William Ruffin Cox

WILLIAM RUFFIN COX

Secretary United States Senate

A Sketch of the Life and Services of

General William Ruffin Cox

Length of days is the scriptural recompense for the consecrated service of mortal man, and surely the subject of this sketch is richly entitled to heirship of the promise contained in the divine proclamation—“That thy day may be long in the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.”

William Ruffin Cox was born at Scotland Neck, in the State of North Carolina, March the 11th, 1832. His earliest American ancestor on the maternal side was Captain Nicholas Smith, emigrant from England to Virginia and member of the House of Burgesses from Isle of Wight County, in 1664. His first American ancestor, on the paternal side, was John Cox, an Englishman, whose birth is recorded in St. Paul's Cathedral in the city of London, and who served his native country well, before he left England's shores. He was an efficient officer in the British Navy.

Emigrating to the new world, he settled in Edenton, North Carolina—an old, aristocratic locality, and there he married into the distinguished Cheshire family. His energy was conspicuous in the American Merchant service of the War of 1812, and his duties hazardous. Indeed, his fleet vessel, in a crucial moment, could not escape the British cruisers, and he, himself, was taken prisoner. This, however, was but an episode in the useful life of John Cox.

His eldest son, Thomas Cox, was born in Chowan County, North Carolina, but later removed to Washington County, and still later to Halifax County, where he married Olivia, daughter of Mormaduke Norfleet, a wealthy planter, and descended from good Virginia as well as North Carolina families.

Thomas Cox was a prominent and prosperous merchant and a conscientious and useful citizen. He traded extensively with

the West Indies and with the Northern States. He was a leading politician, and represented his county in the Senate in 1823. Agriculturist and merchant, he was also a seer who felt the great necessity for railroad communications, and he was a pioneer in their construction through North Carolina. He died early and his widow removed to Tennessee, and there her best efforts were devoted to the rearing of her children, the youngest son of whom was William Ruffin Cox.

His earliest training was at Vine Hill Academy, at Scotland Neck. After his removal to Tennessee, he attended a preparatory school near Nashville, and at the early age of fifteen, entered Franklin College, where he graduated with distinction; then studied law at Lebanon College, and came to the Bar in 1852 in the City of Nashville. There he formed a partnership with a well known lawyer, John G. Ferguson, and they practised successfully together until 1857, when he married, returned to North Carolina, and with much zeal, began to cultivate his lands in Edgecombe County.

His ability and energy would not be confined to the acres of his large estate, and two years later he went to Raleigh to practice law, entered with much interest into the political and economic life of the State, and at the same time superintended his plantation.

Momentous times were stealthily advancing, which were to call forth latent qualities in the character of William Ruffin Cox. He saw into the future, and began to prepare for the grim emergency of war. Forthwith, of his own means, he equipped a light battery, and subsequently recruited a company of Infantry. The Governor of his State, realizing his will and ability, his genius to command and inspire, appointed him Major of the Second North Carolina Troops, and the remarkable military service of William Ruffin Cox began.

After six months’ experience, he was put in command of heavy artillery at Pratt's Point, on the Potomac River, and in

June, 1862, his regiment (the Second North Carolina), was the first to cross Meadow Bridge at Mechanicsville, under terrific fire. The next day, as all of the field officers had fallen, Major Cox led this gallant band into the “Seven Day's Battle,” so famous in the annals of war. His courage was conspicuous, and his endurance almost superhuman in the heroic effort to beat McClellan back. At Malvern Hill he was severely wounded, and did not join his regiment until after the Battle of South Mountain.

Again, at Sharpsburg, his courage was remarkable; Colonel Tew there fell, Colonel Bynum was promoted to the vacancy, and Major Cox became Lieutenant Colonel. After the battle of Fredericksburg, Colonel Bynum resigned and Cox took his place.

At Chancellorsville, Colonel Cox displayed wonderful coolness and military ability, and his regiment was one of the sixteen North Carolina regiments that Jackson led across Hooker's front. Cox, fearless and assured, with unusual skill, drove the enemy from their works and actually mocked, with wonderful endurance, the five wounds that he had received. Ramseur in his famous report, called him “The Chivalrous Cox, the accomplished gentleman, the splendid soldier, the warm friend, who fought in spite of five bleeding wounds, till he sank exhausted.” And the immortal Jackson sent through Robert E. Lee, a message of appreciation to the famous brigade.

At Spottsylvania, William Ruffin Cox and his gallant brigade won undying fame by their reckless intrepedity in driving the enemy from the Bloody Angle, after twenty-three hours of conflict, for which brilliant achievement the command was praised both by General Lee and by the Corps Commander, Lieutenant General Ewell.

Soon after this, Ramseur received his commission as Major General and Cox led the brigade which had won its spurs for courage and ability.

General Cox was with Early in the Valley Campaign, and the movement to Washington, and his brigade has the distinction of being the nearest to approach the National Capitol.

From his dramatic experience with Early, General Cox was called to aid Lee at Petersburg, where he was placed in command of two miles of front under this immortal chieftain, and again he received the highest commendation for his conduct. It was at Sailor's Creek, when Lee was overwhelmed with apprehension, that Cox's brigade cheered his sad heart.

At Chancellorsville, stoical endurance and five wounds; at Spottsylvania, greater endurance, remarkable courage and promotion: Finally—Petersburg to Appomattox! In the tragic demoralization of this ghastly march, soldiers struggled along almost bewildered, many falling out of ranks half dazed. The enemy, fully equipped and intoxicated with victory, rushed on, and the Confederates made a stand to save the trains.

On April the ninth, the pitiful remnant of the Army of Northern Virginia, after six days of retreat and continuous fighting, reached Appomattox. Could it cut through the Federal Army there? Could it get food from Lynchburg and retreat southward? Could it have done this even if its brave way had not been impeded by a cumbrous wagon train?

Gordon's Corps in front, and Longstreet's Corps in the rear, awaited the signal for a general advance, the cavalry already skirmishing right and front. Grimes was called to another part of the field, and General Cox was put in command of the Division. General Gordon ordered him to throw forward up the slope of the hill. He obeyed with celerity, and the impetous color-bearers bore their flags too far forward. Soon Cook's and Cox's Brigades received a terrible artillery fire from a battery in front. Nothing daunted, they advanced, charged boldly and captured it.

The Federal calvary attacked fiercely, but unsupported by the infantry it had to retire.

General Cox discovering that the woods in front were full of troops under General Ord, took a commanding position, and ordered a halt. Presently columns of infantry bore down upon the flanks and center of the division and the firing was resumed.

Couriers from Gordon ordered the withdrawal of the division, and this was ingeniously accomplished.

The Federal Army, conscious of the movement, advanced so rapidly that the situation became alarming. This advance must be checked. How?

General Cox at once ordered the regimental commanders to meet him at its center without halting the command, which was done. He then pointed to a hill between them and the enemy and ordered them to face about double quick to the crest of the hill, and before the enemy could realize their action to halt and fire upon them by brigade, then with equal rapidity, to face about and join the division in retreat.

With a wild rebel yell Cox's Brigade swiftly and precisely obeyed the sharp command, “Halt, Ready, Aim, Fire!” And the last shot at Appomattox was the immortal verdict of Cox's Brigade, which safely withdrew and rejoined the division.

“Gallantly, gloriously done!” was the salute of General Gordon, and although the white flag of surrender waved, and a noble cause was lost, to the brigade of General William Ruffin Cox is due the credit of the last charge at Appomattox of firing the final shot.

Most of us remember the description of this romantic and chivalrous episode in the “Sunset of the Confederacy,” by General Morris Schaff, of Massachusetts, (page 210) “Grimes put Bushrod Johnson on his right, Cox's Brigade of North Carolina holding the extreme flank. (Page 222.) As Chamberlain crosses the little run, all the troops on his left press forward and the whole Confederate line, now full of despair and heartache, begins to fall back. But as they return, Cox gives to his North Carolina Brigade the command, “Right about face!” Behind them their young, stately, commander stands, his body bearing the scars of eleven wounds. As one they whirl. Firmly rings his voice again: “Ready! Aim! Fire!” and from level guns pours the last volley that will be fired by the Army of Northern Virginia. Manly

was he in the morning of life; manly is he in its evening; and his heart still youthful nothwithstanding its weight of seventy odd years. Here is my hand gallant Cox, and may your last days be cloudless and sweet!

“And reader, while the smoke of his brigade is billowing up, let me tell you a monument marks the spot where that last volley was fired; and, if ever you visit the field, and I hope it will be in October, do go to that stone; the tall, slender, gray-bodied, twilight holding young pines that have grown thickly in front of it, and the purple asters blooming around it, if you lend your ear, will welcome you to its proud record.”

All was over, and General Cox and General Lee were standing together at the bier of the Confederacy.

“Where do you intend to go?” General Cox asked General Lee.

“I don't know, I have no home.” Was General Lee's reply.

No home, when so many thousands held him dear!

The experience of war did not weaken the energy of General Cox. He turned his attention to the healing and reconciling work of peace, and he soon adjusted his mental attitude for a strenuous life, realizing that whether in peace or war it is always “fight!” He immediately established himself in Raleigh, and began to practise law, but his executive ability, his calm judgment, his keen foresight and philosophy were rare qualities which made him essential to the public life of his State. His first official position was President of the Chatham Coal Fields Company.

In 1865 he announced his candidacy for Solicitor of the Metropolitan District, and although the State then boasted of a Republican majority of 40,000, he won the race by 27 votes. He was then the only Democrat in North Carolina to hold a public office. In 1873 he was made Chairman of the State Educational Association, and rendered inestimable service in that position. In 1875 he was Chairman of the Democratic State Executive

Committee, and in 1876 he was a leading favorite for Governor, but declined to run against Vance. Instead as Chairman of the Democratic State Executive Committee, he led the most brilliant campaign for victory ever fought in North Carolina, resulting in the overthrow of the miserable carpet bag rule, and in a Democratic majority which made him the peace hero of his State.

He was delegate at large from the State to the National Democratic Convention in New York, which nominated the Hon. Horatio Seymour for President of the United States. At the next Presidential Campaign, he was tendered the appointment of delegate at large to the Convention at St. Louis, in 1876, but declined. In 1877 Governor Vance appointed him Judge of the Metropolitan District, and the wisdom of his appointment was fully justified by the career of Judge Cox on the Superior Court Bench.

“As a Judge his dignity and urbanity, and his fine culture, no less than his efficient discharge of his judicial functions, and the fairness and impartiality with which he tried the cases brought before him, gained him an enviable reputation.” (Biographical History of North Carolina, Ashe—Vol. I, p. 234.)

He resigned this position to canvass for nomination to Congress. Up to this point as peaceful and accomplished planter, as brilliant soldier, as Democratic Chairman of his State, as able lawyer and jurist, the career of William Ruffin Cox was honorable and constructive; now elected to the 47th Congress of these United States he must measure his lance with nation-wide political giants. His career in Congress was strikingly brilliant.

Three times elected to Congress, he served on most important committees, notably on that of Foreign Affairs and Civil Service Reform, then in its infancy. His declaration that “Civil Service Reform is the essence of democracy” will ever survive as a National legend.

In the pivotal campaign of 1875, the main issue of which was to save North Carolina from negro rule and the detestible

carpet-bagger, his energy was marvelous, and his famous telegram, “Hold Robeson and save the State,” is a slogan for devotion and action. It will ring down the ages as a homely but imperative cry for justice and relief. General Cox ever warned his fellow citizens against overconfidence and apathy, and one of his fine aphorisms is “Organize and do; do not rely on boasting; don't speak until victory is ours!”

He had religiously fought for a just and uncompromising ballot, and had given his best powers for the establishment of a free and unpurchasable rural population.

In 1892, General Cox was elected Secretary of the United States Senate, an office which not only required decided ability, but also tact, exactness and diplomacy; all of which essential qualities he brilliantly displayed, and his friendships extended all over the continent. He enjoyed the unique distinction of being Secretary of the Senate under both Democratic and Republican Presidents.

The popular reception of the nomination of General Cox for election and re-election to Congress is thus expressed through contemporary papers.

The News and Observer, of Raleigh, declared, “If this is the post of honor, I submit that this honorable position is due to that distinguished statesman and accomplished gentleman, General William Ruffin Cox, the present representative from the Fourth Congressional District. General Cox entered the army at the commencement of the war, and only ended his connection with it at Appomattox Court-House, bearing with him to his home a number of wounds inflicted in his arduous service in defence of his country.

“On the bench he was an upright and just expounder of the law, never letting his personal preference influence him in the least where justice and right were opposed to him. But a debt of gratitude is still due him by the people of North Carolina for his invaluable services as Chairman of the Democratic Central

Committee for saving the State by electing a majority in the State Constitutional Convention. Who can estimate the woes unnumbered that would have befallen us, our children and our children's children had not ‘Hold Robeson, and save the State’ been flashed over the wires? His arrest and the indignities he suffered at the hands of the authorities is another debt yet unpaid by the people of North Carolina. I ask, therefore, in the name of the people, that all candidates withdraw in favor of this distinguished son of North Carolina, and let us unite as one man, and nominate him by acclamation.”

Again the press declares “The re-nomination of General William Ruffin Cox was the right thing done in the right way. General Cox deserved the honor bestowed. He is a faithful and able man, and is now in the flower of his usefulness. A man of very decided ability, a sound Democrat, having considerable experience in public life, and almost unbounded energy, there is a fine field before him. He is very popular, the District will easily re-elect him.”

And yet again the press of North Carolina rejoices. “The nomination of General Cox for re-election to Congress yesterday by acclamation was a high and merited compliment.

“General Cox has borne himself in Congress, as he has on every field where duty called him, like a chivalrous gentleman, a sterling patriot, a staunch Democrat, a representative North Carolinian. The Metropolitan District tenders him its sincere acknowledgment of his devoted services, and again entrusts to him that banner, which he has borne so bravely in the past. That he will carry it to victory, no one doubts.”

In reviewing the life of General Cox, it may be truthfully recorded that in his formative years he was an earnest student and a merry comrade, although, even then, he vaguely heard the “Call” of life. In war he was intrepid, cool, resourceful, and eleven wounds testify to his courage.

On the bench he was upright, unbiased, clear; eliminating always both preference and prejudice; as Chairman of the Democratic State Executive Committee he really saved his State.

Interlaced with his most conspicuous efforts, and urgent official labors was earnest action for the alleviation of his people. He was Chairman of the Committee which established the North Carolina Journal of Education, and his advice and counsel influenced the adoption of many vital economic and political improvements.

His wide and dramatic experience, together with his fine memory and gift of speech, made him the especial orator on many occasions. His most notable orations are the “Memorial Addresses upon the Life and Services of General Stephen D. Ramseur, General James H. Lane and General Marcus D. Wright.”

He was orator of the day at Oakwood (Richmond, Va.) Memorial Services, at Memorial Day at Winston-Salem and at Durham, North Carolina. He has also delivered fine orations before the U. D. C. at Tarboro, at the laying of the corner-stone of the North Carolina Masonic Temple in Raleigh, at the exercises in memory of John H. Mills, founder of the Oxford Orphan Asylum, at the University of North Carolina, at Trinity College, and at the Mecklenburg Declaration Centenary, when he took the place of General Joseph E. Johnston as Chief Marshal and Orator.

“His address at the Centennial of the Mecklenburg Declaration was remarkable for its broad and lofty patriotism, and in all of the many important addresses, which he has delivered, he has sought to enforce the most enlightened public action, and to instill a love of country, and an abiding faith in humanity.” (Biographical History of North Carolina, Ashe—Vol. I, p. 235.)

With his gift of oratory, he possessed a clear and distinct style, and his contributions to newspapers and magazines always

exhibit a calm vision and a sound judgment, which render them helpful and compelling.

General Cox was Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Masons of North Carolina, to which office he was elected in his absence. He was also for years trustee of the University of the South.

Like a golden thread running through politics and public life generally, in the heart of General Cox was the love of the soil. He was for some time President of the North Carolina Agricultural Society, and his leadership reacted most happily on the land of his State.

Added to his almost superhuman activity was a firm loyalty to the Episcopal Church, of which he was long a vestryman in Christ Church, Raleigh, and was often delegated to its Conventions.

Of an imperious and compelling nature, General Cox also possessed the heart of a little child, and his attitude to all about him was the essence of affectionate kindness. His spirit soared above the petty cares of life, and on all occasions he was a philosopher.

His plantation flourished under his wise rule, he studied and analyzed the questions of the day, absorbed the best literature, and exerted a salutory influence upon all about him. Age could not dim the activity of mind or body. Life with its perpetual change and problem was always an interesting study to him.

In 1914 his portrait appeared in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, along with the ten (then surviving) Confederate Generals, and it is there announced, “General Cox, by the way, has a distinction never enjoyed by any other Confederate General, his erect form defying age, bears eleven wounds received upon the battlefield.”

In 1918, on his 86th birthday, the North Carolina press comments as follows:

“General W. R. Cox has solved the difficult problem of growing old in years while retaining to a marked degree the vigor and alertness of robust manhood.

“On Sunday, March 11, at his elegant country home, at Penelo, General and Mrs. Cox entertained a few friends at dinner, in celebration of his birthday. The proverbial hospitality of the typical Southern gentleman's home was fully exemplified. * * * The General has been so closely identified with the political life of the State in its most stirring epochs that his conversation is a source of engrossing interest.

“As commanding general of the famous Cox Brigade that wheeled into line at Appomattox with the freshness and precision of the earlier years of the war, as vigorous Solicitor for the Metropolitan District of the State, as learned and able judge of the Superior Court, as Chairman of the State Democratic Executive Committee in that great campaign when he issued the famous order ‘Hold Robeson, and save the State,” as member of the lower house of Congress, as Secretary of the United States Senate, as successful and prosperous planter and man of affairs, and as cultured and educated gentleman, he has met no emergency and filled no position that has not been highly creditable to himself, and of great service to the State. His patriotism is of the most fervid type, and yet it is inspired by his highly intelligent interest in and his wide knowledge of the country's condition. * * * Of the unwritten history of the State, during the Reconstruction period, he probably knows more than any man living at this time.

“Always observant and an omniverous reader of good books, he possesses a fund of information on almost all subjects that is astonishing. Intellectually he is as alert as he was in middle life, and he preserves the handsome features and soldierly carriage that made him a perfect type of the Southern cavalier. His

friends can wish him and themselves no better fortune that that for many years to come he remains as he is, the type of the Old South's best product.”

Doubtless there are other distinctions, quite as unusual, possessed by this indomitable North Carolinian. Be the day dark or full of sunshine, there emanated from him a radiance, a hopefulness, a resignation to existing circumstances, a faith, a humor, which preach a wholesome gospel to a restless and unbelieving world.

The funeral of General Cox in Raleigh, North Carolina, was a touching and wonderful testimonial of the affection and honor accorded him by the people of his State. The Grand Lodge of North Carolina, military organizations, relations and friends, not a few, assembled at Christ Church, where the funeral ceremonies were conducted, then followed him tearfully to his grave.

A splendid portrait of him is the latest gift to the North Carolina Hall of History. “As one beholds it, one sees a gentleman, who, through all his long life, represented the finest things North Carolina has to offer. He is portrayed in the uniform of a Confederate General Officer—1864-’65.” (Col. Fred. A. Olds.)

This sketch would be imperfect without a reference to the physical beauty of General Cox, which seemed the expression of the solidity and depth of his mind. Of heroic statue, perfectly proportioned, his face with its classic chiselling might havs been the face of a Greek or Roman Senator in a romantic and constructive age. The charm of his smile, those who knew him, will ever remember.

Actor in Three Great Scenes

With the possible exception of General E. M. Law, who still defies time from his retirement in Florida, General William Ruffin Cox probably saw more of the splendor and tragedy of the War between the States than did any man now alive.

For General Cox commanded a regiment in Ramseur's brigade of Rodes’ division of Jackson's corps of the Army of Northern Virginia.

That may not be identification to a generation that is fast forgetting old names, but to those familiar with Confederate history, such a command was guarantee of ability, of courage, of fidelity and of service. Ramseur, Rodes, Jackson—they went out together into the wilderness. By night Jackson had fallen, mortally wounded; Rodes was killed in September, 1864, at Winchester, “in the very moment of triumph,” as Early wrote, “and while conducting the attack with great gallantry and skill”; Ramseur conducted a magnificent rear-guard action the next month, October, 1864, and dying, was captured at Cedar Mountain. It would have been enongh to have said of General Cox that he had the confidence and the esteem of these three, his superiors, while he was still a colonel. But it was his high honor to lead his regiment into action when Jackson was directly in rear of Hooker's army, ready to win at the high noon of the Confederacy a victory that stands almost unparalleled in military history. The very thought is enough to fire the imagination: The quiet-faced gentleman who until recently was to be seen on Franklin street many an afternoon had heard with his own ears the bugles call Jackson's charge at Chancellorsville!

Wounded then and denied the high honor of Gettysburg, he was back with the army in the spring of 1864, and, on the old battleground, was a prominent actor in that other great scene of

wilderness warfare, the Bloody Angle. His regiment was still with Ramseur, who was ordered to charge and to dislodge the Federals when the whole of Lee's front was in danger. Ramseur was to have given Cox the order, but was wounded in the arm and had his horse shot under him: Bryan Grimes took his place and sent Cox forward. After the struggle was over, Lee himself said of Ramseur's brigade that the men “deserved the thanks of the country—they had saved the army.”

Once again it was General Cox's distinction to stand out in a great hour of the Confederacy—the twilight hour, this time. The story is so well known as scarcely to need repeating. By hard work and tactful discipline, Cox managed to keep his little brigade in order on the retreat from Petersburg. With one other brigade, Wise's, it marched perfectly. As Lee saw the troops pass—it was probably at the “High Bridge” below Farmville—he asked whose they were, and when told that they were Cox's “Tarheels,” he said with a catch in his voice, “God bless gallant old North Carolina!” A few days later, Cox's troops were among the last to deliver a volley at Appomattox.

Could it have been given to a man of the ’sixties to have shared in three greater acts than those of Chancellorsville, the Bloody Angle and Appomattox? Not unless he had been privileged, as were a few, to remain constantly with Lee from the day he took command in front of Richmond until the guns were parked on April 9, 1865.

Last save two of all the surviving general officers of the Confederate army, William Ruffin Cox was the last of all the generals born in North Carolina. That of itself is a fact that calls for more than passing notice. Virginia cradled the three greatest strategists of the War between the States, barring the wizard Forrest; South Carolina gave the Confederate cavalrymen and corps commanders; North Carolina supplied a notable array of brigade and divisional leaders. In addition to Braxton Bragg, who was a full general, and the beloved T. H. Holmes, who

ranked as a lieutenant-general, North Carolina gave the Confederacy twenty-four brigadier-generals and seven major-generals. Among the latter were some upon whom Lee leaned heavily. J. F. Gilmer was of the major-generals, a brilliant engineer to whom historians owe the best maps of Southern battlefields; Major-General Bryan Grimes was also a North Carolinian, and had the peculiar honor of receiving from a North Carolinian and passing on to another son of the old North State the order to clear the Bloody Angle. Of Hoke, that old war-horse, of Pender, of Ramseur, of Robert Ransom, and of the luckless Whiting, all North Carolina major-generals, it is unnecessary to speak. Without exception their names are written on some of the finest pages of Southern history. Of North Carolina brigadiers, who can forget Branch, or Clingman or Daniel? What veteran does not remember “Jim” Lane and “Mat” Ransom, and Gabriel J. Rains, who might in times of peace have been a mechanical genius? And who does not put on the same scroll J. J. Pettigrew, who led his brigade up the hill at Gettysburg? Gallant was that company; deathless its honor!

—News-Leader, Richmond, Va., Dec. 27, 1919.

Another Link Is BrokenAnother link in that human chain which connects the Old South with the New is broken by the death of General William Ruffin Cox. So rapidly are the famous leaders of the Civil War period passing that soon the old order will have become but a glorious memory, a tradition to be cherished for ever and ever by generations that must learn their history of the South only from its written records. Of those heroes of the War Between the States, who through valiant service achieved the title of brigadier-general, but two now remain alive.

General Cox was typical of the South, of the South's best in strong, self-reliant, independent manhood. Like thousands of others of its young men in the years immediately preceding the war, he saw the clouds gathering over his beloved homeland, and he set about preparing for the breaking of the storm. The first shot at Sumter found him ready, his troops organized, and from that hour to the day when his soldiers, his sturdy North Carolinians, acting under his orders, fired the final volley at Appomattox, he was in active service, fighting, fighting, always fighting, for the Cause he knew was right, but which he was doomed to see defeated. Eleven wounds he bore to the grave, honorable wounds from Northern bullets, scars in which he gloried throughout the long years during which he was spared after the coming of peace. The list of engagements in which he fought, names written in letters of living light, is sufficient evidence of the warrior's role he played—Meadow Bridge, Seven Days, Malvern Hill, Sharpsburg, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Spottsylvania, with its Bloody Angle, the Valley Campaign, Petersburg, Appomattox, what memories they stir, and what a heritage of glory for any warrior to leave!

As he fought for the South on the field of battle, so he fought for it in the dark days of Reconstruction, his ardor and determination

undiminished by the unsuccessful outcome of the armed conflict. Setting his face to the tasks of peace, he took a leading part in the work for his native State. As a judge, member of Congress and as a wise leader in the councils of his party, he did much for the restoration of tranquility and for the maintenance of supremacy of the white race, threatened by the old carpet-bag regime. Had he cared to do so he might have received far higher honors than those he accepted, but he was ever content to work along his chosen lines, caring little for personal preferment, and to his credit be it recorded that his achievements in peace were equally meritorious with those of war. And in his ripe, old age, honored by North and by South, he gave to the service of a reunited country, gave gladly and proudly, two sons, who fought in France under the Stars and Stripes, sons who brought fresh credit and happiness to the aged warrior. Now he has answered the last roll call and passed over the river where one likes to believe that he is reunited with Lee, and Jackson, and Ramseur, and all those other fellow heroes, whose glory even the passing of time cannot dim.

—Richmond Times-Dispatch December 28, 1919.

General William Ruffin CoxBY S. A. ASHE

Permit me to lay a wreath on the bier of General Cox, whose death you have announced. To the present generation General Cox has been largely a stranger, but to the old generation that has nearly passed away, he was familiar because of his works and walk in life.

You gave some inadequate account of his valorous deeds during the war. They bespoke the man. But that struggle on the battlefield ended in disaster. Then came the civil struggle—the efforts of the people to maintain their standard of excellence in life and their aspirations as enlightened civilized beings against the machinations of those who sought to crush us down and to inflict on us the most cruel fate they could devise. In that struggle which was protracted for years, General Cox was a commanding figure, as he had been on the battlefield; and he attained relatively a higher post of honor, and his contributions to the cause were great and important; and, happily, the efforts he then made were crowned with success.

The end to be attained was the preservation of our Anglo-Saxon civilization—to prevent the subjection of the white people to the domination of the untutored population of African descent; and to General Cox and his associates is to be attributed the victory. To them is due the lasting gratitude of every white North Carolinian who has red blood in his veins; and, likewise, the colored people of the State owe to those men grateful appreciation, for they averted race antagonisms and race hatreds that would have been most disastrous to the colored people of our community. Indeed, the happiness and good fortune of both races in North Carolina is largely due to them.

While there are still living a considerable number of those patriots, like Major John W. Graham, of Hillsboro, who participated

actively in that long and arduous struggle, yet General Cox was the last survivor of the more active and conspicuous leaders in that great and important crisis. Governor Graham, Governor Bragg, Governor Vance, General Ransom, Judge Ashe, Judge Merriman, General Barringer, Colonel Saunders, Governor Jarvis, R. H. Battle, and their associates, have gone to their reward. It was General Cox's fortune to survive them. He was the last of that group of distinguished men who cooperated in their efforts to avert the calamities that threatened the State.

It so happened that he was elected by 27 majority as Solicitor for the Raleigh District, in 1868, and luckily he was allowed by the military officers in control to hold office. That was a most important position at that crucial time; and General Cox performed its duties so wisely and acceptably that he contributed greatly to the attainment of the ultimate object of the Conservative people of the State.

Year by year, and step by step, the Conservative people were brought into harmony and more compact association, and confidence established among them, until eventually, in 1874, General Cox, being then the chairman of the Conservative State Executive Committee, we carried the State by some fourteen thousand majority.

The next year was an election for delegates to a constitutional convention to amend the constitution. As the returns came in it was apparent that the control of the convention was in doubt. The election in Robeson had been attended with irregularities. Its vote in the convention would be determinative. General Cox's dispatch to the chairman of the Robeson county board has gone down in history: “Hold Robeson and save the State.” It so resulted—for certificates were given to the Conservative candidates, whose election made the convention a tie. And when the contesting Republican candidates claimed their seats, such developments were made before the committee appointed to investigate the election, that they voluntarily abandoned

their claim of election and retired from the contest, allowing the Conservative candidates to retain their seats; and so, the organization of the convention was obtained by the Conservatives. The next year came the final contest of supremacy between the parties—the decisive year of 1876. As the convention drew near, the popular acclaim throughout the State was for General Cox for Governor. But at a late hour, Vance, who had theretofore abstained from being a candidate before the people, indicated that he would accept the nomination, and Cox, as gallant in peace as in war, effaced himself, and Vance was unanimously nominated; and Cox continued to serve as the head of the party; and his wise administration was rewarded by a majority of 18,000 for the ticket at large, although Vance's majority was only about 12,000. That was the end of the great struggle. North Carolina was saved from the perils that had threatened her. The future was secure. Cox's brow should always be adorned with imperishable laurels.

I feel that it is a great privilege to be able to pay this tribute to General Cox.

I was closely associated with him during that period, and afterward, not only in political work, and at the bar, but in the vestry of Christ Church, of which we were long members. Our friendship was cordial and close. In all the relations of life, he was a man of sterling worth—a gentleman of the first water; a man whose integrity was without a blemish; a wise man, whose soul was ever courageous. And he rendered the people of the State a great service, whose benefits will remain to our posterity throughout the ages.

All honor to his memory.

—Raleigh, N. C., News and Observer, December 28, 1919.

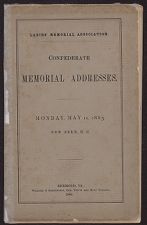

Portrait of General Wm. R. Cox is Presented

to North Carolina

ADDRESS OF PRESENTATION OF PORTRAIT, BY HON. FRANK S.

SPRUILL, OF ROCKY MOUNT, N. C.

The memory of General William Ruffin Cox, commander of the North Carolina Confederate troops, who made the farthest advance on Washington, commander of these troops again when they made the last charge at Appomattox, and chairman of the Democratic Executive Committee in 1875, when the State was redeemed from carpet-bag rule, was honored yesterday when his portrait was presented to the State of North Carolina and accepted, to be placed conspicuously in the Hall of History.

Before an assembly that filled the Supreme Court room, and with Bishop Joseph Blount Cheshire presiding, Mr. Frank S. Spruill, of Rocky Mount, presented the portrait on behalf of Mrs. Kate Cabell Cox, widow of the late General Cox, and it was accepted by Chief Justice Walter Clark, of the North Carolina Supreme Court, for the State.

The portrait, a three-quarter-length likeness, is the work of Mrs. Eliphalet F. Andrews, a well-known artist of Washington, and is declared to be a splendid likeness of General Cox, attired in the uniform of the Confederacy, with figures of Confederate soldiers about a camp-fire in the hazy background.

In addition to the members of the immediate family of General Cox, the exercises were attended by a number of State officials, Confederate Veterans and distinguished North Carolinians.

The speaker, with sympathy and appreciation, discussed the life of General Cox on his plantation where, with the introduction of the best and most scientific methods of farming, he exercised a salutary influence on the entire country about him.

—News and Observer, Raleigh, N. C., February 28, 1921.

GENERAL WILLIAM RUFFIN COX

Army of Northern Virginia, C. S. A.

Address of Presentation of Portrait

By HON. FRANK S. SPRUILL, of Rocky Mount, N. C.

Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen:

I am commissioned by Mrs. William Ruffin Cox to present to the State this portrait of its distinguished son, and to speak briefly of his illustrious career and great achievements.

I approach the performance of this pleasing task with cheerful alacrity, for chronicler has rarely had a richer theme.

The records of history are more and more becoming pictorial. Posterity, reading of the high deeds of some dead and gone soldier or statesman, naturally desires to know what manner of man he was. In the absence of portrait or likeness, imagination often supplies the details, and, if his career has been one of great deeds and knightly prowess, we think of him as one

“ . . . like old Goliath tall,His spear an hundred weight.”It is meet that we should hang upon the walls of the State's Hall of History portraits of the men who have made our history glorious. They remind us of the illimitable vastness of opportunity to him who is willing to serve; they preserve in pictorial form the history and traditions of a great though modest commonwealth; they inspire us with a laudable desire to so live our lives that posterity may say of us, that we also “have done the State some service.”

And so we come today to speak of one who writ his name large in the annals of the State's history; of one who in every walk of life into which he directed his steps, made the observer take note that a man had passed.

In our childhood days we used to stand against the wall to be measured of our stature, and in many an old homestead in

the State upon the crumbling walls are marked the records of the children's annual growth. It was before the days of automatic devices that, for a penny in the slot, will weigh and measure you, and prophesy your future fortune.

It is my purpose briefly to stand General William Ruffin Cox against the wall of history, and measure, as best I may, his stature as a soldier, as a statesman, and as a civilian.

It is not necessary or desirable to make this address a mere biographical sketch of our distinguished subject; a skillfuller and abler hand than mine has done this. Captain S. A. Ashe has penned the inspiring story and preserved it in permanent form, in volume one, of the “Biographical History of North Carolina.”

I have drawn largely upon this incomparable sketch for my facts in the preparation of this paper, and here and now wish to make to him due acknowledgment.

Born of highly honorable parentage, on March 11, 1832, General Cox was a descendant of the Cavalier rather than the Puritan. He was orphaned by his father's death when only four years old, and, upon his cultured and gifted mother, fell the burden of his early training. There was something in the serene and stately bearing of the man—in his perfect poise—in the careful modulation of his rich masculine voice—and in his grave and dignified courtesy, that, to the end, reflected the early impression of that magical mother love and training.

He came to the Bar in Tennessee in 1852, and resided at Nashville until 1857, as the junior partner of John G. Ferguson, a lawyer of distinction, and a kinsman of Hon. G. S. Ferguson, some time Judge of our Superior Court.

In 1857, he married Miss Penelope B. Battle, sister of the wife of the late Dr. Kemp P. Battle, of Chapel Hill, and came to North Carolina to live.

The mutterings of the coming storm were already audible. The political atmosphere was becoming more and more tense

and surcharged with feeling and, as the crisis approached, the question of States’ Rights was being discussed, not always calmly, alike by the learned and the unlearned. General Cox, who had, in 1859, removed to Raleigh, was an ardent believer in the doctrine of States’ Rights as expounded by Mr. Jefferson Davis, and, believing that war was inevitable, in company with several others, he equipped a battery. So began his highly honorable military career.

Almost immediately upon the outbreak of hostilities, he was appointed by Governor Ellis, Major of the Second North Carolina Troops, and entered upon actual service.

Time and space will permit us to do no more than touch upon the “high lights” of one of the most unique military careers in the Great War Between the States. General Cox and the Second North Carolina Troops were to win imperishable renown before the curtain fell upon the lurid drama. At Mechanicsville, on June 26, 1862, and lasting through seven days of shot and shell, he and his regiment received their first baptism of fire, and helped to hurl back McClellan's incomparable army and “to drive it, defeated, disorganized and cowering, under the protection of the Federal Gun Boats at Harrison's Landing.” After that he was a veteran, cool and intrepid.

At Malvern Hill, he was severely wounded and could not rejoin his regiment until after the battle of South Mountain. Followed in rapid sequence, Sharpsburg, bloody and desperate; victory at Fredericksburg, and then Chancellorsville, with its unutterable tragedy. Here we pause to quote from Captain Ashe's spirited account:

“At Chancellorsville, on Friday evening, Colonel Cox moved up and drove in Hooker's outposts, the regiment lying that night so near to the enemy that all orders were given in whispers; and the next morning Cox's regiment was one of the sixteen North Carolina regiments that Jackson led in his memorable march across Hooker's front, reaching the rear of Siegel's troops

about sunset. The men were in line, stooping like athletes, when Ramseur, their brigade commander, ordered ‘Forward at once,’ and Cox, leading his regiment, drove the enemy from their works; but his troops were subjected to a terrific enfilading artillery fire at only 200 yards distance, and in fifteen minutes he lost 300 of the 400 men he had carried in with him. The gallant colonel himself received five wounds, but continued on the field until exhausted. Of him the lamented Ramseur said in his report: ‘The manly and chivalrous Cox of the Second North Carolina, the accomplished gentleman, splendid soldier and warm friend, who, though wounded five times, remained with his regiment until exhausted. In common with the entire command, I regret his temporary absence from the field, where he loves to be.’ The brigade received, through General Lee, a message of praise from the dying lips of General Jackson.”

Spottsylvania with its record of glorious achievement, followed and the part played by the brigade, of which General Cox's regiment was a part, evoked from General Lee words of personal thanks for their gallant conduct, and brought to General Cox his Commission as Brigadier General. “After that time,” to quote again from Captain Ashe's inspiring account, “General Cox led the brigade that, under Anderson and Ramseur, had been so distinguished in all the fields of blood and carnage, in which the Army of Northern Virginia had won such glory.”

It was to fall to the lot of General Cox's brigade, under his leadership, to further immortalize itself. He led the brigade to Silver Springs within a few miles and in sight of the White House at Washington. This was the nearest point to the seat of the Federal Government which the Confederate Troops at any time approached. Thence he was recalled to General Lee's aid at Petersburg to share there with his brigade all the hardships and cruel privations of that memorable siege. I quote again from Captain Ashe's vivid account:

“Once more it was General Cox's fortune to draw from General Lee an expression of high commendation. It was during

the retreat from Petersburg, at Sailor's Creek, just after Lee's retiring army had been overwhelmed and the utmost confusion prevailed, the soldiers straggling along hopelessly, many leaving deliberately for their homes, and the demoralization increasing every moment, while the enemy, in overwhelming numbers, pressed on so closely that a stand had to be made to save the trains, upon which all depended. Lee sent his staff to rally the stragglers, but they met with indifferent success. All seemed mixed in hopeless, inextricable confusion, and the greatest disorder prevailed, when presently an orderly column approached, a small but entire brigade, its commander at its head, and colors flying, and it filed promptly and with precision into its appointed position. A smile of momentary joy passed over the distressed features of General Lee, as he called out to an aide, “What troops are those?” “Cox's North Carolina Brigade,” was the reply. Taking off his hat and bowing his head with courtesy and kindly feeling, General Lee exclaimed, “God bless gallant old North Carolina!” This occasion has been graphically described in a public address made by Governor Vance after the war.

Stand General Cox, therefore, against the wall of history and measure his stature as a soldier. Assaying him by his accomplishments and what he attained, we know it may be said of him that no more gallant soldier than this distinguished North Carolinian went forth from the State to fight its battles. In his body he bore the marks of eleven wounds received during those bloody four years.

Was his career as a Statesman any less distinguished? Let us examine the record in this respect.

With the war ended and the return of the disbanded soldiers to civil life after four years of military duty, the demand for high and disinterested service was tragically great. War is the very culmination of lawlessness; it is the resort of men to primitive and lawless methods of arbitrament, and law ends where

war begins. The lawlessness, which is the culmination of and is typified in war, affects, to the very core, the citizenship that is engaged. In proof of this, you have but to observe the wave of crime and rapine that has swept over this country in the two years and a half since the armistice was signed. We have stood amazed and horrified at the recital of crimes perpetrated even in our very midst, and no hamlet is so quiet or so well ordered that it has not its chapter of bloodshed and outrage. Human life becomes so cheap, and property rights of so small account, when a million men are fighting breast to breast at each other's throats, that the lust to kill cannot be soothed into quiet by the mere signing of an armistice or treaty.

So, when General Cox, who at the time of the surrender had become an unique and dominant figure in the Army of Northern Virginia, surrendered his sword and laid aside the habiliments of war, he came home to take up a task vaster in its significance and ultimate fruitage than were his duties as a soldier. He was to throw his great prestige and strong personality into the labor of re-building a chaotic and bankrupt State. He was to co-operate with and aid other leaders in directing the energies and passions, engendered by war, into channels that would not only render them innocuous, but positively helpful. Here was a mighty dynamic force that was full of dangerous menace; but, if it could be controlled and directed, it would become potential for the accomplishment of great good to the State.

Mr. President, as proud as we are and should ever be of the glorious record of the North Carolina Troops in the Confederate service, I declare to you that, in my judgment, the brightest page in our great State's history is that written by leaders and led in those years following hard upon the war. Even with a half century between us and those fateful years when our very civilization was gasping for its life, and our social and political institutions were debauched and chaotic, we are too close to the tragic events to understand their significance, or to rightly appreciate the mighty part played by those great souled

men. More years yet are needed to give us the proper perspective of the great and sublime devotion of those men who took upon themselves the high and holy duty of re-building the wearied, discouraged and broken State.

Among those men there immediately moved out to the front the martial figure of the man of whom we speak.

Coming back to Raleigh, he began the practice of law. A solicitor of the metropolitan district was to be elected, and General Cox had the courage, although the district was overwhelmingly Republican, to announce himself a candidate for the Democratic nomination. It was the first formal notice given by the returning remnant of Lee's Army that it would not suffer things in North Carolina to go by default. It rang out the brave challenge that “The old guard can die but it cannot surrender.” The Republican organization in the district approached him with the proposition that, if he would run as an Independent, the organization would endorse him. He refused its blandishments and ran on the ticket as a Democrat, and, when the election returns were in, to the joy and surprise of his friends, he was found to have been elected by a narrow margin.

This office, so full of possibilities for good when administered by a high-minded, clean man, and so potent for evil if maladministered, he filled with high credit to himself and with entire satisfaction to the District, for six years. His capabilities being thus successfully subjected to the acid test, his further promotion came rapidly, but brought with it increased responsibility and gruelling labor; for

“The heights by great men reached and kept,Were not attained by sudden flight;But they, while their companions slept,Were toiling upward in the night.”He had become Chairman of the State Democratic Executive Committee, and, when his term as Solicitor ended, he refused

a renomination in order to devote all his powers and energy to overthrowing the Republican machine in the State. In 1874, while he was Chairman, the State was redeemed by a Democratic majority of about 13,000. In 1875, when the popular vote was being had upon the State Constitutional Convention, there went out from his office, as Chairman of the State Executive Committee, that trenchant and historic telegram to the Democratic Headquarters in Robeson: “As you love your State, hold Robeson.” Doubtless, as a result of this patriotic appeal, Robeson was held and the State was saved. I count it one of my high privileges to have heard General Cox, who was as modest about his own exploits as a woman, personally relate the stirring narrative.

In 1876, still retaining the Chairmanship of the State Executive Committee, he conducted the great Vance-Settle campaign, resulting in the election of Governor Vance, after the most dramatic contest ever waged in the State.

In 1877, he was appointed Judge of the Superior Court for the Sixth District, and discharged most acceptably and ably the duties of this high office until he resigned to seek and to canvass for the nomination for Congress. Having won the nomination, he was triumphantly elected, serving in the United States Congress for six years.

In 1892, General Cox was elected Secretary of the Senate of the United States, a position of great honor and trust. To the discharge of the duties of this office, he brought all his great natural ability and fine culture. After the expiration of his term of office as Secretary of the Senate, he held no other political office.

If the measure of a man's powers be the success he attains in all his undertakings, surely, measuring General's Cox's civil life upon the wall of history, he was a statesman. In his office as Solicitor, he had been clean, strong, capable and absolutely unafraid. He came to the office in troublous times, and he met

its duties in the calm, commanding way that banishes difficulties almost without a conflict. His administration of the usually thankless office of Chairman of the State Democratic Executive Committee was so brilliant and so successful that it has passed into the Party's most glorious history. He came to the Bench while the Code System was yet in its experimental stage in the State, and his urbanity, his dignity, his great common sense, his broad reading and his innate courtesy made him an ideal nisi prius Judge.

He went into the Congress of United States, and became the friend and adviser of the President, and the trusted counsellor of the great party leaders. He passed into the office of the Secretary of the Senate, and was on terms of intimacy with those great souls who held manhood cheap that was not bottomed fast on rock-ribbed honesty. He left that office, where yet the older generation speak of him as the “Chivalric Cox,” and came to his home and farm on Tar River, in Edgecombe County, to live the simple, quiet life of the Southern planter.

Great warrior, distinguished and successful statesman, what will he do amid the homely surroundings of the North Carolina cotton plantation with the proverbial “nigger and his mule.”

To the direction of this great farm, he brought the order and system of the soldier and the vision and courage of the statesman. He introduced blooded stock and modern machinery. He raised the finest sheep and the best pigs in the county. His yield per acre was a little better than any of his neighbors. If rain or drouth, flood or storm came, he was always calm and imperturbable, and no man ever heard him utter a word of complaint. In his well selected and large library, he read not only history and biography, but chemistry, and books on food plant, and volumes on agricultural science. Your speaker has more than once been down to the country home at Penelo and found the General with books on the floors and tables all around him, running down the subjects of scientific fertilization.

He was a successful farmer. He entered no field of activity in which he did not succeed, and it was difficult, at the end of his distinguished life to say in which field were his most successful achievements.

Three years after the death of his first wife, who died in 1880, General Cox married Miss Fannie Augusta Lyman, daughter of the Right Reverend Theodore B. Lyman, Bishop of North Carolina. After two years of wedded life, she died, leaving her surviving two sons, Col. Albert L. Cox, distinguished soldier, judge and lawyer of this city, and Captain Francis Cox, now a candidate for Holy Orders.

In June, 1905, General Cox was married to the charming and gracious Mrs. Herbert A. Claiborne, daughter of Col. Henry C. Cabell, of Richmond, Va., who graces this occasion with her presence today.

I have tried more than once to summarize, or catalogue those particular or accentuated virtues or characteristics which marked General Cox as truly great. He was a man of singularly handsome person, tall, erect and soldierly in bearing, with high-bred, classical features. His manner was one of utmost composure and quiet certitude. His imperturbability could not be shaken, and he looked the part of the man, to whom, in great crises, other men would naturally turn for leadership. His dominant characteristics I would catalogue as follows:

He was physically and morally as brave a man as I ever knew, and this mental condition was that which made him so singularly effective when emergency arose. His courage was so unconscious and so ingrained, that I have frequently thought it was the cause, at least in larger part, of his serene composure and quiet bearing.

He was inherently a just man. Although, by training and habit of mind, he was a rigid disciplinarian, yet there was nothing about him of the martinet, and, in determining, as he was

frequently called upon to do, the small controversies that are inevitable in the conduct of a large farm, whether between landlord and tenant, or cropper and cropper, he was as impersonal as he had been when he was presiding as a judge.

He was rigidly honest, and, by that term, I do not mean simply that he discharged his legal obligations; he did more than that. He dared to follow truth to its ultimate end, and the popularity or unpopularity of the conclusions he reached did not in the slightest way affect him.

He was a clean man. He thought and lived cleanly. His mind was occupied with clean thoughts, and he nourished it upon good books and wholesome literature. He never told an anecdote of questionable character, or uttered an obscene or profane word.

He was an intensely patriotic man, and, with a devotion as ardent as a lover for his mistress, he loved North Carolina—her heritage and her history—her traditions and her customs—her people and her institutions. In the evening of his long and eventful life, as he sat in the shadow of the majestic oaks that embowered his home, he thought much upon the problems that were arising and presenting themselves for solution, and he believed, with all the strength of his soul, in the ability of the State to wisely solve them and to attain her future great destiny.

He was one of the most evenly courteous men in his manner and bearing that I ever saw. A partrician by birth and association, he was yet as gravely courteous and as formally polite to the humblest mule driver on his farm as he was to the greatest of the historic figures amid whom he had lived his eventful life. Calm, strong, urbane and dignified, he went through life, and the world knew him as one born to command.

In a career, crowned with high achievements, both in military and civil life, there was nothing adventitious or accidental. There was in him a definite nobility of soul and mind and person which marked him as one of nature's noblemen. His fearlessness

and heroic courage, his perfect sense of justice, his unblemished integrity, his intense and flaming patriotism, his fund of practical common sense, his perfect poise and unruffled composure; his manly bearing and unfailing courtesy—added to his singularly handsome face and person and to his splendid physique, combined to make him one of “The Choice and Master Spirits of this Age.”

Mr. President, in behalf of his bereaved and gracious widow, I have the honor to formally present to the North Carolina Hall of History this excellent portrait of the man, in honoring whom we honor ourselves. For her, I request that it may be hung on the walls of this building to the end that future generations, looking upon his strong, composed and handsome features, may seek to emulate his high example of service and devotion.

Acceptance of the Portrait of GeneralWilliam R. Cox

BY CHIEF JUSTICE HON. WALTER CLARK, SUPREME COURT OF

NORTH CAROLINA.

Nothing could be added to the eloquent and just appreciation of the military and civil services of General William R. Cox which has just been delivered by Mr. Spruill, without marring its beauty.

It was said by a keen analyst of character that while it was not claimed that Marshal Ney was the ablest and most successful Marshal of Napoleon, that there was none of the marshals who more accurately personified the typical French soldier than he who embodied in his career and his services the ideal characteristics of the French soldier—his courage, his endurance of hardship, his sense of duty and fidelity.

Of the more than 125,000 soldiers whom North Carolina sent to the field in the great struggle of 1861-65, there is none who more fully and faithfully personified the ideal of the North Carolina soldier than General Cox.

On 20 May, 1861—60 years ago—120 representatives, bearing the commission of North Carolina to decide her action in a great crisis, met in the southern end of the Capitol. On that day they expressed by a unanimous vote the will of the people of this State that North Carolina should repeal the ordinance enacted at Fayetteville in November, 1789, by which she had become a member of the Federal Union, and should assert her right to become again a free, independent and sovereign State. When the vote was announced by the venerable President, Hon. Weldon N. Edwards, of Warren, Governor Ellis’ secretary, Major Graham Daves, threw open a window on the west side

of the House of Representatives and announced the historic act to a young officer commanding a battery of artillery just below. That officer, then Captain of artillery, later became known to fame as Major General Stephen D. Ramseur, and a salvo of artillery made known the result to a waiting people.

Quickly appropriate measures followed and from all that now constitutes the one hundred counties of North Carolina, men left their homes and fire-sides and crowded to the perilous edge of battle. First and last there came 127,500 soldiers from a State with less than 115,000 voters. The carpenter on the housetop came down but it was to gather up his scanty belongings and leave for the post of duty; the blacksmith left his bellows and the still glowing iron; the bare-foot boy on the mountain-side, or by the rivers in the east, left his plow in the furrow. Men of every rank and station of society hastened to the call of the State. When the four years were over they came back but not all of them. More than 42,000 came not home again. This is not the time and place to recall what they did and dared, but as a typical soldier, we may take the gallant man whose portrait is presented to us this day and which North Carolina is proud to hang upon the walls of her museum of history.

Raising a company at the outset of the war, he rose to the command of a brigade. Seven times wounded, he returned promptly to the post of duty when his physical condition permitted. At Chancellorsville, struck with five bullets, he remained at the head of his column until victory was won. In the farthest advance made by the Southern troops upon Washington city, he occupied the nearest post reached by the Confederates, in sight of the dome of the Capitol. On the retreat from Petersburg, the funeral march of the Confederacy, at Sailor's Creek, when his diminished command passed with martial step and in compact column, buoyant and bold, General Lee, standing by the roadside, asked what command it was and when told that it was Cox's North Carolina Brigade, he responded, “God bless North Carolina.” And at the final scene when the silver throated cannon

sobbed themselves into silence amid the hills of Appomattox, it was Cox's Brigade, of Grimes’ Division, and under his leadership that made the last charge of that immortal Army of Northern Virginia. The State has long since erected a marble shaft to the memory of that historic event and it is appropriate today that we should unveil this portrait to the leader of that charge, a typical North Carolina Confederate soldier—General William R. Cox.

In her long history from the hour when the keels of Amadas and Barlow grated upon her storm-bound coast, down to this fleeting moment, the noblest and greatest period of our story has been the devotion and courage of the soldiers and people of North Carolina, during those four eventful years from 1861-65, the memory of which can never be forgotten. From the roll of the surf on the east to the Great Smokies, whose peaks stand as the sentinels of the ages along her western border, the State was stirred and moved as never before or since.

The greatest figure of that time, of which the subject of this portrait is a type, was “the Confederate soldier,” of whom it may be said without eulogy, but in simple truth, that as long as the breezes blow, while the grasses grow, while the rivers run, his record can be summed up in eternal fame in this sentence,

“He did his duty.”

On the part of the State, we accept this portrait, which has been so handsomely presented by the donor and by the orator of this occasion.