| SPECIAL COLLECTIONS ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #18 | |

| Dr. Durwood T. Stokes | |

| Chairman of the Department of Social science and professor of history at Elon College | |

| March 27, 1974 |

Herbert Paschal:

I believe it’s 9:35 or past, and in keeping with our announced schedule it is now my pleasure officially to convene the second annual Tobacco History Symposium at East Carolina University. This symposium has as its central theme this year, “Tobacco’s Impact Upon Towns and Town Life in North Carolina.” It has been arranged and organized by the director and assistant directors of the Institute for Historical Research in Tobacco, which is sponsored by the Department of History of East Carolina University. With the help of the Division of Continuing Education of East Carolina and the financial assistance of the North Carolina Committee for

Continuing Education in the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Humanities, it is here gratefully acknowledged without their assistance this day would certainly have not have been possible.

Through the years I have had the pleasure of teaching I guess literally thousands of East Carolina students, some hopefully some North Carolina history, and in the classroom I’ve attempted to stress certain prime forces and elements in North Carolina history, things that have moved and shaped the history of this state, such things as bright leaf tobacco, the dangerous coast of North Carolina, the problem of sectionalism in North Carolina. We have on our platform this morning one of those forces and elements which have continued to shape North Carolina in the twentieth century, and we are very proud indeed to have to extend the welcome to you this morning the chancellor of our university, Dr. Leo W. Jenkins. Dr. Jenkins.

Leo Jenkins:

Dr. Paschal. It’s a pleasure to welcome all of you here. There is an old saying that people who do not look to their past don’t have much of a future, and I think it’s very proper that we do come together and talk about things that made North Carolina and put us where we are right now. Normally in these days whenever you go to a meeting and you’re associated with a college or university they want you to talk about streaking, so I hope you don’t have any streaking going on here today. [Laughter] Of course even that’s a good movement, Herb. I think historians will say that it did bring the town and the college together. [Laughter] We have more visitors now than we ever did sometimes. We had a convoy come over from Kinston the other night when the radio man said there’s going to be some streaking, so the whole convoy of them came. It was nice. I know they came over to see our buildings and [Laughter] [what

we’redoing here.] You know the grasshoppers and the roaches had a symposium similar to this, Dr. Paschal, at one time. After the keynote speaker made his talk he entertained questions, and a little grasshopper jumped up and said, “We have a real problem. Every winter we die.” And the expert said, “Well that’s easy to solve. When it gets a little chilly and you think winter’s coming on change yourself into roaches. Then you can eat the best of food and live in warm homes and enjoy the winter,” and everybody applauded. This little grasshopper got up again and he said, “I’ve got a second question that pertains to the first one,” and the speaker was a little bit tired of him and he said, “What is it this time?” He said, “Well how do we turn ourselves into roaches?” He said, “Well let me make one thing very, very clear. I’ve come here to give you the big idea; you work out the details.” [Laughter] So anything that you might hear, you work out the details of it.

We have a big operation going here, as you know, and we’re very honored really when people from the business community, particularly those of you who represent our biggest piece of the economy in Eastern North Carolina, the tobacco industry, come here and spend some time with us. It costs us about twenty-five million dollars of your money and the money of parents of students, which is still your money, to run this institution. It’s a very expensive undertaking. We have some fifteen hundred full time employees. As a matter of fact we have more employees here now than we had students when I came here, and they come from all over the world and they are trained in some of the greatest of our universities, so it’s only right and proper that the expertise that does exist on our various campuses should be brought to the attention of our citizenry. So we are very honored and pleased that you have elected to come and

spend a few hours with us. I wish I could spend some more time with you. I’ve got a gang waiting for me at 10:00 this morning and then I’ve got to run on to Chicago, so our life gets to be such that we don’t get the chance to enjoy it as much as I would like to. But again you’re very welcome and I know you’ll have a very fine symposium. Thank you very much.

Herbert Paschal:

Thank you, Dr. Jenkins, and good luck on your trip. It’s my pleasure now to introduce to you the director of the institute, who has worked long and diligently to bring this program together today and to make possible this second symposium. Without further ado, since most of you have not had the opportunity to meet him, I introduce the director of the Institute for Historical Research in Tobacco, Dr. John Ellen.

John Ellen:

Thank you, Herb. It’s good to see a number of you folks back again this time. This is our second venture, our second annual symposium dealing with the history of tobacco. Let me add a real warm welcome to that of the two previous speakers, this one on behalf of the Institute for Historical Research in Tobacco. It was just one year ago that we welcomed a good many of you here. It’s good to see you back again, as I just emphasized. Last year’s program featured a number of top names from the elite among tobacco historians, and as you’re all well aware there are not too many of this type person around. Thus we’re very proud personally to be able to return several of these speakers from last year to this present symposium. Some of the more popular ones will be with us again today: Dr. Nannie Mae Tilley, Melvin Herndon, and Robert Durden, all big names in the area of tobacco history and telling the story of tobacco. These plus Durwood Stokes of Elon College and Bill Humphries, the farm

observer, will constitute our program main speakers for the day. I think it’s a real strong program, we’re proud of it, and I believe they will cover the theme we have for this year, “The Impact of Tobacco upon Towns and Town Life in North Carolina,” and they will cover it very well.

For the benefit of those who are attending their initial tobacco history symposium, let me quickly refer to the essentials which have made this program a reality. Tobacco has been a major force in the lives of the people of this state since the first Virginia settlers came in the mid-seventeenth century, around the Dismal Swamp and into Albemarle Sound. The Virginians brought with them their love for this crop, which quickly became the colony’s first important staple. While tobacco declined sharply in importance in the antebellum North Carolina era, production began to expand rapidly in the late nineteenth century. The twentieth century has seen North Carolina become not only the world’s leading producer of tobacco leaf but also the world’s leading manufacturer of tobacco products. Tobacco has really played a dual role, a twofold role, in the development of this state in the area of urbanization, and that’s an area that we are dealing with primarily today. It has acted both as a deterrent on occasion and as a stimulus, as a stimulus particularly to the rise of certain marketing and manufacturing centers. More important, however, has been the impact of this crop on the day-to-day lives of rural and urban North Carolinians and indeed upon their counterparts in other Southern tobacco producing states. Thus there was and is a definite need for developing a major center for the study of the extent of this tobacco’s impact upon those whose lives have been touched by tobacco and the tobacco industry in order that you and we may understand and appreciate that society which has

developed around this major staple crop. In this way the strengths and weaknesses of this society resting upon a tobacco-based economy can be more readily ascertained and those values most worthy of retention can be identified.

To launch such a study of tobacco history and its impact upon this state in particular, the South, and the nation, the Department of History of this institution has founded the Institute for Historical Research in Tobacco late in the year 1972. This organization is now beginning to accumulate resources necessary for the long and involved task of studying the tobacco society’s evolution. The first major effort of the institute, the better understanding and interpretation of the tobacco story, was last year’s symposium. Academic humanists with varying competencies in the history of tobacco and a cross section of persons comprising the tobacco society, growers, processors, manufacturers, exporters, buyers, other industry personnel and interested persons attended that meeting. The papers were presented by able speakers. Discussion and questions sessions followed. As a result, some of the doors to understanding the tobacco story and tobacco society were opened a bit wider and a number of suggested paths for fruitful research in the future were pointed out to various ones of us.

Secondly, and integral to the ongoing program of the institute, is a need to acquire by gift and/or purchase basic works on the history and development of tobacco not already held by the East Carolina University Joyner Memorial Library. Acquisitions in this area have been encouraging this year, certainly, and more about that later on.

Thirdly, essential to the long-range project is the developing of a center for collecting manuscript materials, records of all aspects of the tobacco society, including farm journals, marketing warehouse records, personal correspondence relating to tobacco, records of manufacturing companies, exporters, and so forth. Acquisitions are being housed in the East Carolina Manuscript Collection in the Joyner Memorial Library. Desirable manuscript offerings have first to be located, of course, evaluated, and if deemed important acquired by gift or purchase. This manuscript repository will provide a center for the study of the tobacco society and a means of interpreting that society’s past and its present. Unusually important and revealing documents casting light upon the tobacco society can be reproduced and given wide distribution at a minimum cost. Of course these documents, too, must be first collected and identified, before they are ready for reproduction. Professor Don Lennon, the director of the East Carolina Manuscript Collection, has been soliciting tobacco materials for some time now throughout this entire tobacco region. Success in this area was very slow at first but has become most rewarding in the last few days. More about that later.

Once again we solicit your interest and support, not only in ferreting out available manuscript materials, but also your support in acquiring those of real value to the program already described. We believe that Greenville and Pitt County, located in the heart of the large eastern bright tobacco belt, is a logical center for collecting and housing primary and secondary resources relating to tobacco in the Carolinas, Virginia, and other southern tobacco producing states.

And now just a few housekeeping chores for the day. We have a light problem, as has already been affirmed. They’re working on the lights apparently and hopefully

they will be in better shape. All we have is a few spots at the moment. It’s like the energy crisis has really gotten us. It was not planned that way I assure you, however. If you have not registered and picked up a name tag please do so in the lobby at your convenience, by the noon hour. The program as printed on the brochure is intact as far as I can tell at the moment and thus we did not print any additional throwaway programs this year, as we did last year. Coffee will be available in the lobby during most of the day. As far as points of information about this particular building, the Allied Health Building, restrooms are located just behind the platform and outside the auditorium, as you are facing now, men on the right, ladies on the left. There is a pay telephone in the west wing of the lobby for those that might need to make a phone call. There was a no smoking sign here, but there are ashtrays around, and I don’t see it at the moment so we won’t worry about that, I suppose. Those signs are in all state university auditoriums automatically, as I understand it. We used ashtrays last year with reckless abandon, so those who want to light up, please do so.

I feel certain that all of you will want to hear Bill Humphries at the luncheon today. He’s a former farm editor of the Raleigh News & Observer, for some twenty years I suppose, and now associated with North Carolina State University in another capacity but still in agriculture, of course. The luncheon is scheduled for 12:30 at the Ramada Inn, the restaurant, which is about a quarter of a mile or less west of this building on US 264 Bypass. There should be adequate parking there, as there doesn’t seem to be here. We may use the east side entrance of that building to a room in the rear of the restaurant. Tickets are on sale in the lobby. They’re three dollars per customer and may be purchased until 12:30. The afternoon session featuring Nannie

Mae Tilley and Robert Durden is slated for 2:30 in this auditorium, so we will have roughly about a two-hour period to get from here down to the Ramada Inn and back, those of us that are going to the luncheon, and return. Once again, welcome. At this time I want to turn the direction of the morning session over to a friend of mine and history colleague, Professor Fred Ragan of the Department of History, one of the associate directors of the Institute for Historical Research in Tobacco and one of its most ardent supporters. Thank you. Fred.

Fred Ragan:

Thank you, Professor Ellen. I, too, extend a welcome to the Tobacco Institute, and the first part of our program deals with, of course, tobacco in the towns. Our first speaker is Professor Durwood T. Stokes. He’s a native of North Carolina; received his graduate degree at the University of North Carolina; presently is an officer in the North Carolina Historical Society. He’s the secretary-treasurer of that society. Recently he has been commissioned to write a history of Dillon County, South Carolina. He’s published a number of articles in the North Carolina Historical Review and the South Carolina Historical Magazine. One of those articles deals with the town of Milton, the town that he will be speaking about today. It deals with the Milton Chronicle, the newspaper of the town. Professor Stokes is chairman of the Department of Social Science and he is a professor of history at Elon College. His topic this morning is “Milton: The Growth and Decline of a Tobacco Town.” Professor.

Durwood T. Stokes:

Durwood T. Stokes: The town of Milton in northeast Caswell County, North Carolina, is situated on a high ridge which slopes steeply downward on the south side

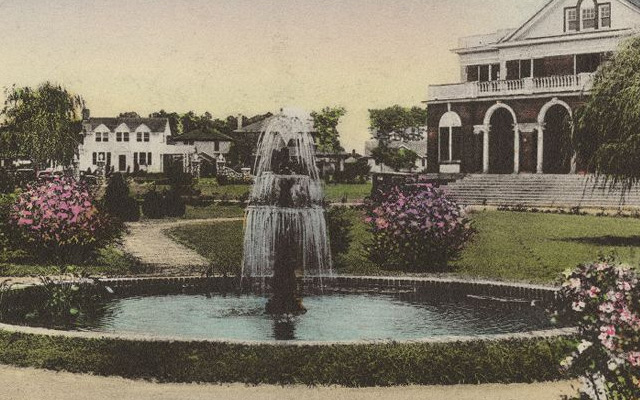

to Country Line Creek and on the north side to the Dan River and the Virginia state line. It was named either for Robert Milton, a pioneer settler in the vicinity, or for Thomas Milton, who operated a mill in the area. As early as 1728 a settlement had been made on the site and the name which became permanent was in common usage by May 11, 1781, when the Marquis de Lafayette wrote a letter headed “Milton” to General Sumner. A census taken in 1784 showed Caswell County to be the second most populous county in North Carolina, and doubtless some of this growth was centered in Milton, for the town was incorporated on December 23, 1796, eight days earlier than Baltimore, Maryland, received its corporate charter. Almost immediately Milton became commercially important and throughout the nineteenth century its fortunes rose and fell on succeeding waves of prosperity, after which it experienced a decline and its prestige catapulted downward to its present unimpressive level. Although it remains today the only incorporated town in Caswell County, Milton’s population has shrunk to a fraction of its peak figure and only a vestige of its former importance remains. The extent of the resulting obscurity was clearly evident in 1971 during the town’s 175th anniversary celebration. On that occasion Governor Robert W. Scott, one of the most widely traveled chief executives this state ever had, confessed in his address that while he was born and reared only some 50 miles distant, he never previously visited Milton. The prime factor in this ebb and flow of commercial prestige has been tobacco.

There is not an abundance of factual material on the history of the Caswell community, especially for specific periods of the town’s existence, but the fragmentary data which has been preserved, consisting primarily of newspaper articles and

contemporary accounts, furnish a deep and intimate insight into the events that transpired and supplement the more impersonal statistics and general records. For this reason the extant information presents a more complete picture than its meager quantity would ordinarily indicate, and it is this material which delineates the role of tobacco in the story of the town. Significantly, Milton’s charter specified that as soon as the town shall be laid out inspectors of tobacco and flour be appointed by the town government and warehouses erected for the storage of these commodities.

This provision is understandable, for throughout colonial North Carolina, hardly a more suitable area for agricultural development could have been found than the valley of the Dan. In 1728 William Byrd described the bent of the river as “a level of exceeding rich land full of large trees and covered with black mould, as fruitful as that which is yearly overflowed by the Nile.” This promising area was settled by farmers and tobacco, being a profitable agricultural crop, was cultivated as early as any in the area. Milton soon became the focal point in the region where farmers could sell their cured weed and the commercial buyers could then ship their bulk purchases by barge on the Dan River into Virginia. There was no appreciable competition from other Caswell communities, because they lacked the facility enjoyed by Milton of being on the banks of a navigable river, which flowed into the adjoining state. In 1810 Bartlett Yancey observed that Caswell’s staple commodities of tobacco, cotton, and [26:09] flour: “We generally send our produce to Petersburg and Richmond.”

Milton was the gateway to the Virginia markets, and by this time sufficiently profited by this advantage to boast of two stores, a saddler’s shop, a hatter’s shop, a tavern, with about fifteen or twenty houses, according to Yancey. At this time Milton

was sharing with most of the United States a prosperity caused by the boom which followed the War of 1812 and in most accounts of the town’s commercial growth tobacco is prominently mentioned. In 1818 the Raleigh Register commented:

This newly established little town on Dan River flourishes beyond any example in this state. Property which a year ago would not have sold for fifteen hundred dollars will now command fifteen thousand. Lots on the main street sell at the high price of a hundred dollars a foot front. Land in the neighborhood is also in proportion.

Archibald DeBow Murphey, who had been one of the commissioners appointed to lay out the town for incorporation, was so impressed while doing so with the potentiality for its growth that he invested in real estate in the vicinity. Writing to Judge Ruffin in 1818, he included a glowing account of the town:

As to Milton, speculation has raised there beyond my expectation. Lots on the main street have sold for nearly an hundred dollars per foot. The company--that’s probably the Roanoke Navigation Company--have laid out a new street and sold a few lots. Their sales have already exceeded fifty thousand dollars and they expect the residue of their lands will bring seventy-five or a hundred thousand dollars. About fourteen hundred hogsheads of tobacco have been received there. Lands in the neighborhood are selling from twenty to fifty dollars per acre. I understand that more than five hundred hogsheads of tobacco have been received at Danville and that the property which I sold Mr. [28:18] would now sell for more than a hundred thousand dollars. A great deal of capital is centering in Milton and Danville.

The possibility of connecting the waters of the Roanoke and Dan Rivers by canal was a subject of general interest at the time, and this contemplated project inspired a comment in Niles’ Register:

The improvement in the navigation of the noble River Roanoke we have hereto observed has given birth to several new and thrifty villages. We have just received the fourth number of a well printed newspaper established at the new town of Milton, North Carolina, which also has a post office, and at which fifteen hundred hogsheads of tobacco were received of the last crop. The New Bern Bank has an agency to place and another is expected from the state bank.

However, this rosy economic bubble was pricked by the Panic of 1819 and its effect, mentioned in a letter written by Alexander Murphy, a Caswell planter and merchant, to Col. Murphy: “Business is quite dull. No sales of property can now be made,” he wrote. This commercial deflation was discouraging but the staunch Miltonians were doggedly determined to forge ahead regardless of falling real estate prices as there was still a demand for tobacco. John H. Perkins began publication of the Milton Intelligencer in 1818, which was not only the first in Caswell but the only newspaper at the time between Greensboro and Hillsborough. Although the paper changed owners and names several times, the newspaper was published in Milton almost continuously throughout the following century. At the same time, the tobacco market was enlarged and the Roanoke Navigation Company, also known sometimes as the Roanoke and Dan River Navigation Company, expedited the freight shipments on the river. Encouraged by improving transportation facilities and aware that there was a profit both in growing tobacco and in processing it, several Caswell entrepreneurs founded establishments in manufacturing plug chewing tobacco for the general market. Because of the success of these factories, new and larger stores were opened in the town. Mills were established for the processing of oil and the manufacture of woolen goods and cotton cloth. Doctors, lawyers, and insurance agents opened offices and even a dancing master sought pupils for his classes. The mulatto Tom Day advertised his cabinet shop where the furniture he made, so highly prized today by collectors, was for sale. A hotel was built and two boarding schools opened, one for boys and one for girls. Religion was not neglected and a Presbyterian church founded in 1826 enrolled thirty members in less than two years.

These and other developments were encouraging, but while they were taking place Miltonians kept a wary and somewhat jealous eye on Danville, a few miles away on the Virginia side of the river. Incorporated in 1792, that town was reaping the same benefits on the north side of the fertile Dan valley that Milton was harvesting on the south side. Competition eventually rose from other towns, but it was Danville that became the chief rival of Milton for the domination of the area’s commerce, of which tobacco was a substantial part.

While Milton was growing appreciably during the antebellum period, farming in Caswell changed for the most part into a plantation regime, as Miss Nannie Mae Tilley has stated in her study of the tobacco industry. The county was more suitable for the growing of tobacco than cotton and crops were profitably produced by slave labor. As a result, the valued black manpower supply outgrew the white population in numbers according to the census reports, which in 1800 had 5,887 whites, 2,788 slaves, and in 1860 there were 6,587 whites and 9,355 slaves.

The profits from this labor supply enabled the plantation owners to build impressive homes, entertain lavishly, enjoy fishing and hunting on an elaborate scale, and maintain stables of blooded horses for racing. The latter was so popular that the sport of kings became the king of sports in Caswell County, with Milton at its center. As early as 1810 Bartlett Yancey mentioned the organization of the Jockey Club [of the] Caswell [33:21] and boasted: “Few counties have more useful elegant horses. They are from the stock of [33:27], True Blue, [33:29], Magic, and [33:31]. There are valuable horses from [33:33] and nonpareil.” Later [33:37], Harry Clay, and Passover were added to the list. Even impressive stud fees of twenty-five dollars could hardly

have completely financed such an expensive sport, and what other major source of revenue did the sporting planters have than their tobacco profits? Unfortunately, they did not seem to realize that the enjoyment of this pursuit might not be always possible.

However, tobacco caused no worry at the time, for the local newspaper quotations show that the price paid for the golden weed steadily increased on the Milton market during the two decades preceding 1860. Out of a table I have here I’m going to read the quotation for Choice Tobacco, which in 1841 was selling from ten to twelve dollars and in 1857 advanced to fifteen to eighteen, and the other was similar in rise. These prices compared favorably from those also quoted from the markets at Petersburg, Lynchburg, and Richmond, but significantly the Milton paper omitted quotations from the Danville market, even though they were probably in line with other prices elsewhere.

In 1841 Charles Napoleon Bonaparte Evans bought the Milton newspaper, renamed it the Milton Chronicle, and published it almost without interruption for nearly half a century. This highly intelligent and gifted editor immediately became the most vociferous booster for the town, the leading champion of the tobacco industry, and the most severe critic of Caswell County agriculture. In 1850 Evans jubilantly announced:

Thirteen hogsheads tobacco made by Mr. N. Norwood, Warren County, North Carolina, said to be the most inferior crop grown by him for several years, was sold in this market yesterday by Mr. John M. Shepherd, Jr., commission merchant, at the following satisfactory prices: four hogsheads at twelve dollars, one at ten dollars, four at eight dollars, three at seven dollars, and one of lugs at six dollars.

In the same issue of the paper the editor replied cockily to an article in the Danville Register which boasted about the ten tobacco factories in that town:

We believe our four factories can’t be beat by either the ten in manufacturing good chewing tobacco, and we dare the ten to send us a

plug of their best to compare with a plug of the best from the four factories in Milton. The factory that don’t send us a plug will be durned afraid to come to trial and treated accordingly.

So much for that.

Eight years later the following appeared in the Chronicle:

Think of sixty dollars per hundred for tobacco in Milton and tell big Richmond and Lynchburg to spur up their steeds. We have no humbuggery in our market. Our manufacturers are plain, solid, matter of fact men who do not seek to deceive planters by false appearances.

These articles indicate tobacco had become big business in Milton. Joseph Clark Robert in his study of the industry summarized the importance of the commodity as follows:

By 1860 the manufacture of tobacco ranked among other industries in North Carolina fifth as to capital investment, fourth in value of product, and third in cost of raw material and number of hands employed. Of the ninety-four factories operating in the state at that time the eleven in Caswell were considerably larger than the others and five of these were in Milton.

These plants were of primary economic importance to the town, although the exact extent of the operations is difficult to determine. When the establishment of George W. Thompson burned in 1861, it was described as an extensive tobacco factory and the loss included at least 20,000 pounds of loose tobacco and 40 boxes of the manufactured product. In the same newspaper which reported the event, an account was given of a fire in Person County which destroyed the factory of Green Williams valued at $20,000. Since the Caswell plants were the largest in the state, each of Milton’s plants must have exceeded $20,000 in value and therefore represented an impressive capital outlay for the period.

In 1850 the value of the freight shipped annually from Milton was approximated at between twenty-five and thirty thousand dollars. At the same time, Danville claimed seventy thousand dollars worth annually, including her cotton goods, which evoked a derisive comment in the Chronicle that, “We had supposed the freight to and from both towns combined fell short of this sum,” and that the nearest cotton factory to the Virginia city was in Milton. Tobacco undoubtedly accounted for most of the poundage shipped from the Carolina town but not all, for Milton had other industry including a cotton yarn mill described as unsurpassed in the South for its splendor and magnificent operations. So, even with tobacco reigning as king, there was some diversification in Milton’s industry and even a small amount in Caswell’s agriculture. The newspaper often strongly advised both town and county that there should be much more. In 1855 the critical Evans published the following sarcastic caution to farmers:

Bacon and lard: These articles are in great demand in Milton. Not a pound of the one or the other can be had for love, money, liquor--how surprising--or affection. Meat, meat, more meat, and less tobacco.

In the same issue of the Chronicle, the Caswell County agricultural fair was discussed:

We hope the farmers and mechanics, the maids and the matrons duly appreciate its importance. If farmers would think more of agricultural pursuits and less about political parties the county would be vastly benefited. If the agricultural society of Caswell would advise more attention to the raising of corn and hogs and less culture of tobacco it might do good. We have lately seen large tobacco growers running from pillar to post trying to buy something to eat and couldn’t do it. Such men ought to fast for a few days.

Two years later, in a more somber vein, the warning was repeated:

The time for planting is close at hand and it is to be hoped that farmers will think of something besides tobacco. Folks may eat tobacco but they can’t live on it, nor can they live by looking at the money they

got for it. Better raise your own stock and plenty of food for man and beast, like our kind and venerable friend John Gunn, Sr., who is undoubtedly a model farmer if not the best in Caswell. Horses are now going at tall prices. Raise them for yourselves. Blue beef sells high, and we can’t get a milk cow worth having short of a big price. Raise more cattle. And there is naturally a four-legged hog for every two-legged one that preys upon hog meat. Raise your own hogs and plenty of them. Don’t let baccer starve us all out.

The sage editor of the Chronicle was neither a sensationalist nor a false alarmist. Why then, with tobacco selling higher than ever, the factories running full time, and the county prosperous, did he have qualms about the future of tobacco? One of the reasons began with the discovery by the Slade brothers about 1852 of the new method of curing the weed to produce the bright yellow tobacco leaf which instantly became popular and caused the price of the commodity to skyrocket. This even occurred in Caswell County, and as a result the farmers of that section increased their acreage, concentrating on the big money crop even if the growing of needed food and forage had to be neglected. This was one reason Evans was apprehensive, for such a program seemed foolish to him and he said as much. Another reason for the publisher’s concern was that the railroads had come into the picture and the Dan River freighters faced formidable competition from the new carriers. Evans was convinced that the iron horse would eventually win the race and later events proved him to be correct. So for these two reasons, if no more, he fought harder than ever through the power of the press to help his team win.

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century the batting averages of the two rival towns had been on the whole about equal, but when the Richmond and Danville Railroad was chartered in 1845, Danville’s score began to climb. Strenuous efforts were made to have the [track] routed through Milton, but when that battle was

lost a statement in the Chronicle expressed the hope that the tracks would be laid far away from the town. This comment has been misconstrued to mean that the Miltonians did not want a railroad at all. Actually, the town desired one very much, but not one that would bypass the town while draining the freight from its nearby trading area in the other towns, especially Danville.

The Milton population were then exhilarated over the defeat of the so-called “Danville [Steal]”, in which plans were thwarted to construct a road from Charlotte, North Carolina, to Danville, but the joy was short lived as the North Carolina Railroad was chartered in 1849 and bypassed Caswell County entirely. The undaunted editor next led a movement to solve the new dilemma and in 1850 suggested the following plan:

We now contemplate a branch railroad with the central route in this state, to tap it somewhere in Orange or Alamance. To do this we shall only have some twenty-four or twenty-eight miles of road to build. If we can get this branch we promise the state and Wilmington in particular to pour the rich products of the valley of the Dan in to the Wilmington market.

This proposal failed to secure sufficient financial backing and by the mid 1850s cars were running on a completed road and carrying freight into Danville. Still Milton did not give up, and ferried goods across the Dan to a junction on the Richmond-Danville line. By 1858 the large number of ferry boat accidents inspired a clamor for a toll bridge built across the river so that Milton’s freight could be hauled by wagon to the Barksdale depot.

During the years when the railroads were under construction, the North Carolina legislature issued numerous charters authorizing the building of plank roads. Milton obtained one, but the timbers were never laid. Instead, the Yanceyville and Danville

Plank Road was completed and Milton cut off from the flow of traffic more than ever. However, the possibility of building a railroad from the town remained, and in 1860 Editor Evans used all the rhetoric for which he could find printer’s ink to promote the project:

What stronger appeal could be made to the interests of patriotism of our people than the fact that this significant enterprise is put in jeopardy for the want of a comparatively trivial amount--sixty thousand dollars. Will they allow it to fail? Then they close their eyes to its vital importance and suffer it to fail by their default.

Public pulse might have been sufficiently stimulated by this appeal to finance the road, but the unfortunate war for Southern independence began the next year and most construction came to an end for the duration. The Milton Blues, which included most of the youth of the town and county, dutifully mobilized and bravely marched away to join the Confederate forces in Virginia. With the railroads busily hauling military supplies, Milton was able to again use the Dan profitably for her freight and tobacco continued to absorb the interest of Caswell to the neglect of other crops. In 1863 one frustrated citizen inquired of the Chronicle, “What has a body got to do that can’t buy bacon, beef, nor fowl, even if he has the money to pay for it?” to which the irritated editor replied, “Join the army.” [Laughter]

In the same year [Break in recording from 46:55 to 47:43; end of side one of tape] who was then fighting in the Army of Northern Virginia, finally released his pent up ire on the subject of tobacco:

It would be a glorious deed for the Southern Confederacy if every tobacco factory in it were burnt to the ground and their very ashes scattered to the four winds of heaven. These moneymaking machines are mainly responsible for the exorbitant prices now charged for the accessories of life. Plenty of money and no poor kin, they stand on price. They would as soon give fifty dollars a barrel for corn as five or five

dollars a bushel for potatoes as twenty-five cents. We hope our legislature will pass a law not only suspending the manufacture of tobacco but imposing a fine of ten dollars on every tobacco plant cultivated during the war. Our idea is that people can do better without tobacco than meat or bread.

Again the crusading editor had made a plea for agricultural diversification and as later events proved again it was for the most part unheeded.

When the war ended, Milton’s prosperity suffered extensively from the fall of the Confederacy. Part of her industry failed to survive the conflict; more succumbed to the economic rigors of Reconstruction. However, there was still a market for tobacco and it remained king although the throne was considerably shaken. After an abortive attempt to increase planters’ interest in the profits from drying fruits and growing broom corn, the Chronicle’s editor disgustedly ceased advising farmers and concentrated on the town and its market. “Let’s get up a steamer on the Dan and enlarge the tobacco market,” he wrote in 1869. Evans then turned his attention to the problems of the factories and made this radical proposal:

We know of one and but one way to get the tax taken off tobacco, and that is for the manufacturers in the South to hold a convention and all hands resolve to stop manufacturing and stop at once. This would give all the manufacturing business entirely to the North where the best government the world ever saw, in the kindness of its honest and fair dealing heart, has been working these many years to transfer it, and presto change, the whole tax would be at once taken off tobacco. The thousands of Negroes who would be turned out to starve could amuse themselves by making tobacco for the Northern factories, but we would advise anyone else to make it. If they go north the whites will not let them work in the factories and then they can’t vote nor hold office. Let us quit manufacturing and stop all the distilleries for two years, just to see what effect it will have on the national treasury and infernal--that’s a quote--revenue collectors. [Laughter] The best government the world ever saw ought not to rob us of our little hard earnings after robbing us of our Negro property. “It’s a shame,” an honest old Negro told us a few days ago. He thought it was a damn shame. He was abusing the government for turning him out to starve in the name of freedom.

This scathing article was doubtless easy for the editor to write because, as Robert pointed out in his study, the relationship between the tobacco manufacturer in the South and the factory in the North was not entirely satisfactory, even in the best of times, and during the trials of Reconstruction it was only natural to lay the blame for both old and new grievances on the federal government, and Evans caustically did so.

Transportation facilities during the post-war period continued to be the major problem of the town on the Dan. During the war years the North Carolina legislature chartered the Piedmont Railway Company to connect the Richmond and Danville line with the North Carolina Railroad on the best, cheapest, and most direct practicable route. Again Milton was bypassed, and on February 14, 1866, the first cars ran on the new road from Greensboro to Danville. The Roanoke and Dan River Navigation Company was still Milton’s only transportation facility and while it was proclaimed alive and kicking in 1869, the Chronicle interpreted this to mean, “that is it kicks after collecting tolls but is as dead as the [52:16] as far as working on the river is concerned.” This criticism was deserved, for the company became increasingly indifferent to serving its customers and when it expired in 1880 the comment was that it should be made to return the tolls it collected for the last twenty years.

In addition to these transportation problems, the Milton tobacco market was suffering from other ailments. According to Miss Tilley’s study, the warehouse auction method of selling tobacco originated before the war in the Danville area. It’s claimed by some that it even originated in Milton, and it was in vogue generally by 1870. A state tax of fifty dollars plus a county tax of fifty dollars and a town tax of five dollars levied on each warehouse was regarded as adding insult to injury, and in 1877 the

Chronicle predicted such an unjust revenue persecution would soon drive the tobacco into the Virginia market to be sold and manufactured. This prophecy was alarming, for if tobacco were ever forced to leave Milton what else would be left? The plight of the town on the Dan at this time was sad indeed, with slave labor in the county gone forever and luxurious living, including expensive horse racing, had gone with it. One by one, Milton’s industries were forced by the transportation bottleneck to either close their plants or move their operations elsewhere, and the mercantile business suffered correspondingly. Only tobacco was left and it was in trouble. Little wonder that Editor Evans swallowed his pride and solicited advertising from Danville’s merchants for the Chronicle on the grounds that it circulated in Caswell and adjacent counties that traded largely in Danville.

By this time the Miltonians finally realized that they must make a desperate effort if their tobacco industry was to be retained and that competitive transportation was necessary for that purpose. As a result, after years of agitation and pleading that had been unheeded, the essential capital was miraculously acquired and in 1877 the aging Charles Napoleon Bonaparte Evans was honored and rewarded with the honor of lifting the first shovelful of dirt for the construction of a narrow gauge railroad to run from Milton to Sutherland on the Richmond and Danville line. This was the dawn of a new day and it did not pass unnoticed in the press, which commented:

Since the building of the Milton and Sutherland Road has become established fact the town that once was considered finished begins to look up. People are immigrating there. New houses are being built. A bank is soon to be established. Property holders are beginning to build dwelling houses. This is one way of how it works.

And in the spirit of this appraisal Milton acquired a new lease on life. The tobacco industry was saved, at least for the time being.

Despite the improvement in transportation, problems still existed in connection with tobacco. [55:31] appeared on the road paid to draw for other tobacco markets and particularly against the Milton market. Price competition was keen, as indicated when the resourceful Evans had his fictitious creation, Jesse Holmes the Fool-Killer, write to the Chronicle that he everlastingly wore out a planter who took in his tobacco on the Milton market, carried it elsewhere, and got a third less for it.

However, these and other minor problems failed to discourage the tobacco enthusiasts, for 2,000,000 pounds of the weed was sold on the Milton market in 1880 and there were at least four tobacco manufacturers operating in the town. The farmers were actually stimulated by the fact further that the sale of 30,000,552 pounds on the rival Danville market the same year took place and they planted larger crops than ever. Plants were still being set out in June of that year, when the cautious Evans warned the farmers that it would be more profitable to plant corn as enough tobacco was already in the ground. According to custom this advice went unheeded, and as a result the improvident farmers were forced to buy food and forage at high prices, which they blamed on the railroad freight rates. When this occurred the sagacious Evans printed a blunt rebuke:

The railroads are now feeding this tobacco country, furnishing us with nearly all that we eat, bacon, corn, and flour, and but for them dumb brutes would be on very short rations two thirds of the year. Stop abusing the railroads.

Nevertheless, tobacco acreage was not decreased.

The claim has been made that at one time Milton’s population approximated 1,500 people, but this assertion has neither been substantiated nor disproved. The national census of 1880, the first to list the population of towns, gave Milton 613 people. In the ensuing decade this figure increased to 705, probably because of improved transportation facilities and despite the overproduction of tobacco. In 1889 one manufacturer in the town sold 224,000 pounds of his product and business improved in general, regardless of the fact that in the same year eighteen manufacturers in Danville sold 7,000,000-odd pounds, four in Reidsville 8,000,000-odd pounds, twenty in Winston 8,000,000-odd pounds, and Durham’s four accounted for 4,500,000 pounds of smoking tobacco. This contrast might ordinarily have been discouraging, but business was improving in Milton and tobacco was still king.

There were other concrete reasons for the confidence of the economic situation prevalent in the Caswell town. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the Atlantic and Danville Railroad, first known as the Norfolk, Danville, and Franklin Road, was constructed and it ran through Milton. At long last there was a real railroad in the county and in the same period the long desired toll bridge spanning the Dan at Milton became a reality. Never had the town been in a better position to diversify its economy and the visional Evans promptly recognized this opportunity with a prophecy:

Milton has taken no false growth since the war. It has improved slowly but perceptibly, we trust a sure growth. Her businessmen have remained substantial and their credit unimpaired. But Milton as a water power is bound to develop solid results in less than ten years. There will be mills and factories and railroads will be running along the fine Dan River bottom. It’s bound to be. Nature invites it.

The water power praised by the editor was a natural resource to which Milton had equal access with Danville, and textile mills were dependent upon it. In 1882 three

cotton factories were organized in the Virginia town, financed largely by earnings accumulated in the tobacco trade and other local enterprises, while the Miltonians continued to focus their interest on the growing demand for tobacco. There was sufficient capital in the Carolina town, also accrued from tobacco profits, to finance new enterprises and utilize the abundant water power, but none of it was used for such a purpose. Why invest money in speculated ventures such as textile mills, the Miltonians reasoned, when they already had a prosperous and growing tobacco industry? Thus the possible development of their natural asset was disregarded and this proved to be a tragic mistake. Had the town seized this opportunity while it was useful, it might have safeguarded its future with a variety of industries and become a commercial center of distinction, but tobacco was king and only one head could wear the crown so the water power remained undeveloped.

While the ideas of Evans were being ignored by his overconfident associates, a tiny cloud was forming on the horizon which would increase in size and blot out Milton’s rainbow. The American Tobacco Company was organized in 1889, and the means by which it speedily gained control of the tobacco industry have been related in such detail by Miss Tilley that they need no repetition here. The independent manufacturers of the commodity soon succumbed to the ruthless onslaught of the giant corporation, and one by one the factories in Milton, as almost everywhere else, were forced to close their doors. With the elimination of these buyers, the town’s tobacco market could no longer operate profitably and the warehouses were forced out of business. The king was dead and no crown prince had been reared to occupy the throne.

This economic disaster did not take place overnight, but when the ultimate outcome became clearly discernible no effort was successful if indeed it was even made to unite the town in the promotion of new commercial enterprises. Instead, the dazed citizens ruefully watched their population shrink to 419 in 1910 and then slide steadily downward to the present figure of 235. Tobacco was gone, and the general opinion was that nothing would ever take its place. The county continued to grow the weed, but it was sold in other markets and the profits spent in other towns. Consequently, mercantile establishments shrank in size and number while many citizens, including most professional men, moved elsewhere. Those who remained continued to watch in bewilderment as the town declined from its former importance to a small residential community. Caswell County fared little better, for it failed to be warned by Milton’s plight. Its farmers continued the concentration on tobacco until the county income from its sale dropped one year to $135,000 and agricultural agency officials declared Caswell was sick of its own child, tobacco.

Happily, the economic situation in the county has improved somewhat, but Milton has changed very little. Today its business section is composed of a few old fashioned stores, a service station, and a post office. The rambling wooden hotel rented by textile strikers from Danville during the 1930s shortly thereafter burned to the ground and became another memory of bygone days. A few buildings from the affluent period remain and are dispersed among more modern residences. The tracks of the once vital railroad become a little more rusty with each passing year, and though a paved highway runs into the town over a toll-free bridge spanning the Dan, a comparatively small amount of traffic flows over its hard surface. Miltonians cherish

their more glamorous past but seem completely apathetic to any possibility of future growth and development. The town is not dead; it’s simply standing still, a shadow of its former self.

In summary, Milton’s first major economic setback was the failure to have either the North Carolina Railroad or the Piedmont Railway routed through the town. While railway transportation was in its infancy, had the citizens built fewer tobacco warehouses and financed their own connecting road, as they eventually did, much of the diversified industry which the town had attracted might have been retained and even enlarged. Competitive transportation facilities would have been available earlier which might have enabled Milton to enlarge its tobacco market to such an extent that losing the support of the independent manufacturers would not have wrecked the market. In the second place, when the railroad was finally in operation and business improving, the failure to invest in textile manufacturing and other enterprises by harnessing the water power of the Dan was a tragic mistake. With rail facilities, abundant water power, and population increasing, Milton might have been the home of one of the large tobacco factories which were built in Reidsville and elsewhere and a site of cotton mills which might rival those which have made Danville famous. Who knows?

Lastly, and hardest of all to believe or understand, is the spirit of hopelessness that apparently prevailed after king tobacco died. The town was severely crippled but not mortally wounded, but ideas and plans to promote new enterprises and subsequent growth either were not forthcoming or they failed to mature. However, the citizens should not be judged too harshly for their lethargy. They had hitched their wagon to a star and though it zigzagged back and forth they faithfully clung to it until finally it fell.

Then they could conceive of no substitute for their fallen idol and they remained bewildered by their altered circumstances. Traces of this attitude are still discernible today, but there is also evident a note of pride among the citizens in the fact that their town did survive its tribulations. Possibly someday innovations will develop and Milton will again rise in importance, although it seems most unlikely that tobacco will be the cause of this revival. Thank you. [Applause] [Pause]

John Ellen:

Professor Stokes will entertain questions if you have any, so I throw the floor open to questions.

Durwood T. Stokes:

I thought he said submit to questions but I guess it’s the same thing. Anybody have a question, I’ll try. I guess you’re back there. I can’t see anybody. [Laughter] Yes, sir?

Questioner One:

I thought he said submit to questions but I guess it’s the same thing. Anybody have a question, I’ll try. I guess you’re back there. I can’t see anybody. [Laughter] Yes, sir?

Durwood T. Stokes:

Yes sir, they were, and this was the period when Evans was trying in his newspaper to get them to take another attitude. Of the hundreds of issues of that paper that he must have published in half a century, only sixty-five are still in existence and from that small amount we can see so many statements he made along this line that if we had the whole file it might have been a really interesting effort which he made, but it was not heeded. As long as things were good at hand they didn’t seem to worry about what other folks were doing, not even when Milton was bragging about its 2,000,000-pound-sale in the same year Danville sold over 30,000,000. One reason, I think--it’s a little difficult to determine this exactly--is that the capital in Milton was concentrated in a fairly small number of hands. They owned the tobacco factories, they

owned large tobacco farms, and they were doing all right for themselves for the time being so they just didn’t worry about any other possibility. As they will tell you there today, they put all their eggs in one basket and then dropped the basket. I don’t know whether that answers your question or not, but that’s as close as I can come to it.

Questioner One:

Yes, sir, I think that does help, your idea about the capital being in just a few folks’ hands [1:10:11]

Durwood T. Stokes:

Well, in support of that, if you go to Milton today there are some charming people there. I have some real good friends in Milton. [In a] conversation with one they make no reference at all to what their town might do. It’s what their town did once upon a time. That’s all they want to talk about, sort of like my grandfather was about the Confederacy. He never finished talking about that until he died, and they’re still talking about Milton’s glorious past with the tobacco market, tobacco industry. It’s difficult to understand. I can’t say exactly why this attitude is the one they had but it certainly was there and it’s not completely dead yet. Yes, sir?

Questioner Two:

Is not that an attitude you find in a lot of small country towns clear across the country [1:11:08] North Carolina or South Carolina but all the across the country you find that attitude in many small country towns.

Durwood T. Stokes:

Durwood Stokes: I think very likely so. Let me explain my part on this program there, in case anybody doesn’t understand it. A mention was made in the beginning about all the experts on tobacco history. I’m not one of them. I’m not a tobacco historian. I’m just supposed to be an expert on the town of Milton because nobody else ever got interested enough in it to, [Laughter] to be that, but I think that’s true. Yes, I think we could cite examples and maybe not pin it on tobacco. In some other places it

might have been a cotton mill which got outmoded and they wouldn’t turn it into rayon or something and so you’ve got an empty factory there today. There’s a great deal of puzzle too about just how big Milton actually was one time. Tradition certainly gives it--pretty substantial tradition too--over 1,500 inhabitants and a really substantial amount of diversified industry there at one time. But I only based my paper on just what I could actually substantiate, so I don’t know, but I do know the population rose several hundred from 1880 to 1890 and then it started going downhill again.

Questioner Three:

Dr. Stokes, what year did you say that the Chronicle started under Editor Evans?

Durwood Stokes:

I think I said 1840

Questioner Three:

Was he a native North Carolinian?

Durwood Stokes:

He was born in Norfolk County, Virginia, and moved to this state when he was a young man. He worked for Dennis Heartt in Hillsborough, the Hillsborough Recorder, and the Raleigh Register, and two or three print shops to learn the printing business. Then he went to Greensboro when Swain died and he was a relative of Swain’s widow and edited the Greensboro paper for some time and then he went over to Milton and bought the Milton paper and established it as the Chronicle. He was a newspaper editor far above many of his day. He was a cousin of William Sydney Porter, O. Henry. In fact, O. Henry wrote one of his short stories that’s in the collection of Voice of the City I believe, based on Evans’s fictitious character, Jesse Holmes, the Fool-Killer and he named it “The Fool-Killer.” This Holmes was a character Evans invented who once a month would write a letter to the editor and his business in life was going around with a club hitting fools over the head and he told

why. He stayed awful busy. [Laughter] Evans used this way to bring out political criticism. In fact, he said the Fool-Killer went to Raleigh once and went to see Governor Holden, who jumped out the window when he saw him coming.

Questioner Three:

Thank you.

Durwood Stokes:

Just one more thing, since you started me on Evans, he died in the North Carolina Senate, a member of the senate, and Caswell County might have sent him to that august body profitably many years earlier than they did, but they finally did and he was still working to improve things for his county and went home for the weekend and caught cold on the train, on the railroad, and died of pneumonia from it. But he edited that paper just about fifty years. [Laughs] If I can’t answer them I can sidestep them anyway. [Laughter] Any other questions? Speak out because I can’t see you.

Questioner Four:

What is the present day situation in Milton on tobacco? Are they still raising it there in that area?

Durwood Stokes:

Well they raise it in Caswell County, but not particularly in Milton. Milton’s just a residential town today. The mayor of the town lives in Milton and runs an oil business in Yanceyville. [Laughter] Some of them work in Danville, teach in the county schools; that kind of thing. It’s a beautiful place and work has been done for historic preservation there for the few remaining old buildings that are left, which show that it was very affluent at one time. It’s just a pleasant little residential town that’s bypassed by most civilization. You know when Bob Scott had never been

there until 1971 it’s not on the main line of traffic at all. [Laughter] I think I saw a hand over--. Just speak out. I can’t see you.

Questioner Five:

Were there any attempts by Danville businesses to found branch offices in Milton after the Civil War?

Durwood Stokes:

Yes, but it did not amount to much until this railroad was acquired there. The whole thing that was holding Milton up was it was not in on the competitive transportation, but it could have been. The only way they ever got on it was to build a railroad and pay for it themselves, and had they done it thirty years earlier the picture might have been very different, but they were making money on tobacco and they just kept sitting and waiting for something to happen. It was only when they got desperate that they raised the money to build the railroad to connect to the main line.

Questioner Five:

I had thought there was some evidence that Sutherland, of the railroad fame, had opened a number of stores there, and finance companies and insurance companies?

Durwood Stokes:

Oh, he did along in the period when it was reviving after they got the narrow gauge railroad. He’s the one that furnished the principal enthusiasm and good deal of capital for that road, did a great deal for Milton, but they simply did not take advantage of the opportunity sufficiently. At the time Sutherland was working with Milton, Milton had ample opportunity to revive to a greater extent than it had ever been before, all this water power there, its tobacco business all right, but it could have diversified its industry and become quite important, but they simply took no interest in it, and about that time Evans died and he was the chief prodder of the conscience of the

people, I think and he couldn’t move them beyond a certain point. Was there another hand over here? Yes?

Questioner Six:

Was there any kind of description of religious antagonism to tobacco or any rumor of a health menace?

Durwood Stokes:

Not that I ever heard of, not in Milton.

Questioner Six:

Or in the community?

Durwood Stokes:

I don’t think there is even yet. [Laughter] Because they still think tobacco is the golden weed in more ways than one. They’re broad minded about it though. They’ll admit Milton played a long shot and lost. They don’t seem to be bitter about it, and not interested in doing anything else about it either. [Laughter] It’s not dead, it’s just asleep, and they don’t seem to want to wake up. But it’s a nice, pleasant residential community, a nice place to retire to. It’s peaceful and quiet. I never found but one place more quiet and that was down at Hatteras one summer. [Laughter] Before they built a road. I don’t think there was any antagonism of that kind at all.

Questioner Seven:

Dr. Stokes.

Durwood Stokes:

Yes?

Questioner Seven:

I get the impression that what you’re saying is that tobacco as a good cash crop was somehow at fault here. Weren’t the people really victims of circumstances beyond their control: the American Tobacco Company, the Civil War, the railroad, and that sort of thing?

Durwood Stokes:

Well they were in some ways but if they’d had sufficient diversification they might have survived industrially.

Questioner Seven:

[If it hadn’t brought] quite so good a price they might be better off today, is what you’re saying.

Durwood Stokes:

[Laughs] Well as to that, I don’t know. But other cities, towns, lost their independent tobacco manufacturers and still were able to maintain their markets. They had other things to fall back on. Milton simply got to the point where its population couldn’t survive. When 300 out of 700-odd people in ten years move away from a town, it’s pretty significant if there’s not much being down there to provide employment or develop anything, and that’s what they did. I think the trouble is not that they couldn’t do well with tobacco. They did too well with it and they didn’t want to do anything else.

John Ellen:

Thank you. We’ll have a short break for a coffee break and reconvene about 11:15 for the second paper. Thank you.

END OF RECORDING

Transcriber: Deborah Mitchum

Date: October 8, 2010