; and once more his eyes sought the deepening haze of the seaward sweep of the river. But the Leopard, freighted with the wealth of the West Indies, and flying Cantwell's yellow pennant, was still beyond his sight—and twelve days overdue.

Opening the door, Cantwell mounted the stairway and entered his room—a luxurious apartment. The windows were richly curtained, and a canopy of soft brocaded silk hung over the great bedstead. Upon the walls were rare pictures, and on a pedestal in a windowed alcove stood a bronze statue of Hermes.

The classic mantel was set with carved vases of marble, and back of these was a silver-framed mirror, reputed to have come from a pirate brig captured off Cayo Verde and the Ragged Islands. The floor was bare, and shone with purest wax, and on its glistening expanse lay rugs of fur, and of silk from the looms of Azerbijan, each worth the ransom of a Bolobo slave. The massive mahogany furniture, with its rich upholstering, was the envy of the townspeople—and this, be it remembered, was but one room of all the great house.

Surrounded by these marks of wealth and of power, Cantwell dropped into his great rocking-chair, while his negro valet, having lighted the candles in the sconces, brought out a velvet suit of garnet, lined with pea-green satin and touched here and there with silver embroidery. After this, Cantwell, whose dark eyes had followed his servant hither and thither about the room, called for wine and asked that he be left alone. Then, although it was close to the hour of supper, he lay back in his chair and gave himself over to deep thought.

Scarce thirty years had passed since John Cantwell's eyes had first opened at Lancaster, in England, and of those thirty years fourteen had been spent in North Carolina. Landing at New Bern in the spring of 1740, a long-limbed, keen-eyed boy of sixteen, he had made friends from his first day ashore; and as he made friends he made also money. At the end of his second year in America he had built up a considerable traffic with the Indians. Exchanging clothing and tawdry ornaments for rich furs and crude native implements

of war and of peace, he marketed his curious wares among the British mariners who came to port, deriving therefrom the just and equitable profit of eight hundred per cent. Then, by an astuteness that set agape the mouths of the good people of New Bern, Cantwell made thousands of guineas by his sales of stores and munitions of war, first to Oglethorpe, who fought the Spanish invasion, and later to the Canadians and their allies, at the siege of Lewisburg, in 1745.

It mattered little that some envious ones whispered that Cantwell's powder sold for louis d’ or and doubloons as well as for honest British sovereigns. The only thing of consequence was that Cantwell made the money; and by long strides he mounted to prosperity and ease. In his twenty-fifth year he bought the captured buccaneer El Escoria, changed her name to the Leopard, and placed her in the West Indian service, trading triangularly between New Bern, Havana and Liverpool.

It was after this that Cantwell, blessed with easy circumstances, abandoned his adventurous trading with the Indians and his long journeys with powder-trains and store-wagons, and settled down to an ever-widening sphere of influence in the home of his adoption. His friendships extended to the statesmen of the province and the favorites of the king. But this was done modestly, and with no show of undue exultation. Then, to keep his blood in tone and his muscles firm, he put to practical use the knowledge of surveying, which, through long study by lamplight and by firelight, he had gained in the years past. And throughout the province many disputed boundaries were set aright by

his skill. He was made justice of the peace in the town of New Bern, and still retained the office, although beyond real need of its fees: for John Cantwell, with some fifteen or twenty thousand pounds to the good, would still let nothing pass which would add a shilling to his store.

During the governorship of Gabriel Johnston, the influence of Cantwell became more marked than ever. He might at any time have held a seat in the council, yet firmly set aside the pleading of his friends, and kept aloof from the halls of legislation.

It was at this time that Cantwell accepted a limited commission from Governor Johnston. Acting under this, he began a journey along the shores of the Neuse, seeking a spot where a great English mill might locate and find water wherewith to turn its wheels. Out of all the province Cantwell was chosen for this mission, because he knew the river from Pamlico to the headwaters, and from shore to shore, and from its high-tide mark to the silt that drifted along its bottom. Then, too, all the tongues of the Indian tribes were to Cantwell as the king's own speech; and the governor wished to learn some other things that none but the Cherokees knew. Thus, Cantwell's quest was of importance; and when it degenerated into something not foreseen in the plan, the governor was not the one to blame.

All might have gone well, and Cantwell, possibly, would have lived a life of unbroken prosperity and ease, had it not been that the pestilence that walketh in darkness went far from its course and seized upon Cantwell in the noonday. Stricken with the marsh

fever that spread through tidewater Carolina in that year, he rode, ill and half crazed, through a rain-storm of many hours’ duration. At last, when the dusk had shut down over all the land, Cantwell halted at the lonely cabin of the Widow Ross, which stood then, and for twenty years thereafter, at the end of the mile-long path that ran crookedly westward from Neusioc.

She who opened the door to Cantwell's knock was Mary, the widow's daughter, a fair-haired girl of his own age, with eyes of violet and with red lips and peach-blow cheeks. Ill though the man was, a flash of eager interest crossed his face, and he addressed the girl in such soft-spoken phrases that the blood surged beneath the fair skin of her cheek and she lowered her gaze to the floor. A quick gleam came to his eyes. Then, looking across the room, with unhesitating frankness he met the widow's kind regard and named himself John Matthews, a traveler lost in the forest and ill unto desperation. Why he did it, whether the river-fever had mounted to his brain and had left him unreasoning, or whether something came to him of the things that might lie in the future, none but Cantwell could tell. At any rate, Matthews had he called himself, and as Matthews they took him into their home, giving him such welcome as their humble means afforded.

Seeing how ill the man was, they placed him in the best room in the cabin, which room happened to be Mary's, spotlessly swept and garnished. Then the girl, with tumult in her heart, sat half the night by the kitchen fire and wove romances, rose-hued and fantastic, with the dark-eyed youth as their hero.

They nursed Cantwell for nine long weeks. Before he left them he had learned all of their pitiful story of hardship and disappointment. He knew how Henry Ross, who for ten long years had fought the Indian and the wolf in that wilderness, met his death one day at even by the falling of a rotted pine beside his very cabin door; how the widow and the daughter and the twelve-year-old boy had struggled against the enemies that lurked in the forest and the destruction that came hand in hand with the wars of the elements.

Then, over and above all, was the pitiful hope against hope for the day when all these things would pass from them, and they might come back again to the settlements of peace and plenty. So he learned much of them; but they knew little of him, save that he found favor in their eyes; that he spoke with more than passing kindness to the girl; and that he had wealth and power beyond that of any man they had ever known.

Then came the workings of that inscrutable power which the brothers of Islam call kismet—that which to some is “fate,” and to others “Providence.”

Cantwell's visits to the cabin became frequent; and, as seemed befitting, he paid court to the widow's daughter; and through it all, there being none to gainsay him, he remained John Matthews.

At last, when springtime was close at hand, when the wood was fair with the sweet bay and the magnolia, and the yellow jessamine and the wild tulip bloomed in the forest groves — on one of these days, in the grass-girt path that wound along the river shore, Cantwell asked Mary to be his wife. And she, looking

into his face with awe, and trembling, said, “If mother place no bar in my way, I will wed you when you will.”

And that had been four years ago! The smile that came with the thought died on Cantwell's lips in a sneer. As Sequa had said, the woman was a fool!

Rising to his feet, with something very like an oath he consigned his memories to perdition and began dressing for the evening meal: for Mistress Cantwell, high-bred and high-strung, awaited him in the dining-room, and her temper when awry was not pleasant for a man to face. But Mistress Cantwell was not she who had once been Mary Ross.

Now, it goes without saying that the story of a man's life, as that life is known to the man himself, can be told by no one else. And, equally, it goes without saying that the man never tells it. From the first of men (and thousands of millions have since lived and died) down to the youngest among us now, certain things in every life have gone and will go as secrets to the tomb. Perhaps it is best that this is so; for, were all things known, some several thousand saints would have failed to rise above the ranks of men.

As for John Cantwell, the world for many years thought him one man when in his life he was another. In the later days, when the rest of mankind began to know him as he was, some of the wise men of that time said that Cantwell had two souls, one of good, the other of evil. Certainly he lived two lives; but if one were bad, and that were the true one, then was the other bad, or worse: for it was a lie. The hypocrite who bows his head in holy places has less grace than

the other sinner who flaunts his wickedness from the house-tops.

Yet, with Cantwell there were times — as one among his friends could say — when the man rose for a brief spell above the charnel-house of his dual self, and suffered in that moment such tortures as are measured to the unredeemed. Be that as it may, few knew until his last day that John Cantwell was other than the upright man of trade, the just magistrate, and the friend of the humble people. None was more eloquent in prayer, none more brotherly in sickness or in death, and none more willing to help whomsoever needed a friend. He who stopped a man in the streets of New Bern, and asked, “What know you of John Cantwell?” would straightway have his answer: “’Squire Cantwell is a good man—yea, and a true one.” Such was he in the eyes of the people. In the eyes of God — but that is not for man to say.

Well might these things have come to Cantwell's mind that night as he sat at his table. Facing him was Mistress Cantwell, stately and proud of soul; and at his left and at his right were the little son and daughter who had come of their union. Yet, in the forest, ten leagues to the west, was Mary Ross, wedded to him by the lawful ritual; and somewhere between the one wife and the other was Sequa, who looked upon him even as did the two others. But, with it all, Cantwell's face betrayed no sign save of peace and satisfaction of soul. That was the way of the man.

CHAPTER II The Theft of the First-BornAFTER her talk with Cantwell, two nights and a day and a fourth part of the second day passed before Sequa, emerging from the forest, entered the village of Neusioc. A full thirty miles had she come; and the journey had been a rough one. The road that joined Neusioc and New Bern could scarce be called a road. Cypress and scrub oak lined the way; and marshes and bayous so crossed the course that much of the highway lay a sodden mire for half the day and a flooded swamp in the hours when the tide was in. Through this country, with the wolf and the bear in wood and in canebrake, Sequa had made her solitary way. What wonder that at Neusioc she sought her father's hut and slept there until the close of the afternoon.

Neusioc, as has been said, stood at the eastern end of the path which led to the home of Mary Ross. How old the place was no one knew. When the first pale-face came up the Neuse, he found it an ancient Indian town—so ancient that its chief, himself blind and feeble with age, could but say that Neusioc was old and decaying when his father's grandfather led the war dance of the tribe that gave the town its name.

But Neusioc, in this twenty-seventh year of the

reign of the second George, was not as it had been in the days of its heathen king. Of the mouldering wigwam walls not one stick nor stone stood beside or upon another. Huts of log and sapling lined the town's single, crooked avenue; and here and there a gleam of red marked the rise of a white man's chimney. Fences, heavy with gourd vines, kept the cattle from the gardened yards; and from every homestead came the medley of the poultry and the swine. Indians were there, some clear-eyed and proud with the pride of race, but others, and the greater part, dull-faced and drink-besotted—broken reeds at the end of a line of kings.

Within the little settlement peace and harmony prevailed, white men and red working together as of one kind, each helping to ease the other's burden. And of the men who peopled the town, two stood head and shoulders above their fellows. They were James Noel, the village minister, and Tetah, the father of Sequa. Mr. Noel had a wife, frail and fair as a drooping flower, and a laughing, blue-eyed child; while Tetah, whose squaw slept beneath the sod of the Piedmont forests, had but the girl; yet she was one whose beauty made her greater in the province even than was he himself.

The Reverend James Noel had come from England to the Carolinas nearly a year before, and from his own purse had built the rude log church that stood on the little village green. Tetah had trodden the forests before Christopher Baron de Graafenreidt brought his Swiss and his Germans from the Alps and from the Rhine, when the century was but nine years old; and

Tetah had no church, for his god was the great Manitou, whose temple was the earth beneath and the sky above and all that lay between the two. The minister was the second son of a great peer, and his brother, ill in health and broken in spirit, was Henry, Lord Durham. With any day might come the death of Durham, and the stately mansion would open its doors to receive as its master the Carolina missionary. Tetah was the only son of a chief whose feathered crown had nodded at the downfall of legioned enemies. Back among the mountains lived a warrior tribe, whose squaws kept ever ready the lodge of him whose fathers were kings among their people back unto the days when the great sea lapped against the peak of Yuannocca; and that was very long ago, for now the mountain of the Manitou stands sheer three thousand feet above the plains that lie below.

Such were the two men, and, although God had made them of different races they were alike in so far as each of them was fearless, steadfast, and of unswerving truth.

From the time that Mr. Noel had come to Neusioc, Sequa had made it her way to stop at his house and ask his blessing whenever she passed through the village. Her father, who thought the white man's religion a good thing for some men and all women, had taught her this; and for a twelvemonth she had been unfailing in her duty. So it was with some wonder that the minister learned at evening that Sequa, after sleeping all day at her father's house, without further ado had gone back to the forest, passing the parsonage without a look to the right or to the left. The worthy

man thought a long while over the strangeness of Sequa's behavior, and at last came to think that something outside of love and lovers troubled the girl's mind.

Mr. Noel and his wife were at supper, and their little daughter, Alice, was sleeping in her crib, when the news came to them of the things which concerned Sequa. While they sat there, the knocker made a loud clangor on the front door. They heard the servant's step, the opening of the door, a rush of skirts, and a woman's quick sobbing in the hallway. A moment later, and Mary Ross, white-cheeked and wild-eyed, entered the dining-room. She gave them no time for greeting, but burst into a storm of grief.

“My child! my child!” she cried, as she staggered forward to the light. “Mr. Noel, where can he— Oh! help me.”

She stood for a moment, her hands pressed tightly on her breast and her eyes fixed with pitiful appeal upon the minister's face. And a fair picture she made, for the woman was comely, and her face was such as painters use for a Mater Dolorosa.

The minister and his wife had both risen to their feet when Mary entered the room; and he, fearing she would faint and fall, pushed aside his chair and crossed quickly to her side.

“Your child?” he said, sharply. “What is the matter?”

She suffered herself to be led to the sofa by the window. “Stolen,” she gasped; “stolen.”

Mrs. Noel gave a nervous little cry.

“Stolen?” repeated Noel. “By whom?”

“By an Indian girl — an hour ago. John was —”

“Never mind John now. Who was the girl?”

“Sequa,” she answered him.

Then he knew what had kept Sequa from the parsonage. He began pacing backward and forward.

“Now tell us how it happened. Begin at the first, and tell even the slightest circumstance,” he said, with the ring of kindness again in his voice.

She did as she was told. The story was a simple one. Mary's recital made it graphic, and her facts were unencumbered with supposition.

She had gone to the kitchen to prepare the evening meal for herself and her brother John. The babe she had left sitting on the floor encircled by his toys. Suddenly it came to her that the little fellow was quieter than was his wont. Stepping to the doorway she looked into her room. The child was gone. She ran to the outer door. John was hoeing in the field by the river. She tried to call. Her voice failed her. Then, from the edge of the forest she heard something like a laugh. Turning quickly she saw the graceful figure of an Indian girl sweeping down the path to the wood. She tried to follow her, but a deathly faintness came over her. A little sapling stood by the door-step, and she reached out for it to help her until the giddiness passed away. At the bending of the path the Indian girl looked back. The face was the face of Sequa. She was laughing, and held a bundle in her arms. Then the earth and woods and Sequa's bronzed face seemed to whirl about before her eyes. Myriad stars flashed before her, the ground under her feet rose up like a great black sea, and she felt herself falling,

falling, until her brother's voice awoke her. Then she was in her room and on her bed, with John binding her head in wet towels.

When she had finished her story, the minister, standing by the table, regarded her thoughtfully.

“Have you ever done anything to offend Sequa?” he asked, after a moment's silence.

She shook her head. “Never,” she answered.

“Or any of her friends, or people?”

“No.”

“Did John Matthews, your husband, ever speak of her?”

Mary affirmed that Matthews had never known the woman.

“Then,” he said, “you know of no reason for this act of hers?”

“Not the slightest.” The look of appeal was still in her eyes, and her lips trembled visibly.

Noel looked across at his wife.

“Alice,” he said, in his firm, quiet voice; “ask Henry to bring Tetah here.” Scarcely had the words left his lips when Henry stood in the doorway.

“Mars’ Noel,” the negro said, “the Injun Teeter says as he wants to see you.”

“Send him here.”

Then, with the shuffle of moccasined feet and the rattle of many beads, the chieftain entered the room. Giving a quick glance into the faces of the two women, he crossed to where the minister stood to meet him. With a gesture of greeting, the Indian spoke.

“You see Sequa?” he asked, in low, musical tones.

“No; she did not come,” responded Noel. Then,

closely watching the chieftain's face, “Do you know why?”

The strong, deep lines of Tetah's face showed no change from the look of truth which was stamped there.

“Sequa find trouble,” was his laconic answer.

Noel kept his eyes on the scarred features before him. “Trouble?” he asked. “What kind of trouble?”

“Tetah not know.”

“Has she been to your house?”

“Yes. Sleep all day.”

“Was she alone?”

The Indian nodded affirmatively.

“When did she go away?”

“When sun go.”

“And which way?”

“Up river.”

“Have you seen her since?”

“No.”

“Then why do you think she has met with trouble?”

“Sequa no eat good — no come see white chief — Peoperquinaiqua. Sequa trouble.”

Despite the seriousness of the matter in hand, Noel smiled at the force of the Indian's reasoning.

“Why have you come here?” he asked.

“Peoperquinaiqua good man — good heart, good head. Tell what trouble Sequa?”

Noel shook his head. “No,” he said, slowly. Then, after a moment's silence, “Go and find Sequa. I'll wait for you until midnight.”

Without more ado Tetah turned on his heel and left the room.

The minister took his seat by his wife. Mrs. Noel was the first to speak. “Why didn't you tell him that Sequa had stolen Mary's child?” she asked, with womanly resentment. Noel smiled.

“Tetah is an Indian: Sequa is his daughter,” he answered. “Had I told him all that we know, he would justify her course and we would lose an ally.”

“But if he finds her with the child?”

“He will bring her here, child and all.”

“And if he doesn't find her?”

“Some one else will.”

“But who?”

He turned his head slowly, looking first at his wife, then at Mary.

“That is a question,” he said, at last.

Mrs. Noel gave an impatient tap of her foot.

“James Noel, you are so provoking. Of course it's a question. Who will find her?”

Had Mary not been there, Noel's answer would have been, “Perhaps no one.” As it was, he looked earnestly into the white face which turned with its mute appeal to meet his answer.

“No mortal can tell you that,” he answered, kindly. “I will try; and Mary's brother can do much. Beyond that —” He paused a moment.

“Beyond that?” reminded Mrs. Noel.

He looked thoughtfully toward her.

“Beyond that,” he said, slowly — and the wheels of Fate were whirling fast as he spoke — “beyond that, I know of but two who can give us aid. One is Tetah, the other John Cantwell, of New Bern.”

“Cantwell?” repeated his wife, musingly. “Oh!

yes; ’Squire Cantwell; and he knows all about Indians, doesn't he?”

“Not all: no one can claim that. But he knows more than any man in the province, except, perhaps, the hunters who live among them.”

Mrs. Noel had crossed the room, and, sitting beside Mary, had slipped her hand into that of the broken-hearted woman.

“You will ask ’Squire Cantwell to help us?” she asked.

“I will write to him now. If Tetah comes back alone, Henry will start with the letter to the ’Squire.” Then, turning to Mary, “May God be good to you!” he said, a little huskily. “I feel your grief more than I can tell.”

Then he left them together, which was wise in him; for a man can give little comfort to a woman in bereavement, save when the tie of love is between them. But two women — that is a different matter; and Mrs. Noel, with the tact and resource of the highly-bred, brought comfort to Mary's heart, and hope into her night of trouble.

The hours passed with sullen, grudging slowness. In the study the letter to Cantwell was written and sealed for its sending. In the other room the minister's wife, in low tones and with tender words, was bringing some little cheer into Mary Ross's life. At last the time came. On the stroke of twelve the study door opened, and Noel entered the dining-room from one side as Henry and Tetah came in at the other.

The Indian stood like a bronze statue under the light of the hanging lamp. In breathless silence they

waited for him to speak; but he said nothing. Raising his eyes to the minister's face, he held out his open hands, palms upward and empty. The eloquence of the simple gesture was unmistakeable. He meant that he had sought Sequa and had failed to find her.

Mary, sobbing bitterly, sank back into her seat.

Tetah gave her one quick glance, then with stolid demeanor turned from them and left the house.

Thus it was that an hour later Henry, astride his master's horse, took the New Bern road, bearing Noel's plea to Cantwell. And Mary again took heart and looked to the morrow with a new hope, for she knew no Cantwell. Truly, the ’Squire had woven a devil's net, and the powers of darkness seemed to have labored with him.

CHAPTER III A Meeting and a PartingTHE home of the Noels was among the better looking houses in the village. It was strongly built, and within its walls were several rooms and a long passage-way from front to back. It stood upon a terraced knoll, and between it and the winding, unpaved street lay a grass plot, broad and smooth and of a cheering green. The house, though well constructed, was not a cool one, and for this reason Mr. Noel had erected on the lawn an arbor, now covered with vines; and he and his wife often sat there, for it was cool and shady and gave an unobstructed view of the river as it crept past the village and rounded the bend toward the sound.

The day after that on which Mary had lost her child was sultry and oppressive. It was late in the afternoon. Mary had returned to her woodland home, there to await news from ’Squire Cantwell, and the minister and his wife were spending an hour in the arbor while the baby Alice slept within the house. They had been talking of England, and of their life in the days before they came to America. After a brief silence, during which the minister, his mind far away from Carolina, stared with grave, unseeing eyes down the sweep of the Neuse, and his wife bent her fair young face over a

lapful of embroidery—Noel returned to their former theme.

“From all the talking that I do,” he said, turning away from the river and looking down at her, “one might think that I wanted to go back again; but I cannot say that I do. True, England is dear to me, but America is dearer, so long as you are here with me.”

She raised her head, and answered him with a smile of appreciation.

“We have sacrificed more than we would if we had stayed in the old home parish,” he continued, when she had returned to her needlework; “but I feel that the reward has been perfectly adequate. Still, with all our contentment, I am inclined to worry over one or two matters.”

She looked up again, and laughed with the same low, musical laugh that had won his heart years before. “Worry?” she said. “Why, James, you couldn't if you tried — really you couldn't.”

He shook his head. “You over-estimate my optimism, Elsie,” he said, with a smile; “but, seriously, my brother Henry has been ill for many months, and I fear that any ship may bring me news of his death.”

“Y-es,” was the doubtful response, “it may come; but men who are ill so long seldom die suddenly. You would have heard long since if Henry's illness had become serious.”

“Perhaps you are right.”

Then they relapsed into a silence, broken only by the faint sound of the thread drawn through the linen on Mrs. Noel's embroidery frame.

The minister sat leaning slightly forward, his chin

upon his hand and his eyes following the flight of a gull which soared above the river. Then his gaze dropped a little, and was fixed on a tiny speck in the middle of the broad sweep of the river. As the spot grew larger the minister's preoccupied look gave place to one of eager interest; and when the dot on the water's surface became an eight-oared gig with a gleam of the royal blue at its helm, he began to hum an old sea song, learned on the wharves of Hull in the days of his boyhood. His wife looked up at him.

“Why, James,” she said, in wonder at his change of mood, “how can one tell when you are serious and when gay? What have you done with your cares?”

He nodded toward the boat in the river. “Of his Majesty's navy,” he said, with gladness in his voice. “Perhaps some one we have seen before — at any rate, a real human being who can tell us of the world outside.”

They watched the boat draw nearer. It seemed a long time before the oarsmen reached the Neusioc shore; but when that time did come, the boat, with a quick half-turn, swung with gunwale to the landing, and a light, active form sprang upon the bank.

The minister and his wife, from their distant point of vantage, could see only the quick, imperative gestures which emphasized the officer's commands. Then he turned away from his men and was lost in the bushes that overhung the path to the parsonage.

Five minutes later the officer, emerging from the thicket that bordered the field opposite the Noel house, walked quickly across the intervening space. He reached the front gate, where Mr. Noel waited to give

him welcome. Taking him by the hand, the minister led him to the arbor.

“Elsie,” he said, with a boyish ring of gladness in his voice, “here is Lieutenant Maynard. But where is our fatted calf?”

Mrs. Noel arose and held out her hand. “We're very, very glad to see you again, Lieutenant; but do n't let Mr. Noel's allusion to the fatted calf lead you to believe that you are altogether a prodigal in our eyes.”

Maynard, bowing graciously, smiled at her laughing welcome.

“Even though I had wasted my substance in riotous living,” he said, “and would fain have eaten of the food of the swine, you know, Mrs. Noel, that I could not have been happier in meeting you and this reverend husband of yours than I am now. But, first, my dear Noel, let me give you a despatch from England. It should have been sent by a less busy boat. The Wasp has been forced to wing her way in great zigzags, here, there and everywhere, since that letter was handed me. Read it now, while I deliver a cargo of woman's messages to Mrs. Noel. My wife saw me for only an hour in New Bern this morning, but she told me enough news—for Mrs. Noel's ears, of course—to keep a man's tongue busy for a whole day.”

The minister stepped to one side to read the letter, while the lieutenant, taking his place beside Mrs. Noel, continued his conversation.

Maynard was a splendid type of the British naval officer of that day. Though tall and somewhat spare in build, his tightly-fitting uniform displayed a muscular

development suggesting the sinewy agility of a panther. His eyes flashed whenever he spoke, sometimes with a gleam of merriment, again with a blaze that more than one man had learned to fear. There were other times when the fire in those hazel depths was subdued into a tenderness that made women wonder whether or not the stories of this man's terrible deeds of war could be true. And such was the light that shone upon Mrs. Noel as Maynard told her, with a thrill of pride in his voice, of his wife and the baby Arthur, in the governor's town of New Bern, thirty miles down the river.

“Margaret thinks,” he was saying, “that the boy is the greatest prodigy of the eighteenth century; and I don't know but what he is. If he does all that his mother claims, he'll be a statesman before he outgrows his dresses. But where is his little fiancee, Alice? I thought to see her running about here cracking her dolls’ heads against the trees, and —”

“Why, Will Maynard, she's only eight months old!”

“Eight months? Well, Arthur has hardly a year and a half advantage of her, and he can run and jump and ride horseback, and—”

“What terrible men you sailors are! Ananias must have held a commission in the king's navy.”

Maynard laughed. “No, Mrs. Noel. Not only could Ananias prove an alibi, but remember that the record says that he gave up the ghost. An officer in his Majesty's service never gives up anything.”

“Hush!” whispered Mrs. Noel, with a gleam of laughter in her eyes. “Don't let James hear anything like that. He'd preach about it next Sunday.”

“On my honor, I'll keep clear of such entanglements. But where is the baby Alice? May I see her before I go? I'm here only for the hour, and must sail for England to-morrow.”

“So soon? Can't you stay the week out?”

Maynard shook his head.

“You are going to England?” Mr. Noel asked, suddenly, folding his letter and approaching them.

“My orders so read.”

“Very soon?”

“To-morrow.”

Mrs. Noel looked curiously at her husband. His face was a trifle pale. “What is it, James?” she asked anxiously. “Bad news?”

The minister smiled and rested his hand upon her shoulder. “Nothing so very serious, Elsie; but go now, and see why Alice is crying. The Lieutenant and I must talk over some business.”

The two men watched her as she crossed the lawn and entered the house. Then the minister turned quickly to his companion.

“I, too, am called to England.”

Maynard gave a low exclamation. “You are?” he said, gravely. “I'm sorry. Can't you —”

“No, I must go. My brother Henry, Lord Durham, is so ill that he may die before I can reach Lincolnshire. In any event, I must be there as soon as possible. Can you take me on the Wasp?”

“Certainly, if you can get ready in time — say in an hour. Family going with you?”

“No; impossible. But if I do not return within two or three months, they must follow. In the

meantime, they will be safe enough here, although it will be terribly lonely.”

“It will, indeed. But you can arrange for Mrs. Noel to stay with Mrs. Maynard during your absence. It would be a godsend to my wife, for she, poor woman, is doomed to more than her share of that sort of privation.”

“Thank you, Maynard. You have anticipated my wish. She will need some little time to make her own plans; but I accept your invitation with what may be unseemly haste. Elsie, I know, will be delighted with the arrangement. Here she comes now.”

The whole world knows that women are not alike in their way of hearing bad news. Some meet the shock with a gasp that ends in a flood of tears and complete collapse of all that goes to the making of the nervous system. Others turn a little white, smile through the faintest possible mist of tears, then with Spartan courage face the trouble stout-heartedly and with unbending resolve. Of the latter kind was Mrs. Noel.

But an hour before feeling secure, even in that wilderness, with her husband to stand between her and the rough world about them, she was now brought to face months of separation, with danger lurking on every side: for the Indians had not yet learned the respect due a white man's home and kind, and what was now a peaceful, thriving hamlet might at any hour flow with blood and echo with the war-whoop and gun-shot of a horde of savage enemies.

Yet, when Noel told her that Maynard's ship was come to bear him away to England, she made no

murmur of complaint, but looked him fairly in the face and asked if he would be very long away. Then Maynard went down to his boat while the two made ready for Mr. Noel's departure, and formed hasty plans for the time when the minister should be in England.

Returning an hour later, the lieutenant met them at their door. “Before we go,” he said, cheerily, “can I not see the little girl?”

Mrs. Noel's face, despite its marks of tears, was wreathed in smiles. “Indeed you shall,” she exclaimed, leading the way to the house. “You'll find her waiting for you.”

They entered the room together. In a canopied crib in one corner of the apartment, lay the child. Her great blue eyes were open, and fixed themselves upon Maynard as the three bent over the crib. Mrs. Noel took her in her arms.

“Look at this great tall man, Alice. He's little Arthur's father, and little Arthur, you know, is going to be a great big man like this one is, and you are going to be his wife. Are you glad?”

The baby's mouth opened in a droll, childish laugh, and she stretched out her chubby arms to Maynard.

“That settles it,” laughed Maynard. “She can hear the wedding bells now.” Then after a few words of the flattery which women love—although they say not—the lieutenant led the way from the house.

Together they went down the path, Maynard walking ahead, and after him the minister and his wife, trying each to cheer the other. The ship's gig, guided by a stout sailor named McFaddin, came from

behind a clump of willows and lay alongside the landing. The lieutenant and Mr. Noel stepped aboard, the oars dipped into the stream, and the journey was begun.

Mrs. Noel stood on the bank and watched the boat until it swept around the bend; while the minister, looking back toward the little village, saw standing on the shore the frail woman whose sweet face and lovelit eyes as they then looked were fixed in his mind through all the years that came after.

Alone she stood there, a slight figure clad in creamy white. She gave one last look down the bare expanse of water, and a sob rose in her throat as she cried out into the solitude, “Oh! James, when shall I see you again?” In her frenzied fancy she thought that she heard an answer. Startled, she turned and looked up. A white-throated kingfisher darted past her with a hoarse cry. She shuddered, for the sound was an ill-omened one and the bird seemed to laugh in her face.

CHAPTER IV Consuming Flames

IN after days, when the man's deeds were known to the world, the people of New Bern wondered greatly that John Cantwell had for more than a score of years stood in their eyes a type of the upright man. And, viewing his life in the light of his deeds, strange indeed does it seem that his cloak had never fallen from him. True, some had seen what lay behind the veil of his great deceit, but these were silent for many years; and two, who knew quite as much as any of the others, never spoke save in the after-evidence which mortal power could not control.

Deeply laid were Cantwell's plots, and no one man, or woman either, knew a tenth part of them all. Yet their very mystery, and the perfect ease with which they passed on to success, made the weakest link in the chain of circumstance that brought the after ruin. And, with it all, twice—yea, thrice—did he plot beyond his own great reach. Had it not been for this over-stepping he would have died as he had lived, honored and respected by all except those—few in number as the fingers of a man's one hand—who knew the fellow for what he was.

As on a playhouse stage the paint and the sham

seem naught but the veriest truth, so in Cantwell's life did everything which the ingenuity of a devil's craft could work to that end proclaim to the world virtues which were but an empty show hung upon a fabric of treachery and falsehood.

Nowhere was the man's machinery of hypocrisy more glaring than in the office-room in which he handled his West Indian trade and voiced the thunderings of the law. Upon its walls were hung prints from the masters, of The Crucifixion, The Temptation, The Death of Ananias and Sapphira, and Daniel in the Lions’ Den. Besides these, in gilded frames, were the Ten Commandments, with illuminated border, and a chart exhibiting some man's notion of a Christian's path to heaven; which last must have had its irony in Cantwell's mind. Then, over the desk at which the ’Squire was wont to write his bills, his briefs, and his sermons, were three framed mottoes, blazoned in great letters of crimson and gold: “Waste Not, Want Not,” “Everything in its Time,” and “Honesty is the Best Policy.” The first two were well enough; but the third—well, Cantwell kept it as a man listens to an adversary's argument, because he took no stock in it.

The morning was half gone. Cantwell, seated at his desk, seemed awaiting a visitor.

Although he sat very quietly, scanning with more than casual interest the pages of a bulky work on chemistry, his eyes were often raised to the window that opened toward the street, and several times within the half hour had he looked at his watch and frowned. He was waiting, and impatient; yet when a knock

sounded upon the door he gave a sudden sta and half arose from his seat. Then he smiled and sank back into the chair. The knock was repeated.

“Come in,” called Cantwell.

The door was opened by a servant. “Mrs. Maynard,” was the announcement. The ’Squire rose, and moved toward the door. His visitor, superb and queenly in mien and dress, met him at the entrance.

“My dear cousin,” exclaimed Cantwell, with open admiration in his restless eyes, “you excel even yourself this morning. I feel amply repaid for the hour I have waited.”

Mrs. Maynard laughed lightly as releasing her hand from his over-ardent grasp she crossed to a chair by the window. “An hour, you say! Well, forgive me; my little Belgian clock is dropping backward in the race. But, really, I —”

“No, no, no; the delay caused me no inconvenience, be assured of that.” The ’Squire, with a stately bow, returned to a seat at his desk. “The lieutenant sailed yesterday, I saw; and the worthy Mr. Noel, also. God speed them both.”

Mrs. Maynard nodded her acknowledgment. Her woman's discernment had caught the indifference which lay beneath the ’Squire's fair-spoken phrases, and she wasted no words in replying.

The ’Squire smiled urbanely.

“And little Arthur — how is he?”

“But slightly better. The medicine you gave the other day seems to make the little fellow drowsy and dull. Did you intend that it should?”

’Squire Cantwell's face was averted as he bent

over his desk to sharpen a quill. After a moment he looked up.

“Well — hardly,” was his slow response, “but there are conditions, particularly in so young a patient, when almost any medicine would cause some degree of lethargy. But there is really no cause for anxiety.”

“You think, then, that the child is not seriously ill?”

“Seriously! Indeed, no. Were he so, I should send you to Doctor Boggs. The boy is doing well, very well indeed.”

Cantwell smiled blandly as he voiced his opinion, for he took pride in his knowledge of nostrums. Then he leaned forward with his elbows on the desk.

“Now, Margaret,” he said, with a certain business-like brusqueness, “you told me you had some papers to be examined—something of a legal nature, as I understand.”

Mrs. Maynard took a small bundle of documents from her hand-bag.

“Yes,” she said, “my husband advised me to have you register these papers, if you thought it necessary to give them legal force. One of them, I believe, may be of personal interest to you.”

’Squire Cantwell took the documents and rapidly read them through. Mrs. Maynard, as she watched him, could well have been the model for a painter's masterpiece. The rich harmony of the deep brown of her eyes and the raven blackness of her hair with the rose of her cheeks and the vivid blood-red of her lips would have made her singularly beautiful, even had her features been less striking than they were. That great statesman, Governor Gabriel Johnston, had said

that Margaret Dudley Maynard was the loveliest woman in the American provinces; whereat Lord Keightley, scanning her classic features and meeting the look of her great dark eyes, had said, “Your Excellency means the loveliest woman in the universe.” And the old lord seldom spoke praise of any woman.

At last Cantwell laid the papers aside and looked up at the lieutenant's wife.

“This last paper does interest me,” he said, slowly, tapping with his long index finger the back of an elaborately engrossed deed; “but only upon your account and that of your husband. The interest of remainder vesting in me rests upon a contingency that probably will not occur. Your possession, cousin, is almost absolute.”

“But if my son should die before reaching the age of twelve?”

“In that case the property, at your death, might revert to me or my heirs. But in the first place, your little Arthur is not likely to die within the next ten years; children under such circumstances seldom do. And then, if you will notice, the language of this conveyance is, that if you have no son who shall reach the age of twelve years, then, and then only, shall ‘all the goods and chattels, real and personal, herein above described, be conveyed to John M. Cantwell’; and so forth. It does not say that this particular son must be twelve years of age, but a son, any son; and remember, Margaret, that you are practically at the beginning of what may be a long married life; there might be —”

“Yes,” interrupted Mrs. Maynard, lowering her eyes, “there might; but still ‘a son’ may prove to be

this son only.” A smile crossed the face of the justice.

“That remains to be seen. But,” and he dropped the documents into a desk drawer, “you have not told me, cousin, why this brother, Richard Dudley, did not leave you his property without conditions.”

“He and my husband had some misunderstanding, the work, perhaps, of a secret enemy.” In her earnestness, she raised her eyes to his. The ’Squire's face was expressionless as marble.

“But, passing over that,” she continued, quickly; “the papers will require registration?”

“Undoubtedly. I will have it done to-day. Now,” and he arose from his chair and came toward her, “is there anything else you wish done?”

“Yes. I want a good safe boat with two trustworthy men, the day after to-morrow. I'm going up to Neusioc to bring down Mrs. Noel, the minister's wife. Our husbands have gone away together and we think it only fair that we, too, should join forces; so I've asked her to come down to spend a month with me. You can get me the boat?”

“To be sure. I'll send McFaddin and another good man.”

“McFaddin? I thought he belonged to the Wasp.”

“He did up to the hour she sailed. His time expired, and I've hired him for the Leopard.”

“Ah, yes. And you're sure the boat won't leak? I'm — But, quick! Who is that?” She and Cantwell, rising hastily, reached the window at the same time.

“That?” The ’Squire laughed. “A young squaw with a papoose strapped to her back. No unusual —”

“Go after her — send some one to see if the child isn't white.” She spoke excitedly. “Please, John, send some one. I'll — I'll explain afterward.”

The ’Squire flushed as she used his Christian name. He opened the door quickly.

“McFaddin! McFaddin!” he called.

“Aye, aye, sir,” sounded a gruff voice in the hall.

Cantwell stepped outside the door. A whispered conversation followed, and the ’Squire, returning, sat down beside his visitor.

“He has gone,” he said, briefly.

“Thank you, very much. I want to know because my husband and Mr. Noel brought a boy down from Neusioc yesterday. He was searching for an Indian woman who had stolen his sister's child. I thought the girl who passed here might be the one.”

Cantwell's mask-like face seemed whiter than ever. “What was the boy's name?” he asked, looking down as he played with his watch-charm.

“John Ross.”

“Is he here yet?” Cantwell asked, quickly.

“No, I think not.”

“Who is his sister?”

“Mary Ross — Matthews, rather; for she married some worthless fellow, who afterward deserted her.”

“Ah, yes. I recall the case. An unprincipled rascal, this Matthews. I met him once. But who is the Indian girl?” He raised his head, and their eyes met.

“Sequa, a Neusioc.”

The ’Squire's glance wavered a little, and a quick flush rose to his temples.

“Sequa,” he repeated, musingly. “I do not know the woman.” But something in his manner belied his words, and Mrs. Maynard's eyes flashed with a sudden surprise.

When he spoke again it was upon another subject.

“While we wait for McFaddin, have you no other business to discuss?”

“Yes, and I nearly forgot it, too. I need some money, Mr. Agent, quite a little sum. After Mrs. Noel comes down here, she and Madame DeVere and I are going to Wilmington for a pleasure trip. I am the instigator of the plot, and all expenses will be mine. So, money, good ’Squire! Money!” She laughed as she held out her hand.

“How much, cousin? Times are close, you know, and rents hard.”

“Now, now, ’Squire! don't stint, or you'll make me find another agent. Calvin Brown paid you a quarter's rent yesterday. Come!” And she shook her hand with mock impatience. The ’Squire, fairly beaten, gave a low chuckle.

“Tell me when to stop,” he said, taking a roll of bills from his pocket, and counting them one by one into her outstretched palm. She spoke when Cantwell had but two bills left.

“Thank you, truly. Keep the rest until the next time.”

Cantwell smiled dryly. “May it be far distant, cousin. You are —”

A great shouting came from outside the house.

“Fire!” sounded a hoarse voice in the street.

“Fire! Fire!” echoed a dozen others.

Cantwell rushed through the hall to the front door.

“Where?” he shouted.

“Lieutenant Maynard's,” came the answer.

An anguished cry came from the parlor. “Oh! my child. My child! Can't you save him?”

Hatless, the ’Squire dashed down the steps and darted up the street. The alarm had been long delayed. When he reached the house it was a mass of raging flame. Cantwell broke through the crowd. Some one called him.

“Too slow, ’Squire; we've got the furniture — all exceptin’ one room.”

“Which room?” thundered the ’Squire.

“The south one,” was the answer.

Cantwell was deadly pale. Mrs. Maynard, breathless and sobbing, pushed through to his side.

“My child!” she moaned. “Where is he?”

The men looked stupidly at one another. One hysterical woman screamed. A tall negro with a bloody rag about his head elbowed his way to the front.

“Whar be yer boy, Missis?”

“In the south room.”

The black shook his head.

“Stairs is done broke, Missis; I went down wid ’em.”

She seemed not to hear him.

“Is there no hope?” she asked, with slow utterance, like one speaking in a dream.

Cantwell pointed to the terrible furnace before them.

The answer was plain. From what had been the

south wing the flames leaped in a roaring, twisting column fifty feet above the walls.

If Margaret Maynard saw Cantwell's gesture or heard the words of the throng about her, she made no sign. Silent, motionless, she stood there, as senseless as a statue carved in marble; and upon her lips lingered a faint, dreamy smile. So it was that they who saw her knew that somewhere behind that pure white forehead a little vein or a tiny nerve had ceased its working; and that the woman knew naught of the world that moved about her.

Out on the wide Atlantic, hugging the coast toward the shoals of Hatteras, reeled the Wasp under full sail. Her commander, leaning on the after-rail, watching the sea as it rolled away in their wake, was thinking of his wife and their baby Arthur.

“How happy we'd all be,” he said softly, to himself, “if I could walk in on them now — God bless them both!”

He looked, smiling, toward the hazy shore lines of the Old North Province. But he was a hundred miles too far away to see the pillar of smoke and fire that writhed angrily above the little town of New Bern.

CHAPTER V Some Further Tricks of Fate

THE morning of the following day dawned bright and clear. The road that led from New Bern to the Pamlico shores stretched broad and level beneath its vista of towering interbranching cypress trees, its white length touched here and there by a gleam of ruddy gold as the sunlight pierced the leafy maze above and played upon the sands of the travelled way.

The sun had climbed but an hour high when ’Squire Cantwell, on a chestnut mare of Eastern breeding, rode slowly up the highway toward the old town. Where he had been at such an early hour did not appear, nor did it in any way affect the things which happened afterward. What played a part, however, in the forming of the great web which was of the ’Squire's spinning, was the point toward which his mettled steed was now bearing him; for that point was the house of McFaddin, who, a few days before, a sailor on the Wasp, had left his Majesty's service to enter that of Cantwell. It was this man's house which now sheltered the child that Sequa had tried to carry to Cantwell. This explains why the ’Squire was making his way toward the sailor's home. It also makes clear the presence of McFaddin himself, trudging

along the road beside the rider's stirrup. The two men were talking; and quiet though the roadway was, Cantwell had to bend often over his saddlebow to catch the utterances of the over-cautious sailor.

As they neared a little log-cabin that stood a short way from the roadside, Cantwell leaned again toward his fellow-traveller: “And so you have the child?” he asked — although he knew as well as did the man himself.

The sailor raised his black eyes to Cantwell's face. “Yes, yer honor,” he answered, smiling, as he shifted his tobacco in his cheek.

“Where?”

“At the house with the old woman.”

“Boy or girl?”

“Boy, yer honor.”

“Describe him to me.”

“He's all rig'lar an’ ship-shape, yer honor; ’most too much sail fer the ballast, maybe; but more ’n that I don't see nothin’ pertic'lar. He jes’ cries, that's all. He'd drownd the bo's’n's whistle in a sou'west gale. ’Pears old enough to talk; but we can't git nothin’ out'n him but ‘Mama! Want mama!’ an’ sich stuff.”

“What did the squaw say about him?”

“Did n't wait to say nothin’. When she saw me overhaulin’ her she drapped the baby, blanket an’ all, an’ steered fer the woods.”

“You've done well; but I'm in doubt yet: I must see the child, McFaddin.”

“Easy ’nough, yer honor. There's my cabin, a ship's length up the road; an’ there's the old ’oman lookin’

out o’ the winder. Jes’ heave me yer bowline an’ I'll make fast to a tree while ye git down.”

Reaching the cabin and fastening the horse, Cantwell, dismounting, followed McFaddin into his humble abode.

“Hi, Peggy!” thundered the sailor; “here's the ’Squire come to see the little un’.”

McFaddin's wife, stout, brawny and sunburned, held out a calloused hand to Cantwell. As he spoke his graceful words of greeting his keen eyes saw that the woman's face was a good one, strong and kind and motherly. He asked to see the child; and the sailor's wife led him to the bed-room, where the baby lay sleeping on a couch, by his open hand a wooden spoon, his plaything in his waking hours. The ’Squire bent down and studied the little round face. Then he shook his head and murmured something under his breath.

“Know him, sir?” asked the foster-mother.

“No, Peggy; but I think he's the child that some of my friends are looking for. Keep him here until I find out. In the meantime, you must have something for the expense of taking care of him. I don't know that I'll ever get it back; but you know, Peggy, we must be kind to the unfortunate if we hope to get on in the world.”

“That's so, yer honor; an’ for my part, I think this here's a case in p'int. A poor innercent thing, stole from his nat'ral mother by a low-down Injun squaw as tried to make a dirty papoose of ’im. I hates ’em, sir — them Injuns. I hates ’em ’cause they're red; an’ I hates ’em ’cause they grease their ha'r — hates ’em fer nigh onto ev'rythin’. But as you say, yer

honor, bein’ we're poor, it would go sorter hard with us to care fer the little thing fer somebody as is better placed than us; an’ all fer nothin’, too. Hows'ever, I'd ’a’ done it, pay or no pay.”

“Spoken like a Christian woman, Peggy.”

The ’Squire smiled upon her with benign complacency.

“Nothing is lost by good actions. Bread cast upon the waters will return again, you know. Now, my good woman, here is some money. When it's gone, call upon me for more. But, hark you, Peggy, and you, too, McFaddin, keep all this business to yourselves; and, above all, never mention my name in connection with it. I do not care to become a subject of common talk.”

“No more do I, yer honor,” protested Peggy, her face reddening under its coat of tan. “But when the neighbors comes in —”

“They must n't come in, Peggy — at least, not yet. I have my reasons, which I cannot tell you now. So, for the present, not a word of it, or —”

“You can depend on us, yer honor,” McFaddin interrupted. “Peggy's all right.”

“But —” started Peggy, looking from one man to the other.

“But me no buts, old ’oman. You know yer all right, ’specially when I says it. Tell the ’Squire so.”

“Of course, I —”

“That'll do. I knowed you'd say so, Peggy.”

Cantwell watched them closely. Then, moving to the door, he said, with a smile of satisfaction, “We're agreed now; I will come again to-morrow.”

McFaddin followed him to the roadside. Cantwell uttered some trifling jest, and the two men parted with laughter, the ’Squire turning his horse's head toward New Bern.

True to his word, Cantwell returned at noon of the next day. Seated upon a log out of ear-shot of the cabin, he and McFaddin talked for an hour; but the look upon the sailor's face betrayed dissatisfaction, and the rigid set of the ’Squire's jaw showed, in turn, the stubbornness of his determination.

McFaddin was speaking. “I don't like it — with all respeck to yer honor. Ef so be as you wants me to board a Frencher, or, fer that matter, a Britisher — fer it's all the same to me ef the shiners is there — I'm squar’ on hand. That's fightin’ ’g'inst men. But babies — that's another kind o’ game.”

“But the child's in my way, McFaddin.”

“That ain't no concern o’ mine. Ef it's the baby o’ that gal up the river, she's give it up ’fore now. Her brother's gone back, and that's goin’ to be the last of it. Let the old woman keep him. He'll be a kind o’ comfort-like, when I'm a-cruisin’.”

“Too many prying eyes and busy tongues around us, McFaddin,” protested Cantwell. Then, with ill-disguised impatience, “but manage the details your own way. Lose the brat, or send him off so far he'll never come back. Remember, work this right and you ship as mate when the Leopard sails again.”

“Aye, yer honor; and thanky. I'll do my best to deserve yer compliment. But this here bus'ness — well, give me time. I'll fix it if I can.”

“I prefer to be served promptly. Take your time,

but be sparing of it. Now, let's go in and try your wife's persimmon beer. By the way, do you keep your secrets from her?”

“When I can. Peggy's mighty peart at findin’ things out; but we've got her guessin’ now. Fearin’ accidents, I won't tell her, neither. But Peggy's all right.”

Mrs. McFaddin, her face a little flushed, met them at the door.

“Bring out yer home-made beer, Peggy, dear?” said the sailor. “The ’Squire wants to see the color of it.”

She did as she was bidden, and the jug and the glasses made merry music for several minutes; then the ’Squire, taking some spices from his waistcoat pocket, placed a pinch in his mouth. “Well, Peggy, may I see the two-year-old?”

“Certain, sir,” was the answer, as the old woman led the way into the bed-room. “But he's sick, yer honor; got a fever, I'm afeerd. No wonder, neither; don't see why he didn't die, trudged about the country a-steamin’ in that ’ere blanket fer I don't know how many days, an’ nothin’ to eat but Injun swill. But, hush ye! He's sleepin’ now.”

The Good Samaritan, bending over the luckless wayfarer on the road that led to Jericho, could not have looked with kindlier eyes upon the stranger whom he befriended than did ’Squire Cantwell, the pious justice of New Bern, upon the little child on Peggy's bed. Stooping down, he felt the baby's pulse.

“Why yes, Peggy; the child has a burning fever. We must stop that. I'll ride down this afternoon with

some powders for him. Poor little fellow! I wish I had the medicine now.”

His voice seemed to betray great concern, and he hurried away without stopping for an exchange of adieus.

The sound of his horse's hoofs had hardly died in the distance when Peggy turned abruptly to her husband.

“Bob,” she asked, sharply, “whose child is this?”

“Blast my peepers ef I can guess, Peg.”

“Whose do you think?”

“I don't think. I've gi'n it up.”

“Oh! Bob McFaddin. Can't you tell nothin’ to yer wife? But I'll call in Poll Johnson; it'll take more'n me to watch this ’ere baby.”

“Call nobody. You told the ’Squire you wouldn't.”

“There's where yer wrong. You promised, not me.”

“Didn't you say, ‘Of course,’ when we squeezed you up in a corner? Certain you did, an’ you've got to stick to it — stick to it like a man, ef you know what that means.”

“Ef I've got to keep it from other folks, I won't have it kept from me. Tell me the hull thing, or I'll blow.”

“Blow an’ be da — well, jest blow. I told you all I know about the thing.”

“But I heerd you talkin’, Bob.”

“The devil an’ Tom Walker! What did you hear?”

“I didn't hear nothin’ ’bout no Tom Walker; but as to the other feller — I come pretty close to seein’ him and hearin’ ’im, too.”

“Now, be sens'ble, old woman; what did you hear?”

“You know what he said about pryin’ eyes an’ busy tongues?”

“Did you hear that?”

“Never mind, Bobby. An’ yer goin’ to be mate on the Leopard?”

“Blast it! you heard the hull thing.”

“An’ yer goin’ to lose the youngster, be you?”

“Oh! say —”

“Or send him clean away, eh?”

“Oh! the — thunder! I mean. Come, I'll shut yer mouth by givin’ you the hull story.”

Thus did Peggy learn the ’Squire's plot against the child which she had already learned to love. For several hours afterward her eyes gleamed ominously, and she muttered strange things to herself as she worked about the house.

When the ’Squire came at four o'clock in the afternoon, Peggy, radiant with smiles, met him at the door.

Cantwell greeted her cheerily. “My good woman, how fresh and young you look! How is the little boy? Still feverish? Too bad, too bad. Well, we must cure him for the sake of his mother, whoever she may be. Here are the powders. Start them about bedtime. One will be enough to-night; give the rest at hourly intervals to-morrow.”

Peggy followed the instructions to the letter; but when the following day had nearly passed the child was still very ill. At sunset of this second day the ’Squire came again.

“I begin to feel interested in the little fellow,” he said, by way of introduction. “I think he is some better; but he is threatened with tetanus — lockjaw, you know. There, don't wake him, but give him another powder when he wakes from his nap.”

“The powders is gone,” Peggy responded; “used the last one two hours ago.”

“True; I forgot. Let's see; I think I've got some more in my pocket; if — I — have n't — ah! yes here is another dose. Give him that.”

As he handed the blue paper to Peggy, the watchful woman saw that the ’Squire's hand trembled, and that his eyes avoided hers.

An hour later the child awoke, moaning piteously. Peggy gave him a drink of water. Then she took the paper of powder and crossing to the window stood looking reflectively down the road. “Bob,” she said, at last. “Ef the gal up the river's this child's mother, who's his daddy?”

“The ’Squire knows; it's out o’ my jurydiction.”

“What'll you bet ’tain't the ’Squire hisself?”

McFaddin stood up with a jerk; a sudden light came into his eyes. “Peggy,” he said, in an awed whisper, “I'll be durned ef I don't think yer right.”

Peggy was silent a moment, looking down at the blue-wrapped medicine.

“Bob,” she said, finally, “The ’Squire give me this ’ere powder for the baby. I ain't goin’ to try it on him.”

“Why not? Didn't the others go all right?”

“Yes, but this is diff'rent.”

“Who'll you try it on? Not on me, ef I knows myself.”

“Take it out and give it to Bowzer, that nasty dog o’ your'n.”

Bob, pulling nervously at his black side-whiskers, took the paper gingerly in his fingers and went out of the kitchen door. It was nearly a quarter of an hour before he returned; and when he entered the room his face was grey with horror.

“Ef there's a God in heaven,” the sailor blurted out, “he ought to take that ’ere ’Squire by the neck an’ beat ’im till he's dead.”

“Did yer dog eat the powder?” asked Peggy, breathlessly.

“Did he? Well, I jes’ reckon.”

“What did it do?”

McFaddin raised his eyes. “What did it do! What did it do!” he shrieked. “It knocked Bowzer so stiff — oh! my Lord; I never —”

“But what did it do? Is Bowzer dead?”

“Dead? Yes, dead and gone to — no, jes’ dead.”

The couple sat for a long time in silence; then Peggy came to the fore with a masterpiece of ingenuity.

When the good ’Squire came to the McFaddin's house at sundown the next day, Bob, with solemn demeanor, met him and led the way to the bed-room. Peggy, her face buried in her handkerchief, sat beside something that, long and box-shaped, lay across a chair and was covered with a spotless sheet. The ’Squire gave a nervous start, and spoke with a great effort.

“I hope the child is better,” he said, in a voice that sounded strange even to himself. Peggy looked up into his face. “He is dead,” she said, simply. Cantwell