The Freedman. From the Statuette by J. Q. A. Ward.

REPORTOF THE SERVICES RENDERED BY THE FREED PEOPLETO THEUnited States Army, in North Carolina,IN THE SPRING OF 1862, AFTER THE BATTLE OF NEWBERNBy VINCENT COLYERSuperintendent of the Poor under General Burnside. “So that they cause the cry of the poor to come unto Him, and He heareth the cry of the afflicted. When He giveth quietness who then can make trouble? and when He hideth His face, who then can behold Him? whether it be done against a nation or a man only.”—Job xxxiv: 28, 29. New York:Published by VINCENT COLYER, No. 105 Bleecker Street.1864.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1864, by Vincent Colyer, In the Clerk's Office of the United States District Court, for the Southern District of the State of New York.

The Services of the Freed-People TO THE UNION ARMY IN NORTH CAROLINA.I commenced my work with the freed people of color, in North Carolina, at Roanoke Island, soon after the battle of the 8th of February, 1862, which resulted so gloriously for our country.

A party of fifteen or twenty of these loyal blacks, men, women and children, arrived on a “Dingy” in front of the General's Head Quarters, where my tent was located. They came from up the Chowan River, and as they were passing they had been shot at by their rebel masters from the banks of the river, but escaped uninjured.

They were a happy party, rejoicing at their escape from slavery and danger, and at the hearty welcome which was at once extended to them, by the officers and men of the New England regiments, which chiefly made up the corps under Gen. Burnside's command.

It rained hard that night, and shelter being rather scarce on that Island, I gave up my tent to the women and children, and found quarters for myself with a neighbor.

The calm trustful faith with which these poor people came over from the enemy, to our shores; the unbounded joy which they manifested when they found themselves within our lines, and Free; made an impression on my mind not easily effaced. Many of the officers, notwithstanding the rain, gathered around the tent to hear them sing the hymn, “The precious Lamb, Christ Jesus, was crucified for me.”

After the battle of Newbern, when my work in the hospitals

was over, General Burnside placed all the freed people, and also the poor whites, under my charge, issuing the following order:

Head Quarters, Department of North Carolina.

Newbern, March 30, 1862.

Mr. Vincent Colyer is hereby appointed Superintendent of the Poor, and will be obeyed and respected accordingly.

By command of Major General BURNSIDE: Lewis Richmond, Ass't Adj't General.

NEGROES NOT A BURTHEN.My first order from General Burnside under this appointment, was to employ as many negro men as I could get, up to the number of five thousand; to offer them eight dollars a month, one ration and clothes, to work on the building of forts. This Order remained standing on my books up to the day I left the Department with the General, July 6th, without our ever being able to fill it. At the time I left, there were not over twenty-five hundred able-bodied men within our lines: so that it will be readily understood why the negroes were never a burden on our hands. The truth was, we never could get enough of them: and although for a little while, there were a few more at Roanoke Island than were wanted there after the Fort was completed, they were brought to Newbern as soon as it was known.

| At Newbern and vicinity, | 7,500 |

| At Roanoke Island and parts adjacent, | 1,000 |

| At Washington, Hatteras, Carolina and Beaufort, | 1,500 |

In all 10,000, of whom 2,500 were men, 7,500 women and children.

Placing the Stockade in Building the Forts.THE WORK THEY DID.

In the four months that I had charge of them, the men built three first-class earth-work forts: Fort Totten, at Newbern—a large work; Fort Burnside, on the upper end of Roanoke Island; and Fort—, at Washington, N. C. These three forts were our chief reliance for defence against the rebels, in case of an attack; and have since been successfully used for that purpose by our forces under Major-Generals Foster and Peck, in the two attempts which have been made by the rebels to retake Newbern.

The negroes loaded and discharged cargoes, for about three hundred vessels, served regularly as crews on about twenty steamers, and acted as permanent gangs of laborers in all the Quartermasters’, Commissary and Ordinance Offices of the Department. A number of the men were good carpenters, blacksmiths, coopers, &c., and did effective work in their trades at bridge-building, ship-joining, &c. A number of the wooden cots in the hospital, and considerable of the blacksmith and wheelwright work was done by them. One shop in Hancock Street, kept by a freedman, of which the engraving on another page gives a fair picture, usually presented a busy scene of cheerful industry. The large rail road bridge across the Trent was built chiefly by them, as were also the bridges across Batchelor's and other Creeks, and the docks at Roanoke Island and elsewhere. Upwards of fifty volunteers of the best and most courageous, were kept constantly employed on the perilous but important duty of spies, scouts, and guides. In this work they were invaluable and almost indispensable. They frequently went from thirty to three hundred miles within the enemy's lines; visiting his principal camps and most important posts, and bringing us back important and reliable information. They visited within the rebel lines Kingston, Goldsboro, Trenton, Onslow, Swansboro, Tarboro and points on the Roanoke River: often on these errands barely escaping with their lives. They were pursued on several occasions by blood-hounds, two or three of them were taken prisoners; one of these was known to have been shot, and the fate of the others was not ascertained. The pay they received for this work was small but satisfactory. They

seemed to think their lives were well spent, if necessary, in giving rest, security and success to the Union troops, whom they regarded as their deliverers. They usually knelt in solemn prayer before they left, and on their return from these hazardous errands, as they considered the work as a religious duty.

THEIR SERVICES AS SPIES.One morning, in the beginning of this pioneer duty, the provost Guard in front of my door told me that two negro spies sent by the rebels into our lines, had been caught by our pickets. I had sent two men to Kingston, with instructions that they should report only to me; on their return they were examined by the pickets and officers of the outposts, who, ignorant of our doings in this way, and completely mystified by the negroes, sent the two men under strong guard to General Foster. The General himself, not having been told by General Burnside of the authority which had been given to me, of sending out men on these expeditions, was going by my door at the time the guard were passing with these men. For convenience he brought them into my office; when, to my astonishment I found that the noted negro prisoners, of whom I had heard early in the morning were my two men. So faithful were they to my order, that though subjected to suspicion and indignity all the morning, from their own friends, they had not betrayed their trust.

By the following special Order, the care of this branch of the service, in the neighborhood of Newbern, was, after the above affair, placed exclusively in my hands, and I have graphic details recorded of their journeys:

Headquarters’ Division, Dep. N. C., April 24th, 1862.

The Colonels commanding the Brigades of the Divisions, will instruct the Commander of their out-posts, to respect the passes given to negroes by Mr. Vincent Colyer, to pass out of our lines, and the Commanders of the out-posts will be further instructed, that any man coming to our lines, and asking for Mr. Colyer, must be immediately sent to him, without molestation or examination of any kind whatever; and the guard

The Freedmen's Blacksmith and Wheelwright Shop. (See page 9.)sent in must be particularly instructed to hold no conversation whatever with the person.

By order of Brig.-General Foster,

Southard Hoffman,

Assist. Adj't Gen'l.

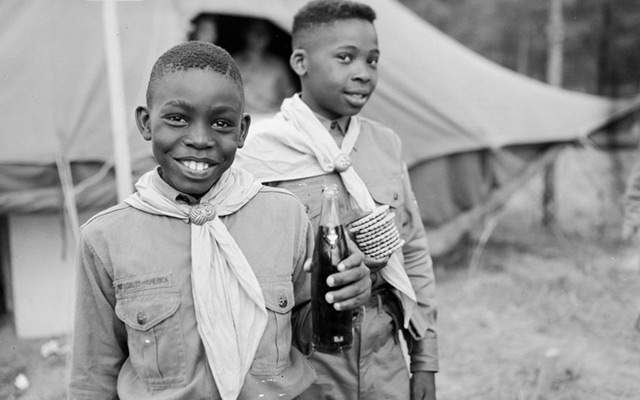

The name of one of these two faithful men who thus opened the way for the carrying on of this important service—was Furney Bryant. At that time now two years ago, he did not know a letter of the alphaabet, and he came within our lines dressed in the rags of the plantation. He attended my schools and after I left Newbern, on the formation of the 1st North Carolina Colored Reg't, he enlisted, and with his regiment was or dered for duty with General Gilmore off Charleston; where his gallantry and intelligence caused him to receive the appointment of 1st Sergeant, and a leave of absence of thirty days. On his way home to Newbern he came to New York city and called on me. The contrast in his personal appearance, in his new suit of Army blue, was not more remakable than the following letter received from him since his return to duty, proves his growth in the knowledge of letters to be. Let no one say that freedom is not better than slavery, with such examples before them.

Furney Bryant, the RefugeeIn company with three other soldiers of his regiment, he arrived in Newbern in time to participate in the defence of that place against the recent desperate attack of the rebels

in February, 1864. The engraving represents him, in company with Corporal Owen Jones heroically defending his native town, and the government which had set him free, against the secessionists. (See page 17.)

SERGEANT BRYANT'S LETTER.Jacksonville Florida, March 23, 1864.

My Dear friend, Mr. Colyer,

In a few lines, I will inform you that I am in good health. I am happy in having the pleasure of writing to you while studying over all the care and affection which you have shown towards the colored people. I do say, and truly believe, that you will have your reward in Heaven.

I hope that God will prosper you in all your undertakings and that you may forever find pleasure in your duties, looking unto God.

I trust to meet you and your kind brother-in-law, Mr. Geo. Hancock, in this world, but if I should not, then I hope to meet you in Heaven.

It was my desire to have called upon you a gain before I left New York, but the steamer left so hurriedly we could not. Sergeant Lewis Bryant, Corporal Owen Jones, William White and John Hatch send their love. Bringing my letter to a close, in reading over all I have written I can only say, Amen

Sergeant Furney Bryant, 1st North Carolina Colored Troops.Sergeant, Furney Bryant.

UNION SCOUTS.—CHARLEY.A negro boy, Charley, made three journeys to Kingston, at that time the head-quarters of the enemy. The distance was

forty-five miles, thirty within the enemy's lines. On the first visit, he brought us information that the enemy's camp and a large portion of his forces were removed some miles and across a river. Upon the closest questioning by the General, no discrepancy or contradiction could be found in his statements. On his third journey, in company with another boy, he was about five miles above Kingston, when he was suddenly overtaken by a rebel on horseback, with a pack of bloodhounds by his side, scouring the woods, and the dogs evidently on their trail. The negroes waited cautiously in a thick copse of wood, and as the man rode round the thicket, before the dogs came up, they fired their revolvers at him. They missed the man but shot his horse. In a minute the dogs came in, when they turned quickly and shot two of the dogs. The man hearing the repeated firing and the howling of his dogs, and unable to tell the character or numbers of his enemies, quickly ran off. The boys also ran in the opposite direction with equal, or perhaps, superior alertness, for they had farther to go to reach home,—some thirty-six miles to our nearest pickets. They continued to run and rest at intervals, until they were within twelve miles of our lines, when they heard the bark of more dogs, and the sound of men's voices urged them on. Knowing that the dogs were after them, and realizing their danger, they ran very fast, and taking to the water in the swamps, whenever possible, for several miles they baffled the scent of the dogs, and kept at a distance ahead of them. At last, seeing that they were nearly upon them, and the men a long distance behind, they quickly got ready their revolvers, and awaited the attack of the dogs. Placing their backs against trees, they took cool and deliberate aim, and wounded three of them, and sent them howling back to their owners. The men in pursuit, hearing the firing and howling of the dogs, set up a shout and hurried forward, until they came near the place where the fight had occurred, when they advanced, it is supposed, more cautiously, fearing an ambush. The negro boys came home as fast as they could run, throwing off coats, pants, caps, and everything but their shirts, drawers, and revolvers, finally reaching our lines in safety, completely exhausted.

CHARACTER OF MEN EMPLOYED AS SCOUTS.

In order that you may have a correct idea of the character of the men from among whom these spies were selected, let me give you the brief personal history of one of them, as I wrote it down from his own lips, previous to employing him on one of these visits. You will then be able to judge more readily whether they would be likely to have the enterprise and necessary ability to undertake such dangerous duties.

I will preface his story by saying that he was a tall, intelligent looking, well formed negro, of a singularly modest, refined and ingenuous look. His long incarceration in the woods, and non-communion with his fellows, had given him a meditative air and manner that was peculiar. He told his story without any apparent idea that it was in the least remarkable or uncommon, or with a thought of being a hero, yet with a full consciousness of the injustice and wrong to which he had in common with his race been subjected to while in slavery.

His dignity, earnestness, and uncomplaining resignation of manner should be known to have the story rightly appreciated.

HISTORY OF A SCOUT.—WM. KINNEGY.My name is William Kinnegy; I belonged to * * who lived on * * * in Jones County, North Carolina, where I was born, in what year, I could never ascertain. After * * *’s death, his son * * * drew lots and obtained me and left me to his * * *'s son * * * This * * * sent me to Richmond to be sold, about six years ago. I was taken to jail, and after remaining there about two months, I was brought out and placed in the slave pen. They made us (there was a number from different parts of the country, all strangers to me,) strip stark naked; the women in one part of the room, the men in another; a rough cotton screen separating the two sexes. We were stood off at a short distance from our purchasers, and our physical condition fully considered and remarked upon, holding up our hands, turning round, and then we were sold accordingly. They did not call

Sergeant Bryant and Corporal Jones Defending Newbern, February, 1864.

us “people,” but “stock.” ’ I had been used in North Carolina to the title, “droves of people,” but there in Richmond, they called us “droves of stock,” “heads of stock,” &c. After knocking about between different purchasers, I was traded off to go South. * * * and * * *, traders, bought me, and afterwards sold me to a man named * * * to go South in Alabama. They took me out of Richmond jail, and in company with one hundred others, men, women and children, they put me on the train on the Welden and Goldsborough Railroad. We were to go to Wilmington, and from there by water to Alabama. When the train had passed Goldsborough, and was below Strickland's depot, on the Goldsborough and Wilmington Railroad, it was night. Knowing that I was then as near to the residence of my wife and children, as I ever probably should be, I made an excuse to look out of the door, and watching my chance, while the train was in full motion, passing through a wood, I jumped off. I was three days and four nights in the woods before I got anything to eat. Bruised badly, and suffering from the strain of jumping off the train, being compelled to avoid every habitation, and in the woods and swamps I had a hard time of it. At the close of the fourth night, a colored man, a slave, gave me some food. After a while I reached my home and met my wife. It was still dark, and having had a word of good cheer from her, and kisses from my three children, I took a little food and returned to the woods, five miles away.

I have a son twenty-three years old, whom you know as * * *, he works on the fort for the United States Government; and a daughter twenty-three years old, who was sold to a planter, I believe in Alabama; and four small children under the age of twelve years, two of whom have been born since I lived in the woods. These six children were all by the same wife * * *. I staid in the woods in a close jungle, so thick that you could not penetrate it, except with the axe; and from that time to this, (it was February 12th, 1857, mid-winter, when I jumped off the train) now over five years, I have lived in that woods. I dared not permit myself to be seen by a white man for months, and then only by one or two of the very poorest, who traded with me in small things. I slept

under the boughs and on a bed of pine blooms for a month or two (mid-winter and plenty of rain) until spring, when I began to build me a hut. I cut down small trees, and from an old fence got some boards, and soon built a place large enough to sleep in. I had to get a saw, so as not to make a noise; the sound of an axe would be heard a much greater distance. There were a great many cattle and swine in the glades among the reeds on which they feed in the fall. I have seen three and four hundred in a drove. They get so wild and skittish that the owners rarely keep any account of them. The poor people about, frequently kill them, and the owners seem not to be aware of it, or do not care for it. They are generally lean and thin cattle while left in this way. I killed one occasionally, and by trading a pig which I had killed and dressed, and leaving it in a place designated, a poor white man with whom I accidentally became acquainted; by previous arrangement brought a gun and left it in the same place. I took the gun and he took the pig, of course without meeting each other. Afterwards I exchanged other things; the hide of a cow, &c., for shot and powder. If I had received them from him in person, or he had been found out, his punishment would have been very severe; but I saw him but rarely, as my acquaintance was too dangerous a thing for him. Once I was hunted out by bloodhounds. One Jim McDaniel kept a pack of these dogs, and they were put on my track.* There were eight dogs, and they were upon me before I had time to prepare. With an old scythe which I had made into a cutlass, I killed two and crippled another, but I was forced to fly to the middle of the swamp to get clear of them, wading up to my middle in water and mud. After some days I returned to my hut, and found that my pursuers had robbed me of everything, and nearly destroyed the hut. This would not be considered worth much to most people under ordinary circumstances, but it was a great loss to me, and besides, compelled me to change my hiding place. As I had been from youth up always in delicate health (was “sickly,” as they called me,) and was sold to the traders by my owner * * * very low, and

*This man and his dogs were captured by Col. Mix's cavalry a short time since, and he is now in Newbern jail.—V. Colyer.he had got his money, they did not make that careful search for me they would otherwise have done. My wife's owner offered $400 for me, but my master thought he could get more than that for me in Richmond, and so I was sent there. The Alabama planter, who bought me, paid $700 for me, I was told. I never dared to stay at my wife's cabin more than a few minutes at a time, although it was always night when I visited her.

Wm. Kinnegy Returning to the Union Army with his Family, from Whom he had been Separated by Slavery for Five Years.She has been as faithful a wife to me as woman could be, and though she has had two children since I have lived in the woods, their resemblance to the others is so striking, that their master troubled my wife very much to get her to betray my where-abouts.

As soon as possible after the United States army took Newbern, I came within the Union lines. I have worked a month for you on the fort, have eight dollars, wages received there, in my pocket, and now hearing that my wife's owner has run away, and she and the children are up in the country alone, I have come to you for a pass to go and bring them down.”

I listened to his simple story, and then asked him if he would be willing, while after his wife, to go a little further, up to Kingston and thereabout, and take a good look at the rebel encampments, make a careful note on his memory of their number and situation, inquire of the negroes in their cabins all about the enemy, and bring this information for us, with his wife and children on his return. I told him I would pay him handsomely if he brought us information of value. He said he would gladly, he knew every inch of the road. I gave him rations for three days, some small change in silver, and a pass. Two weeks after this the tall form of this negro stood before me, he had returned with his wife and four children. He said, “Sir, this is the first time in five years I have dared to stand before a white man, and call my wife and children my own.”

He brought us very valuable information.

REFUGEES FROM ALABAMA.Two negroes came from the Northern part of Alabama where they had been in the woods for over a year. They were three months in making their way through the woods and bye-paths, avoiding white men all the way, from Alabama to Newbern a distance of seven hundred and fifty miles.

They arrived in June.

ALSO FROM SOUTH CAROLINA.Two other negroes came from South Carolina, they were nearly six weeks on their way; these two had escaped to the woods on the fall of Fort Sumpter, and like the two from Alabama, were well acquinted with the cause of the war, that is, the cause as all the negroes understand it, viz: slavery.

FEARS OF A FLANK MOVEMENT DISMISSED.Two free negroes from Onslow County had lived in the woods for more than a year, to escape being drafted to work on the enemy's fortifications. They were very intelligent and devoted to our cause. It was reported that the rebels were advancing in force from that direction, threatening our rail road communication with Beaufort. Gen. Foster wanted two scouts to search the neighborhood thoroughly, and report if they met any of the enemy's troops, their number, location, &c. I sent these two free blacks, and after four days absence they returned, having been over a circuit of forty-five miles,

The Freedmen as Union Scouts.part of the time in a heavy storm, through woods and swamps, in negro cabins, &c., and relieved the minds of the Commander by their full and satisfactory report. Both these men were laid up with the measles for a week, and came near dying from their exposure.

HINTS TO SCOUTS IN FUTURE SERVICE.One man from the neighborhood of Tarboro led a scouting party to that place and got the information we wanted, and returning was discovered by the rebels, and chased by dogs. He escaped by bathing the feet of his party in turpentine, which is said to effectually destroy the scent, and prevent the dogs from following the trail.

AN ESCAPE WITHOUT DISCOURAGMENT.Two scouts, after trying in vain to pass the enemy's pickets above Newbern, attempted to steal up the Neuse river at early dawn. They were half way up to Kingston, when a boat containing a party of armed rebels, who evidently suspected their errand, darted out behind them from the other side of the river, cutting off their retreat and very nearly capturing them. The negroes pulled quickly for what they supposed to be the shore: but it proved to be an island and they were surrounded. It was with the greatest skill and bravery that they escaped. They returned thoroughly exhausted; yet in a few days, they started again on a similar errand.

AN EXPEDITION PLANNED BY A FREEDMAN.A man named Sam Williams, came one evening, and desired to speak to me concerning a plan, by which he said we might catch several hundred of the rebel soldiers. He took the map, and describing the location of the enemy, and the character of the country, pointed out a bye-road through the swamps, by which, he said, they could readily be approached and surrounded. He planned out all the details, and made it as clear as possible. In due time, General Foster ordered the plan to be carried out. There were three regiments in the expedition, Williams riding ahead, surrounded by twenty cavalry; it unfortunately

happened, however, that the commander decided to take another road. As the little party of twenty, ahead, were passing a church, about sixty rebels sprung out from the road side and fired upon them. Nearly all the twenty were thrown from their saddles. For a moment, all was confusion; but our troops coming up, soon put the rebels to flight. Williams, in the excitement, escaped to the woods: and, after twenty-four hours hard experience, returned. The Colonel commanding said, in making his report, that “if he had followed Samuel William's advice, as he should have done, they would have been entirely successful.” And the rebels said to two of our soldiers whom they took prisoners, and afterwards exchanged, that “if they could only have caught that negro, they would have roasted him alive.” An officer said in the presence of one of the Generals that, “There was not a braver man in North Carolina, within our lines.” The following is a copy of a paper given to this man, by the two chief officers of the 3d New York Cavalry Regiment, to whom he acted as guide.

“HONORABLE MENTION.”

St. Nicholas Hotel,

New York, 18th Sept., 1862.

This is to certify that the bearer, Samuel Williams, colored man, served the United States Government as guide to my Regiment on an expedition out of Newbern, N. C., in the direction of Trenton, on the morning of the 15th of May, and performed effectual service for us, at the imminent risk and peril of his life, guiding my men faithfully and truthfully, until his horse was shot under him, and he was compelled to take refuge in a swamp.

He was of great service to the Union cause while in North Carolina.

S. H. Mix,

Col. 3d N. Y. Cavalry.

Witness,

Vincent Colyer,

Superintendent of poor Dept. of N. C.

I certify that I am personally acquainted with the man within named, that he was guide of the expedition to Trenton, N. C., and bore himself in a creditable manner.

C. Fitz Simmons,

Major 3d N. Y. Cavalry.

It was the repeated demand for passes by the men, to go for their wives within the enemys lines, that led me to think of this scouting service. One day two young men called for passes for this purpose. Their wives lived in the neighborhood of Kingston. I acceeded to their request, and on their promising to visit the enemys camps, and their expressing a desire to have a weapon to defend themselves with, I gave them a revolver. They were absent some three weeks, or more, when several refugees, arriving from Kingston informed us that one of these young men had been shot, and taken prisoner. He had somewhat rashly exposed himself by visiting his wife in early twilight, and had been discovered by her master who was a noted rebel, who laid wait for him, and when the young man emerged from his wife's cabin, he shot him. They bound him hand and foot, and placing him on a hand cart drove him through the streets of Kingston to the town jail. Our informer stated that numbers of the town people crowded around the cart as it passed through the town on its way to the prison; but they would not let a negro approach him. They overheard their master say, however, that it was a negro whom the Yankees had armed and sent up as a spy. From that time forward the rebels were much more vigilant in posting guards through the woods; and several of our scouts were compelled to return without effecting anything.

ABILITY OF THE SCOUTS, OR INEFFICENCY OF OUR GUARDS.As an illustration, either of the extreme sagacity and ability of some of these scouts, or the carelessness of our picket guards, I will mention that I have known these spies on their return from their journeys, to arrive at my head quarters at different hours of the day and night, without having encountered one of our guards on the way.

A MISTRESS RELIEVED BY HER SLAVE.A family came into my house: the woman was dripping wet, hungry and tired, and we, of course, fed and clothed her. She had started down the Neuse River with her children, to “come to the Yankees.” They rowed, after twilight, down the river,

The Union Scout.until a breeze came up, which rocked the canoe badly, and they rowed for the shallow water, where, however, the waves were higher. She jumped out, and walking, kept the boat steady all the way—twelve miles—to Newbern. Her mistress said to her the night she came away, “Juno, this place is horrid; if you can make your way to the Yankees, do it. You see how poor we are, and how my children are compelled to suffer. Take this basket of eggs as a present to General Burnside, from me, and tell him if he can rescue a Union woman, for God's sake do it.” Juno also said, that one of her children had died on the plantation, and when her master, who was a rebel, sulkily refused to assist in its burial, her mistress, with her own fair, white hands, sawed out some boards, made a coffin, dug a grave and buried the little corpse.

This woman for weeks continued to importune me with tears on behalf of her mistress. At last, a boat's crew, going ashore for provisions, at the place where her mistress lived, rescued the woman and so relieved the heart of her faithful servant.

VALUABLE SUPPLIES OBTAINED.A large, six foot negro, came into camp one day, and said he had been hard at work in the enemy's camp, but by good luck had got away. He came one night, in his ramblings, upon a large pile of cotton, high as a house, covered with brush. Said he, “If you can give me a flat boat and some men, we can get that cotton.” We took a boat, twenty negroes, and one hundred men; every thing depending upon Charlie's caution and skill, and in three days the steamboat came back laden with the cotton, which was of great value to us as protection to our men in the gun-boats Its cash value was over $26,000.

(See Engraving, page 37,)

SLAVE ESCAPING BY FORGING PASSES.Another man came in who made 500 miles by a long circuit. He was able to write, and in that way he forged passes for himself the whole way. He had worked in the rifle factories, lately set up near Raleigh, N. C.—had lived near the rail road running from Raleigh to the West, and brought interesting

and valuable information of the passing of troops, with artillery and supplies, over the road. He was a good mechanic and a highly intelligent man.

FORAGING EXPEDITIONS.As I have previously related, the men frequently led foraging parties to places where supplies, necessary for the Department were obtained. In this way, boat loads of pine and oak wood for the hospitals and Government offices, a steam boat load of cotton in bales for the protection of the gun boats, and numbers of horses and mules, with forage for the same for the Commissary's Department, cattle, swine, sheep, &c., were obtained at no other cost than the small wages of the men. Without doubt, property far exceeding in value all that was ever paid to the blacks, was thus obtained for the Government.

Bringing in Supplies of Cattle.INDUSTRY OF THE BLACKS AS COMPARED WITH THE POOR WHITES.

Under my appointment as Superintendent of the Poor, from Major General Burnside, I had to attend to the suffering poor whites, as well as blacks. There were eighteen hundred men, women and children of the poor whites, who felt compelled to call for provisions at my office. To these eighteen hundred was distributed gratuitously, during three months, as follows:

| Flour | 76½ barrels. | Meal | 432 lbs. |

| Beef | 116 barrels. | Fresh Beef | 169 lbs. |

| Hominy | 4¼ barrels. | Peas | 549 lbs. |

| Coffee | 20½ barrels. | Salt | 219 lbs. |

| Sugar | 24½ barrels. | Hard Bread | 107 bxs. |

| Pork | 29½ barrels. | Molasses | 43 gal. |

| Bacon | 38 barrels. | Vinegar | 6 gal. |

| Rice | 37 barrels. | Soap | 39 lbs. |

| Candles | 379 lbs | Beans | 7½ lbs. |

| Tea | 65 lbs |

While to the seventy-five hundred poor blacks, over four times the number there that were of the whites, there was called for and given in the same time as follows:

| Flour | 19 barrels. | Hominy | 237 lbs. |

| Sugar | 7 barrels. | Beans | 369 lbs. |

| Coffee | 5 barrels. | Peas | 308 lbs. |

| Rice | 8 barrels. | Hard Bread | 3262 lbs. |

| Beef | 4½ barrels. | Soap | 805 lbs. |

| Pork | 16½ barrels. | Salt | 44 lbs. |

| Candles | 27½ lbs. | Fresh Beef | 19 lbs. |

| Tea | 4 lbs. | Molasses | 31 gal. |

| Meal | 433 lbs. | Vinegar | 15 qts. |

Or an average in most articles of sixteen times as much, was called for by the poor whites, as was wanted by the poor blacks. At that time, work was offered to both—to the whites at the rate of $12.00 the month, to the blacks at the rate of $8.00 the month.

MISCEGENATION AT THE SOUTH.

As Superintedant of the poor, the duty of burying the dead was committed to me. In the fulfilment of this duty I was one day called upon to provide a coffin and grave for a young colored man, who had died under somewhat suspicious circumstances. He had been, apparently, in perfect good health but six hours before his death; and the only cause assigned for his decease was, that he had run a small tack in his foot a day or two before, and that possibly he had died of lock jaw.

On visiting the house, or hovel, on the outskirts of the town, where his body lay, I found that he had been living with, and working for a man who was said to be his owner, that this master, though the owner of twelve or fourteen slaves, was living in that hovel, in open concubinage with a negro woman who was not his slave; that he had previously lived, at periods of a year or two with other negro women, and that on one or two occasions he had quarreled with them and threatened their lives. As these women were still living in huts in the immediate neighborhood, I visited them, and found that the slave owner had, in one instance, made an attack with a knife on his black paramour, and that she had barely escaped with her life. In proof of this assertion she exhibited her dresses and showed the slits in them made by the knife.

The hovel in which this master and his black partner lived, was one story in height, with one window about two feet square, a mud chimney with a barrel on top, a broken door, covering a lop-sided entrance leading to an interor, consisting of but one room, without carpet, with two or three rickety chairs, a small pine table and other wretched furniture.

The man fled on our arrival, and though we afterwards found him, the difficulties of a post mortem examination sufficiently accurate to prove the presence of poison on the body of the deceased, and the press of occupation upon the few surgeons in the department, compelled us to release him.

THE LIGHT COLOR OF MANY OF THE REFUGEESIs a marked peculiarity of the colored people of Newbern. I have had men and women apply for work who were so white that I could not believe they had a particle of negro blood in their veins, except upon the broad belief according to the

declaration of St. Paul “that God had made of one blood all the nations of the earth.” I have spoken elsewhere of the great beauty of many of the quadroon girls who attended my school for the more advanced scholars. Many of them were as white and as comely as any Italian, Spanish, or Portuguese beauty. So remarkable is the difference in the color of the blacks of the South from these of the North, that the conviction is constantly forced upon the mind, that slavery if left to itself but a few generations longer would have died out of itself, from this cause alone.

INDUSTRY OF THE WOMEN AND CHILDREN.Industry of the Women and Children.

The women and children supported themselves with but little aid from the Government, by washing and ironing, cooking and making pies, cakes, &c., for the troops. The few women that were employed by the Government in the hospitals received four dollars a month, clothes and one ration.

ARRIVAL OF THE FREED PEOPLE.

Arrival of the Freed People.

The freed people came into my yard from the neighboring plantations, sometimes as many as one hundred at a time, leaving with joy their plows in the field, and their old homes, to follow our soldiers when returning from their frequent raids; the women carrying their pickaninnies and the men huge bundles of bedding and clothing, occasionally with a cart or old wagon, with a mule drawing their household stuff. They were immediately provided with food and hot coffee, which they seemingly relished highly, for they were usually both hungry and tired from their oftentimes long journeys and fastings. Their names were at once registered in the books; and after one night's rest, they would find habitations in the deserted town, and be industriously at work, the men for the Government, and the women for themselves.

Those in the neighborhood of Newbern were ordered to report at my office, as soon as they arrived within our lines. They obtained quarters in the outhouses, kitchens and poorer classes of buildings, deserted by the citizens on the taking of Newbern. They attended our free schools and churches regularly and with great eagerness. They were peaceable, orderly, cleanly and industrious. There was seldom a quarrel known among them. They considered it a duty to work for the United States Government: and though they could, in many cases, have made more money, at other occupations, there was a public opinion among them that tabooed any one that refused to work for the Government. The churches and schools established for their benefit, with no cost to tbe Government, were of great value in building up this public opinion among them.

My office was in a fine old homestead, gracefully shaded with large elm, walnut, and pine trees, with a garden of over an acre, filled with plum, peach, apple, and fig trees; with beds of lilies, tulips and rose bushes, heavy with clusters of those fragrant flowers, The trees were filled with mocking birds and other charming feathered songsters.

The consequence of this system, of having all the refugees report at the one central office, and of having their names, ages previous occupation, number in family, where they came from, and the place to which they were assigned to work, or where they went to reside, was, that we could not only always readily find them for the special duty for which they were fitted, whenever they were wanted, but, they never became vagrants or objects of charity on our hands. As I have before remarked, we never could get enough of them, consequently those appeals for “old clothes, money, books, &c.” which has been heard so often from other Departments, were not necessary, and for that reason, were never made from the Department of North Carolina, while I had charge of the freed people. The only appeal that I ever made, was privately, through Mr. Larned, for some medicines for the hospital which the medical director of the department had not in his stores at the time, or he would have supplied me with them. On two occasions I was offered a salary by the freed-people, if I would take charge permanently of the congregation of St. Andrew's Colored Church, in Newbern, which fact plainly proves they were no “paupers.”

The only clothing that was distributed by the Government to redeem its promise of “clothes” as well as $8.00 per month, during my term of office, was four hundred suits of captured rebel uniforms, and a good supply of large size soldiers’ shoes, turned over to me by the regimental quartermasters because they would not fit the white soldiers of our army, yet the money the freed-people earned by their well directed industry, enabled both the men and women to dress decently, and in no way to suffer from the lack of clothing. The Government, however, should have redeemed its promise, as the blacks thoroughly knew their rights.

I was succeeded in office by the Rev. Mr. Means, whose faithfulness in the work was proven by his laying down his life in the service, and the present superintendent, the Rev. Horace James, is one of the best friends of the freedmen to be found in the country.

CHURCHES OPENED.Soon after our arrival in Newbern, I was invited by the Elders of the African Methodist Church to hold services with them. The local preacher, a white man, who had formerly presided over them, was still there and preached every Sunday morning; and at three in the afternoon, they had their class meeting. Notwithstanding these two meetings were well attended, the services over which I was invited to take charge at five o'clock were usually crowded. The church had a gallery all round, and seated about six hundred. Another church edifice, a Baptist, which held three hundred and fifty, and had been closed some years, I opened, and here also I had a full attendance every morning, at the same time the Methodist Church services were being held.

On Roanoke Island, the blacks, for want of a church edifice, had constructed a spacious bower, cutting down long, straight, pine trees and placing them parallel lengthwise for seats, with space enough between for their knees—constructing a rude pulpit out of the discarded Quartermaster's boxes, and overarching the whole with a thick covering of pine branches. Many of their colored preachers exhort with great earnestness and power, and usually present the Gospel with simplicity and truth.

Cotton Hoards in the Swamps.CHRISTIAN PIETY OF THE BLACKS.

One peculiarity of great, if not vital importance that must be considered in forming a plan for the proper and judicious treatment of this people, is their earnest and loving faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. Without the ability to read, except in a very few instances, with but little leisure to attend places of public worship, and through long and painful years of oppression, they have been blessed by the grace of God, with a simplicity and clearness of understanding of the fundamental doctrines of the truth of salvation as it is in Jesus Christ, that is most astonishing. If one would learn what precious comfort may be found in Christianity, in the midst of the severest trials, with which human nature can be afflicted, let him go among this people. In the evening after the toils of the day are over, you will hear from the cabin of nearly every family, the sweet sound of hymns, sung with plaintive and touching pathos to some familiar tune, and listen quietly as you pass by, and you will hear it followed by the earnestly beseeching voice of prayer. Their religious meetings are usually crowded. Before the rebellion broke out, these meetings had been discouraged by the State authorities, whether from fear of the slaves I cannot say, though I always heard this given as the reason.

THEIR DISLIKE OF THE REBELS.When our army took Newbern, about fifty of the enemy's wounded under the care of two of their surgeons fell into our hands. These two doctors made constant complaints of their inability to get any of the negroes to assist them in the hospital. As we found no difficulty in having always plenty of excellent help from the blacks in that way, remembering how cruelly many of our wounded at the previous battles of Bull Run and elsewhere had been treated by the rebels, and desirous to set a good example, I tried hard to remedy the defect, and sent a number of negroes to their assistance, but all to no purpose. At last, at a prayer-meeting one evening, I appealed to their religious faith, calling their attention to those passages in our Saviour's teachings, when he says: “If thine enemy hunger feed him, and if he thirst, give him drink;” and then

told them of the euemy's hospital, and calling their attention to the fact, that these misguided people were now in our hands as prisoners of war. I asked them if there were not four Christian men among them, who would, for the sake of the Saviour, forego their dislike, and volunteer to take care of the hospital for us. Four gave in their names, and served in the hospital faithfully for two months, until the rebels were exchanged.

The duties of the day, at my office, were always opened with prayer, singing and reading a chapter of the Bible, and every black about the place, usually from ten to twenty, attended these services cheerfully. For quiet, cleanliness and order, I will venture to say, the head-quarters of the Superintendent of the Poor, though frequently crowded with hundreds of poor whites and blacks, compared favorably with any other office in the Department.

SPREAD OF SMALL POX PREVENTED.A colored servant, from the North, of one of the officers of the 3rd N.Y. Heavy Artilery, was one day sent to me by the Surgeon of the regiment, after he, the servant, had broken out with the Small Pox. I found that I could get no doctor, either in the army or in the town, to see to him, and the negroes had the greatest dread of this disease. After being compelled to nurse him myself, at no little trouble of changing my clothes each day that I visited him, for fear the blacks would catch it, I was led to inquire as to how many of them had ever been vaccinated; and found, to my surprise, that hardly one of them replied in the affirmative. Finding that some of the Surgeons of the Army had a good supply of vaccine matter, I stated the fact to Dr. Clark of Worcester, Mass., and he kindly offered and immediately proceeded to vaccinate all the refugees in Newbern.

After a vain search of several days for a nurse, at last, I found an old black woman who had had the small pox, and she consented to take charge of him. I had bim conveyed to a hut on the outskirts of the town, some distance from our office. One very rainy day the old nurse came all dripping with wet and bent with age, to get some comforts for her patient, and on my pittying her forlorn condition and admiring her faithfulness,

she exclaimed with an earnestness and pathos, I shall long remember. “Yes! The blessed Jesus did not die on the Cross for the white man only!”

The Old Nurse.HOSPITAL FOR FREEDMEN FOUNDED.

This case of small pox, above referred to, induced me to apply to General Burnside to have an hospital for the blacks under Goverment employ, established, and he at once gave his consent; and General Foster issued an order for Dr. Clark to take charge of it. About one hundred patients were successively cared for in it, and a few died. Most of the medicines were furnished by some liberal people at the North, through an application made to them by Mr. B. R. Larned, the General's private secretary.

With the exception of my excellent Assistant, Mr. Mendell—a soldier detailed from a Massachusetts Regiment—I had colored help for every purpose. My Assistant Secretary, Amos Yorke, from whom I give a letter in another page, was an intelligent and worthy Christian. Another, Samuel Williams, of whom I have previously spoken as guide to a regiment, was out-door overseer. At times, he had charge of three hundred men, and they rarely ever quarrelled. His father, Jacob Coonce,

was store-keeper. He was intelligent and trustworthy: thousands of dollars worth of goods went through his hands, in small parcels, and were conscientiously accounted for.

THEIR USEFULNESS AS SERVANTS, ETC.One of the services, most generally useful, rendered by the freedmen in North Carolina, and I presume it is the same wherever the Union army has gone, has been their work about the camps. As servants to the officers and men, in waiting upon them, cooking, splitting wood, as teamsters, hostlers, porters, &c., who can estimate the amount of good they have done, or the number of lives they have saved. This labor, too, was generally performed with so much cheerfulness and good humor, that they were very popular in the army.

Chopping Wood and Cooking for the Hospitals.SCHOOLS FOR WHITE CHILDREN

Having charge of the poor white people, I had opened a school for the instruction of their children, in which I had engaged a young lady teacher, a resident of the town, to instruct about seventy white children. This school, together with nearly all that I was privileged to do for the poor white people, was a source of constant joy to me. It was the delight also of many of the officers of the Union Army, and was visited by them, Generals Burnside and Reno, contributing something to its support. I could say much of the gratitude and affection with which the officers and men of the Union Army were received by the poor white people of Newbern, and of the estimable character of many of them; but, I am writing in this report, only of the blacks.

SCHOOLS ESTABLISHED.—THE COLORED SCHOOLS.The colored refugees evinced the utmost eagerness to learn to read. I had taken with me some spelling books and primers, and these were seized with great avidity. The sutlers also sold large numbers of these and other books.

With the consent of Gen. Foster two evening schools for the colored people were commenced by me, over eight hundred pupils, old and young, attended nightly, and made rapid progress. In the larger school of six hundred, I placed those who did not know the alphabet, who could hardly spell; in the smaller of two hundred, I had the most advanced, those who could read. Some of the scholars in this latter school were very bright, and among the young women were a number of quadroons, some quite beautiful.

In the school for those who could read and write which usually had an attendance of between one and two hundred, I used books, slates, &c, with teachers placed over classes.

The two African churches at Newbern, were used for our school rooms. I took a large white cotton sheet, and with black ink wrote in large letters some brief passage from the scripture, such as “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you,” and suspending it over the pulpit, where all could see it, with a large pointer I made them all go over, first the letters,

then the syllables, then the whole sentence together, and usually in half an hour, I could get the whole school to know it by heart.

The exercises were opened with a prayer and a hymn, and closed with a single verse and the benediction.

The soldiers in the New England regiments kindly volunteered as teachers. I had some thirty or more from the 25th Massachusetts Volunteers. Some of these young men were graduates of the first colleges in the North.

These schools had been under way about six weeks when Governor Stanley arrived. On his making known to me his opposition to their continued existence, I stopped them.

Governor Stanley was appointed Military Governor of North Carolina by President Lincoln in the early part of May 1862, and in his political policy he followed that of the Border States, which aimed to restore the Union and preserving slavery.

The closing of these schools is thus described by the Newbern correspondents of the Times, who writes under date of May 31, and from whose letter we copy:

CLOSING THE SCHOOLS FOR CONTRABANDS.“The schools established by Mr. Colyer for the instruction of the colored people were suddenly closed on Wednesday evening. It was the first administrative act of the new Governor, since whose advent the military authority seems, to a great extent, suspended. At the Methodist church in Hancock street in this city. Mr. Colyer addressed the contrabands, saying:

“These schools are now to be closed, not by the officer of the army, under whose sanction they have been commenced, but by the necessity laid upon me by Governor Stanley, who has informed me that it is a criminal offence, under the laws of North Carolina, to teach the blacks to read, which laws he has come from Washington with instructions to enforce.”

The teacher said he hoped that the schools would be closed only for a brief time, and exhorted them to submit patiently to the deprivation like good, law abiding people, such as they had always proved themselves to be. Those who followed the injunction before them, on the pulpit and trusted in the Saviour, who had given the command, would not only have this blessing restored to them, but must ultimately enjoy even greater blessings than this.

The First Public School for Colored People in North Carolina, Established by Vincent Colyer, April, 1862The old people dropped their heads upon their breasts and wept in silence; the young looked at each other with mute surprise and grief at this sudden termination of their bright hopes. It was a sad and impressive spectacle. Mr. Colyer himself could hardly conceal his emotion. A few moments of silence followed, when, as if by one impulse, the whole audience rose and sang with mournful cadence, “Praise God from whom all blessings flow,” and then shook hands and parted.

The school at the Baptist Chruch, where the more advanced scholars were placed, was closed in a similar manner.”

INDIGNATION OF THE PEOPLE OF THE NORTH.This closing of the colored schools attracted great attention throughout the country, and on coming North soon after, on a brief leave of absence, I found that the Rev. Dr. Tyng, Mr. Caldwell, of Pennsylvania, and other active Christians, had called the attention of the Government to it.

The press was loud in its denunciations of Governor Stanley, and of the Government for appointing men with such views, and I was called upon to address several public meetings, held for this special object.

The Governor had not only suggested to me to close my schools for the blacks, but had returned several fugitive slaves to their owners. Up to the time of Governor Stanley's arrival, the refugees had been all practically free, none had been returned to their masters by General Burnside, so that Governor Stanley's course appeared all the more odious.

This returning of the refugee slaves to their masters is thus described by Mr. Elias Smith of the N.Y. Times, writing from Newbern, May 31st, 1862.

SENDING BACK THE BLACKS.“Yesterday the Governor was waited upon by large numbers of the residents, in and out of town, who congratulated him upon the auspicious beginning of his administration. Among others, several persons applied for the restoration of their fugitive property who have sought protection from the tyranny of the plantation within our lines. One Nicholas Bray, living a few miles from town on the Falmouth road, obtained an order to carry off his slave woman. With his wife he proceeded to a building where one of them was staying, and dragged

her forth and drove away with her to the plantation. Her sister, a bright mulatto young woman of unusual attractions, hearing of the proceeding, was made almost frantic, and sought asylum at the only place she knew—the headquarters of the poor. Elated at his success, Bray drove up and without ceremony began a search of the premises. Mr. Colyer at the time was away. Apprised of his coming, Harriet flew with lightning speed, and concealed herself in an out-building almost under the eaves of General Burnside's headquarters. Not finding the object of his search Bray drove off, probably to renew the search at a more convenient season. Harriet is only seventeen years of age, and Bray asserts that he has been offered fifteen hundred dollars for her.

Bray is a brother-in-law of A. G. Ewbank, the quartermaster of the rebel militia lately in this place. He is a well known rebel; was mustered into the service, it is said, and only escaped taking part in the battle of Newbern on account of some alleged injury to his back. He promised to take the oath of allegiance.

Several other orders were given for the capture and taking away of slaves from the town. Four were reported to have been captured and carried out of our lines yesterday.

FLIGHT OF THE NEGROES.Flight of the Negroes.

“Frightened at the turn of affairs, a number of the slaves who have congregated in the town had scattered like a flock of frightened birds.

Repairing Railroad, etc.Some have taken to the swamps, and others have concealed themselves in out-of-the-way places. A perfect panic prevails among them. The greater part who were employed on the fortifications are so much alarmed at the prospect of being returned to their enraged masters, and being punished, that they are of little use as laborers.

It is believed that many will find their way to the rebel lines, and, in order to make friends with them, will reveal important facts touching the condition of affairs in this department. The slaves express the greatest horror at the prospect of being sent back to their old homes, and say that they will be unmercifully “cut up” for having absconded. One old man of sixty told me to-day that he would rather be placed before a cannon and blown to pieces than go back. Multitudes say they would rather die.”

INTERVIEW WITH THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES.Soon after coming North, on the 5th of June, 1862, I visited Washington, and in company with the Hon. Charles Sumner, called upon the President. Mr. Lincoln, received me courteously, and as if he anticipated the nature of our errand. After introducing the subject in general terms, Mr. Sumner asked me to repeat the substance of the conversation between Governor Stanley and myself. This I did. When I came to that part of the Governor's declaration where he states that he had instructions to enforce the local laws of North Carolina, the President remarked that that was a misapprehension on the part of the Governor that he could have had no such instructions, and if he had they were unlawful. The President then inquired as to the nature of my work and the character of my mission, which as briefly as possible I told him. Mr. Sumner then requested me to state the way in which the Schools were closed, which I did. When I told the President of the return of the freed people to their former masters, he exclaimed with great earnestness of manner:

“Well this I have always maintained, and shall insist on, that “no slave who once comes within our lines a fugitive from a “rebel, shall ever be returned to his master. For my part I “have hated slavery from my childhood.” I could not help saying, thank the Lord for that.

On our way home Mr. Sumner said to me “you have seen more of the real character of the President, and have heard a

more important declaration than is usually seen or heard in a hundred ordinary interviews.”

When President Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Freedom, September, 1862, being about three months after these things occurred, and included North Carolina in the list of States to receive the immeasurable blessings of that beneficent measure, we could not but feel that the hand of God was in it, and that He had, perhaps, been pleased to use us as an humble instrument, to help bring about this glorious result.*

On my return to Newbern, Governor Stanley assured me that I had quite misunderstood him, and desired me to state this for him, to the public, which I did most gladly in the following letter to the New York papers:

Newbern, N. C., June 24, 1862.

His Excellency Governor Stanley takes exception to the statement in my speech in New York, to the effect that I said that he intended to enforce the laws of North Carolina, and desires me to say “that I misunderstood him; that he never intended to enforce those laws, and that with regard to interfering with my schools for colored people, or the return of fugitive slaves to their masters, he would await speciüe instructions from the Government at Washington, D. C.,” which statement I am most happy to make.

Vincent Colyer, Superintendent of the Poor.

*The Boston Liberator publishes a letter from the late Owen Lovejoy, addressed to Wm. Lloyd Garrison, under date of Washington, Feb. 22d, 1864. In this letter Mr. Lovejoy says:“Recurring to the President, there are a great many reports concerning him which seem to be reliable and authentic, which, after all, are not so. It was currently reported among the anti-slavery men of Illinois, that the emancipation Proclamation was extorted from him by the outward pressure, and particularly by the delegation from the Christian Convention that met at Chicago. Now the fact is this, as I had it from his own lips: He had written the Proclamation in the summer, as early as June, I think,—but will not be certain as to the precise time,—and called his Cabinet together, and informed them that he had written it, and he meant to make it; but wanted to read it to them for any criticism or remarks as to its features or details. After having done so, Mr. Seward suggested whether it would not be well for him to withold its publication until after we had gained some substantial advantage in the field, as at that time we had met with many reverses, and it might be considered a cry of despair. He told me he thought the suggestion a wise one, and so held over the Proclamation until after the battle of Antietam.

General Burnside's Private Carriage.Many of my friends misunderstanding this letter, supposing it to be a retraction on my part, were much offended at me; but, if they will look at the wording of it they will perceive that I simply say that “Governor Stanley requested me to say that I misunderstood him.” I did not say that I had misunderstood him—for that I never had. What I had stated of his interview with me, and of his declaration that “he was instructed at Washington, to enforce the local laws of North Carolina,” was strictly true.

Governor Stanley in a letter which he addressed to some rebel official at Raleigh, N. C, published soon after, endeavored to give it this interpretation by intimating that I retracted; but by doing this he only committed himself all the more irrevocably to the Free State Policy, into which he had, seemingly, been driven by this manifestation of popular feeling at the North. As the friends of the oppressed had obtained a signal advantage, and the right of the refugee slaves to their freedom, and to be educated, had been efficently secured, in the flush of conscious victory to our cause, perhaps I was not so careful in the wording of my note as I might have been.

The searching of my premises for Harriet, the slave girl, by Bray, and his carrying back of another, having an order in writing from Governor Stanley, permitting him to do so; the order given to the captain of the steamer “Haze,”—and it was said to others—forbidding him from taking any freedmen North, under pain of the confiscation of his vessel; the promise to Mr. Perry, of $1,000 for the man Sam Williams, whom I had taken North with me; the demand upon General Burnside for that amount, because I had not returned Sam; the expatriation of Mr. Helper; all these acts of Governor Stanley, which were known to hundreds, make it unnecessary for me to say any more.

RESIGNATION OF GOVERNOR STANLEY.His Excellency resigned his office on the receipt of the President's proclamation.

SUPERINTENDENTS OF THE FREEDMEN.The freedmen at Roanoke Island and vicinity were under the immediate control of Col. Rush Hawkins, of the Zouaves,

9th N. Y. Volunteers, commandant of that post. Sergeant Thompson was their Superintendent. Those on the rail road between Carolina City and Newbern, and at the former place were under Capt. Hall, A. Q. M. to Genl. Reno's Division. Those at Washington were under Col. Potter, commandant of the post—Mr. Phillabrown, the engineer, being their Superintendent. Those at the fort and bridge at Newbern, the former under Mr. J. Cross, as Superintendent, and the latter under Mr. Wilson, the builder.

JUSTICE TO THE BLACKS UNDER GENERAL BURNSIDE.All those gentlemen, without exception, were just, kindhearted and humane men, as their various orders, rules and regulations, issued for the protection of the blacks, would testify, if we had space for them here. And it is to this fact, namely, the great kindness of nearly all the officers under Genl. Burnside, that the well-known activity, usefulness, and contentment of the blacks in the Department of North Carolina are to be attributed.

GENERAL BURNSIDE'S HEADQUARTERS, NEWBERN, N. C.I have introduced the picture of General Burnside's Headquarters at Newbern, because it is associated in my mind with so much that was appreciative and kind hearted towards the negroes. Many a faithful scout and footsore refugee, fresh from their hazardous journeys through the enemy's lines, have I taken into those headquarters. Whether at early dawn or twilight, high noon or midnight, it was all the same, the General received us promptly, and usually with a cheerful welcome. Sometimes Generals Reno, Foster and Parks would be there, when the reception would be only so much the more cordial. General Burnside, though by no means an abolitionist, had too much sagacity to despise the services of the blacks, and is too large hearted a man to love slavery.

LOYALTY OF THE FREEDMAN.Of the seventy-five hundred colored persons under my charge in Newbern, I never knew but one who was suspected of disloyalty. This man was arrested on a charge of carrying salt to the enemy. After the most careful examination, he

General Burnside's Headquarters, Newbern, N. C.was acquitted, and left free to go to his home, which was at a small farm near the enemy's lines. Although he was entirely exonerated from all suspicion, he came to me and desired an interview, in order that he might remove all doubts from my mind, if I had any. He was greatly distressed at the mere suspicion.

Of all that I ever met, I cannot remember one that did not love liberty and hate slavery. All desired the success of the Union cause, and the overthrow of the rebellion. Loyalty, with them, was seemingly a personal matter of the most intense importance to pray for, to work, and, if need be, to die for.

Of their ability to take care of themselves without the aid of a master, I will mention the one instance of the man Sam who came with me. In the ten months that he has been here to the North, he has earned money enough, besides his expenses, to buy two lots of ground back of Brooklyn, L. I., with three hundred dollars, and has eighty dollars in the Savings Bank.

GRATITUDE OF THE COLORED MEN.They are said to be dull and ungrateful. In refutation of this I append a letter from an escaped slave received since my return. The writer is a leading man among his people.

Newbern, August 27, 1862.

Mr. Vincent Colyer,

Sir:—With pleasure I write these few lines to inform you that I and my family are well, and to hope that you and your family are enjoying the blessings of good health.

I should have liked to have had a conversation with you before you left Newbern for good; but as I did not, I yet hope to see you again. There are great inquiries for you by the people of color in Newbern; they are much at a loss for they have no one now to apply to for comfort or satisfaction; no one that sympathizes with them as you did. Sir, I must say if the President of the United States was dead, the Union army could not mourn his loss more than the people of Newbern do the loss of you.

The Elders of St. Andrew's Chapel, J. C. Rew, Louis Williams, William Ryol, R. M. Tucker, give their best respects to you and your family.

I would like to say more, but I must close by saying if I should never meet you again in this life, I hope to meet you.

“In that world of spirits bright,Who take their pleasure there,Where all are clothed in spotless white,And conquering palms they bear.”I should be happy to receive a few lines from you.

Your most obedient servant,

AMOS YORKE.

When I returned in June, to re-open my schools, the colored people had generally heard of the manifestation of public feeling on the subject of the closing of these schools by Governor Stanley, and my interview with the President on the subject. They had also heard many bitter and ill-natured things said about me by our enemies in Newbern during my brief absence. Yet as soon as they heard of my arrival there, they came, in the face of the persecution to which both they and I were, for the time, subjected, and brought me presents of flowers, cake, fruit, chickens, eggs, &c., and manifested their affection in many ways. They were proverbially respectful in their behavior to every one; but they were particularly so to me after that; the men touching their caps, the women courtesying. As the city was then full of them, I believe I received more salutations from the blacks than the Commanding General did from the whites.

I cannot better close this brief report than by calling the attention of the Christian reader to the engraving on page 61, representing some of the services rendered by the freed people on the evening and morning after the battle of Newbern, in nursing and attending the sick and wounded soldiers of our army.

Services of the Freed People on the Battle Field.BUREAU FOR FREEDMEN'S AFFAIRS.

You have been pleased to do me the honor to ask my opinion on the method of organizing a Department for the general supervision of these worthy people, in their present condition. It seems to me a very simple matter. Act towards them preciseiy as though they were white people.

First, the Government must protect them: positively, unequivocally, by fixed, clearly defined, strong orders from the U. S. Government through the War and Navy Departments. These loyal and, at the present time, invaluable people, must be treated humanely and justly, as good loyal freemen. The same punishments that are inflicted when white men are injured, must be awarded to those who injure the blacks. And the same reward, be it wages or honorable mention, that is given to the former who serve the Government faithfully, must be given also to the latter.

To enforce these orders from the War Department, I think the plan you spoke of a good one, to have a Bureau and Central office at Washington, D. C., with full appointment of clerks, District and Assistant Superintendents, with clerks and overseers to aid them at their respective places, to report to this Central Bureau. But let it be a Bureau for the protection and elevation of the Blacks, and not merely for their restraint. The details necessary to perfect such a plan could be readily obtained of the present Superintendents, and other men of experience.

You would thus bring under one proper central office, and under one uniform general system, that which is now loose, irregular and unmanageable. It is essential to have a place of refuge for the blacks on their first arrival within our camps, and an office where all the able-bodied men, with their names, ages, occupations, &c., shall be recorded, to which all the departments of the army and navy can apply when they need men.

The whole system to be abandoned, if possible, when the war is over.

With high regard,

Very respectfully yours,

VINCENT COLYER.

To Hon. ROBERT DALE OWEN,

Chairman of Freedman's Inquiry Commission.

INDEX.

| PAGE. | |

| Ability of Scouts, or inefficiency of Guards | 26 |

| An Escape without Discouragement | 24. |

| Arrival of Freed People | 34 |

| Bureau for Freedmen's Affairs | 63 |

| Character of the Scouts | 16 |

| Churches Opened | 36 |

| Christian Piety of the Blacks | 39 |

| Closing of the Schools by Governor Stanley | 44 |

| Dislike of the Rebels | 39 |

| Expedition Planned by a Freedman | 24 |

| Fears of Flank Movement Dismissed | 23 |

| Foraging Expeditions | 30 |

| Gratitude of the Colored People | 59 |

| Hints to Scouts in Future Service | 24 |

| Honorable Mention | 25 |

| Hospital Founded | 41 |

| Industry of the Blacks compared with the Poor Whites | 31 |

| Indiguation of the people of the North | 47 |

| Interview with President Lincoln | 51 |

| Justice to the blacks under Gen. Burnside | 56 |

| Loyalty of the Freed People | 56 |

| Mistress Rescued by her Slave | 26 |

| Miscegenation at the South | 32 |

| Negroes not a Burthen | 6 |

| Number of Freed People in North Carolina | 6 |

| Old Nurse | 41 |

| Refugees from Alabama | 22 |

| Refugees from South Carolina | 22 |

| Resignation of Gov. Stanley | 55 |

| Superintendents of Freemen | 55 |

| Services as Spies | 10 |

| Story of Wm. Kinnegy | 16 |

| Slave Escaping by Forging Passes | 29 |

| Small Pox Prevented | 40 |

| Schools for White Children | 43 |

| Schools for Colored People | 43 |

| Sending back the Slaves | 47 |

| The Work done by them | 9 |

| Usefulness as Servants | 42 |

| Valuable Supplies Obtained | 29 |

| PAGE. | |

| Arrival of Freed People | 34 |

| Blacksmith Shop | 11 |

| Bringing in Supplies of Cattle | 30 |

| Cotton Hoarding in the Swamps | 37 |

| Chopping Wood and Cooking for Hospitals | 42 |

| Furney Bryant as the Refugee | 13 |

| Furney Bryant as Union Soldier | 14 |

| Furney Bryant Defending Newbern | 18 |

| Freedmen as Union Scouts | 23 |

| First School for Colored People in North Carolina | 45 |

| Flight of the Negroes | 48 |

| General Burnside's Private Carriage | 53 |

| General Burnside's Head-Quarters, Newbern | 57 |

| Industry of the Women and Children | 33 |

| The Old Nurse | 41 |

| Placing the Stockade in Building the Forts | 7 |

| Repairing Railroads, etc. | 49 |

| Services on the Battle Field | 61 |

| The Freedman | FRONTISPIECE. |

| The Union Scout | 27 |

| William Kinnegy bringing in his Family | 21 |

Heckman Bindery, Inc. Bound-To-Please OCT 02 N. Manchester, Indiana 46962

Genealogical research