TheHOMEWARD TRAILWALDRON BAILY

NORTH CAROLINIANA COLLECTION B.W.C. ROBERTS

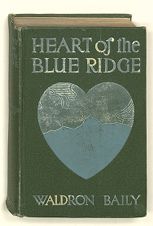

Bookplate

THE HOMEWARD TRAIL

He noted as never before the slender grace of her form

with its lithe erectness

Publisher cipher decorationNEW YORKGROSSET & DUNLAP PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY

W. J. WATT & COMPANY

THE HOMEWARD TRAIL

THE HOMEWARD TRAIL

CHAPTER IDAVID, sitting under an apple tree, stared with vague eyes toward the thicket of dogwood that bordered on the far side of the orchard. Then, of a sudden, his gaze quickened as there came a movement of the foliage, and a fawn stepped daintily out into the open, where it stood placidly regarding the young man with limpid, friendly eyes. One ear stood out at a right angle from the head; the other was laid back, attentive to something within the thicket. David knew that this something must be Ruth, with whom her fawn wandered everywhere. He stood up expectantly. A moment later, the girl issued from the shelter, and at sight of the youth stopped short beside the fawn, which muzzled her hand in a gentle caress.

For a little, the boy and the girl were silent, studying each other with intentness, in which was something partly admiration, partly surprise, as if they saw with a new clarity of vision. It was borne in on David with startling abruptness that his childish playfellow of years was a child no longer, was indeed a woman grown, and, too, beautiful. He noted as never before the slender graces of her form with its lithe erectness. His glances roved half-shyly over the delicate contours of the oval face, and he saw that she was very fair. He had known it before, but not as he knew it now in this flash of illumination. An unfamiliar beauty was revealed to him here and now in the red lips curving so tenderly, in the satiny purity of the complexion with its petals of rose in the cheeks and the trace of brown given by the sun, in the aureole of hair that was itself like sunlight, in the lucent blue eyes, which shone with mingled mirth and pride and affection.

Ruth, for her part, in her contemplation of David recognized something unfamiliar. She did not quite understand its significance, but she felt herself half-confusedly abashed by its presence. She sensed dully that her

boyish companion, as if in the twinkling of an eye, had become of a man's full stature. The thought subtly distressed her, even while it gratified her. So she thrust the idea out of her mind in order that she might greet him again to-day as yesterday.

“Oh, Dave!” she called. There was a warm note beneath the gayety that rang in her tones. “Just think of pappy's trusting you to do all that business for him! I reckon he never let anybody else collect money for him.” She laughed as she added: “You know pappy's mighty particular about his money.”

David grinned in response.

“Yes, there ain't no two ways about his being almighty close. He sure does make the eagle squawk plumb awful every time he pinches a dollar. I cal'late I'm some proud over his sendin’ me with that load of apples.”

“It means you're grown up, Dave,” Ruth answered, and there was a hint of wistfulness in the music of her voice. Then, because she herself by no means understood the full significance of her words, she went forward quickly with the fawn at her side. When

she came to where the young man stood, she paused, and put her hands to his cheeks, and, as he bowed his head toward her, lifted her face, and put her lips to his. In the same second, she drew away from him, and her cheeks flamed as they had never flamed before from the kisses she had given him. She stood mute and motionless, with downcast eyes, in a trouble half-shamed, half-sweet.

David, too, stood wordless in a great confusion. The kiss had loosed in him a flood of emotion that thrilled and bewildered. It was as if consciousness were drowned in the tide of feeling. And as in the case of a drowning man the whole life passes in review during a few seconds, so now before the mind of David a scroll was unrolled. But this panorama showed only the kisses of Ruth. They had been frank, free kisses all, some tender, some mischievous, always kindly. For, as to this young man and woman, each was an only child, and, since they lived on adjoining farms, they had always been playfellows. David remembered the day of his first great grief, when from a field whither he had gone to weep alone over the mother

who lay dying, he had seen his father come out of the house and pass down the road toward the village. A great desolation had fallen on him, for the man bore, according to local custom, the measuring stick, which he had cut to the length of his wife's form, and which he would now carry to the carpenter to serve as a measure for the coffin. So the boy had known that his mother was dead. Ruth had come to him in the misery of that hour, had comforted him with her kisses. Again, within the year, when his father went to fight in the Confederate cause, leaving the son in charge of William Swaim, Ruth's father, the girl had welcomed him to his new home with kisses, and had cheered him in his loneliness. When, on his return from a hunting trip with his father in the Blue Ridge Mountains, along the upper reaches of the Yadkin River, he brought her, according to a promise made, a fawn which he had caught, she had showered on him glad kisses of gratitude. There had been other kisses innumerable—joyous, teasing, tender. Here was one of a sort altogether different. In it was something disturbing, something curiously penetrating and potent. It was a

mystery to this boy who did not yet realize his manhood.

The rough voice of Swaim broke the spell that held the two.

“Drat thet-thar dumned pesky deer t’ Tophet! Ye left the corn-crib door open, Dave, consarn ye! An’ the ornery critter has done et nigh a full peck o’ seed corn, an’ thet seed corn's wuth money, by cripes!” The old man glared accusingly in turn at David and Ruth and the fawn, which had slipped away to a little distance as if in conscious acknowledgment of its guilt. David, though aware that he was not at fault in the matter, forbore any attempt at defense, for he had no wish at this time to provoke further his penurious and irascible task-master. Ruth, however, boldly resented this flouting of her pet.

“You ought to be ashamed of yourself, pappy,” she declared spiritedly, “to begrudge a darling little thing like Mollie a few ears of your old corn. And,” she added impudently, “likely you left the door open yourself. Dave is a sight more careful than you are, pappy, and you know it.”

The father drew his shaggy gray brows

in a fierce scowl, which the daughter bore undaunted. His voice came with a rasp.

“Git inter the house, Miss High-an’-Mighty, an’ help maw with the bakin’ an’ sweepin’ an’ sich-like women's tricks, instid o’ lally-gaggin’ round hyar a-wastin’ yer own time an’ Dave's.”

The scarlet flooded Ruth's cheeks once again at this direct attack, and she retreated in haste, the fawn following. The old farmer turned his frown on David, whom he regarded grimly for a long time. He was a hard man and uncouth. He had a reputation for meanness throughout the community, and it was deserved. In his fashion, doubtless, he loved both his wife and daughter, but they suffered none the less from his penuriousness. His parsimony fretted Mrs. Swaim more than it might have most of the neighboring wives, there among the foothills of the Blue Ridge, in North Carolina, for she was of better birth than her husband, and had even received the advantages of a course in the female seminary at Salem. In her romantic girlhood, her fancy had been caught by the handsome and virile mountaineer. She had been speedily disillusioned. Her

single compensation was in Ruth, and for her daughter's sake, she had held herself from falling into the slovenly ways and illiterate speech of the community. So, too, she had trained her child as best she knew how in matters of deportment and manner of speaking. William Swaim had no sympathy for any such “ ’tarnal foolishness.” He demonstrated the fact now by his aspect as he stood glowering at the young man. He was barefooted, and shirt and overalls hung loosely on the tall, thin form. In the deep hollow between the outstanding neck muscles, the huge Adam's apple jumped spasmodically, as he chewed his quid of tobacco, and either spat or swallowed the juice. The face was thin and drawn, brown and wrinkled. The beak-like nose hinted of cruelty and avarice. The sparse gray hair and the tangle of whitening beard were unkempt and frowsy. The eyes were pale and watery, with reddened lids. They were blinking now as he contemplated David with a malevolent distrust, which found expression in his next words.

“Hit's powerful resky trustin’ business t’ a harum-scarum galoot what hain't got sense

enough t’ lock wanderin’ wild beasts outen the corn-crib.” David opened his mouth to protest, but thought better of it, and permitted the slur to pass unrebuked. “They'll be quite some money a-comin’ fer thet-thar load o’ limber-twig apples. I'm puttin’ right smart o’ confidence in you-all, David, an’ I dunno as I had orter ’a’ done hit. As I said, it's resky—pizen resky.” Having thus relieved his saturnine humor, Swaim became almost cheerful, and spoke alertly. “Time we got busy with the load, t’ git hit done come night, so's ye kin start at sun-up t’-morrer.”

David followed obediently, even with huge satisfaction. For this commission given him by Swaim to sell the apples in Salisbury, though seemingly such a trifling thing, was in truth a matter of serious importance to those chiefly concerned. To the elder man, the sending forth of the youth was in the nature of a test. David's father and he had been friends as well as neighbors. Naturally enough, by reason of their mutual liking, and, too, by reason of the fact that their farms adjoined, and that each had an only child, they had planned a marriage between their

children. With more discretion than parents in such cases usually display, they had kept the project secret from those most concerned. Swaim had much liking for the lad, which, however, he was at pains to conceal. His decision to entrust David with the sale of the apples would never have been reached, had he not felt that it was a duty he owed himself to try out the business ability of his daughter's prospective husband. So, to him, a bit of petty marketing carried deep significance.

To David (and to Ruth as well) the matter was serious because it brought to the young man the first real responsibility in his life, and the fact marked his stepping across the threshold that separates boyhood from maturity. A trivial event truly in the judgment of those more sophisticated. Yet, to these primitive folk, the occasion marked an epoch. For that matter, this undertaking apparently so simple was destined to prove the beginning of vital episodes in the lives of David Simmons and Ruth Swaim.

CHAPTER IIBEFORE dawn the following morning, David had thrown the harness on the tassel-tails, as he called the mules, and hitched them to the canvas-hooded wagon laden with apples. A blast of the horn summoned him to the breakfast which Ruth had prepared and now served to him. But there was still constraint between the two, and their words were few and perfunctory. David seemed to give his entire attention to the meal before him, and thus left Ruth free covertly to study the clean-cut features of the young man, framed by the waving black hair. She considered for the first time, with a maidenly wonder that was almost awe and wholly admiration, the breadth of his shoulders, the depth of his chest, the slim waist and tapering flanks. It was only when at last he arose from the table with a sigh of repletion that David's black eyes met Ruth's in a long, intent, questioning gaze. Presently,

the girl's glance wavered and fell, and the color mantled her cheeks. David felt a thrill of exaltation, though he could not in the least understand why.

“I wish you luck, Dave,” Ruth said. Her voice was very low, faltering a little. “I'm sure you'll make a good job of it.” But she did not offer him a kiss, nor did he ask it.

“Do the best I can,” he replied, and hurried out.

Within a minute, he was seated on the driver's seat under the shelter of the projecting canvas top, and, with a savage crack of the long-lashed mule-whip, was off. Craning back for a last look, he saw Ruth in the doorway, who waved her hand to him, and he waved in return. Then, with a great contentment in his heart, he settled himself to the long drive. Though David was too familiar with his surroundings to be deeply stirred by them, nevertheless the beauty of the scene harmonized with his mood, and served to emphasize it. His eyes scanned with pleasure the luxurious tints that the autumn had painted on the foliage of dogwood and oak and sweet-gum. A bob-white called from a thicket, and David whistled a

Then, with a great contentment in his heart, he settledhimself to the long drive

response. He listened, without any futile thought of imitating, to the soft and exquisite singing of a mocking bird hidden within the wood. There was no drawback to his satisfaction as he journeyed on. The fall rains had held off, so that the roads were good, and he made excellent progress. Other wagons, similarly loaded, swung into the highway from cross-roads, until David found himself one of a caravan moving leisurely within a cloud of thick, red dust. The song of birds, the murmur of brooks, the rustling of leaves beneath the light wind were overborne by a riot of coarser sounds—the thudding of mules’ hoofs on the hard clay, the clanking of harness chains, the creaking of heavy wagons, the bawled oaths of drivers, the hisses and crackling reports of whip-lashes; at the fords, the noise of churned waters, the snorting of the beasts, the raucous laughter and shouted conversations of the teamsters.

At nightfall, the train halted and made camp. David, after he had attended to the mules, fried his bacon and eggs over the common fire. Then he rolled himself in his blanket on the ground beneath the wagon, and fell asleep to the lullaby of strenuously

strummed banjos that came from the boisterous group still gathered around the fire.

The strangeness of his situation caused David to awake long before the first glimmerings of light. In his eagerness to accomplish the task set him, he at once began his preparations for the road, since he could see clearly enough by the starlight. He had fed the mules, and breakfasted, and started off before anyone else in the camp was stirring. So, it came about that in mid-forenoon he swung the mules on the easterly stretch of the route to Salisbury.

It was as he came close to his destination that for the first time his spirit lost its buoyancy. There before him, on a tract of the rising ground between the town and the river, loomed grimly the high stockade of the Confederate prison. At first glimpse of it, David's thoughts flew to his father, who had been captured, and now languished in some place like this far to the north, under guard of Union soldiers. David had heard much concerning the sufferings of the captives here in Salisbury prison, and, as he pitied them, he was filled with dire forebodings over the fate of his father. Where the road passed

alongside the high stockade, the ground sloped sharply upward, so that from his perch on the wagon seat, he was above the level of the stockade's top, and could look down and behold every detail of the gruesome spectacle within the barrier. David pulled the mules to a standstill, and stared at the scene, fascinated and appalled.

The acres of the inclosure were crowded with a tatterdemalion horde. These men were gaunt starvelings, the wretched, famine-stricken victims of war's cruelty. They were clad in soiled rags of uniform, which flapped grotesquely loose on the emaciated bodies. Through the masks of bushy whiskers showed pallid features, lighted by cavernous eyes. Some were so weakened by privations that they were shivering even in the full warmth of the sunlight. On many, the bandages were witness of wounds still unhealed. Often an arm was lacking; often a leg.

One of those mutilated in the latter fashion first drew David's particular attention, for the cripple stood near the stockade, looking up toward him. He was a young man of about David's age, who, under a happier fate, would just now have been in his prime.

Like David, too, he was tall and straight, with massive shoulders and a mighty chest. The prisoner's natural attributes of strength made more conspicuous the pathos of his present condition with wan, drawn face and haggard eyes and stooped form hunched on the support of the crutches. One trouser leg dangled empty from the knee.

A sudden livelier gust of wind caught the unfastened canvas curtain on the side of the wagon toward the stockade. The cloth was lifted and thrown back over the framework, so that the heaped apples showed plainly above the side of the box. At sight of them, the cripple's famished face lighted with a consuming desire. After the scant rations of sour corn bread which had been practically his only food for many a weary day, the ruddy richness of the fruit was torture to his need. He cried out shrilly in a voice that quivered from the intensity of his longing.

“Hi, mister! Can't ye spare one of your apples to a poor cuss, who's just about starvin’?” The smile that went with the drawling words was pitiful.

The look in the fellow's eyes pierced David

to the soul. The thought of his father in desperate need like this moved him to generous action. He reached quickly over the back of the seat, picked up an apple, and tossed it over the stockade toward the cripple's eagerly outstretched hands.

The intended kindness was of no avail. Another of the prisoners, who was standing near at hand, had been watching greedily. He, like all others in that place, was ragged and forlorn and obviously very hungry. He was a short, wiry individual of mature age, with the chevrons of a sergeant still showing on his coat-sleeves. A bristling red stubble of beard gave him an appearance of fierceness. Now, as the apple flew through the air toward the cripple, he whirled and sprang with surprising agility. He caught the apple, and bit into it avidly almost before his feet touched the ground. Then he sauntered off, shamefaced, but munching voraciously.

The cries of indignation that had broken from David and the cripple simultaneously caused the other prisoners near by to look in the direction of the sounds. A single glimpse of the apples set them hurrying toward the stockade, calling out in supplication. At

first, however, David gave no heed to these others. His heart was hot with wrath against the red-whiskered thief who had so meanly despoiled the cripple of his gift. Nevertheless, the remedy was simple. He plucked another apple from the load and tossed it over the stockade. His hasty aim fell a little short. The man on the crutches lurched forward clumsily—too late. A wobegone, tottering relic was suddenly galvanized into life, and pounced upon the spoil. The cripple rested inert, an expression of hopeless misery on his face. David felt a new pang of grief for this sufferer whom as yet he had failed to comfort. He was hot with wrath against those who had thwarted him. Then, in another second, as his ears took in the pleadings of the men massing at the stockade, his anger died and gave place to a new and broader sympathy for these stricken ones. Yet, he was by no means unmindful of the first to win his interest. He was indeed more than ever determined to accomplish his purpose. To that end, he resorted to strategy. He seized a double handful of the apples, and tossed them to either side of the cripple. While the soldiers scrambled for these, he

sent over two others so nicely directed that the cripple easily caught both in his cap. This success delighted David, and his delight was made deeper by the joy that shone in the man's face as he looked up and smiled.

A warm tide of benevolence welled high in the young mountaineer's bosom. He forgot that these men here before him were his enemies. He remembered only their need. Their piteous appeals moved him to a reckless impulse of charity. He no longer thought of the business entrusted to him by William Swaim. His sole concern was to assuage to the full measure of his ability the urgent necessity of these famished prisoners. A philanthropic zeal drove him on. He clambered over the seat and stood among the apples, and threw the canvas side-flap up over the framework of the top. Then, without any hesitation, he began casting the apples over the stockade. The forlorn captives surged toward the barrier, yelling their glee over the precious food that rained on them like manna from heaven. David hurled his kindly projectiles from both hands, fast and furiously. The crowd within the yard swirled hither and yon, following the flight

of the apples. They chattered and cursed and laughed in an abandon of fantastic happiness over this break in the horrible routine of their imprisonment. David exulted with them.

Some boys, going a-fishing, halted by the wagon to stare round-eyed at the strange spectacle of this young man with the handsome face and flashing eyes and long black hair flying in the wind, who was throwing these great, luscious apples so wildly over the stockade, from behind which sounded the roaring acclamations of the mob.

“Say, give us some, suh!” one of the boys shouted.

David heard the treble cry, and answered it.

“Come on up here, an’ fill your pockets, an’ help me throw,” he commanded.

On the instant, the boys swarmed about him, first filled their pockets, and then gave themselves merrily to this new sport of bombarding the enemy. The many nimble hands made short work of discharging the cargo. A hail of apples filled the air. There was joyous rioting among the prisoners, who just before had been so apathetic in their wretchedness.

Now, they were suddenly bubbling over with liveliness, romping and chuckling and gloating—and munching. The boys working beside David squealed gibes at their foes, and strove to catch them unawares with apples cunningly aimed. David threw no less fiercely, though with no malicious intent. On the contrary, he was all aflame with the lust of giving. It was with sharp regret that he saw the last apple fly over the palisade. He gave a glance down at the empty wagonbox, and sighed. He made a gesture of dismissal to the boys. As they clambered down from the wagon, David faced the mass of prisoners within the enclosure. He swung his hands, palms out, in a wide gesture.

“They're all gone, boys!” he called. The note of sorrow in his voice was unmistakable.

For a few seconds, a tense silence rested on the ragamuffin recipients of his bounty. But, in another moment, the grateful men broke into cheers that grew in volume, became a thunderous din of thanksgiving. The pæan of praise was a wonderful music in the ears of David—a music that reached to his heart, and melted it. The tears of a pure happiness misted his eyes. He nodded stiffly

in acknowledgment of the cheers, and then in great confusion climbed to his seat, gathered up the reins, and, with a crack of the whip, set the mules jogging.

CHAPTER IIITHE whirl of emotion continued without change until, with a shock of surprise, David looked about him and realized that he was in the Salisbury main street. He pulled the mules to a halt mechanically, but did not move from his place. A swift revulsion of feeling battered down his complacent mood, and left him the prey of misgivings which increased in intensity from moment to moment. At last, his consciousness awoke to the nature of his act in yielding to a heedless impulse. He perceived that by the impetuousness of his conduct where he had meant only kindness to those in want he had actually inflicted wrong on the man who trusted him. It was with a feeling of blank despair that he admitted the truth concerning his deed. He had given with noble generosity. Unfortunately, the gifts were not his to bestow. The supplies for his charity had been stolen from William Swaim. That no theft had been intended made no

difference. The ugly fact remained. The glow of satisfaction was gone now. In its stead came a chill of apprehension. He shivered with dread of what the outcome might be.

David slumped in his seat, and groaned. His dismay was abject. But he made a mighty effort to regain some degree of courage in the face of the disaster he had so unwittingly wrought. He reflected that at least the issue need not be faced for many hours yet, since there remained a long drive homeward. He was sure, with dismal foreboding, that he would be unable to sleep the coming night. There would be time a plenty for consideration and decision as to his course while he lay rolled in his blanket beneath the stars.

Since he had no business in town, thanks to his kindly folly, David turned the mules, and started back drearily along the way over which he had come with such high hopes. As he passed the stockade, he held his eyes studiously averted from the scene of his undoing. But, when he encountered the caravan which he had left behind, he played the hypocrite, and bragged shamelessly in answer

to questions concerning the quickness with which he had disposed of his load.

“God rid of ’em in a jiffy!” he announced quite truthfully. But the triumphant smile that accompanied the words was a lie.

Melancholy drove with David across the miles. His brain grew weary and then numb in the effort to devise some means of relief from the difficulty of his position. The little money left with him by his father had been spent. Though Swaim had made him earn a man's wages, there had been no contract to pay them, and there was no slightest likelihood that the old man meant to expend any money unless compelled to do so. Could he have paid the market value of the apples, the arrangement of the matter would have been simple. He might have been jeered at for the sentimental absurdity of his performance, but that would have been the worst result. There would have been no question of dishonor. But he had thrown away the property of another, while without power to make good his fault by purchase. Yes, he was undoubtedly a thief. William Swaim would not hesitate to call him just that—a thief!

His forebodings were justified, for that night David did not sleep. Again and again, he went over the event of the morning with increasing bitterness against himself. But, in the course of his unhappy musings, he at last seized on a diversion from his own self-condemnation. It was as he chanced to remember the little, red-whiskered man whose greedy selfishness had interfered at the outset when the first apple was thrown, and had thus been the actual cause of the catastrophe that followed. David's spirit was filled with exceeding bitterness at thought of the man. The feeling increased in intensity until it was very near hate. It comforted him in some degree to charge another with the blame.

An inquisitive opossum came cautiously nosing. David threw a pine knot, and sent the intruder scurrying away. It was just as the first dull gray of the coming dawn lightened the purple black above the eastern hills. And it was in this moment that an inspiration came to David. He smiled grimly to himself in the darkness. The device he had hit upon was palpably flimsy. He was well aware that it by no means met the requirements

of his case. The sole merit of the idea was that it afforded a possible, though by no means plausible, pretext for self-justification. Still greatly troubled, but somewhat consoled by the fact that he had a defensive plea in readiness, David breakfasted, and hurried the mules onward. And now, curiously enough, as the distance shortened, he found himself thinking less and less of Swaim's condemnation, and more and more of what Ruth might feel over this thing that he had done. Once again, too, he found himself brooding over those tremors provoked in him by Ruth's last kiss. He tasted a flavor in the remembrance. His pulse quickened, with a tingling in the blood. A flush showed through the tan of his cheeks. His eyes deepened and glowed. And, notwithstanding all this, he did not quite understand the emotion that held him enthralled.

It was still early morning, for he had sent the mules forward at a smart pace, when David swung into the Swaim farmyard. Ruth was busy at the milking, squatting on her heels, using one hand only on the teats and holding the tin cup in the other, according to the custom of the neighborhood. Hearing

the rattling of the wagon, she hurried to the stable door, and waved a hand in greeting. Then, as she saw her father come out of the barn, she retreated, for she was not minded to have any witness to her next interview with David.

The old man's cadaverous face was contorted to lines of jubilation. His welcome was unqualifiedly genial.

“Wall, Dave, I didn't ’low t’ see ye afore sundown, an’ mos’ likely not till atter breakfast t’-morrer. Ye sure must be some kin t’ lightnin’. Them mules don't look like they'd turned a har.” As David threw down the reins and alighted from the wagon, Swaim, with a grin of anticipation, stepped close, and extended his right hand, palm up, in readiness to receive his money returns from the trip.

“Thar must be a right smart o’ call fer my kind o’ limber twigs in Salisbury these days,” he cackled in high glee. “Ye'd better fix t’ load up an’ go right thar ag'in whilst the folks is buyin’ so lively-like.”

David held himself resolutely erect, and spoke with an assumption of boldness that he was far from feeling.

“Why, Mr. Swaim,” he said, in a tone as casual as he could muster, “I got back so quick ’cause I didn't have t’ take the apples clean through t’ Salisbury. I found a customer on the rise o’ the hill where they keep the Yankees that all look so powerful hungry.” He forced a smile. “The feller what bought the apples stood right there in the schooner an’ done tossed the last of ’em right smack over that-there punchin fence while those poor devils scrambled an’ fit t’ git holt onto one.” A flash of reminiscent enthusiasm made his face radiant. “I tell ye, Mr. Swaim, it was wuth twice the wuth o’ the load to see how much good they did them starvin’ humans. The feller what bought ’em just couldn't he'p it, ’cause his heart was teched by sufferin’.” David gulped, hesitated for an instant, then added firmly: “That feller was me. I hain't nary cent t’ pay ye fer ’em. If ye won't wait till pap gits home ag'in, I'll hunt a job t’ work it out.”

William Swaim's jaw sagged, and he gaped for a few seconds at the young man, dumb from sheer amazement over this revelation. Then, presently, as his mind took in

the full enormity of David's offense, his face grew ashen, and he trembled. His miserly soul was wrenched by the loss of those dollars he had hoped to fondle. An uncontrollable wrath mounted against the lad who had thus betrayed him. His watery, red-rimmed, blinking eyes cleared suddenly and flamed. He strode a step forward, and lifted a clenched fist.

“Take thet, ye damn’ thief!” he screamed. His voice came shrill, cracked with rage, as he struck out blindly.

David guarded himself against the attack, but made no offensive movement in return. He was in the full of his strength, while the elder man was old for his years, and by no means strong. The youth had no fear of suffering any serious injury from the vicious assault, and so limited himself to defensive measures in which he was successful enough. He had no wish to aggravate his fault by thrashing the man he had already injured so dolorously in the pocketbook. Moreover, he could not forget that William Swaim was the father of Ruth, and as such necessarily immune from violence at his hands.

Ruth, having just finished her milking, heard

her father's shouted words, and echoed them with a stifled shriek of alarm. She dropped the cup of milk, and raced toward the barn. She was just in time to see her father, more than ever infuriated by his failure to break down David's guard, turn and leap to a pitchfork lying on the barn floor. Armed with this dangerous weapon, he again faced David. Ruth knew well the peril of the moment, for she was aware that her father possessed a temper which, though usually controlled, was when unleashed a madness that knew no bounds. The pitchfork was almost at her breast when she hurled herself between the two men, and cried out wildly to her father to stop.

William Swaim halted, a dazed expression on his face at the unexpectedness of the girl's intervention.

“Oh, pap,” Ruth gasped, “ain't you ashamed of acting like that with Dave—Dave been so kind and helpful to us all!”

The old man was checked, but the wrath still flared. He retorted with such haste that the words came stammeringly.

“He'pful!” he sneered. “He's a thief—thet's

what he is. He done stole my apples, my limber twigs what meant real money fer me. An’ he's wuss nor a thief—he's a fool, plumb daffy, fer he says he done fed ’em t’ the Yank’ pris'ners down t’ Salisbury. But I don't swaller no sech lie like thet-thar. Nary thief kin stuff Bill Swaim thet-away s'long's he loves the lady on the dollar.”

The outbreak of speech had served as a safety-valve for Swaim's fury. David realized that the father would not assault him further in the daughter's presence. For the time being at least, the crisis was past. He put his hands on Ruth's shoulders, and swung her about to face him. Even in this moment of stress, he noted with a thrill of new delight the loveliness of her flushed face, the splendor of the violet eyes that met his so steadfastly and so loyally. Then his lips twisted to a whimsical smile, and he spoke in a tone half of raillery, half of seriousness.

“I'm plumb guilty, Ruth,” he declared. “I'm jest that-there fool what your pap spoke of. But I done stole the apples t’ feed starvin’ humans—not fer love o’ the lady on the dollar.”

“Tell me!” Ruth urged. Both she and David had forgotten William Swaim, who lowered the pitchfork until the prongs touched the ground, and then stood leaning on the handle, staring malevolently at the young man.

David told his story with great earnestness. He suddenly felt that the most important thing in the world was to make Ruth understand exactly what had occurred. Nothing else mattered if only he could retain her good opinion. To this end he recounted his adventure in detail from the first blowing back of the canvas flap by the wind through all the incidents to the final scene with her father. And through it all Ruth listened breathlessly, at the outset astounded by the extraordinary happening, soon sympathetic, and finally happy over his generous impulse.

Swaim, too, listened. Somehow, greatly to his surprise, he felt his anger passing. He forgot in part his sorely wounded avarice. Now that he had sustained the first shock to his greed, he gave ear to the narrative with a curious mingling of emotions. Against his will, he was compelled to a feeling of

admiration for this lad who had robbed him in a fit of extravagant generosity. Moreover, he was ashamed now that he had let his temper so master him. He was horror-struck at thought of what he might have done, had Ruth not interposed between him and his mad desire. Remorse gnawed at his heart. Lest he reveal the softening of his spirit, he stealthily moved away, and passed out of sight behind the barn.

Ruth and David took no note of Swaim's departure. They were absorbed in each other, and in the story the young man told.

As he ended, the girl exclaimed in praise:

“Oh, it was splendid of you, Dave! I love you for it!”

There was no thought now of the embarrassment created between them by that last kiss in the orchard. She threw her arms around David's neck, and, with the ease of old habit, lifted her mouth to his, and kissed him.

Even in the act, recollection came to her, and the blood flooded her cheeks. She would have drawn back, but it was too late; their lips were already joined. And at the contact she felt a vibrant joy that eddied in

every atom. Thought ceased. There was only an exquisite rapture that pervaded all her being. Her senses seemed to fail. But nothing mattered—only the bliss singing in her heart. David's arms were like bands of steel about her, holding her close, so close! as if he would never let her go. And she had no wish save to be held thus always. His lips lay on hers like a flame that thrilled through the flesh to warm and gladden the soul.

For David understood at last the mystery that had so baffled him. In that second when she threw herself before him to save him from her father's frenzy his heart had leaped in an emotion deeper and sweeter and nobler by far than gratitude. He recognized that emotion for what it was—the love of a woman, concerning which hitherto he had only guessed crudely. The very intimacy through all the years of adolescence between him and Ruth had served to prevent his thinking of her as other than a sister, a comrade. Now, however, he knew her for the concrete verity of vaguely tender reveries. She was the one woman. He held her crushed to his bosom, and his lips were

eager. He was exultant, masterful in the joy of possession. He loved her, and he knew that she loved him. Her lips told him that in silence. Nothing else in the universe mattered at all.

CHAPTER IVAFTER a long interval, the lovers drew apart. They glanced about them with a guilty air, and were relieved that no one was observing them. They were both very happy, but, too, after the period of abandonment, they were now a little confused and embarrassed toward each other, made self-conscious by the bigness of this thing that had developed in their lives with such amazing suddenness.

It was David who first returned to prosaic thought. His gaze chanced to fall on the empty wagon. The sight of it brought back to memory the evil fashion in which Swaim had reviled him as a thief. The radiance of his face vanished. In its place came a somber darkening. His eyes hardened, and his lips set in lines of grim determination.

“I've gotter git out,” he said curtly to Ruth, who stared at him in astonishment over the abrupt change in his manner. His

voice was gentle, but held a stern note of resolve.

“Why, what do you mean, Dave?” the girl asked anxiously.

“I must git out o’ here t’-night,” was the answer. “I'm goin’ somewhere t’ earn a bit o’ money fer a bill I'm owin’ t’ William Swaim.”

“No, no!” Ruth remonstrated. Her heart sickened at the thought that she must lose this lover whom she had only just found.

David shook his head obstinately, and the firmly modeled chin was thrust forward a little.

“There's no two ways about it,” he declared. “It will be powerful hard t’ leave ye, Ruth, just after we've got t’ be sweethearts, but it can't be helped. I can't thrash yer pap, Ruth—jest ’cause he's an old man, an’ cause he's yer pap. An’ if I can't lick him, why, I just naturally gotter pay him fer them apples.” His face lightened a little as he smiled wryly. “T’ pay him I got t’ git money, an’ t’ git money I got t’ git out o’ here.”

“I know pap better than you do, Dave,” Ruth argued. She was eager to change his

decision, even though an instinct told her that her hope was in vain. “Pappy has an awful temper, and he's pretty close. He just flew off the handle, and didn't know what he was doing. He's all over his mad by now, and mighty ashamed of himself. And, anyhow, he knows you're good for the money. ’Tisn't as if your father was poor.”

David shook his head once again.

“My pap's money ain't any help, ’cause there's no way fer me t’ git hold of any of it till he comes back from that-there prison up North. Ye see, Ruth, I ain't hankerin’ t’ ’company none with Bill Swaim till I pay him an’ prove I ain't the damn’ thief what he called me.” There was a tone of finality in the utterance, which the girl recognized. She yielded to it, though bitterly reluctant.

“When will you go, Dave?” she inquired, almost timidly.

“Sometime in the night,” David replied; “like a thief should.” He disregarded Ruth's protest. “An’ don't ye breathe a word about it t’ yer pap er yer mammy.”

“But if I told pappy, he might—” Ruth began.

David interrupted her.

“Not a word t’ yer pap, Ruth,” he commanded. The girl yielded, though somewhat grudgingly.

“I suppose I must do as you say,” she pouted. “Wherever do you ’low to go, Dave?” There was a tremor of curiosity in her voice, and she added pleadingly: “Oh, don't go far away, dear!”

The young man regarded her with great tenderness.

“Not a mite further than I have t’,” he declared. “I ain't noways pinin’ t’ be shet o’ ye, Ruth. An’ ye can bet that I'll come back a-runnin’ the first chance I git.”

The conversation ended in new caresses between the lovers, which left them palpitating with happiness, the more intense because it had for a background the shadow of a parting so soon to come.

Throughout his work that day, David's brain was teeming with contradictory plans concerning the direction his journey should take. He decided after long consideration that his best hope of speedy success with the undertaking would lie in following the Yadkin River down to Georgetown in South Carolina, where in all probability employment

might be found. Or perhaps he might strike across inland from Georgetown to Charleston, on the coast, where the opportunity would be still greater.

No words were passed between David and Swaim at meals. Mrs. Swaim, whose delicate face showed the ravages wrought by the sorrows of an uncongenial marriage, betrayed by her nervous manner that she knew of what had occurred between the two men, but neither she nor her daughter made any reference to David's trip to Salisbury or its unfortunate outcome. After supper Ruth found an opportunity to speak alone with David in the orchard where he had gone to smoke his pipe.

“You're really going to-night?” she queried, when they had kissed each other.

“Yes,” David answered simply. He explained to her his purpose of going down the river in his skiff. “I'll slip away as soon as the old folks are asleep,” he concluded.

“I'll make you a package of provisions,” the girl promised. There came a ripple of laughter. “Pappy won't know. Mammy will, but she won't mind. She'll be glad.”

The girl was serious again now. “Mammy likes you, Dave.”

The lover was a bit confused by this indirect praise. He spoke sheepishly, but with sincerity.

“Yer mammy's a fine woman.”

But Ruth, though usually a dutiful daughter and affectionate, was not now interested in her mother's excellence. Her whole interest was absorbed by this being who had been her playfellow and intimate companion for years, yet to-day was revealed to her as a stranger—the lover whom she adored and whom, because he was her lover, she did not feel that she knew at all. The mystery of the new relation fascinated her. And by so much as there was charm in the present relation by so much there was grief at thought of the coming separation.

“I'll bring the package of rations down to the boat,” she said. “I'll have it ready for you by ten o'clock.” She regarded him accusingly as if she had subconsciously detected in his mind some idea of evasion. “Don't you dare to go before I get there.”

And David assured her that he would not, and ratified the pledge with many kisses.

They were not night-owls in the Swaim household. By nine o'clock all had gone to bed—ostensibly. As a matter of fact, Swaim and his wife had duly retired, and had almost immediately fallen asleep. David and Ruth, however, were wide-awake. On going to his room after supper, the young man at once busied himself with the modest preparations for departure. It was indeed a simple matter to pack in his carpet-bag the few articles of a very limited wardrobe. When his preparations had been completed, he sat down by the window, and comforted himself with a pipe while awaiting the lapse of time sufficient to insure sound sleep on the part of the elder Swaims. Finally he struck a match and saw by the flare that his watch marked almost ten o'clock. Carrying his shoes in one hand, and the carpet-bag in the other, with his rifle in the crook of the arm, he crept out of the room in his stockinged feet, and made his way with as little noise as possible over the board flooring that creaked alarmingly under his weight, past the bedroom door through which sounded William Swaim's raucous snores and the softer breathing of the woman, and on down the

stairs. He entered the lean-to kitchen, and felt his way through the darkness to the pantry door, which stood ajar. He whispered Ruth's name. There was no answer, and he guessed that the girl had finished her task already, and had gone on before him down to the river. He was confirmed in this belief, when, after recrossing the kitchen, he found the back door standing half-open. Sure that he would find her waiting for him by the boat, he went out into the night.

After the dense dark within the house, the night seemed well lighted with starlight streaming from the cloudless heavens and the golden glory of the hunter's moon. The tension under which David had been acting was suddenly relaxed as he felt the spell of the night's serenity. The hush of an infinite peace encompassed him, and for a long minute, he stood motionless, yielding to the charm of it. A tang of autumn chill was in the air. The young man filled his lungs with a deep breath, which at once soothed and stimulated him. Then, abruptly, his thoughts veered to the girl who waited for his coming by the river. Now, as he looked on the still splendors of the night, he saw them as

the fit setting for the loveliness of Ruth. Instantly, he was impatient to be with her, and set off running lightly down the lane that led to the river. He covered the quarter of a mile quickly. As he drew near where the skiff was moored, the girl caught a glimpse of him.

“Dave?” she called questioningly. There was a hint of anxiety underlying the music in the soft utterance, which David, in his happier mood, missed altogether.

“Supplies all stored aboard, eh?” he questioned in his turn, by way of answer.

Ruth tried rather unsuccessfully to meet his gayety in kind.

“Ay, ay, sir,” she replied briskly. “Ship's fully provisioned for the voyage, captain.” Despite her effort, the words came quavering a little. And now David perceived the distress she was striving to conceal. He swept her into his arms, and kissed her many times.

“Ye mustn't be unhappy, Ruth,” he commanded with a gentleness that was none the less authoritative. “I couldn't bear t’ think o’ ye mournin’ here while I'm out there in the world.”

The girl understood that he had no thought of giving up his purpose to save her from grief. The idea had not even occurred to him. She called it to his attention, but quite hopelessly.

“Can't you stay with me, Dave?” she asked, and in the inflection of the words was a prayer that he would.

Dave spoke sternly.

“I've done got t’ square my debt t’ yer pap. There ain't no other way.” His voice softened, and he held the girl closer as he went on speaking: “But I'll be a-pinin’ fer you-all, Ruth, all the time I'm away. An’ it'll seem a mighty long time, too.”

“You don't reckon it will really be very long, do you, Dave?” the girl asked, with a pathetic inflection of dismay at the suggestion.

“Shucks! No, o’ course not. ’Twon't take scarcely any time wuth mentionin’ t’ earn enough t’ pay fer them cussed limber twigs. An’ the minute I git a holt on the money, I'll come a-runnin’. An’ I won't be scramblin’ back so all-fired fast jest fer the sake o’ seein’ yer pap ag'in. It's you-all my eyes an’ my lips will be achin’ fer.” He kissed

her hair very gently, again and again. The perfume of it was like incense to him. The parting so near at hand pained him, but he felt that he must not give way to his own sorrow, since she must need his greater strength to comfort her in her womanly weakness. He patted her back in a clumsy effort to console.

Ruth stood clinging to him with her head buried in his bosom. She was crying softly, with little muffled sobs. This separation was to her a very terrible thing. It seemed to her that its coming thus immediately after their mutual confession of love made it all the more dreadful. There had been no time to realize the intercommunion of their hearts before a cruel fate interposed to thrust them apart. Even had matters stood merely on the former friendly footing between them, she must have found the abrupt departure of David a cause for suffering. Now, since the intimacy between them had developed into a mutual passion, she was stricken to the soul that the man she loved should go from her and leave her in desolate loneliness.

Ruth ceased weeping after a time, though she had heard but dully the murmured encouragement

and endearments with which David sought to cheer her flagging spirits. The change in her was due chiefly to a sudden thought that the expression of her despair would tend to make her lover too unhappy. So, with the instinct of self-sacrifice that is natural to the fond woman, she used all her strength of will to cast off the external signs of depression in order that she might not inspire melancholy in David when he most required courage for his adventuring out into the world. She raised her face and gave him kiss for kiss, and joyous words of love and trust. The young man responded gladly. He spoke with confidence of the future, of his hopes for a speedy return to her arms, of the perfect life they would live together through the long years to come.

It was midnight when the last farewell was spoken between them, and David pushed the skiff from the shore, and let it swing into the current of the river. The girl stood tense in restraint on the land, peering with dilated eyes to detect the final bit of shadow moving over the water, which gave the vague outline of the man she loved. And David, looking back as the boat drifted slowly down

the stream, held his gaze fast to that gray silhouette, dimly seen beneath the moonlight on the shore, which was Ruth—Ruth, his sweetheart! Then, presently, the ghostly figure vanished in the mist-wraiths, to be seen no more. A pang of infinite loneliness pierced David's breast as the vision of the girl faded from his view. For long moments he sat brooding, disconsolate and rebellious over the destiny that tore him from her. But, presently, the peace of the night touched him again with its benediction, and his sorrow fell from him. His fancy turned to the adventure that awaited him in the coming days. He bent to the oars and sent the skiff forward with long steady strokes. And as he sped on through the night, he was no longer lonely, for he was companied with his dreams.

CHAPTER V

FOR some hours David rowed steadily, though with a leisurely stroke. But on passing beyond that portion of the river most familiar to him, he gave over rowing, and with an oar for rudder, was content to let the skiff float lazily with the sluggish current. He chose this method of journeying not so much to escape fatigue as for the sake of caution. The waters of the winding stream were usually shallow, and although his craft was flat-bottomed with a draft of only a few inches, it was necessary to steer with care to avoid driving on one of the projecting rocks. So, the progress was slow, yet made with a luxurious ease that suited the traveler's mood and left him free for pleasant reverie. There was something almost hypnotic in that silent, stately floating over the velvet dark surface, between serried sentinel ranks of poplars and sycamores, which lined either shore. The moon dropped

toward the western horizon so that the boat moved within the heavy shadows of the trees, and David guided it almost by instinct rather than by sight. The moon dipped lower swiftly and set. The scene became weird; a vague and melancholy vista. A breeze sprang up before the dawn. The air grew colder, so that David felt the dank chill of it, and shivered. He shook off the sense of oppression that crept upon his spirits, and determined to make camp on shore.

He sent the boat rustling through the reeds that opposed their frail barrier between the channel and the bank. The skiff's bow lifted and slid up easily on a sandy beach. David clambered out. His movements were stiff at first from his hours of sitting during the cool night. But, very soon, his blood quickened its flow, his muscles became warm and supple again. His simple preparations were speedily made. The boat was uptilted on its side, propped in position by the oars, to serve as a wind-break. He did not trouble to cook a meal, but was satisfied with a few mouthfuls of cold meat. Then he rolled himself snugly in his blanket, and almost within the second was fast asleep.

The sun was hours high when finally David stirred, yawned noisily, stretched his muscles until the joints crackled in protest, and sat up. His mood was harmonious with the joyous day, and he felt a cheerful readiness to fare forward on his quest. He was beset with a ravenous hunger, and hurried the preparation of hot food from his store of corn meal, bacon and coffee. Then, replete, he resumed his journey.

For three days, David followed the course of the river at his ease. By night he would lie up in some sheltered nook on the bank, and by day he would drift with the current, rowing only occasionally in the more open and level stretches of water. The weather held fair, so that he suffered no discomfort from this source. The food supplies were ample for his needs, and he added to them with game that fell to his rifle. Flocks of wild duck and geese were frequent. Often as he rounded a bend of the river he would find them clustered thick before him. More than once his bullet caught a green-headed mallard before it could rise into the air.

It was on the third day, when he had traversed a distance of perhaps seventy-five

miles from the Swaim homestead, that David, at nightfall, drew near the city of Salisbury. Though unfamiliar with the river itself in this direction, he was able to recognize his surroundings by certain landmarks. Chief among these was the stockade of the Confederate prison, which loomed through the gloaming, sinister and hideous, on the higher ground above the river. The sight of it, thus vaguely seen at dusk, touched the adventurer's spirit with an unreasoning bitterness. He was not in the least repentant for what he had done here in a flush of generous enthusiasm. But just now he keenly regretted the miles that lay between him and the girl he loved. Here was the cause of their separation, and he loathed it accordingly. Then, inevitably, his thought jumped to the red-whiskered man, who had been first to rob the cripple, and thereby had precipitated the catastrophe. David felt a flare of fury against this fellow, as he had before while refurning from Salisbury. Now, however, his feeling was even fiercer, for this conscienceless rogue by his theft had come between the lovers. A surge almost of hatred swept up in the lad's bosom. His fingers

twitched convulsively, as if he longed to be at grips with the man, to thrash into him some sense of decency in his conduct toward cripples.

A faint, bell-like rhythm came down on the breeze. It seemed to issue from the direction of the stockade, and moment by moment it grew louder. David knew the sound, and his pulse quickened. He had meant to push on to the ferry landing a little way below, where the flat-bottomed scow was still poled across the stream, when any traveler blew a summons on the tin horn. He had intended to camp there for the night, and thence to walk the two miles into Salisbury next morning, to inquire for possible news of his father. But now he forgot the swift approach of night in this new interest in the sound borne to his ears by the wind. With a thrust of his steering oar he turned the skiff's bow to the shore. The bank here was high and steep, and the current ran swiftly. He caught hold of an out-jutting branch from a birch that grew on the shore, and so held the boat from being swept on. The rhythmic booming noise sounded more loudly. It was the baying of hounds.

The instinct of the chase set David quivering with excitement. What the quarry of the dogs might be he had no means of knowing, but he guessed that they must be on the trail of either a fox or a deer. He hoped that it might be the latter. His mouth watered at the possibility of venison broiled over the coals for supper. Still keeping the skiff in position by his grip on the bough, he seized the rifle with his right hand in readiness for instant action if the prey should come his way. Thus prepared, he stood poised, listening intently.

There could be no doubt that the chase was drawing nearer. There seemed every likelihood that the fleeing creature was striving to reach the river in a last desperate effort to escape its pursuers. The light was going fast now, but in the open space of the river it was still sufficient to afford a fair aim.

A crackling sound came from the underbrush that covered the shore. The noise of it increased. David wondered at the volume of it. Even a stag running its swiftest could hardly go crashing like that. It was heading straight for him, too—whatever the

thing might be. He still hoped it would prove to be a deer, although he doubted. The floundering body bursting through the thickets was almost upon him. He knew that in another second, unless pulled down by the dogs, it must break from the concealment of the woods. It was so close that there could be no danger of losing his opportunity by letting the boat drift, and he must have both hands for the shot. He loosened his clutch on the branch, the skiff dropped down the river. Even as it moved with the current, there was a final clatter of broken boughs at the edge of the high bank. A bulky something leaped from the shadows there, and hurtled forward in a long are toward the water. And in that same second when the boat began to move, David's rifle sprang to his shoulder, and his eyes lined the sights on the thing chased by the dogs. But the weapon did not belch its deadly missile. Instead, a gasping cry of horror broke from David's lips; his forefinger fell from the trigger as if palsied.

“Good God! an’ I almost got him!”

He shuddered, and felt a nausea.

“It's a man—an’ I almost got him! I

might have killed him! It was a powerful close squeak. An’ I thought I was jest a-gunnin’ fer supper!”

David sat staring in fascinated horror at the man who had thus escaped the trailing of the hounds, which now whimpered their distress from the shore. The fugitive had gone beneath the surface at his plunge. When he reappeared, spluttering, he started swimming at full speed toward the farther bank of the river, fifty yards away. But the shock of the cold water put too great a strain on his body, weakened and overheated as he was by his flight from the hounds. Suddenly, he uttered a shrill cry, threw up his hands, and sank.

The skiff, unchecked, had floated a considerable distance down stream. David was too far away to give immediate succor. But he lost no time before acting. In a moment he had dropped the rifle, and the oars were placed. He tested their strength in short, jumping strokes that sent the boat swiftly toward where the body must be swept along in the current.

It was the shallowness of the stream that gave David the chance of rescue. He caught

a glimpse over his shoulder of the drowning man's form being swept over a sand strip hardly submerged. He was able to bring the skiff alongside before reaching deeper water, which would have made his task difficult, if not impossible. He dropped his oars, and caught the half-unconscious man by the shirt collar. When he had secured a safe grip under the arms, he was able to get the fugitive aboard, thanks to the steadiness of his clumsy flat-bottomed skiff. This accomplished, he stretched the victim face downward, supported by a thwart under his belly, and proceeded first to empty him of the water and then to restore him to full consciousness by such vigorous methods as he knew. The treatment was, in fact, remarkably efficacious, so that within a few minutes, the man, after a final bit of strangling, aroused to consciousness with a piteous appeal for mercy from further ministrations.

David, greatly pleased with this result, lifted the fellow and turned him, so that he was in a sitting position. It was then, with his face close to that of the man he had pulled from the river, that David saw the features

clearly. At sight of them he started back with an exclamation of disgust.

“You!” he grunted savagely.

The irony of fate had made him the rescuer of the one man in the world against whom he cherished a grudge. He felt bitterly toward William Swaim, who had called him a thief. But he knew the justification for the old man's anger, and the fact that it was due to his own fault kept him from nourishing resentment. That fault on his part, however, had come as the direct effect of another man's mean action. The red-whiskered Union prisoner, who had stolen the first apple meant for the cripple, was the real cause of all the trouble. David had cursed that greedy prisoner often. Now he cursed once again, for it was the redwhiskered individual whom he had just saved from drowning and who now sat before him, gasping and shivering from his immersion in the chill stream. The young man made no secret of his feeling, but let his mood gush forth in stinging words.

“Ye thievin’, hard-hearted Yank’! As if ye hadn't given me trouble ’nough a'ready. Ye'r’ a plumb-ornery scallywag, a-stealin’

the apple I done throwed t’ a cripple. I ain't aimin’ t’ save sich as you-all from bein’ et by dogs er drownded. Hang yer carcass! Go ashore an’ let them dogs chaw ye up piecemeal as ye deserve. Er ye can drown. Git out, I'm tellin’ ye!”

The man, who had been dazed at the outset by David's violent denunciation, now in his turn recognized the young man who had thrown the apples over the stockade. Weakened by the peril through which he has just passed, he would have pleaded for mercy from the stalwart young man who stood over him so threateningly. But he had no time. As he shrank from the fierceness of the other's speech, David moved closer. When he ceased speaking, the mountaineer, in a final access of fury, picked up the wretched fugitive, and tossed him overboard toward the shore.

CHAPTER VIAS the unfortunate victim of adversity disappeared under water with a huge splash, David jumped to the oars, which he plied briskly to hold the skiff against the current. He had no fear lest the man drown, since he had tossed him into the shallows close to the shore under the bluff. But his indignation was not yet satisfied, and he meant to tell the fellow a few more candid truths concerning thieves and Yankees and oppressors of cripples. He only waited until the escaped prisoner should be in a position to give him due attention.

For the moment, the soldier was in too serious a plight to listen even to the worst abuse. He managed to get to his feet after hard struggling and stood tottering and choking from the water he had swallowed. The river rose to his armpits, and it was evident that he had need of all his strength to withstand the sweep of the current. When

he had cleared his lungs a little, he moved with clumsy, staggering caution toward the shore. He slipped, and only with difficulty saved himself from going down. Plainly, the man was almost at the end of his resources. David in the boat two rods away could hear the hiss of the hurried, painfully drawn breath, the panting sigh with which it was exhaled. The mountaineer was touched with compunction. The fires of his anger died. He felt ashamed of the harshness he had displayed toward one who, whatever his fault had been, was now deserving of pity at least for the suffering he had undergone already and those which he still faced. David was influenced, too, by the fact that the Union soldier made no plea to him for mercy, but maintained a stoical silence as he battled against the clutch of the stream.

The sympathy that stirred in David's bosom was quickened to action by a new factor in the situation. The dogs, at the place on the river bank from which the fugitive had leaped into the water, had been attracted by the sound of David's voice at the point below to which the boat drifted, or they had

caught the scent of their prey borne toward them on the wind. They came charging along the shore and only halted when they reached the high overhanging bank opposite their quarry. They rushed to the brink, but slunk back, unwilling to make the plunge down into the stream. They bayed and whimpered and growled with bared fangs. Even were the soldier to keep his precarious footing and escape out of the grip of the current, he would still have the bloodhounds to face, and they would be ruthless.

David had declared that he wished the fellow might be thrown to the dogs, but he had said this in a gust of wrath. Now that the reality threatened, he was horror-struck at the possibility of such a fate for any fellow human being. Moreover, there came to him in this tense moment a thought of his own father in the Northern prison, who might be in flight as this man and fighting to escape with his life from merciless foes. David felt the impulse to help the hapless Union soldier against his adversaries, even as he would wish some Northern lad in a position like his own to give aid to his father. And,

too, he was moved by an instinctive sympathy in favor of one against whom the odds were so heavy.

Now, another weight was dropped in the balance to make David's decision in behalf of the fleeing prisoner. A noise of shoutings sounded out of the woods some distance back from the river bank. There could be no doubt that these cries came from the guards who were in pursuit of the fugitive, and were now hastening in the direction indicated by the baying of the bloodhounds. If assistance were to be of avail, no time must be lost. The man himself was incapable of avoiding recapture. He had managed to approach more closely to the bank, and stood where the water was not above his waist line. But it was apparent that his strength was well-nigh exhausted. Even in the fading light he was visibly shivering from his contact with the stream. In his weakened condition, it would be manifestly impossible for him to breast the current and gain the farther shore of the river. On the bank before him, the dogs waited, frantic with desire to set upon him, to rend and throttle him. The beasts would be reinforced by the

pursuing men, whose shouts indicated that they were rapidly drawing nearer.

David hesitated no longer. With a strong push on the oars, he sent the skiff shoreward. He saw that the man feared his approach, naturally enough, for the fellow began a stumbling progress up stream away from the advancing boat. After the treatment he had meted, the mountaineer could not wonder that he was regarded as an enemy. He called out to advise the soldier of his change of heart.

“I cal'late mebbe I was a mite ha'sh. Leastways, I ain't a-goin’ t’ see ye et up by them durn bloodhounds.” The man had halted at David's placating address, and the skiff now drew close to him. “I ’low I'm plumb foolish, but I aim t’ git ye acrost the stream away from them dogs an’ the humans, too. Jest ye climb in here right-smart spry. There ain't no time fer shennanigin.”

The miserable object of the young man's compassion had no choice but to obey, though the expression on his face was of mingled alarm and perplexity over the kindly offer from the one who had just treated him with heartless violence. It is likely that he suspected

the lad in the skiff of being either drunk or crazy—a belief easy enough in view of the rapid and amazing inconsistencies in conduct. This astonishing and dangerous person had first rescued him and then thrown him out to drown, and now promised to rescue him yet once again. But, since he had no choice, he yielded to David's impatient command, and with much difficulty, due to his weakened state, managed to climb awkwardly over the side of the skiff, which the mountaineer held balanced against his weight. Then, the tension of his effort relaxed, he rolled on the boat's bottom in a huddled heap of misery, shuddering and groaning. The instant he was aboard, David bent to his oars, and sent the skiff at full speed out into the channel of the river.

The shadows of night had drawn down until even in mid-stream it would be difficult for those on the shore to pick out the shadowy movement of the boat. David made all haste, increasing his speed a little as the voices of the men indicated their arrival at the bank. Since no new outcry came from those assembled there, the mountaineer was sure that the presence of the boat had not

With a strong push on the oars, he sent the skiff shorewardbeen detected. But he continued rowing down stream with the current as swiftly as possible for a long way, until full darkness had settled over land and water. No sound or movement came from the collapsed form of the fugitive, except a feeble moaning and now and then a convulsive trembling. As David felt the chill of the autumn night, it occurred to him that the exhausted man in his drenched garments might suffer seriously from the exposure. He rowed in toward the shore opposite the prison, and peered sharply through the shadows for a landing place. He made out a tiny cove, and beached the skiff on the shelving sand. Then he busied himself alertly in caring for this enemy whom he had saved from the cruelty of the elements and beasts and men. The fellow, half-unconscious, yielded himself to David's hands without any attempt at resistance. The young man stripped off the sodden garments, and then rolled the soldier snugly in a blanket, and bestowed him in the bottom of the boat. This done, he launched the skiff again, and continued on down the river steadily throughout the long hours of darkness, until a ghostly gray

stealing into the horizon told that the dawn was near. Then, once more, he turned the boat's bow toward the western shore. After some search, he found an excellent landing in a little bay, where the entrance was almost concealed from any passing on the river by a luxuriant growth of reeds and alders. Pine woods ran down to the shore, offering protection from the wind, and affording abundant fuel. Here David made his camp. The escaped prisoner, who was now sleeping soundly, and whose moaning had ceased, was left undisturbed in the skiff where it was drawn up on the gravelly shore. Soon, a brisk fire was burning. David spread out the soldier's tattered garments close by the blaze to dry. Then he betook himself to the preparation of a meal, for which he himself, having worked through the afternoon and the night without any supper, was nearly as ravenous as he knew his starving companion must be.

The savory odor of sizzling bacon and eggs penetrated to the consciousness of the famished fugitive. Hardly had the bubbling begun in the skillet which David held over the coals when the soldier, although a moment before

sunk in profound slumber, suddenly sat up, sniffing rapturously. Drawn as the steel to the magnet, he got to his feet and climbed out of the boat and hurried toward the fire. He was not checked at all by the discovery that he was stark naked. He merely pulled the blanket about him Indian fashion, and went on.

David nodded in recognition of the man's need.

“Ready in a minute,” he vouchsafed.

When presently the fellow had been supplied with a tin plateful of the hot food, David was moved to new pity by the manifest hunger the man displayed. He let his own appetite go unsatisfied for a little in order to give his guest another helping. Then he cooked a second mess, which he divided between the two of them.

When the meal was ended, the mountaineer shifted into his best suit of clothes, and gave the other to the soldier, who, he now learned, was named Sam Morris. The clothes were ridiculously large for the Yankee, but they were whole and decent and he was pathetically grateful for the gift. His single possession of value that he had retained was

a battered old pipe, which had been long without tobacco. His happiness was complete when David gave him a filling for the pipe, and he sat for a time in silence, puffing luxuriously with that appreciation which is known only to those long deprived of such solace.

“I guess you saved me from bein’ drownded,” Morris said at last. “Your feelin's seem to be kind o’ mixed. I guess you meant well all the time except for a minute you lost your temper.”

“I ’low I was plumb het up,” David admitted reluctantly.

“An’ I ain't the one to blame you,” the soldier declared. “I don't wonder you had it in for me. It was a cussed mean trick, my swipin’ that apple from that poor onelegged boy of ours. But I tell you, mister, when a man's starvin’ he ain't rightly responsible for the things he does. A man's belly is a mighty sight bigger than his conscience. Why, mister, I just couldn't help swipin’ that apple. Was you ever hungry—real hungry, mister?”

David laughed at the patent absurdity of the question.

“Three er four times a day, ’s fur back as I can remember.” Then his face sobered. “But I cal'late I hain't ever been hungry like ye Yankees there inside the stockade. You-all was so pesky peaked and pinin’, it got me a-goin’ with them apples plumb reckless. If I hadn't been so wrought up, I wouldn't ’a’ been so darned free with another man's apples.” He chuckled amusedly over his own discomfiture.

“They wasn't your'n!” Morris cried.

David shook his head and his face lengthened. Then he told the full narrative of his exploit, while Morris listened eagerly, with many ejaculations of astonishment, of admiration, of sympathy.

“Gosh all hemlock!” he vociferated, when the tale was ended. “I certingly did get you into a peck of trouble, and now you're a-heapin’ coals of fire on my head, as it were.”

“I owe ye somethin’,” David replied with a grin, “fer that extry duckin’ I give ye in the river.”

The two men continued talking together for a time, discussing their future course of action. David, having embarked on the work

of rescue, was anxious to carry it to a successful conclusion. He felt a personal responsibility for the man whom he had saved from recapture, and the feeling offset his natural antagonism to this enemy from the North, so that he was willing to work in the fugitive's behalf. The fellow's frank confession of fault in stealing the apple meant for the cripple had done much to change the mountaineer's hostile mood to one of friendliness. It was quickly decided that the two should journey together to the coast. The soldier's identity would hardly be penetrated by the few persons they were likely to meet on the voyage, since in David's clothes there was nothing of his outward appearance to betray him. The chief need for caution would be in the matter of speech. He must speak little if at all, lest his Yankee drawl excite suspicion. With their plans thus settled, the men wrapped themselves in their blankets, and, both alike over-wearied, slept soundly until noon of the next day.

Their leisurely traveling down the river was for the most part uneventful. There were no signs of pursuit, and the few persons whom they encountered showed no suspicion,

for David did the talking, and they regarded his taciturn companion with the stubble of red beard as a fellow mountaineer. It was not until they came near to the South Carolina border that adventure befell.

Several miles before the Yadkin River crosses the state line, beyond which it flows peacefully on its way as the Great Pedee to mingle its cloudy waters with the clearer element of the sea, it passes through a narrow defile worn down through the stone of the cliffs by the ceaseless friction of the waters during untold ages. Here, within the canyon, the stream rushes madly in a sharp descent, crowded within lofty walls. The cavernous place echoes with the roaring turbulence of the stream. To-day the huge power of the rapids has been harnessed for the making of electric current to supply cities and towns far and near. But half a century ago, the waters raced in wasteful riot through a region that was a wilderness.

David, who was wholly unfamiliar with this portion of the river, was able nevertheless to calculate his near approach to the rapids by estimating the distance he had traveled from Salisbury.

He spoke of the rapids to Morris.

“I ’low we're plumb close t’ some rough water. I hain't never been this fur before, but, shucks! I ain't worryin’. I cal'late it ain't likely t’ be as bad as some rapids I've shot up in the mountains.” He regarded the soldier doubtfully. “Be ye a-feared? If so be, I'll set ye ashore when we hear the river begin thunderin’. Ye'll have a mighty hard climb t’ the foot o’ the rapids, I reckon, but it'll be safer, like's not, even if ye break a leg on the rocks. But I'm thinkin’ ye wasn't born t’ be drownded.” He chuckled reminiscently.

Morris, too, grinned in response.

“I guess I'll stick to the boat,” he asserted. “I've been down rapids myself,” he added boastfully. “Up home, our Sunday school had an excursion to Ausable Chasm. Fine rapids there, by cricky! Went down in a steamer. It bobbed around something scandalous. The women was all a-squawkin’ an’ hangin’ onto the men. I was close up to a pippin of a girl, but she didn't seem to have her right senses like, and hugged an old mossback with a fat wife, what clean forgot about them rapids in telling

the girl she was a hussy and how to behave.”