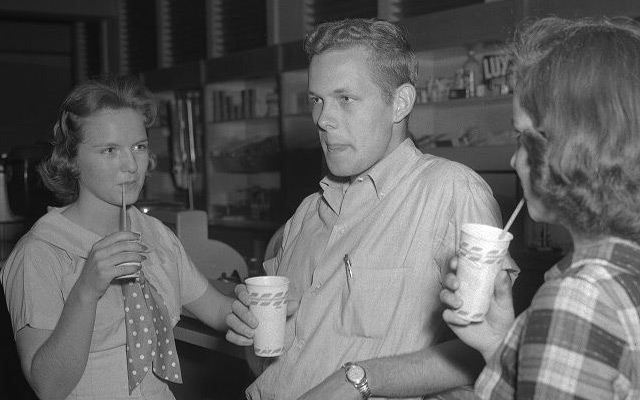

| Interviewees: | Jack L. and June B. Wallace |

| Interviewer: | Joyce J. Newman |

| Date of Interview: | May 21, 2008 |

| Location of Interview: | Bath, N.C. |

| Length: | MP3 - 71 Minutes; 07 Seconds |

Joyce Newman:

This is Joyce Newman and I'm in Bath, North Carolina, with Jack and June Wallace and we're doing an interview for the East Carolina Centennial Oral History Project and they've given us permission to tape this interview and put it in the archives and use it for research purposes. So I guess first if you could just maybe Mr. Wallace begin by just sort of saying where you're from, where you grew up, who--you know what was your family--just sort of where you came from?

Jack Wallace:

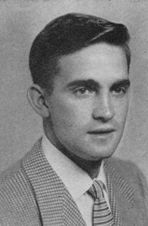

Don't you want to start? I'm Jack Wallace and I grew up in the Bath community. I was born in 1927. I'm one of 10 children. I'm the fourth from the bottom; I'm the oldest one at this time. We've lost all of the other children in our family. I was the first one to go to college. I had the opportunity to go. My older sister and older brother and my other older sister probably had more intelligence than I could ever muster, but they didn't have the opportunity to go. I entered East Carolina in 1947 after graduating from Bath High School in 1945 and I sailed in merchant ships for two years, saved enough money for my first year at East Carolina in 1947.

Joyce Newman:

Okay; and your father was a--?

Jack Wallace:

My father was a farmer.

Joyce Newman:

So you grew up on a farm?

Jack Wallace:

I grew up on a farm raising tobacco, corn, beans; he was a tenant farmer. We didn't own our farm. When I was 13 years-old we--he purchased our first farm because he had enough help because he could work it.

Joyce Newman:

So that was from the children?

Jack Wallace:

That was from the children. Dad and myself did most of the work because the brother just above me had knee problems all his life and he couldn't work on the farm and the girls didn't want to work on the farm, so dad and myself did the heavy work. And dad paid for that farm in three years and we thought that was really the thing to do.

Joyce Newman:

And that would have been in the '30s--late?

Jack Wallace:

Dad bought it in--dad bought this farm--it was in the early '40s when he bought the farm. We--we tenant farmed in other areas that other people owned and dad did the work and the others made the money and we made a living. I started school in Bath in the first grade; went all the way through to grade eleven. North Carolina had only 11 grades when I graduated in 1945 and the State of North Carolina changed to 12 grades in 1946 and that was an accomplishment I think for the State. But I went to East Carolina in 1947 and left home and I said, "Dad, now can you let me have a few dollars?" He gave me $20 and I had to kick for the rest of it, but I had one talent that helped me. I could hit a baseball a mile and I could hit it hard and I got the first baseball scholarship that East Carolina ever gave in 1948.

Joyce Newman:

So--so you went directly from High School or--?

Jack Wallace:

No, I was out two years and sailed merchant ships.

Joyce Newman:

The merchant ships?

Jack Wallace:

Yeah; that was after--right at the end of World War II when the merchant ships were supplying the Marshall Plan and we carried goods to all of the countries in Europe. I remember well two trips we made to Italy and carrying coal and they didn't have any machinery to unload it and it was unloaded by hand--baskets. And I remember going to Dansk, Poland; they call it G'Dansk now. The Russians were in charge there and we carried 500 draft horses out of Savannah, Georgia, to Dansk, Poland, and we were told later on that the horses--we had taken them off the ship and they were put on rail cars and carried directly into Russia. [Laughs] So that was part of the Marshall Plan at--at the time.

Joyce Newman:

So you went to Bath for all of the school?

Jack Wallace:

All 11 years.

Joyce Newman:

Was it all one school?

Jack Wallace:

Yeah; it was--we called it--

June Wallace:

It was a Union School.

Jack Wallace:

--Union School or K through 12 that's what we had--a 1 through 12 then; K came in later, yeah.

Joyce Newman:

So when you graduated from High School did you have a notion at that point of wanting to go to college?

Jack Wallace:

I wanted to go to college; I wanted to go to college and play baseball but I didn't have any money and I didn't have--they were not giving baseball scholarships at--at East Carolina at the time. Wake Forest was giving scholarships and Wake Forest offered but I wasn't about to go to the Raleigh area. I wanted to stay close to home.

Joyce Newman:

So Wake Forest was in Wake Forest?

Jack Wallace:

That was in Wake Forest at the time; yeah.

Joyce Newman:

So you entered the Merchant Marines voluntarily?

Jack Wallace:

That's right; that's right--right after--right after high school.

Joyce Newman:

And did they have a program when you left them like the GI Bill or anything like that where they paid your tuition?

Jack Wallace:

No, no; now they had a program that you could go to Sheepshead Bay, New York, for training and I was there for about three months training to go on the ship and the pay was good. It was very, very good at that time, but my idea was to make enough money and drop out of there and go to school.

Joyce Newman:

So--so the desire was--was it as much to get an education or more because you wanted to play baseball?

Jack Wallace:

I think--I think the bottom line, I wanted to play baseball. But I had enough sense to know that you had to go to class and [Laughs] so it didn't take me long after going there that the class work became number one and baseball became number two.

Joyce Newman:

So what happened to your--how did your family feel about--?

Jack Wallace:

Well mom wanted us to go, but she was like most mothers at that time from farmers, they didn't have the resources to go and the scholarships were not available back in that area. It was a rarity when they--a college had funds to--to give scholarships and especially the--in the East.

Joyce Newman:

Uh-hm; so--so your older siblings were sisters except for one older brother?

Jack Wallace:

Well we had--no; there was six boys and four girls in the family, but I mentioned the two older girls. There were three older ones but two of them were brilliant; they

were--they were smart as [briars]. The older brother, well the oldest was--he was a good athlete, smart but there was no college available for him. So I was the only one in the family to go.

Joyce Newman:

How did you learn to play baseball?

Jack Wallace:

You know I never had any coaching at all. I think it was just instincts and [Laughs] a desire to hit a baseball hard and I could do that.

Joyce Newman:

Did they have like they do now the--the community games or--?

Jack Wallace:

Well that's--that's where you really started. No; they don't have what they call semi-pro baseball anymore and you might find it in some sections of the country but at this time in the '40s--'45, '46, '47, '48--semi-pro baseball was...was the thing right after World War II. There was no entertainment; you'd go to baseball games on the weekend and it was--it was the thing to do really.

Joyce Newman:

So they had the--the teams for all different ages like--?

Jack Wallace:

No, no; it was--it was adults.

Joyce Newman:

Adults?

Jack Wallace:

Now I was not an adult. I started playing with them when I was 13. And but most of them were in their 20s, veterans coming back; it was--it was the thing to do at that time.

Joyce Newman:

And when you were in the Merchant Marines did you see a lot of--?

Jack Wallace:

Well I went all over the world. That was the best education you could get. I remember one lady that was in Dr. Cummings' class. He taught World Geography at East Carolina. That name doesn't mean anything to you but he was a good one. And I had--I had

been anywhere in the world you could name it and this girl told me not many years ago--she said, "You know what I remember about you?" I said, "No; tell me." She said, "You knew more Geography than Dr. Cummings knew." [Laughs] "Well," I said, "I lived it." I walked up on the top of Mount Vesuvius, for example, in Naples, Italy, and it you know it erupted in '45 and I had a new pair of shoes and it burned the soles right off the shoes. Now, of course, they have trams that go up in it, but it was an experience. I got locked up in Dansk, Poland; the Russians--they would only allow five to go ashore and we were unloading those horses and I happened to pick five and we drew the straws for it--or lots--and I drew four that were semi-drunks and I was--I was just a young boy. I didn't drink. [Laughs] So we got in this one bar they'd let you go--the Russians would allow one bar and they had two guards in there and this boy had a drink or two, and he said, "You know, I think I can whip that Russian there." I said, "For heaven's sake don't try it." [Laughs] He did; they locked us all up. And the--the Captain of the ship came in the next morning and got us out and we was a sight to see because I wanted to get out of there. [Laughs] I remember it well, so we had a lot of experiences is what I'm really saying. And where Belgium was torn completely up; we were there. London, England...I went to Murmansk, Russia; we carried--the Russians didn't want food or didn't want horses; they wanted weapons. We carried a boat load of anti-aircraft weapons to the Russians. The War was over.

Joyce Newman:

Were they looking at the Chinese or--?

Jack Wallace:

Well now the Chinese, I don't know what--politics wasn't my thing at the time. I really think that they were thinking after World War II of being dominant in the military and they were for a while.

Joyce Newman:

So when you were in the school at Bath were there any particular teachers that you--

that influenced you or--?

Jack Wallace:

No, no.

Joyce Newman:

Or coaches?

Jack Wallace:

We had no coaches; the--our teacher did what coaching. Two of us did our coaching; we just didn't have coaching. But we had--we had a small schedule and--and baseball we probably would play no more than eight, nine, ten games--just wasn't organized, didn't have the resources.

Joyce Newman:

But you played sports following--?

Jack Wallace:

Yes; yes.

Joyce Newman:

So--so when you went to East Carolina you had been in the Merchant Marines?

Jack Wallace:

I had been in the Merchant Marines and came back.

Joyce Newman:

Did you--did anybody go with you the first day of school or did you just go there--?

Jack Wallace:

By myself; yeah.

Joyce Newman:

And how did--and East Carolina was--you knew of because it was in the area?

Jack Wallace:

In the area and we knew--we knew and we had some contact; we roomed in the downtown. We didn't get in the dormitory, but we were downtown with a friend's sister and we stayed there for about three months and we moved. And when they found out that I could hit a baseball, they got me in a dormitory.

Joyce Newman:

Who is we?

Jack Wallace:

Well Jack Boone, Jim Johnson--the coaching, coaching staff; you don't remember those names. Jim Johnson was our first Baseball Coach and he was the Football Coach really, but they had to double up at the time and the second year Jack Boone and that's

where the first scholarship came from. Jack--Coach Boone asked me, he said, "Now are you going to be back next year?" And I said, "Coach, I won't be able to come back because I don't have any money. I'm going to have to go to work." And in a couple days he came back and he said, "If you come back, we're going to pay for everything." And--

Joyce Newman:

So when you said you lived in a house that was all the athletes or--?

Jack Wallace:

No, no. We rented a house--a room really, not a house. It was just a room and we ate in the cafeteria; yeah. I think the--I think the one room that another boy and myself rented--it was $10 a month and we could eat--a whole lot less.

Joyce Newman:

So you lived at first in a house like that and then when they discovered your talent with the baseball then they put you in the dorm with the other athletes or--?

Jack Wallace:

They got me in a dormitory--Slay Dormitory.

Joyce Newman:

And was that where they housed athletes together or--?

Jack Wallace:

Not necessarily; they didn't put them together. They--they were scattered throughout. But if they were an athlete well they were in the dormitory. They--they had what--five, three, four girls dormitories and maybe two boys.

Joyce Newman:

So there weren't--there weren't a lot of--?

Jack Wallace:

Not a lot of dormitory space; right not a lot.

Joyce Newman:

And so you came and your Major was?

Jack Wallace:

Physical Education, Social Studies and Physical Science.

Joyce Newman:

Hmm; that's a lot. [Laughs]

Jack Wallace:

It really wasn't bad.

Joyce Newman:

And so were you--did you prepare to be a teacher there?

Jack Wallace:

That was my goal--to teach and coach; that was what I was shooting for.

Joyce Newman:

And how was it? Do you think having been in the Merchant Marines and traveling made it easier--?

Jack Wallace:

That made it easier--much easier, and you could see--what I could see from the Merchant Marine is you've got to have a college education to get up there. I could see it all over the world and hear it and I knew that that's what I had to do.

Joyce Newman:

But you didn't have any problems adjusting to being in college?

Jack Wallace:

None at all. None at all; no and--.

Joyce Newman:

And then you're away from home.

Jack Wallace:

In fact--in fact, I went out for the football team my first year and I made the team but I didn't play; I was just on the team. And I went out for the basketball--trying to get a scholarship is what I was trying to do and made the team and didn't play. But when it came to baseball as the season started and I started whopping it out in the field real hard they said, "Yeah!" [Laughs] I'm not bragging. I'm just telling you how it was--what we could do. We--we graduated in '51 and I signed with the Chicago Cubs to play that summer and they gave me $3,000 to sign. That's the equivalent to about $250,000 today and geez, I had never had $10 and $3,000 was a lot of money. [Laughs] And I played in AAA ball that summer and had an AAA contract for the next year and came home on Saturday and I was drafted in the Army on Thursday of the next week. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

[Laughs]And this was the Korean War?

Jack Wallace:

It was the Korean War.

Joyce Newman:

And how long were you in the Army?

Jack Wallace:

Two years--you were drafted for two years and I was in there for two years.

Joyce Newman:

What was that like?

Jack Wallace:

Well I'd rather talk--talk with you about those two years than my 45 years teaching. I was a Korean War veteran. I had a college degree and I went into Korea as a private and in two months I was a master sergeant and tried to give--they tried to give me a battlefield commission and I didn't want it because I had a college degree, see. And most of the Korean veterans were inner-city boys and farm boys--dropouts. Rarely did you find one that graduated from college and very few from high school. See the regular Army from World War II had been discharged and they had to have these boys but I was on the front for 16 months.

Joyce Newman:

Good grief.

Jack Wallace:

Lost 157 boys out of my Company. Nobody really cares I don't think; I do--I don't want to say that. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

And it didn't get the publicity that--.

Jack Wallace:

No, and I was a mines expert. I put down 150,000 mines; they're all in the DMZ. I've been back twice, too, and showed the South Koreans--well two South Korean and two North Korean Officers the map of where these minefields were. The railroad was going from North Korea to South Korea now; you read about that--carrying the food supplies and I showed them were we put the--we put down the tank mines on those railroad beds. We used the metal to put them on bunkers and but they've opened that; they've opened that railroad and that's where the food is going through. We put mines--tank mines--on there so the Chinese wouldn't

send tanks down behind us; yeah. But that was--that was the experience of a lifetime. You--it never leaves your mind and when--when you--when I was working teaching it didn't--since I retired and sit around sometimes by myself it comes back. It comes back, so when you read about these boys coming out of Iraq and--and it's in their mind; it's there. But if they get the right or good guidance they can get rid of it but they've got to have it. We didn't have to put up with those IEDs that those boys have--those roadside bombs. We--we just didn't have to do that; we put them down ourselves so the Chinese couldn't get to us but we didn't have the ones that they could stay off a half a mile and set them off. I don't know--I don't know what would have happened--but the Chinese were a formidable enemy. It was tough; they would come at you.

Joyce Newman:

So then after you got out of the Army what happened?

Jack Wallace:

That's when I--that's when I started teaching. I signed a contract to teach in Salisbury, North Carolina, and the Principal of Bath knew I was home and she said, "How about helping me a week. I can't find a teacher." I said, "Okay," and I called Salisbury and they said it would be fine; come in a week later. I stayed 45 years in Bath and don't regret a day because I ran into her; yeah. But I taught--I taught there for 15 years and coached and then the Principal that was there and I went in the Principal's office for 30 years.

Joyce Newman:

So you taught Social Studies?

Jack Wallace:

Well I taught anything they had. I came--when I came back and started teaching I went on back to East Carolina and got a Masters degree and--well I got it in all my field plus Principal and Superintendent Certificate.

Joyce Newman:

Hmm; so that was--when was that? That was--?

Jack Wallace:

That was in '50--I mean '40--well I went to East Carolina but I came

out of Korea in '53 and started teaching in Bath in '53, so I started working on my Masters in '54 and '55.

Joyce Newman:

Did you do that like through the mail or--?

Jack Wallace:

No, no, no; no you couldn't do it through the mail then. You had to go. [Chimes Ring] I would go in the summer; yeah--yeah.

Joyce Newman:

So when--when you were in college the first time did you keep close contact with the--with your family in Bath and--?

Jack Wallace:

Yes; oh yes. Yeah; we'd come--I'd come home every weekend to eat good food. [Laughs] Mom would wash our clothes.

Joyce Newman:

Did you have a car or--?

Jack Wallace:

No; you'd go this way. [Gestures]

Joyce Newman:

Oh, hitchhiked.

Jack Wallace:

Didn't have a car; I got a car when the Cubs gave me enough money and I bought one. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

What kind?

Jack Wallace:

A Chevrolet sedan and--and my brother you know I came--I bought it before I came home on Saturday after playing ball that summer and drove that sucker home and got drafted the next week and so I gave it to one of my younger brothers and I still kid him about him paying me for it today. [Laughs] Oh yeah; no we didn't have a car.

Joyce Newman:

So when you came back from Korea did you get the car back?

Jack Wallace:

No, no; I bought a new one, yeah. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

So you started teaching pretty much--?

Jack Wallace:

In 1953 right after I came back.

Joyce Newman:

And you came back and stayed, so--was that--was that a decision--I mean you could have gone anyplace.

Jack Wallace:

Yes; they were hollering for teachers badly and needed them but I was home and I wanted to coach and teach. The first year, if I can remember, I taught a Civics class and maybe two US History classes and a Geography class and coached all sports.

Joyce Newman:

So you were like where you wanted to be?

Jack Wallace:

That's exactly right--where I wanted to be.

June Wallace:

Let me say something here. We got married in--back in '56 and I--I went to college after I was--well I started before we got married and then continued and we were always--we had planned when I finished college we were going to--to move around. Well Jack was coaching and had excellent teams and we would say well this year we've got a good team coming up next year and all this is going on at school so let's--let's wait a year. And--and we did that for several years and then finally we didn't even talk about it anymore; we just stayed.

Joyce Newman:

Well let's go back to--and start with where you grew up and your family and--.

June Wallace:

Mine is not quite as exciting as his. [Laughs] I grew up in the Bath community also. My parents are Jacob Brinn and Lucy Waters Brinn--were--were not college graduates. They were products of the Depression--children of the Depression and to them you just had to go to work. When I was in high school I decided that I wanted to go to college. My Home Economics teacher was a big influence on me, Rachel Swindell and my Social Studies became a big influence on me also. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

So you were a student?

June Wallace:

Oh yes; that would be really bad today but--we handled it very well and we've been married 51 years so it wasn't--it wasn't too bad was it? [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

So you--you were--you grew up in Bath and your father was--was he a farmer?

June Wallace:

My father farmed; he also did carpenter work. My mother was--was a--a stay-at-home mom. I have three sisters--one older, one five years younger than me and then my first year out of college my mom and dad had another girl. So there were four of us girls; I was the first to go to college but my younger sisters followed. Both of them also went to college.

Joyce Newman:

Did they all go to East Carolina?

June Wallace:

Yes; the younger one finished in Greensboro but--but she started at East Carolina.

Jack Wallace:

But she--but she led the way; she was the first one.

June Wallace:

When I was going with my younger--the one next to me, Sue--I would take her up with me on weekends. I wanted her to see, and by the time she got in high school she--she knew that she wanted to go to college also. I do feel like I was a big influence on her going.

Joyce Newman:

Well how do your family feel; did they--were they encouraged or--?

June Wallace:

Oh yeah; very much so.

Joyce Newman:

Was there a feeling like they wanted you to have--?

June Wallace:

Yeah; they--they did. They felt that way. My dad was always so afraid he couldn't pay for it you know but we managed and then when Jack and I got married we took care of it ourselves, so--.

Joyce Newman:

So why did you choose East Carolina?

June Wallace:

I guess because it was close to home and I knew about it. I knew other people who had gone there. It just seemed the right thing to do and I wanted to be a teacher.

Joyce Newman:

So from the first day that you had been there--had you been through the campus before you entered?

June Wallace:

They had a senior day; as seniors we visited and I think that was my first visit to the campus. I don't remember if we went to any ballgames before I went to college or not but I had very little contact there before I started.

Joyce Newman:

So when you went--the day that you went to go to school did your--did your family take you or--?

June Wallace:

Yes; both of them took me, uh-hm.

Joyce Newman:

Sisters--did they go with you?

June Wallace:

The young one probably did; I can't remember for sure. She could have been in school then. I can't remember if she went or not.

Joyce Newman:

And was it hard--I mean you hadn't traveled the world or anything. Was it a hard adjustment for you to leave home and go there or--?

June Wallace:

Not--not so much so--because I had friends who were there and as a freshman you make friends rather quickly. And it really was not--

Jack Wallace:

And she was a smart one.

June Wallace:

--much of an adjustment.

Jack Wallace:

The academic work was--was easy for her.

Joyce Newman:

What was your Major in?

June Wallace:

I started in Home Economics and that was with the influence of my Home Economics teacher but I--I stayed in that one year and I was smart enough to realize that we were going to be in Bath for a while and that this teacher would be there. And if I wanted to--to teach close to home I better change my Major. [Laughs] So I did and I majored in Elementary Education. And then years later I went back and got certified in Library Science and--and got my Masters.

Joyce Newman:

So your--your younger siblings followed you kind of--

June Wallace:

Yes.

Joyce Newman:

--but nobody else in your family went?

Jack Wallace:

No, none at all.

Joyce Newman:

Why do you think?

June Wallace:

And you had nieces and nephews that went and actually one brother went. Leon went for a while.

Jack Wallace:

Just a short while.

June Wallace:

Because he started when I did.

Jack Wallace:

I think it was finances.

June Wallace:

Economics, yeah.

Jack Wallace:

And they were not as good baseball players as I was. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

Oh so they didn't have a--a scholarship.

Jack Wallace:

They didn't have that talent; yeah but they went on to have families.

Joyce Newman:

Oh and so you probably influenced their children.

Jack Wallace:

That's exactly right and we had two girls and they went to college.

June Wallace:

One went to East Carolina and the other one went to UNC Chapel Hill.

Jack Wallace:

And with their children coming along we've already said now you put money away for these children; so the influence started here--here in this family.

June Wallace:

Well it's interesting to hear our girls and their husbands talk. All four of them say they never knew they had a choice in not going to college. They knew when they got out of high school it was expected, so--.

Joyce Newman:

So it really is a--a shift?

Jack Wallace:

That's what it is.

June Wallace:

Yes; yes.

Joyce Newman:

So when did you start dating?

June Wallace:

I was [Laughs] a junior in high school.

Jack Wallace:

You be--you be careful now.

Joyce Newman:

You can tell now. [Laughs]

June Wallace:

Well it's been so long ago now. I was a junior; we--we thought we were being very discreet but [Laughs] everyone knew it. And we married the Christmas after I graduated from high school and married.

Jack Wallace:

She was in college then.

Joyce Newman:

Okay; so the Christmas after--so you had been there a semester--fall semester?

June Wallace:

We were on the--the quarter system so I had finished one quarter and had started the next.

Joyce Newman:

Okay; then did you live in Greenville and would come home on weekends?

June Wallace:

Yes; yes I did.

Joyce Newman:

Uh-huh; in a dorm? Could you--

June Wallace:

In the dorm; uh-hm, uh-hm just in the dorm.

Joyce Newman:

Did you have a car?

June Wallace:

No; no.

Joyce Newman:

How did you get there by bus or--?

June Wallace:

No; there were several students from this area and we would all ride together.

Jack Wallace:

We had a car and I would--

June Wallace:

Jack would take me back but he would be busy on Fridays--

Jack Wallace:

Pick her up.

June Wallace:

--so I would find a way home and then he would take me back.

Joyce Newman:

And where did you live at that point?

June Wallace:

We lived with Jack's sister in Bath.

Jack Wallace:

In Bath.

June Wallace:

Right in Bath.

Joyce Newman:

So you had--

Jack Wallace:

She was--she had one--my oldest sister, the one I told you about that was so talented, she had one daughter and her husband died earlier and she was raising the girl by herself and I guess it was convenient. She wouldn't let me go live with mom and dad; she said you're going to live here.

June Wallace:

That was when he first came back and he started living with her.

Jack Wallace:

And it worked well.

June Wallace:

And she had a cottage on the river here at Bay View and we stayed there most of the time on weekends and then Jack would stay with her during the week.

Jack Wallace:

So we're dealing with family--strong family ties.

Joyce Newman:

So you did this for three and a half more years then?

June Wallace:

I finished college in three years and one semester. And then I started teaching; my first year was in Washington and I taught fourth grade and the next year there was a vacancy in Bath and the Principal asked me to--to take that position.

Joyce Newman:

This is before you were Principal right? [Laughs]

June Wallace:

Yes; he was still coaching and we debated the pros and the cons and I finally decided to take it and the rest is history. It was wonderful.

Jack Wallace:

We had--

June Wallace:

And we had developed through the years--some people say one place all those many years; but the relationships that you developed are just--they last a lifetime and--.

Jack Wallace:

And we taught three generations.

June Wallace:

When we started getting the grandchildren and the great--no, the great-grandchildren we decided it was time to stop. [Laughs]

Jack Wallace:

And today we walk the streets and they'll come across the street to hug you.

Joyce Newman:

You must be about the two best people in the whole community or I would think. Is the school still K-12 or is--?

Jack Wallace:

No, no; it's--

June Wallace:

In--in 1989--

Jack Wallace:

In 1989.

June Wallace:

--our high school consolidated with the Belhaven School and they moved away--. See prior to that we had K-12. The high school was on one side of the road and the elementary school was on the other side, and Jack was Principal of both. But '89 we consolidated and that left K-12--K-8, excuse me at Bath. So we elected to stay at Bath instead of going into the new school because we were so near retirement and we decided that was the thing for us to do.

Jack Wallace:

I was one of the administrators that pushed kindergarten in North Carolina. And I went in as principal in '68 and '69 and kindergarten was just coming so we were--we were in the racket and we pushed and battled--good, good program.

Joyce Newman:

Well when you went to school here did--did your school experience prepare you well for the work that you did at East Carolina?

June Wallace:

Yes, yes.

Jack Wallace:

Yes.

June Wallace:

Yes; it did.

Joyce Newman:

Well that's interesting because some people have said no.

Jack Wallace:

Yes; it did.

June Wallace:

I felt very well prepared. We have--we have an excellent high school and it continued through the years. A large number--percentage of our students, late '50s on went onto college.

Jack Wallace:

We had from--

June Wallace:

I think maybe my generation it was--we started it because there were so many from my class that went onto college and it just seemed to pick up from there.

Jack Wallace:

We pushed--during the 30 years that I was principal here we encouraged and sent as many as 500 children to East Carolina. We had at least 150 student teachers work through us in the 30 years.

Joyce Newman:

So you had a continuing relationship with East Carolina?

Jack Wallace:

Strong relationship--the John Christenbury Award; have you ever heard of that? No; it's a top athlete in the class. We--we--they gave it to me, the only baseball player that ever got it. It usually goes to a coach of swimming or football or--but we were strong at East Carolina and we still are. The Hall of Fame for Athletes there if you know anything about it it's--it's political and finances. Well I didn't never push to go into the Hall of Fame. They sent the materials to me in '85 and I filled it out and sent it back and in two days they sent it back to me and said you're not qualified. So I said fine; that's okay. It don't make any difference. I was always of the opinion that they didn't have anybody on the baseball--even today and they've got an excellent baseball record--carried my bat on the field.

Joyce Newman:

Well the current Chancellor likes baseball. [Laughs]

Jack Wallace:

Does he?

Joyce Newman:

Yeah; so was there any particular teacher that you had at East Carolina who stood out or encouraged or influenced--?

June Wallace:

I think one of my favorite Professors was Dr. Paschal and he was in the Social Studies area.

Jack Wallace:

Social Studies.

June Wallace:

And he was a wonderful, wonderful teacher. He was my--my very favorite one.

Jack Wallace:

Dr. Long was an administrator when I went in and he's the one that interviewed me. He was in the front office and good, good person, good administrator. I had a short-sleeved shirt on and I went in and he said uh-huh; I can tell you're a farmer. [Laughs] I'll always remember it but he was good. You could depend on him. They had some good people over there.

Joyce Newman:

So both of you got--you did your Undergraduate work and then later you--

Jack Wallace:

Masters.

Joyce Newman:

--both went back and did Masters too, so this was all in the--what--it was the School of Education I guess.

Jack Wallace:

That's right.

June Wallace:

Uh-hm.

Jack Wallace:

Yeah.

Joyce Newman:

So it was very important. Did--did you feel like I mean some--someone else I interviewed I talked about the quality of education she got in preparation to be a teacher and she felt like it was way ahead of what other people seemed to get in other colleges--that East Carolina was kind of you know doing things earlier there than other places seemed to have been. Did you feel that?

June Wallace:

I did and I thought in the Education Department your senior year where they really begin preparing you to teach I felt that I had very good instructions.

Jack Wallace:

My Masters degree when I--when I went back in '54--'55--that was some of the best instructors that you could find anywhere. Well they had just put the Masters Program in; I was in one of the first groups that came through. And I had good, good people, strong--as strong as Carolina, State or Duke--any of them and I'll tell you; I've had classes at all of them.

Joyce Newman:

So were you doing your Masters degree while you were still in college or did you finish and--?

June Wallace:

I was in high school.

Joyce Newman:

In high school.

Jack Wallace:

She was what?

June Wallace:

I was still in high school. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

So you did that quickly after you--?

Jack Wallace:

Yeah, after I came back I did.

Joyce Newman:

Yeah, so you did that--you had finished that before you went to college and then later you went back and got your Masters?

June Wallace:

Uh-hm.

Joyce Newman:

So some--some people said that--that you know that going to college separates them from people they knew in high school or their community or even their families but it doesn't sound like you--.

Jack Wallace:

Not in our case at all; uh-um. Of course--

Joyce Newman:

Yeah; either of you.

Jack Wallace:

--we came back home to work. If you could--and I visualized this; if

I had taken a job in Salisbury and had gone on I wouldn't have ever known here.

June Wallace:

And I don't think your ties would have been--you probably would have moved--moved up on--.

Jack Wallace:

You see I didn't ever teach in any other school except right here and your ties were close--close.

Joyce Newman:

Do you think that--did you already have that kind of--I mean you mentioned the closeness of the family and the closeness of--was the same way with the community. You came back and contributed so strongly to the community for a long time.

Jack Wallace:

My--my philosophy was and still is that the children in this community had the right to have as good of an education as any student anywhere else. That was my philosophy and I pushed that--pushed it hard.

Joyce Newman:

Is there a relationship between playing sports and being part of a team and your field about education and the service?

Jack Wallace:

Yes; it is--yes. The--the boys that went through our program in athletics at Bath high school they had to do well in the classroom before they could go with me and they knew it. And I--I can't remember any boys dropping out of school; they graduated.

Joyce Newman:

So you made--you sort of addressed both--both aspects?

Jack Wallace:

The same way--the same way.

Joyce Newman:

Did you have other people who went and played sports at ECU?

Jack Wallace:

We had--we had a couple of boys to go and play. We had one to go--several; I can't name them because I can't--but yes, we had some; not that many--not that many. Some went to State College and played.

June Wallace:

Carolina.

Jack Wallace:

Carolina and played, so we--we had--

June Wallace:

Some of the smaller schools.

Jack Wallace:

--on scholarship most of them because you'd have some pretty good ones to come through a rural area, but academics was both--both of us pushed it hard. And when the schools consolidated in '89 and '90 from a K-12 school to a K-8 school I dickered around whether to go with the high school or stay here and I decided to stay and that was a good move, so we pushed. And when we--I'm blowing my horn I guess but when we left or retired this school ranked 15th in the State of North Carolina academically.

Joyce Newman:

Quite an achievement.

Jack Wallace:

And now I'm telling you--and it's still good today--still good; this is a strong community and we had--we had a hand in it.

Joyce Newman:

Is it making a difference--are a lot of people moving into this town?

Jack Wallace:

Yes; they are now.

June Wallace:

But a good number of retirees are moving--moving in.

Jack Wallace:

We're getting a lot of--lot of retirees out of the northeast which don't have children in school. The children in school here are the people that grew up here.

June Wallace:

But we still have families moving in to get their children in Bath.

Joyce Newman:

Oh because it's so good?

June Wallace:

And that's been going on--in Bath schools, so--.

Jack Wallace:

The one thing they always complain--you don't have enough housing here.

Joyce Newman:

[Laughs]So your pull--you're actually--?

Jack Wallace:

Pulling people.

Joyce Newman:

You're pulling people into your school so--so you're having then what's not just in your local community but you're--you're you know--so ECU through you is you know--is--is still having--is reaching out and pulling people in--?

Jack Wallace:

That's exactly right.

Joyce Newman:

That's very interesting.

Jack Wallace:

One--one interesting tidbit that I didn't tell you about that I--I like to--I tell myself that. My playing athletics at East Carolina and signing with the Pros, when I went into Korea I could move; I came home in my mind because of the training that I got at East Carolina University physically and mentally.

Joyce Newman:

Uh-hm.

Jack Wallace:

Yeah; I was able to come home.

Joyce Newman:

Interesting and--and you also--you were already--I mean you became a principal but you had already in the Army--you had already very quickly moved into leadership roles.

Jack Wallace:

Leadership, yeah.

Joyce Newman:

Yeah; was that related to the sports at all or to--?

Jack Wallace:

Well I--I guess it started of course because I was a college graduate and--and we didn't have leaders. And here I was and--and I accepted it and went with it, and yes; it did--it gave you an incentive--

June Wallace:

He's always been a good leader. He really has.

Jack Wallace:

--to be--.

Joyce Newman:

Well and I know because I read your email; you should say the awards you won in the Army, the--the different--.

Jack Wallace:

Yeah; they--they--and boys that I had were just as--just as competent when we were together.

Joyce Newman:

But you got--you got the--?

Jack Wallace:

I had a Silver Star and Bronze Star, Greek Gold Leaf, South Korean Medal of Honor, seven major battles. I love to talk about it; people don't know.

Joyce Newman:

Well we should do another interview about that. [Laughs]

June Wallace:

We had that wonderful experience--I forget the year; the early '90s when the Korean War Memorial was dedicated in Washington, DC. We went to that and it was quite a moving--moving and wonderful experience to be a part of that.

Joyce Newman:

Well you know there's this recent thing about doing interviews and--and recording stories of World War II veterans but nobody is doing that for the Korean War.

Jack Wallace:

No, never have; see the Korean War wasn't one anybody wanted. We--World War II was just over and people were trying to regain their lives and here the North Koreans and they decided we had a contingent of people over there that were--most of your vets--World War II veterans were out and you just had those draftees in there and they kicked the tar out of everybody until we finally got enough people in there.

Joyce Newman:

But anyway they make movies about the Korean War but--.

Jack Wallace:

I think they maybe had two--not many, not many.

June Wallace:

There were some.

Jack Wallace:

Not many at all.

Joyce Newman:

Not like they do though of World War II.

Jack Wallace:

That's true. I occasionally--I won't do much of it now--will go to a club, Rotary Club and speak about it you know. The last one--kind of confine it; you know because when talk about minefields people don't know what you're talking about. You've heard of mines and Elizabeth or--not--what's her name, the British lady that was trying to do away with mines?

June Wallace:

Princess Diana.

Jack Wallace:

Princess Di, she--she would have thought I was a monster.

Joyce Newman:

Putting them down?

Jack Wallace:

Putting them down and taking them up but--and then in our estimation we probably saved as many as 10,000 lives because the Chinese couldn't get to us unless they came through those minefields. And I tell myself this anyway. But they're still there; they will stay--copper--copper fuses and cast iron, it will stay 100 years. Yeah; when they take that DMZ down they've got a big job on their hands. We were in the [Kumhwa] Valley and the [Chorwon] Valley which is the corridor that goes directly up from Seoul into [P'yongyang] see--trains rode and the DMZ just blocks it off and it's full of mines. [Laughs] Somebody has got to take them up. But it's--it's--it's interesting to me anyway. We're working on a little project now that I hadn't intended to work on but we are through the Defense Department in Washington, D.C., and Walter Jones is helping me with it.

Joyce Newman:

What is it to do?

Jack Wallace:

Well you ought not to ask that. [Laughs] The last part of the War if you know anything about the Korean War, it loops up above the 38th Parallel and the 38th is the

dividing line between North and South, and they wanted to push that line down and they broke through the South Korean line and we were at--we were--we were setting here and the South Korean Division was here and they ran. Well the Chinese just flooded through. Well we were in blocking position, my--my platoon and they--they would mutilate American bodies once they killed them with bayonets. We came out with just seven of our boys and on the backside of the fighting line trenches they dug a--you could go in there at the mountain head and just dig a hole in here and that was called a sleeping bunker. So we moved these seven boys in there and I did it with my platoon, maybe three minutes, and I said boys we've got to cover them up so the Chinese can't find them. We did; we didn't have time to get dog tags and they're still there. So I was thinking they'd take that fence down a number of years ago and I talked with the South Koreans. I went back in '82 and '89 and they were not interested. They--polite you know and I said well when they take this fence down I'll be back and [Chimes Ring]--and I'll show them where they are. The dog tags are still there; the bodies are not. But I decided I was getting too old and they're not going to take that fence down any time. So I told Walter let--let me identify them and so he got the State Defense Department and we've been in contact, so I know exactly where they are if I could get the right maps and that's what I can't get, so--to--to pinpoint them. We were on a hill called Boomerang and the Americans named these hills--Bloody Ridge or Boomerang, Harry, White Horse--but this was Boomerang and if I could get the map. We--he gave me the coordinates, the Defense Department gave me the coordinates but we couldn't pull it up on our computer, so the--the boy that I'm working with, I believe he was from California and he'll be back in next week, so I'm going to see if I can get him to find me an overlay and then I'll identify it and they'll put it on file and when they bring the fence down they can find those boys--

because I know there's seven families somewhere. There's more than that, but I know there's seven families somewhere that would like to know where their sons--.

Joyce Newman:

Well what is--I've heard of it but I've never gone--the computer thing that you know where they have the views of the earth and the--?

June Wallace:

The Google.

Jack Wallace:

Google Satellite.

June Wallace:

Google Earth I think.

Jack Wallace:

Satellite it's amazing and we--he gave me the coordinates so we can look at that but we can bring it up and I can find it but I can't identify it. It's not clear enough. And we--I don't know whether we're doing everything right or not. I've got a fellow up at the community college I think I'm going to next week after Memorial Day. I'm on the Board of Trustees at the community college and he's an expert and I'm going to try to see what he can do with it.

Joyce Newman:

I wonder if any like the Geography people at East Carolina would be helpful.

June Wallace:

They might.

Jack Wallace:

They might; they could. But if I can get--if I could get a good overlay I could identify where this cave is or come close to it and it could be found once they take that fence down. So that's just a project I'm doing.

Joyce Newman:

Still serving the community.

Jack Wallace:

Well it's serving me more than anybody else.

Joyce Newman:

So tell me what the Christenbury Award--.

Jack Wallace:

The Christenbury Award, they give--John Christenbury was a

coach in the '40s--'41, '42, '43, '44 and he got killed.

June Wallace:

In the service.

Jack Wallace:

In the service, so they named--he was--he was a coach at East Carolina and they named the Christenbury Award and they give it annually to one person in each class. So they gave it to me in '51--the only baseball player that's ever gotten it. [Laughs] I think--you don't remember Dr. ["Peppy" Toll], Sociology? What was the Math Teacher that we liked so much--? Anyway it's selected by the faculty and not coaches; the faculty selects this. Well they--they never had given it to a baseball fan but all these--Dr. Toll was Sociology and I--I can't say that I ever saw him down at a baseball game but he--.

June Wallace:

I can't think of it.

Jack Wallace:

Huh? But he knew baseball and I guess he said that's the boy who is going to get it. Oh this other fellow that taught Math; if I could get his name. Well you might not know him but he was a good Math Teacher and taught--I had Algebra under him I believe but he wanted to come down and coach some and help Jack Boone. And Jack said all right; he--he worked with Wallace over there. So he was going to show me some things and I said fine. I knew--I was taking Algebra and I said yes, sir; come on. And the next game I remember it well--the next game after the first week he was there with me I think I went five for five or something like that. And I got in class the next day and he said I want all of you to know this boy got five or five and I was the cause of it. [Laughs] That was okay with me; I had an A in that class. Oh me--oh what was his name? He was just--

June Wallace:

I can--I can see his face but I can't think--.

Jack Wallace:

He was a good fellow. If you haven't been there but eight years you

wouldn't know him but he was--he was an excellent teacher. They--they--as you said they had some good faculty at East Carolina and I'm sure they still have.

Joyce Newman:

How many people were there--students when you were there?

Jack Wallace:

Oh let's see; the GIs were coming back in '48--I mean '47 when I started. They opened it up and I want to say in the 2,000 to 3,000 range at the time.

Joyce Newman:

Boy it's really grown.

Jack Wallace:

Oh it's grown.

June Wallace:

Uh-hm.

Jack Wallace:

Before we graduated it was--shew--.

Joyce Newman:

So once--once you were in college then you started coming down on weekends and going to sports things?

Jack Wallace:

You mean over--over at East Carolina? Yes, yeah.

Joyce Newman:

Not on Friday nights because you were here?

Jack Wallace:

Yeah, we were coaching here but we'd go on the weekends for football especially. You have never interviewed a couple like us. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

So--so this--so you going to college was not a traumatic experience in any way?

Jack Wallace:

No, it was a joy.

Joyce Newman:

It was a joy?

Jack Wallace:

Yeah, a joy.

Joyce Newman:

And you studied Education the rest of the time until you retired?

June Wallace:

Jack retired after 45 years and I had 36. [Laughs]

Jack Wallace:

And we made a contribution in this community which we wanted to--

we wanted to do and got the opportunity to do it, so--. It--it's rewarding.

Joyce Newman:

Well is there anything else you want to tell me about--about--?

Jack Wallace:

No, we have two daughters. Did I tell you that?

June Wallace:

Yes, you did.

Jack Wallace:

And we have four grandchildren and we have two girls, two grandchildren in South Carolina--Charleston--and we have one daughter, granddaughter and one grandson in Goldsboro.

June Wallace:

And she's a teacher. That daughter is a teacher.

Jack Wallace:

And she's a teacher, so we're--.

June Wallace:

But life is good. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

Well it sounds like you're in the perfect place for you to be--both of you and--and with each other. That's really good.

June Wallace:

We think so.

Joyce Newman:

So what do you think made both of you--what was it in your childhood that--that made the change in your lives possible for you? Was it your family, the values they taught you; was it the community or--?

June Wallace:

I think it was a combination. Family values and--and the community--community was strong and I knew if I didn't do something right my mom would know it before I got home. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

So--so you never really left the network to--to--even though you were away at school you were still within the network of the community and the family?

June Wallace:

Uh-hm.

Jack Wallace:

I always had a strong desire to win, to do well, and with a family of 10 you just had to push. And we worked and dad must--we worked sunup until sundown and that made you stronger.

June Wallace:

I think growing up--right; I started to say growing up like we did we learned the value of work. And I've--I've thought about that a lot recently and I'm so thankful that my mom and dad taught me the importance of doing a good job in anything that you did. You did the best that you could. And I think that stayed--

Jack Wallace:

For 30 years--

June Wallace:

--all through our career.

Jack Wallace:

--yeah, for 30 years and as the administrator or principal at school I was--I was there at 6 o'clock in the morning and I would start the air-conditioning or the heat and I wouldn't let the janitor come in until 8 o'clock because I needed him in the afternoon to work eight hours. So I would leave there at 5:00--5:30 and--.

Joyce Newman:

That's a long day isn't it?

Jack Wallace:

Long days.

Joyce Newman:

But this--this is like you said you hit the ball--liked to hit it hard.

Jack Wallace:

That's right and you want--you--you had to do; you had to go. I was thankful to be there--be there to work and being able to work. Health has always been good for both of us; June's a nine-year--?

June Wallace:

Ten.

Jack Wallace:

Cancer survivor and--and we--we just pushed. I'm trying to slow down and she won't let me. [Laughs] I want to slow down but it's...October 27th I was 80 years-old

and--.

June Wallace:

And it's the first time he's ever admitted that he's getting older. [Laughs]

Jack Wallace:

And normally I would never do that. But we've had a good life; health is good.

Joyce Newman:

I don't think either of you looks your age. [Laughs]

Jack Wallace:

I didn't see you flinch when I told you that. [Laughs] I was looking for you to flinch, but our health is good. My mom lived to be 100 and I hope I have some of her good genes. Now I've had brothers that didn't reach the age there and sisters that passed away. So--so we've had a good life and--and we're going to leave Friday morning camping this weekend.

Joyce Newman:

Where to?

Jack Wallace:

We go down to the Emerald Isle. We camped when the girls were growing up; we--we'd camp all the time in the summer and for 25--30 years we didn't camp any. So last summer my two girls and the grandchildren and this one said we've got to go camping again so we got to go. I'm not enthused about it but I--I go. [Laughs]

Joyce Newman:

What--what is it that you're not enthusiastic about?

Jack Wallace:

Well I--I tell them that I'm passed the camping age. [Laughs] But with the grandchildren there and June, why it's okay; we can handle it. We've been married for 51--well we told you--51 years. We haven't had--ever had many fights--very, very few.

Joyce Newman:

Well now you both look so happy. [Laughs]

Jack Wallace:

And I help her wash the dishes and I can--I can do a

little--I can do a little cooking. But East Carolina was our backbone; it was our backbone.

June Wallace:

Well it made our lives as we've known it possible.

Jack Wallace:

And I guess if--if I would have any frown it would be this Hall of Fame I mentioned to you. I should have been in there--no question. They--my--you don't know anything about statistics in baseball do you?

Joyce Newman:

Uh-um but someone else might if you want--. [Laughs]

Jack Wallace:

Well I ought not to put it on there, but my junior year I hit 483 and had 13 homeruns and my senior year I hit 487 and had 17 homeruns and that's unheard of. Now the first thing a Coach today would say--well you didn't have any pitching you were hitting against. But we had just as good a pitching then as they have now.

Joyce Newman:

So no wonder they gave you a scholarship for baseball. [Laughs]

June Wallace:

[Dog Barking]Excuse me a minute.

Jack Wallace:

Well the--the--the thing is we didn't have as many see and our record was not great. In fact we had two hitters on the team that could get on and Jack Boone, the Coach he'd shuffle me around and try to get me to--behind one that might get on base and I'd knock them in, so we'd win. But it was--it was good years; it was good years.

Joyce Newman:

So what--what is your most vivid memory of something that happened while you were at East Carolina?

Jack Wallace:

East Carolina--I have a lot of them I could tell you but one that's--that was a lot of--lot of good memory, but there used to be between Atlantic Christian College which is now Barton College; they were on our schedule and they had what they'd call the Old Oaken Bucket. If they won a game it went to them and if we won a game it would come to us.

And we would keep the bucket. [Laughs] And we were playing baseball and they had the bucket and they brought it. You had to bring it with you when they came; they just did that with East Carolina and Barton and I don't know how it started. But they brought the bucket down that day and--and [Laughs] we whipped them and Coach Boone said, you know, "Wallace," he said, "you go over there and get the bucket." And the game was just over. So I go over to get the bucket and they wouldn't let me have it. And they had one boy that had--was on a pair of crutches. And I can remember it well [Laughs]; he had one crutch is what he had, an old aluminum crutch and he said, "You touch that bucket you're going to feel this." [Laughs] So I pick up the bucket and he swings that sucker. Well I caught it [Laughs]; I caught his--his crutch and [Voom] we whipped him on the ground. Well by that time see we had our team and their team and I remember it well. [Laughs] But we got the bucket. And we carried it back over to our side. That's just one but it was a lot of good--good things.

One--I can't tell you her first name--Miss Rose taught U.S. History and she was a good one, but she couldn't hear. She had a hearing aid and you could lift your feet off the floor and she couldn't hear it. [Laughs] So--so the boys would--if she was giving a test and they'd say Wallace, lift your feet off the floor; I want to ask you something. So I'd lift my feet off the floor and they'd ask and now "What's the answer to number five?" [Laughs] I remember Miss Rose well and she was a good teacher and I--I remember my thoughts--well they ought not be taking advantage of this lady like this--as good a teacher as she was; yeah. And we had some good people. What was that little short History Professor, hmm?

June Wallace:

I was going to say Todd but--.

Jack Wallace:

No, it wasn't Todd--Dr. Coleman?

June Wallace:

Coleman--Coleman.

Jack Wallace:

Coleman, no he wasn't short.

June Wallace:

Yes; he was.

Jack Wallace:

Was he? Okay, it was Dr. Coleman and he was just a short fellow, I'm going to save five-three, five-four, but a good teacher and he always sat on the desk and his feet would hang down about halfway to the floor and he'd do all of his lecturing sitting on that desk. And when class was over he'd jump down and that was it; but he was a good--good instructor, very, very good. So you asked a few minutes ago whether they've had some good instructors--I'm sure they still have them but they had some good instructors from the '40s on. And they just had them; they were there.

Joyce Newman:

So the--the Oaken Bucket leads into your story about the hurricane and the damage to your house? [Laughs]

Jack Wallace:

[Laughs]It might, yeah.

Joyce Newman:

So do you want to tell that for the record?

Jack Wallace:

That old Oaken Bucket--gosh; that tree that came in the house--this chair right here, this leather chair was sitting over here and the TV was in that corner. And I always sat in that chair. And when that--if I had been sitting in that chair when that tree came in--it hit--

June Wallace:

A beam fell across the chair.

Jack Wallace:

Across the chair, so you never know; we say well fate--you're still surviving. I can hear the boys in Korea when they started shelling. Where is Wallace? Where is Wallace? Well Wallace was over there under a rock. I can hear them now--inner city and farm

boys; if you had any prestige or your parents had any prestige at all you got a deferment. And we didn't have any.

Joyce Newman:

Well I was wondering before if there was deferments like there were in the--?

Jack Wallace:

Yeah; you could--you could get a deferment to go--. Now I was--when--when I finished teaching--I mean playing ball that summer I was going to coach up in the--in the western part of the State. I was going to take a job; in fact I had taken the job and signed the contract. And I called my Draft Board to transfer my records to Salisbury--no; it wasn't Salisbury. What was it? Anyway--anyway it was in the western part of the State and they said we can't transfer your records. They said your records are here and you need to come home and--because you're going to be drafted. [Laughs] It was done; they wouldn't transfer them so I couldn't--if--if I had started teaching and had been teaching I could have got a deferment, but I was--I was free. And they--they needed--they needed bodies over there at the time.

You see in that Korean War we lost 54,000 men during the War. What? I know I did--I know I did and the Vietnam War is 57,000 killed. And 4,000 in Iraq is too many; the Korean War was three years and Iraq we've been there five. I'm not opposed to the Iraqi War at all. A lot of people are and that's okay. But the Korean War was--nobody cared.

Joyce Newman:

Well is there anything else you want to say for the--?

Jack Wallace:

No, I've talked--I've talked too much.

Joyce Newman:

Oh no not at all; that's great.

[End Jack and June Wallace Interview]