| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

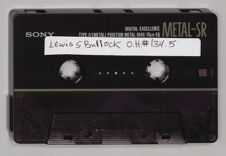

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #134 | |

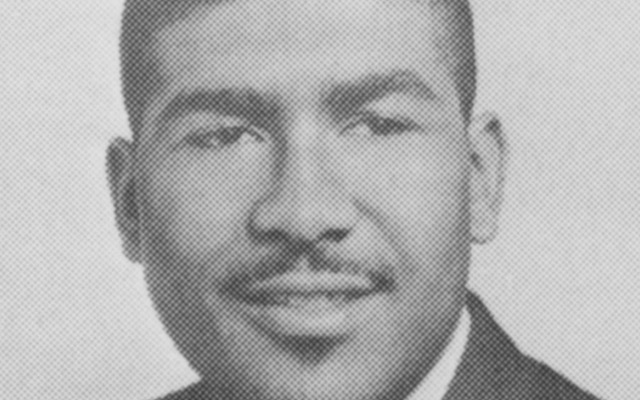

| Lewis S. Bullock | |

| Eastern Carolina Symphonic Choir | |

| April 10, 1992 | |

| (Mrs. Margaret Bullock, Lewis Bullock's wife, also participated in this oral history interview.) |

Donald R. Lennon:

What I would like for us to do for a little while this morning is to just go back and look at your career. If you will start off with a little bit about your background before you arrived in North Carolina, where you grew up, your educational background, and what led you into a career in choral music.

(Conversation)Lewis S. Bullock:

I was born in Detroit, Michigan, eighty-one years ago. My father was a baptist minister. I went to Western State Teachers College in Kalamazoo for a year. My sister lived in Rochester, NY, because her husband was going to the divinity school in Rochester, NY. I decided that I would go and spend a little time with my sister. There I heard the Westminster Choir sing at one of the churches in NY and I was fascinated with the quality of the chorus. I decided at that time that I would like to go to Westminster Choir College and I did. The school was then in Ithaca, NY, combined with the Ithaca College. I was there for a year until the choir college moved to Princeton, NJ.

Margaret Bullock:

He grew up in Kalamazoo.

Lewis S. Bullock:

I grew up in Kalamazoo, Michigan, the “celery city” of Michigan. Some interesting things happened then. During my senior year, the Westminster Choir made a trip to Europe in 1934. We visited fourteen European countries including Soviet Russia. We were the first American group to enter Soviet Russia, after we [the United States] recognized Russia in 1934. We gave five concerts in Leningrad and seven in Moscow. The trip was quite a fascinating adventure.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was Leningrad and Moscow like in 1934?

Lewis S. Bullock:

It looked like they were building all the time, but it didn't look like the buildings were going to last very long. We were quite curious, because everything looked really drab. One interesting aspect was that we were not allowed to go anywhere, except if someone was along with us. When I took a picture with my camera at the airport, authorities grabbed my camera and took the film out of it. One time three of us fellows had a day off and we decided we would like to do something different. One of the fellows who was on the tour with us as a tour guide said: "Let's go see a commune, one of the Russian prisons." We weren't supposed to do that, but we got on a train and went out to this commune. It happened to be a shoe factory. I don't know why, but the fellow there asked the three of us what our fathers did. One of the fellows said his father was a doctor. I don't remember what the other one fellow said. My father was a minister. In Soviet Russia I didn't want to say he was a minister, so since it was a shoe factory we were visiting, I told the man he was a mender of souls. I thought I'd get by with that.

Donald R. Lennon:

. . . the language barrier. Were they speaking English or was there someone with

you that could speak Russian?

Lewis S. Bullock:

Well, one of us could speak Russian--he was the interpreter. He went along as a tour guide for me and my three friends. It was quite an interesting experience.

Margaret Bullock:

Tell him about the people at the concerts and what happened at them.

Lewis S. Bullock:

There was an interesting concert in Moscow. People lined the streets from the concert hall to the hotel on both sides and we marched through like a triumphful exit. Everyone was so enthusiastic about what they had seen. We then returned home. It was my senior year, and the choir was going to make a tour -- they were going to Akron, Ohio, where my parents, were living. One noon, Dr. Williamson, the president of the college, came up to my table where I was having lunch and said, "I would like to see you, if you are not too interested in dessert." I said, "What have I done now?" Well, when I went there, they [the school] had established in North Carolina a special music project with various graduates of the college. One of the members, who had an area around Goldsboro, left for a big church in Texas and they needed somebody to replace him. This representative of the group was there with Dr. Williamson. Dr. Williamson said, "If you will go down and take this job, we will give you credit for your senior year." I thought that was a pretty good deal. I left.

Margaret Bullock:

You had to go back to do an Auburn recital.

Donald R. Lennon:

The purpose of you accepting the job was to work with these community choruses. Was that an outreach of the church or was it something that Westminster had set up independently of the church?

Lewis S. Bullock:

A fellow named Mr. Alderman, here in eastern [North] Carolina, had the idea of

having a statewide music project. He had contacted Westminster Choir College to get men to. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this the educator Edwin Alderman?

Margaret Bullock:

No, his name was Pat Alderman.

Lewis S. Bullock:

The idea was that each man would have five units. He would have a church on the weekends and then four different cities, like Kinston, Goldsboro in his area. We usually would have a rehearsal one night and high school choruses and so on. I could have gone back to graduate, but I would have had to set up an organ and voice recital in June of 1945. When I arrived in Goldsboro, I thought I had arrived at the end of the world in the little station I arrived in. A. J. Smith was pastor of the First Baptist Church I was going to have in Goldsboro and I stayed at his home. He took me in almost like a son and that made me feel a little better. I remember at the end of that first year, all the choruses combined with these five representatives which extended through the eastern part of North Carolina.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was financing this? Did Westminster pay for it?

Lewis S. Bullock:

No. Each unit, like the church, had five hundred dollars. Each member of the Goldsboro Community Chorus paid five dollars a year to join the chorus. Even in the schools where they had no credit back in that time, in the junior high school choirs and the high schools they paid a small fee to join the chorus.

Donald R. Lennon:

So your salary came from different sources? And if your choirs weren't successful . . . .

Lewis S. Bullock:

Yes. I think it was eighteen hundred dollars a year.

Margaret Bullock:

I think one year we made eighteen hundred dollars for the year.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Combined salary.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was right in the middle of the Depression, in the mid-thirties.

Margaret Bullock:

That was 1936 or 1937. There would always be one outstanding person in each town who--if we didn't have any money for that--would be responsible for going out and raising the money locally to keep that chorus going.

Donald R. Lennon:

What towns other than Goldsboro and Kinston did you work in initially?

Lewis S. Bullock:

I didn't have Kinston at that time. I originally had Goldsboro, Mt. Olive, Farmville, and Newton Grove.

Margaret Bullock:

Wilson. You didn't go to Wilson.

Lewis S. Bullock:

A high school in Hookerton, Winterville and Greenville, NC.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had quite a bit of traveling to do to go from school to school.

Lewis S. Bullock:

It was singing in a different chorus each night and that then, during the day, there would be the high school and junior high school choruses. We sure did. Besides that, I had about thirty private voice pupils sandwiched in to help with expenses. At the end of that first year, we had a big combined festival in the stadium in Raleigh. Dr. Winston (?) came down from the choir college and each leader of his various units would conduct a number for the festival. I remember a freight train came along and made so much noise it interrupted the festival.

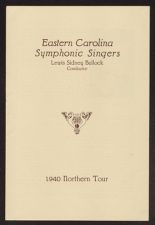

After that things sort of disintegrated a little bit as the members of the other units faded out. My groups wanted to stay together, so I organized my own group as the Eastern Carolina Symphonic Choral Association.

Donald R. Lennon:

After that first year, your group was the only one that continued to function?

Lewis S. Bullock:

The only one. We stayed together.

Donald R. Lennon:

When did you and Mrs. Bullock get together?

Lewis S. Bullock:

That is an interesting story, too. We had an operetta called "The Ghost of Lollipop Bay." We thought some of the smaller schools in the area . . . would be interesting to help them put on an operetta. So we went to some of the very small schools. One of them happened to be Fremont. In Fremont, there was a young lady, a beautiful young lady with beautiful black hair, who also had the glee club. She helped with putting on the "Ghost of Lollipop Bay." I sort of took a fancy to this girl and started giving her voice lessons and then she moved to Goldsboro to teach in the Goldsboro High school, where I had my headquarters. I guess she decided that if she married me she wouldn't have to pay for those voice lessons.

Margaret Bullock:

That is an awfully good story, but it is not true.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We married June 3, 1936.

Margaret Bullock:

We went together a year.

Lewis S. Bullock:

She was very instrumental. She would accompany on the piano with some of the junior high school groups that I had. Each year the Eastern Carolina Symphonic Choral Association would give a festival. Many times we took the group back to Princeton for their Talbot Festival. They had a big festival each year around commencement time.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you would, even at a fairly early period, go out of state then?

Lewis S. Bullock:

Well, we just took members of the group just to visit at that time.

Margaret Bullock:

The adults mostly just went to those.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were not performing.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Each year in Greensboro, they would have the music contest and I took my groups. They all had these beautiful maroon vestments. They almost looked like the Westminster Choir. I always had that in my mind--the Westminster Choir had the beautiful vestments. We always did very well at these [contests] in Greensboro.

Donald R. Lennon:

If the choruses died out except for your groups after that first year, who were you competing against in Greensboro?

Lewis S. Bullock:

That was the state. You were graded. We weren't actually competing.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there other community choruses?

Lewis S. Bullock:

From all over the state.

Margaret Bullock:

These were high school.

Lewis S. Bullock:

You were graded number one or number two and you would have a soprano soloist and a bass soloist and a girls glee club and then they had some major judge that would grade them. It was an annual affair in Greensboro. Choruses from all over the state.

Margaret Bullock:

You must tell him the experience with Malcolm in the contest.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Most of the members from these schools were from small class C schools. Many of them were from tenant farms who never been a few miles from home. One boy named Malcolm, he was a little older than most of them, had a big deep bass voice. He couldn't stay on pitch. I would place him next to two of the other basses to try to keep him in line. He wanted to sing a solo at the contest. I told him, “Alright.” Well he started and he got way off the track and the judge afterwards said to me, "What in the world did you let this fellow . . . why did you have him?" I said, "Well, experience is good for him. He will be alright." That was his first year. I remember the last year he sang and got a number one--a

superior rating.

Margaret Bullock:

That was Malcolm.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Malcolm, was just here the other day.

I had a dream that we were giving a concert at the White House. I thought I would select an unusual group from four high schools in Winterville, Ayden, and Snow Hill, which was one of the cities where we had a civic chorus.

Margaret Bullock:

Farmville.

Lewis S. Bullock:

I selected the best ones--twenty boys and twenty girls. I said that they'll have to practice on their weekends--that was the only time. We would have a certain area and we would meet at about two o'clock in the afternoon and rehearse for about six hours. They couldn't read music so we would play one section at a time and they would memorize the whole program. They memorized a very stiff program. The interesting thing was, about three or four months after I had that dream, we were giving a concert at the White House. Mrs. Roosevelt invited us. It was a reception, given in honor of the wives of the congressmen, in the Rose Garden. The Marine band also played incidental music.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did Mrs. Roosevelt come to invite you?

Lewis S. Bullock:

Well, I wrote a letter saying that we would like to come.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this after the dream?

Lewis S. Bullock:

After the dream, and after we rehearsed. We sang in various cities nearby with a group and I got an answer back that everything had been filled and “sorry.”

Margaret Bullock:

Mrs. Mark Lassiter.

Lewis S. Bullock:

I remember Mrs. Mark Lassiter and. . . .

Margaret Bullock:

Mr. Lassiter was on the board of the University of North Carolina.

Donald R. Lennon:

I knew Mrs. Lassiter.

Margaret Bullock:

You knew Mrs. Mark Lassiter.

Donald R. Lennon:

In Snow Hill.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Who was the Senator?

Margaret Bullock:

Senator Kerr. I believed he called himself Kerr [pronounced like “car”]. But Mrs. Lassiter was really one of the most important people in this whole outfit that kept everything going. Whenever there was a lull anywhere, she stepped in. There were about four or five different parents, who no matter what, they came to our rescue. Mrs. Lassiter paid Malcolm's way to California. Malcolm did not have the money to go.

Donald R. Lennon:

It seemed like he shared that with me over at his house one day.

Margaret Bullock:

Oh, he did. He is the most remarkable somebody I've ever known.

Lewis S. Bullock:

They got in contact with Mrs. Roosevelt.

Donald R. Lennon:

John Kerr had a lot of clout anyway.

Margaret Bullock:

And John Kerr knew Mark Lassiter. Through Mrs. Lassiter, she reached him and he reached the White House.

Lewis S. Bullock:

They had these vestments. It was warm and it was in the summer time and they had these long vestments on. So the boys took their pants off during the concert. One of the fellows after it said: "How did you enjoy singing for Mrs. Roosevelt?" I think it was Malcolm.

Margaret Bullock:

It was Malcolm.

Lewis S. Bullock:

He said, "I enjoyed it but I never thought I was going to meet her with my pants off."

Another interesting thing was when we went in [the White House], they took the cameras away from everybody. Everyone was disappointed because they couldn't take any pictures. Mrs. Roosevelt said, "What do you mean?"

Margaret Bullock:

Malcolm was the one who did that [told her].

Lewis S. Bullock:

She went up [to the guards] and told them to give the cameras back and let them take as many pictures as they wanted. That was quite a thrilling experience.

Donald R. Lennon:

At that time when you made the White House appearance, the choir had not been traveling out-of-state on a. . . ?

Lewis S. Bullock:

No. We had just sang around the state.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had moved to Greenville by this time, had you not? Were you still operating out of Goldsboro or had you moved to Greenville?

Margaret Bullock:

We were in Greenville then.

Lewis S. Bullock:

I think I had moved to Greenville at that time. Made our headquarters in Greenville.Mrs. Bullock: We sang in a lot of churches in the area and they would take collections that would go toward the trip we were planning. We raised a lot of money.

But that tour wasn't just in the White House, we sang in Washington in one of the major churches where G. Sterling Wheelwright was the organist.

Margaret Bullock:

In the Washington Cathedral.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We then went on to New York and sang at the World's Fair.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you arrange that? What did you have to do to organize and arrange for these engagements?

Lewis S. Bullock:

I think we just sent letters.

Margaret Bullock:

Yes. We did it all by mail.

Donald R. Lennon:

You just asked to be allowed to sing in the World's Fair?

Lewis S. Bullock:

It was so long ago, I don't remember.

Margaret Bullock:

You went in to see LaGuardia.

Lewis S. Bullock:

No. That was another tour. That was in 1942.

Margaret Bullock:

I think it was all done by mail.

Lewis S. Bullock:

That tour went over so big that we decided the next year we would do a transcontinental tour. Mrs. Orndorff (?) was president of the Federation of Music Clubs in Raleigh. She had heard the chorus and the convention was in Los Angeles. Since she was president, that's how we were arranged to sing on the program. We said, well we'll just make a transcontinental tour and sing on the way out to California.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were really sponsored by the Federation of Music Clubs?

Margaret Bullock:

In name only.

Donald R. Lennon:

For that concert.

Margaret Bullock:

We represented the state of North Carolina--I think that's Governor Broughton's official representatives. At the White House when the music critic reviewed our concert, he said he had only ever heard one other choir that sounded like this group sounded and that was Westminster Choir.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Mary Grey Harrison, lived in the same apartment building. She became good friends of ours. We wrote letters to various groups. We wrote a letter to Southern Methodist University to give a concert there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Took out a road map I reckon and plotted your course.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Like Little Rock, Arkansas, we wrote the high school there. We wrote to many places. We had to have transportation. We had a little difficulty getting a bus for transportation. We finally straightened our problem out with Trailways.

Donald R. Lennon:

Reliable buses in 1939-1940 period is not quite the same as they are today, I wouldn't think.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We had a little trouble with that before we got back.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the hotel accommodations and things? Was that difficult?

Lewis S. Bullock:

We lived on a dollar a day.

Margaret Bullock:

That was our allowance for food.

Lewis S. Bullock:

The food was a dollar a day per child.

Margaret Bullock:

In many places the children were taken into and entertained in homes. For instance, if we went to a place where we sang in a church, a few people at the church would take the children into homes. Lewis and I had about six or seven adults who went with us as chaperones and we usually stayed in a hotel. Hotels weren't expensive then.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We had this . . . from Governor Broughton making us official Ambassadors of Good Will from North Carolina. When we were approaching Nashville, TN, we were met with a police escort and taken into town. The governor gave us a reception.

Margaret Bullock:

At the governor's mansion.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We were royally entertained. It was quite an interesting thing. Many of these youngsters had never been farther than ten miles away from home.

Margaret Bullock:

Do you know who John Charles Thomas was? The socialist candidate that ran for president so many times. He was at that reception in Tennessee at the

governor's mansion. He was a guest of honor and we sang for him.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Kay Keyser invited the group to Catalina Island as his guests and we sang on his radio program. They had their pictures taken and that thrilled them. Earl Carroll Vanities had a big theater, near there and so I dropped in and I thought it would be interesting. That night, we gave a little program for the Earl Carroll Theater and some of the boys danced with some of the show girls.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the theater receptive to an unknown singing group just showing up?

Lewis S. Bullock:

We let them know that we were quite well-known and interesting and they went along with it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, from their perspective, you were well-known in North Carolina but as far as out in California?

Margaret Bullock:

There wasn't one place that we ever sang that we ever got a bad review or less than welcomed with open arms. You never saw a country like this country was at that time. They embraced those boys and girls as if they were their very own. We had just marvelous entertainment. Rotary clubs gave them meals. One time we arrived late because we had an accident and Lewis didn't get there to start the concert, so we started it without him. I was in the car ahead so I started it. They had taken up a collection for us and when they found out what had happened to us, they took up another one. America today is not like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

That would be impossible today.

Margaret Bullock:

Impossible.

Lewis S. Bullock:

That was in Kansas. Phog Allen, the famous basketball coach that is internationally

known, was at the Rotary Club and saw that my leg was hurt, so the next day he took me down to his office and treated my legs. We had some marvelous experiences.

Margaret Bullock:

One of the most exciting things of all was us giving the Messiah in Raleigh at the Raleigh Memorial Auditorium on December 7, 1941. We were broadcasting nationally and then the broadcast was interrupted to announce Pearl Harbor.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Continuing with the choir--that tour went over. We went in to war in 1941.This was in 1942 (we cancelled all our tours in 1941) so we called it the North Carolina Victory Choir. This time I made the arrangements. We sang in Richmond, Baltimore, and Washington. We wanted to sing in New York, of course. Mayor LaGuardia was mayor at that time so I made an appointment to see Mayor LaGuardia. I told him we were the Good Will Ambassadors from North Carolina. He said, "What do you need?" I said, "We would like to give a concert." He said: "Well, what should we do?" I said, "Well, you can arrange for a place for us to sing." He asked, "Will Carnegie Hall be alright?" I said, "Yes. That would be fine." He then said, “Your young people have to have a place to stay, we will make arrangements at the Waldorf Astoria." So here were these young people being put up at the Waldorf Astoria.

Donald R. Lennon:

That would be three hundred dollars a night now.

Lewis S. Bullock:

For a dollar a night.

Donald R. Lennon:

How far in advance were you scheduling this? For how long before the actual tour did you talk to LaGuardia?

Lewis S. Bullock:

That was about a month.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was just wondering how much publicity they would get out that would bring in a

large crowd to Carnegie Hall to hear a choir like that?

Lewis S. Bullock:

It was given for the civilian defense workers. People mainly in civilian defense.

Margaret Bullock:

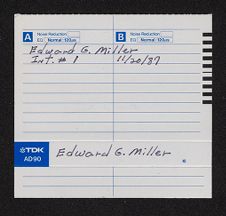

We didn't play in California. We were entertained royally in California in his home by Edward G. Robinson. We had a marvelous, marvelous dinner there.

Lewis S. Bullock:

But it might be interesting because this was such an unusual tour. I made a report to Governor Melville Broughton: “For the first day, Saturday, June 7: The choir left Greenville at 6:30 for Petersburg. Since the choir members came from fifteen cities and towns, it was necessary for most of them to leave their homes at 4:00 am. First there was a concert at the High Street Methodist Church at 11:00 in Petersburg, VA. The choir was entertained for dinner and lodging by various church members. The concert was at the chapel at Camp Lee at 4:00. Another concert at the hospital in Camp Lee at 5:30 pm and a picnic supper was served. A concert was also given at the USO, Petersburg, WVA [should be Virginia] at 7:30. The first day was very busy. We traveled over a hundred and fifty miles and presented four concerts. On the second day, Monday, we left Petersburg for Richmond. We arrived at 11:30. The concert was at Richmond Kiwanis club and members were luncheon guests. We presented a half-hour program. There was a concert at the radio station, WRNL. Concert at the Mosque Richmond Civic Center. It was sponsored by Mayor Andrews and the city of Richmond. Mayor Andrews welcomed the choir to Richmond at the beginning of the concert. The third day, we left Richmond for Washington headquarters Hotel Plaza. Open date. No concert.

Fourth day, there was a concert at the Washington Rotary Club. This was a meeting

where W. Culver(?), General Salvage Chairman of the War Productions Board, heard the choir and later wrote to James Vulger(?), Exec. Secretary for North Carolina, requesting that the conductor write a parody on some Southern song to help with the rubber salvage drive and to sing it on all their programs. This was done to the tune of Dixie, 'America Needs Your Scrap Rubber.' It was sung on two 4th of July programs. A concert at the Ways and Means Committee in the Congressional Building at 3:00. Chairman Doughton of North Carolina (Congressman) heard the choir and said if they could hear music like this more often the country could get better tax bills. We left Washington for Baltimore at five o'clock. There was a concert at the Christian Temple in Baltimore and then left for Princeton, NJ, for a concert at the country estate of Dr. John Finley Williamson. Dr. Williamson gave a tea in honor of the choir. Dr. Williamson told the choir that they were rendering a great service at a time when so many of the forces of the world were trying to destroy beauty. You have the honor to create beauty and continue in that duty and help build a better world. We left from New York at 7 o'clock. On the sixth day, Friday, in New York City at headquarters Waldorf Astoria at 7:00. For a concert at the Fred Waring Program in the Vanderbuilt Theater. The seventh day was open date for sightseeing in New York. On the eighth day, we gave a concert at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. It was a special recital for choir boys. This is the first time a choir ever sang in the cathedral while the famous choir boys listened. The cathedral organist played several selections for the choir on the great cathedral organ.

The ninth day, we left New York for Hartford, Connecticut, concert at the West Middle High School Auditorium, Hartford, Connecticut. The city of Hartford sponsored the

concert. Dr. Alex Messendorf(?), former professor in the Petrograd Imperial Conservatory in Russia and the Russian Cathedral Choir of New York City expressed amazement at the quality of the choir. Boston headquarters Hotel Statler. This famous hotel dedicated twin rooms to the entire choir, Concert Exchange Club of Boston. The governor of Massachusetts and many outstanding guests were at the luncheon including Mrs. Colin Kelly. For our final number we sang the benediction and dedicated it to Mrs. Kelly. The city of Boston gave a dinner in honor of the choir. The choir spent some time visiting Paul Revere's home and old North Church and so forth. We sang at the historic Boston Common. The city of Boston sponsored the concert. Mayor Maurice J. Tobin welcomed the choir to Boston and insisted on an early return. A twenty-piece orchestra played during the pause between groups. Boston gave us a welcome. Left Boston for New York, Headquarters Waldorf Astoria.

Concert at Carnegie Hall. Victory Concert sponsored by Mayor LaGuardia and the city of New York. The mayor could not attend the concert because it was the day he was entertaining the king and queen of Greece in a banquet that was being held that evening in their honor. The mayor wanted to greet us at the city hall the next day, but it was impossible because we had a concert that night. The manager of the Waldorf Astoria was very kind. He greatly reduced the rates to make it possible for us to enjoy this delightful hotel. The choir enjoyed a banquet after the concert at the Starlight Roof. The twelfth day we left for Washington DC and arrived at Hotel Plaza. The concert was at the United States Capitol. This is one of the most thrilling concerts. We sang on a platform directly in front of the capitol. Our flag was flying on the capitol. The weather was perfect. The moon was

just rising above the dome. We will never forget the singing of the national anthem. All the soldiers and guards were at attention. A bomber was flying overhead. The air was electric with patriotism. The enthusiastic audience said it was an evening never to be forgotten. Congressman John H. Kerr was responsible for arranging this unique concert. We had the unusual honor of being the only choir ever allowed to sing at the capitol. Only two organizations are allowed to concertize there: The U.S. Army and Navy bands. Special permission was granted by Vice President Henry A. Wallace for our victory concert. We left for home at 7:00 and arrived in Greenville and gave a concert at the Greenville Kiwanis Club. I personally, as conductor and East Member, am very grateful to our gracious governor for helping make this victory tour possible by granting us a commission as the American Victory Choir of North Carolina. We shall always be grateful to you, Governor Broughton, for your interest and assistance. We trust we have proven your faith in us in service to our beloved country and state. Most gratefully yours, Lewis S. Bullock.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow!

Lewis S. Bullock:

That was quite a tour wasn't it.

Margaret Bullock:

Ethel Merman was at the concert on the Starlight Roof that night. All the choir members got to talk to her. She talked to them just like we are talking.

Donald R. Lennon:

I bet you were exhausted by the time you got back, weren't you?

Margaret Bullock:

I couldn't do it again.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just listening to the itinerary was enough to wear me out.

Lewis S. Bullock:

That was the end of our touring. Along came the war and the draft for me. I knew I would be going pretty soon.

Donald R. Lennon:

How old were you at this time?

Lewis S. Bullock:

Thirty-three. I was wanting to get in as a music advisor in the war department. The United States Treasury invited a group to attend a meeting in the Yale Club in Washington for three days. They were setting up a nationwide music program with community singing. Marshall Bartholomew, the head of the Yale Glee Club, was there with various people from all over the country. I represented the South at that time. Colonel Bronson, who was in charge of the music in the Army was one of the members of that same group. I was going to be a member when the war was all over. I thought that would defer me for awhile . . . heading up the South in this. All of a sudden, it was all disbanded. Music and money was so tight at that time. [I thought] well, I had better see what I can do. So I wrote Colonel Bronson. He said if I had seen him at that time, he might of been able to get me in the War Department as a music advisor. At that time they had cancelled all future. . . .

Margaret Bullock:

When the war was getting very heavy. . . .

Lewis S. Bullock:

. . . future commissions from civilians. I went to Fort Bragg in the infantry.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were drafted, straight into Fort Bragg.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Went to Little Rock, Arkansas, for my basic training.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, before we get into the second phase of your career, I would like for you to think back on the North Carolina phase of it, the community choruses, the Eastern Carolina Symphonic Choir, and the tours and see if there is anything else, with regard to any reflections, on how you were able to pull apparently such talent. . . .

Lewis S. Bullock:

Once they learned a little of Bach and Palestrina, they loved it. They didn't know anything about it before. When I decided to give the Messiah, that was kind of unheard of

for these adult choruses. We rehearsed and rehearsed and we learned it and gave the Messiah in each of the cities around. Mrs. Orndorff(?) at the Music Club in Raleigh, that is, they invited the group. We had to put them all together, about two-hundred and twenty voices for the concert at Raleigh Memorial Auditorium on December 7, 1941, when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Margaret Bullock:

I hope Malcolm has a tape for you of that Messiah. I hope you will listen to it. It is absolutely beyond belief. Remember this, these are men and women from every walk of life, no previous training, all at his fingertips. He was the conductor. The Raleigh Symphony Orchestra accompanied, but the choral work he did.

Donald R. Lennon:

How difficult was it to find the talent from those original choruses that pooled together?

Lewis S. Bullock:

The high school?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

Lewis S. Bullock:

It wasn't too difficult. They had natural voices. Sometimes it is easier to train somebody with just a natural voice than somebody with a lot of experience who has learned a lot of bad habits. They hadn't learned any bad habits in singing. It was very easy to train them. I'd play over the soprano part one time and [say] "Alright now you sing it." They would sing it.

Donald R. Lennon:

You make it sound easy.

Lewis S. Bullock:

The singers would memorize the whole program. They learned a program that was the equivalent to the Westminster Choir with several parts. Some of the numbers were in eight parts and they would memorize the whole thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said that none of them could read music. It all had to be from memorization.

Margaret Bullock:

They learned it by roles. There are members in Eastern Carolina. Did you ever know Mrs. Proctor in Greenville?

Donald R. Lennon:

There are several Proctors in Greenville.

Margaret Bullock:

I think she died recently. She was very prominent in this work. There was a Mr. Smith, a tobacco man, and his wife, who was the organist at the Presbyterian Church. I had forgotten his . . . but she was a wonderful, wonderful help to us in Greenville. Then there was the minister of the Christian Church. I've forgotten all these names. There were people in each of these places that were so touched by what these young people are doing.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We got sponsors. We would give this festival concert each year. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Thinking in terms of young people today, they have such varied interests and demands on their time. I would have thought a lot of these farm boys such as Mr. Hill, would have been more interested in being outside playing baseball, or something of that nature, rather than going to choir practice.

Lewis S. Bullock:

They had to give up their Sundays for about eight weeks in a row.

Margaret Bullock:

The whole Sunday afternoon. There was not even one that wasn't there.

Lewis S. Bullock:

The spirit of that group and what they thought they could accomplish. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

How were you able to motivate them to be interested in this type of music when it wasn't something I am sure that they had grown up with? This is what I find fascinating.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We just started and said, "Let's sing this." They got so they liked it. Imagine them

singing a little Bach: "Now let every tongue adore thee." Palestrina and Handel.

Margaret Bullock:

The program for the concert they gave at the White House is in one of those books hanging on our wall. When I look back on it, I am really just amazed at what we did accomplish. Even the New York Times critic said they were comparable to the Westminster Choir.

Donald R. Lennon:

It amazes me that the New York Times would send a critic to listen to a Southern high school group like that.

Margaret Bullock:

They did. We have just touched a few of the highlights. The boys and girls, were remarkable, because I think everyone of them adored Lewis. I think they were fascinated with his conducting and his controlling them as a unit such as taking all the sopranos and making them into one voice. I know we went back to a reunion recently in Snow Hill and one little girl said: "Mr. Bullock, I couldn't go on the tour because I couldn't possibly raise $25.” But she said, “I am so thankful for what I had. You know, you used to say, `I hear some air' and I always knew you were pointing at me. I don't know whether it was or not, but I thought it was me.” There are any number of them through eastern Carolina right now, in Ayden and Winterville and in Snow Hill. One of the boys who was very prominent, Bill Taylor, died about two months ago. He was about sixty-five years old. It was quite a shock to us. Of course, you recognize Malcolm [in the picture]. He attributes all of his success to Lewis. On June 3, we will have been married fifty-seven years. We started out with Malcolm almost the first year we were married, so you know how long he has been loyal.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are there any other thoughts about the North Carolina phase of your career before

we move on to your military phase?

Lewis S. Bullock:

No that is about all I can think of at the present time.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were then drafted and went to Fort Bragg and from there sent to Arkansas for training?

Lewis S. Bullock:

Yes. Basic training.

Donald R. Lennon:

After basic training?

Lewis S. Bullock:

I went to a new camp in Texas, called Camp Fannin. They had no trainees there, just a very few except the Cadre. It was a new camp that just opened. I was just sort of marking time there until I was to be assigned somewhere. I found out Commander Regnier was interested in music and he had a glee club that he started. That interested me so I was going to the rehearsals. A lieutenant was in charge of conducting the group. The lieutenant had to be away sometimes and the colonel found out I knew something about conducting so I conducted the group a few times. So he said, "Well, you are in charge of the chorus from now on." That was an interesting group. From the various companies, the members of the chorus would line up, and they would be marched in columns of twos into the chapel where we would rehearse. At a certain time, you would see these columns of two from various units. There was a large group of them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were these volunteers or had they been selected from the typical military. . . ?

Lewis S. Bullock:

They were volunteers, but as an incentive in joining the choir the men had to have no KP or guard duty.

Donald R. Lennon:

Even if they couldn't sing.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We sang around in many of the churches and so on. They were going to put on a big

show, "Texas Yanks," an IRTC Camp Review. I wrote two songs for it--the “Song of the United Nations” and "Soldiers of Freedom." It was quite a big production.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is this still in 1943?

Lewis S. Bullock:

That must have been about 1943 or 1944. We gave a big production in Dallas. Red Skelton was part of the program.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you a private at this time?

Lewis S. Bullock:

Yes. I was a private waiting to be assigned somewhere. The only thing that seemed to be open was the combat platoon leader at Fort Benning. So I applied to see if a musician could be a Combat Platoon Leader and so off I went to Fort Benning. There was a very serious physical test during the twelfth week of the sixteen weeks you went through. One part [of the test] was running and picking up a grenade and running back [to your starting point] and turning and going to pick up another one. Just before that, we had a night problem and I fell into a hole and sprained my knee. The captain thought that I shouldn't try it [the grenade test], but I wanted to graduate with my class. I missed it by about 2 or 3 seconds and I flunked the physical.

Margaret Bullock:

Which was a blessing. The whole unit was sent into the Battle of the Bulge. Over ninety percent of them did not come back. The fact that he was held back, I think, saved his life.

Lewis S. Bullock:

That was what it was like being a private waiting to be assigned somewhere. Lo and behold, my wife eventually went and saw the commanding general at Fort Benning. I don't know what in the world she said.

Margaret Bullock:

I just walked in and told him that I wanted to talk to him. He was as

nice as could be.

Lewis S. Bullock:

He said that if I wanted to start at the beginning and go all over again I could start at the beginning.

Margaret Bullock:

They were going to send him out to “PoDunk” or somewhere.

Lewis S. Bullock:

So after twelve weeks, I started at the beginning again at Fort Benning.

Margaret Bullock:

By the way, there is a book on the "Texas Yanks." We've got a book with the “Texas Yanks” program in it.

Lewis S. Bullock:

It [going through Fort Benning a second time] was easy, because I had already been through the twelve weeks once and I knew all the problems and what to expect.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you tell the general? What were you asking him to do?

Margaret Bullock:

I was afraid that the fact that he had missed it would make him so discouraged inside, because I know his character. I knew what he could accomplish and I knew that he felt it terribly not to go on with his group. I went in and told the general that. I said, "If you are going to send him somewhere, why not let him do the whole thing again. It will hold him in this country and let him do it until he accomplished what he has set out to accomplish." He was wonderful. I told him [Lewis] this about a year or two ago. I never told a living soul in my whole life. The audacity of me, a little nobody. I just walked right into the general's office and knocked on his door and he said, "Come in." He was wonderful. He was absolutely charming and wonderful and was just as nice to me as he could be. He agreed with me completely and orders went out immediately that he was to repeat it [his training].

Lewis S. Bullock:

This group was rather a nice group. These were older fellows and we had quite a

nice glee club. One of the fellows, Hauptman (?) was getting married. I sang at his wedding. He came to see us about a year ago and we found out he is a major general in charge of the retired officers association of the whole United States. He was attorney general in Iowa. This group had arrangements to go to Warm Springs and sing for President Roosevelt. A few days before we were supposed to go, was when he died.

Margaret Bullock:

We went to Warm Springs and he had just died when we got there. I was on the bus with them. We went on one of those Army buses that bounces you up and down.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We went down to Camp Blanding.

Margaret Bullock:

[By then, this was 1945.] Just before the war was over.

Lewis S. Bullock:

I was an IRTC instructor then. We were coming from Fort Benning. We were training these young people to go overseas--this infantry. They thought I had a lot of experience and had been overseas. I had my own jeep going around grading night problems. When that was over, I applied for special services, but I guess the choral music didn't attract them or whatever. I didn't get that appointment, but I was sent overseas for the 86th Blackhawk Division. They had been in the European command and then they sent them over. . . . The war was just over. They didn't send me overseas. The reason they didn't send me over was an age limit for combat platoon leaders. I was just over the age limit to be a combat platoon leader, which is what I was trained for. The war was over when I was sent overseas. They were just cleaning up operations.

There I was in the 86th Blackhawk Division. I cooked up this choral music project, singing and details. I took it into Base X, that was the Manila area. They thought it

sounded rather interesting. The colonel said, "By the way, we are giving the Messiah." I said, "Oh, the Messiah." I went down where they were rehearsing at the Ellinwood Church. The group was made up of Red Cross girls and local church choirs--big group of over two hundred. The fellow who was directing it was a chaplain in the Navy. When he found out that I had been to Westminster Choir College and had conducted the Messiah many times, he said, "Here, I don't know much about this." So I was made director of the chorus, the Messiah chorus. The Base X liked the idea of this choral music project and they put me on vocal orders. I didn't have any written orders. I was given vocal orders by the commanding general, of the 86th Blackhawk Division, to go to Base X and work with the music in the Manila command. We couldn't give the Messiah because the orchestra. . . . Dr. Zipper was conductor of the Manila Symphony Orchestra which had stayed underground all during the war. It was still intact. It was quite an unusual symphony orchestra, but the orchestra parts never arrived from the States. All we could do was to give a concert at Christmastime at the Rizal Coliseum, and at the Roosevelt Club, in Manila. The symphony played Beethoven's Fifth Symphony and the chorus sang selections from the Messiah that we had learned. We couldn't give the whole Messiah because the orchestra parts needed never came. While we were rehearsing the chorus, I selected about seventy of the best men and said: "Let's have a male chorus of just the GI's." We rehearsed on our own after the big group rehearsed. They rehearsed on their own time and they came from the various outfits. Then I had an idea. We selected a smaller group--like a touring group--and we pushed that through to Base X. That was an unusual group because they were transferred from their various outfits and put on temporary duty to sing in this male chorus.

We had officers in the Rizal Coliseum. We had a captain in the chorus, a master sergeant, and I was a second lieutenant. I was called the commanding officer of this group. We had two Australian Army personnel and from the Philippine Army which is why we called ourselves the International Male Chorus at that time. We gave our world premiere in February 22-23, at the Manila Leaf Center. General Trudeau, who was commanding general of Base X, was at the concert. We gave two concerts that went over very well, so we then started touring. We sang at Cavite and all the various bases around Manila.

We later decided it would be nice to go to Japan and sing there. We knew that would be more difficult, but Colonel Doyle was my commanding officer. We called him "Check Sheet" Doyle. You didn't talk to him personally, you had to write him a little note. He said that it was impossible to go because of personnel problems and transportation problems--Japan was out of the question. That didn't stop us. A letter came back from the colonel in Japan saying, to the effect, that there were personnel problems and it was a large group, but if we had some smaller group to let him know.

In the meantime, Base X consolidated that area. Lieutenant General Styer came in as commanding general of the whole area, not just Manila, which was called Base X, which was the whole western Pacific. Well, he hadn't heard the chorus, but we found out that they were giving a West Point Banquet and we knew that he would be at the banquet. So we said, "We will have to sing at this banquet." I called up the lieutenant in charge. He said, "Well, it is a little bit late. All arrangements have been made so it is impossible to get the chorus on the program." I called up General Trudeau, the commanding general at Base X, because I knew that he had heard the chorus at our world premiere and suggested it to him.

He said, "Yes, that sounds like a great idea. Come have lunch with me." So I went to have lunch with him and he asked "Well, do you know any of the army songs like 'Benny Havens,' old 'Army Blue'? God it would be nice if you could sing 'The Corps.' No, no. That is too difficult a number, I know you couldn't do that." I replied said, "Yes. We can sing some of the songs." I went back to the group and said, "Well, boys, we are going to sing but we don't have any of the songs, so scatter out and see if you can find an Army songbook anywhere." I think around eight o'clock or something, one of the lieutenants--we had several lieutenants in the chorus--came back with an Army songbook with all these Army songs in four-part male chorus arrangements. We mimeographed them all off. We sat up most of the night and we memorized all these songs, "Army Blue" and we memorized "The Corps" and that's a tricky number. The night of the big banquet, we had a concert at the 86th Blackhawk Division, the division that I was assigned to, and so we had to keep that but I cut it a little bit short. We had a MP military escort, with sirens. The camp was about ten miles away, the 86th Blackhawk Division, at Marikina from Manila. We got back just in time to sing for the banquet and we sang our few songs. Then we struck out with "The Corps," and they sprang to their feet. When we finished singing that "Corps" we got an ovation you never heard the like. General Styer came up and he said, "I heard a lot of nice things about this group. I'm glad that I heard it. Is there anything we can do?" I said, "Well, I have a few ideas, General." He said, "Well come up and see me." I went up to see him. I said, "MacArthur sends many things down from the big command in Tokyo down here. We have this outstanding group, why don't you send ours up there to show him up there that we have something down here." That kind of tickled his fancy, I think and, he said, "Yes. That

sounds like a good idea. I will make the arrangements." Then I said, "Another idea that I have, too, is all these men are just about ready with enough points to be discharged. Wouldn't it be a good idea to have the group go back to the United States as an Army group to sing for the Army hospitals and so forth--to show the American people what had been done in the Army by the Army." He said, "Well, that might be a little more difficult to arrange that, but see me when you come back from your Japan tour."

So we made our tour with a little difficulty getting planes to go, but the general gave us two planes, one was his own plane. I had fun sitting in the general's compartment pretending I was the general on the trip over to Japan. That was an unusual tour. We sang in Okinawa, held many concerts all throughout Japan, especially the Ernie Pyle Theater. We got rave reviews in the Army magazines and so on. I remember we had one day off. So I got on a train, by myself, and took a little ride out to Hiroshima to see what had happened there. That was a strange feeling, I was on a packed train and I was in the uniform of an American soldier who[se country] had just bombed Hiroshima. I had no trouble with nobody.

Donald R. Lennon:

That area was not off limits as a result of the bomb being dropped that recently?

Lewis S. Bullock:

It was sort of off limits, but I thought it would be alright. I thought I would like to see.

Donald R. Lennon:

You weren't concerned about the danger?

Lewis S. Bullock:

I went and saw it anyway.

Margaret Bullock:

I don't think he was ever afraid of anything in those days.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did the Army command, MacArthur's command, in Tokyo react to the

chorus?

Lewis S. Bullock:

There was a terrific reception. We gave three concerts in the Ernie Pyle Theater in Tokyo. We got rave reviews in Okinawa. But we were right back the 3rd of July. The big ceremony for the independence of Philippines was on July the fourth. We wanted to get back in time for that, I made arrangements to sing on July 5th at a big ball at the Malacanang Palace. The chorus sang the “Ballad for Americans” on that program. MacArthur was there. He signed our tour book. Many of the world leaders were there and we got many good reactions from that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your comments a few minutes ago triggered in my mind how conscious the military is of following the chain of command. I noticed several times when your CO didn't give you the response you wanted, you went right up the line to the general. What kind of reaction did you get from the officers?

Lewis S. Bullock:

My “Check Sheet” general knew I was a little bit . . . then he was quite delighted when it was all over that somebody from his command was making this trip to Tokyo.

Donald R. Lennon:

I have seen military officers that did not want anyone to go over their head for anything.

Lewis S. Bullock:

They didn't either. We were kind of an unusual group. We did a lot of unusual things.

Donald R. Lennon:

There were no repercussions.

Lewis S. Bullock:

No, No.

Margaret Bullock:

It's a wonder there hadn't been, though. It is amazing he didn't get court-martialed.

Donald R. Lennon:

It really is.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Now can we go back to the States. I had already lost a couple of my good men, because they almost all had enough points to return to the States. General Styer had said to contact him when we got back from our Japan tour about going back to the States. When we returned on July 3rd, Lieutenant General Styer had returned to Washington. He had an emergency appendix operation, so he had to leave his command. Major General Christiansen was now the commanding general who knew nothing much about the chorus at that time. I went to the general suggesting that we make this tour of the hospitals. He ended up by saying, "Well, if any group should go back it ought to be a combat group or something, not a chorus.” And he said, “And I'm the general.” I replied, "Yes, sir." I saluted and out I went, but that wasn't the end of it. On the sixteenth of July, the International Male Chorus received a letter from General Christiansen: "Members of the International Male Chorus, I wish to take this opportunity to congratulate you on your achievements in the field of entertainment and music. In a few short months, you have become known and appreciated throughout this command in Japan and Korea. You have made a definite contribution to the morale of this command. I wish to express especially my appreciation to those who volunteered their services beyond the tour of duty, and those not of the Army, who generously offered their time and talent, so that the military personnel of this command might enjoy a moment removed from their work and everyday surroundings. Sincerely, Major General Christiansen." This was same general that said we shouldn't go back to that States. Many of the members of the chorus were already at the Tacloban(?) Replacement Depot, waiting for a ship to return to the States. We were supposed to

be disbanded, but I requested a temporary restraining for us to give a sort of a farewell concert at the Rizal Coliseum. I said, "Well, we ought to at least give a farewell concert." We were buying some time. So we gave this farewell concert on July 17th. We put money together and I made a personal long distance call to Washington for General Styer. I reminded him of our desire to return to the United States and that he had told me to contact him when we returned from our Japan/Korea tour. General Styer told me to ask General Christiansen to send a request to the war department to have the male chorus returned to the States as a unit, for the purpose of making a tour of armed forces installations prior to being demobilized, and to give my name [General Styer] as reference. He said he would see General Eisenhower that day on the subject. In the meantime, since we were told that our return to the United States was impossible, I went to see the President Manuel Roxas of the Philippines and suggested that we combine some former members of the chorus from the Philippines with the Americans and make a tour of the United States to raise funds for the New Philippine Republic. He said that he was interested in the idea. When the Army brass found out that I had contacted a Philippine president, they were quite upset. I was told to stop any future arrangements.

Donald R. Lennon:

They had a maverick on their hands.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Well, I thought, we had to get back some way. General Christiansen sent a communiqué to General Styer in Washington. He stated what I had said to General Styer in my telephone call. He said "Not known to me were your plans or desires on this matter. In view of acute personnel shortage and eligibility for return of many members, instructions have been issued to disband chorus eighteenth July. They will be held in obeyance. I

believe that the tour will not pay sufficient dividends to warrant the special treatment. This case will have to be given and recommend that the chorus be disbanded here as planned. Of the eight officers and twenty-one enlisted men now in the chorus, seven officers and sixteen enlisted are eligible to return to the States for separation on your current criteria within the next thirty days. All have expressed willingness to remain in service thirty days beyond normal separation time for purpose of tour. After that time losses would progressively upset musical bounds. This matter is not being taken up with either AFPAC or War Department pending receipt of information from you as to your desires."

July 19th, from General Styer to Christiansen: "Reference in view of condition stated, reference depletion of personnel in International Male Chorus. I concur on your views and will take no further steps to arrange U.S. tour. You can proceed with disbanding in accordance with your plans. Inform Bullock. I regret that we could not arrange for a tour of full chorus." Through our grapevine, we could find out the communiqués being sent out and received. This certainly looked like the end; however, most of the chorus was still intact and some members were already at the depot waiting to leave. As our last parting gasp, I sent a rather lengthy telegram to General Styer, as follows: "Talk to General Christiansen, about his Colonel Mackin personal opinion of our chorus returning to States not worth trouble. Many great leaders differ in opinion. Great part of chorus mission unfulfilled. We are holding great message from thousands of people, great loss. Chorus could be powerful factor for peace, goodwill. Is bringing message goodwill, good music, as sung by the International Male Chorus to veterans, hospitals, Army camps, concert halls throughout country, worth effort, expense? Ten thousand unheard Americans cry out 'Yes!' What say

you and General Eisenhower, who told chorus had great mission. We believe you men of vision also say yes. Unlimited effort, billions spent defending, destroying and so little effort is spent to help build peace. Goodwill concert tour of this famous Veterans Chorus would be acclaimed one of Army's great contributions. Disbanded chorus on paper, but rehearses evenings. President Roxas request benefit concert war widows, still serving until end. Great chorus still intact. Men at depot. Those soon going still have faith the way will be open to continue our mission."

Donald R. Lennon:

General Christiansen didn't call you in and just chew you out to have called and then sent a telegram. This was absolutely one hundred and eighty degrees contrary to what Christianson(?) had ordered. This would be grounds for court-martial.

Margaret Bullock:

Why he didn't get court martialed?

Lewis S. Bullock:

It was a hundred and fifty-seven word telegram. I don't know how much it cost. Well, I got it off my chest. October 1: GI Colonel Mackin wanted to know what I said in my cable to General Styer. He is the G-1 colonel. Answer: "The following is the approximate sentence of cable dispatched to General Styer on Thursday the 25th of July, 1946. Reported outcome of talk with General Christiansen that we requested(?) not being able to continue our mission of music and good will to the armed forces of the United States, including Veteran's Hospitals, and Army Camps. We had been disbanded on paper, but will still rehearsing evenings on our own time. President Roxas asked us to give benefit concert for Philippine war widows and orphans, but we are continuing to serve until the end. There are men in depot and those soon still had faith way will be found for chorus to continue it's mission. Signed Bullock." The reason the GI asked this information was for

the following cable to General Christiansen from Washington, DC, on the thirtieth of July. "To General Christiansen, referring to radio 272104 for Lieutenant Bullock. I have discussed the possibility of returning the International Male Chorus to U.S. with General Reynolds, who believes that the chorus could be utilized to advantage for entertainment in Army hospitals, providing sufficient personnel can be returned in a group composed of appropriate voices to insure a well rounded singing group. If possible, to return such a group on the same vessel who are eligible under present criteria, General Reynolds suggests this be done that he be and advised of the name of the vessel, the approximate time, port of the debarkation and that Lieutenant Bullock or the officer-in-charge telegraph him on arrival. It will probably be necessary for members of the group to agree to the extension of the duty demobilization by sixty to ninety days in order for the tour of hospitals to prove feasible and is approved by War Department. Decision in the continuation of the chorus as a group to tour hospitals and possible other areas will be deferred until arrival in the United States. Please inform Lieutenant Bullock of your decision concerning the above and keep General Reynolds informed. If the War Department asks, it is suggested that the group sing under the name "Male Chorus of the Armed Forces of the Western Pacific." We could hardly believe it. What a miracle!

[End of Part 1]

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| Mr. Lewis S. Bullock | |

| February 23, 1996 | |

| Interview #2 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Pick up right there with the approval for the members to return to the United States.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We could hardly believe it. Already some of the group had been sent back despite General Christiansen _______. We'd been put on hold. I made a protest and all the remaining chorus members were put on hold right away. We had Washington behind us all right, but we were still short of voices. Not to give up, we combined our ranks to those at the depot waiting for return to the United States and boosted our group to a total of twenty-seven. The plan called for us to be ordered to our various separation centers in the United States, but were authorized to delay seventy days en route for a concert tour of the U.S. There was a fight, but we came out on top. We were all excited about remaining together and maybe we could play in Carnegie Hall after all, but during our long voyage home, we made good use of our time. The new members we had picked up at the depot had to learn all the concert programs before we arrived in San Francisco. We rehearsed every one of the seventeen days aboard ship and steamed into the home waters with high hopes.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of ship were you on? What did they book you on for your return?

Lewis S. Bullock:

We were in the SWALLOW, was the name of the ship. It was a seventeen day trip back.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it an Army ship?

Lewis S. Bullock:

It was an Army ship. We gave our first stateside concert at the Letterman General Hospital and then afterwards we'd break up into small groups and sing for the men confined in the wards. The next stop was the Pasadena Hospital and then another one in Los Angeles. We sang to warm appreciative audiences. Charles Henderson said, “I'm grateful to hear a chorus who've given me one of the greatest musical thrills of my life.” Laura H. Mack (?), the _____ Special Services said, “Please accept my thanks on behalf of all the patients of McCornack General. It is the greatest musical treat we ever had.” Near the end of our time in _______, we transcribed an all Army, fifteen minute segment of “Sons of Guns,” seventy-five radio stations featured the program. The commanding general of the 6th Army cabled the Adjutant General that we had surpassed the popularity both of “Proudly We Hail” and “Warriors in Peace.” He went on to recommend that assuming Special Services would release our unit, we should be considered for use in the recruiting service, in so much as the quality of performance was believed to be on par with the renowned Don Cossacks, but the war was over and funds were short and so our tour was canceled.

Margaret Bullock:

May I interrupt? Didn't you go first though when you were discharged as a unit? You went and you were discharged as a unit. You're talking about going on singing. The first thing you did in California was to go to be discharged and you were discharged as a unit.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you discharged before you sang at the hospitals?

Lewis S. Bullock:

Oh, no. In the Army, we were supposed to stay in for three months and travel all over.

Margaret Bullock:

You had been discharged when I got out there.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We weren't discharged yet. The war was over and the funds were short and we were canceled. Once again, we faced extinction without military funds. I thought perhaps we'd get some private help, so we sang for Atwater Kent in Pasadena. His foundation thought it might be able to help. We contacted Special Services in Washington with a prospect. General Reynolds replied, “Lieutenant Lewis Bullock, officer in charge, AFPAC Choral Group now at your station as follows. Regret impractical to authorize tour of chorus by private benefactors, convey appreciation to Atwater Kent. Signed, Reynolds.”

We were still in the Army and at that time, we were all supposed to go to separation centers all over the country. We still wanted to stay together except a few of the men that were married and thought they had to go home, so I went to General Merrill, ____________ was the commanding general there. We asked if we could all get discharged as a unit. He said, “Hell yes, if that's all you want.” So, all of the chorus was discharged there and .... Now, we're in San Francisco, civilians. What should we do? At that time, Margaret, my wife joined us in San Francisco and she would become our secretary, treasurer, acting manager and mother confessor. She combined an annual scrapbook for the chorus including clippings, reviews, news stories, pictures and that later became vital in the preparation of preservation of the IMC. Rudy Vallee was in Los Angeles. We sang on his program. He called us the American Don Cossacks. We had to do something, so we rented the Opera House in San Francisco and said, we'll give

a concert. We thought that being right out of the service at the Opera, they'd give us a break on the rent, but they didn't. We paid the regular fee to rent the hall. I decided that as a chorus well, the only thing we could do was to sing for a few radio programs and a few of the city clubs and then we have the major department stores. We printed tickets and then we had booths and giving out free tickets all over San Francisco. I forget how long that was. Do you remember Margaret?

Margaret Bullock:

About a week.

Lewis S. Bullock:

But, we filled the hall and then we took up an offering. We cleared over three thousand dollars that night.

Margaret Bullock:

I remember that one check for five hundred dollars and I was flabbergasted when I cashed it. I couldn't believe it.

Lewis S. Bullock:

That worked out pretty good, so then we went on down to the Philharmonic auditorium in Los Angeles and we did the same thing, singing for some high school assemblies and Rotary Club, Kwanis Club, and things like that and then we filled the auditorium again.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you still calling yourselves International Chorus?

Lewis S. Bullock:

International Chorus, yes. We didn't change that until quite some time later. It happened that Mrs. Edward G. Robinson was in the audience at our concert and she became interested in the group and she invited the whole group to her home for dinner. At that dinner, John Garfield was there and Sol Speigel, who was one of the big producers at Warner Brothers and we sang several songs. Sol Speigel invited us to have an audition at Warner Brothers. He was hoping they would make a short of the chorus. We had our audition and the audition went very well, but then he told me that we

needed a manager. They don't do things unless they go through the manager. So, Mrs. Edward G. Robinson was a friend of....

Then our next concert, we rented the auditorium in Pasadena, but we thought we'd try a new trick this time. Instead of giving away free tickets, we'd sell sponsor tickets. I think it was five dollars a sponsor and the men in the chorus...the one that sold the most tickets was J. P. Stevens, Jr. He was a member of the chorus. We didn't realize at the time that he had a lot of contacts all over. He was supposed to enter Yale that September, but he stayed with chorus and didn't enter Yale until the next semester.

Margaret Bullock:

Did you put in about me visiting Mr. Edward G. Robinson? You left me out.

Lewis S. Bullock:

When we went to dinner, you spent an hour with Edward G. Robinson. He had quite a collection of paintings.

Margaret Bullock:

He really had the most famous collection in the country at that time and he had built on an extra extension to the house and that whole extension was filled with his art and he took me around and explained everything, all that, over an hour. It was quite an experience. That was before we had dinner. The whole group had dinner with Edward G. Robinson and in this book that I've made about myself is the last picture that his wife sent to us from Paris. It's in the book that I got together about me and I'm ready to give it up, but Lewis, because it's all pictures of me in it, he doesn't want to give it up right yet, but you'll get it eventually.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Mrs. Dalbert(?) in Los Angeles, she's one of the big hostesses, gave a party for the chorus in her beautiful home. We had quite a few of the entertainment stars there,

Barbara Britton, Arlene Judd, Cesar Romero, Bing Crosby, were there. We had a tour book that we had with us and people would write in our tour book that we had from the beginning of the chorus. Cesar Romero wrote in our tour book, “I've heard beautiful singing before and I've been deeply touched by it, but it took the International Male Chorus to completely knock me down with their beautiful rendition of the Lord's Prayer.”

Donald R. Lennon:

How many were in the chorus at that time?

Lewis S. Bullock:

There were about twenty-six. The next thing we found out was the thirty-third annual Examiner benefit show at the Shrine auditorium was to be on December the 12th, so I went to see the manager of the thing and he agreed to put us on the program to sing the Lord's Prayer at the end of the performance. There was a capacity crowd there of over ten thousand. Greer Garson served as MC and her counterpart MC was Bob Hope, Red Skelton, Monte Blue, Ralph Edwards, all the big names in the entertainment business; Josè Iturbi, Marilyn Maxwell, Edgar Bergen, Vivian Blaine, Dick Haymes, Abbot and Costello, Kenny Baker and we had our pictures taken with some of the stars. During that time, we traveled to Cleveland and gave a concert for the American Legion National Convention in Cleveland and by that time, we realized that we might have a future after all and we all decided by that time, we'd disband for the holidays and we'd come back after the holidays.

Donald R. Lennon:

Logistically, performing in Cleveland and California, you were depending primarily on both sponsors and contributions, people making contributions at the concerts, what were the logistics of getting to Cleveland and were the Shriners paying for your...?

Lewis S. Bullock:

We were on our own then. I don't remember how...

Margaret Bullock:

We didn't have a bus then. We later had a bus, but...

Donald R. Lennon:

I was saying it's kind of expensive to get twenty-six people from California to Cleveland.

Margaret Bullock:

I think everybody just paid his own way.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We had the three thousand dollars from those concerts.

Margaret Bullock:

The ones who didn't have it, probably we used that money for them. For instance, Pete Stevens, he didn't need any help. By the way, we got a Christmas card from him this year and one member of the chorus, I don't know whether you've got him singled out, was a little black boy, named Harry Arrington and he was just about this tall and he was cute as a bug's ear and I haven't seen him since then. We've had at least a card once a year from him and we just had a Valentine from him. He's become very religious and on every one of them, he's written, “God loves you and so do I.” He always addresses on the outside, “Mr. Lewis & Margaret Bullock.” I always called him my chocolate drop and he always signs it, “Your Chocolate Drop.”

Donald R. Lennon:

That wouldn't go over very well in the climate today.

Margaret Bullock:

He still does that with me. I'm sure he wouldn't do it with anybody else. As far as I'm concerned, he's my chocolate drop.

Lewis S. Bullock:

So, we came back on February the 22nd. We met in Washington, D.C., I don't remember just how we did it, but we found an old empty government building that they let us use to rehearse in and then we sang for all the service clubs, Rotary Clubs, all over Washington and we gave our concert in Constitution Hall, which is actually sort of a preview concert for our concert that we were going to give in Carnegie Hall. That concert went over very well. We had very good reviews in all the papers. We needed a concert manager. Mrs. Robinson, she gave me the letter of introduction to Sol Hurok, who was the big shot at that time, but he was in Europe and we needed a manager quickly. So, we went around New York trying to find... I finally decided on the Jack Adams agency. Jack Adams had Grace Moore, the Roth String Quartet as some of his artists. He thought he could handle the chorus, so we agreed to put on this concert in Carnegie Hall and J. P. Stevens put up the money for the concert.

Margaret Bullock:

J. P. Stevens, senior, Pete's mother and father.

Lewis S. Bullock:

Finally, our wildest dreams came true, because I was telling the chorus way back in the beginning, “You know, sometime, we might even sing in Carnegie Hall.” Here we were finally singing in Carnegie Hall, March 8,1947. That was quite a thrilling experience. We got excellent reviews. The New York Times critic wrote, “Shows that American Veterans can hold their own with the Don Cossacks.” Despite that success, Jack Adams wasn't able to book enough concerts to hold a big chorus together. We did sing for Penn State and Ohio State Universities on their concert series and a few other bookings, but he just couldn't give us enough, so we had to go back on our old plan, producing our own concerts. We started in White Plains, N.Y., went through the New

England states and what we would do; we'd spend a week in a city starting on Monday and then we'd sing. Mainly the high schools were the big thing. We'd put on a program for the high school assemblies. We'd tune up on the stage and show them how we vocalized and then sang a few numbers. They loved it, the students, especially the music students. Then we'd give out our free tickets to the students at the school.

Donald R. Lennon:

You still weren't charging admission, you were depending upon donations.

Lewis S. Bullock:

No charge. In the beginning when we'd sing for the Rotary Club, Kiwanis Club, the women's clubs, we'd get sponsors, say five dollars or ten dollars. Then we'd print their names on the programs. That continued for quite a while. Later on we just...just free-will collections. Then we'd give our concert on a Friday night, Saturday night, Sunday matinee and Sunday night. We'd usually give four concerts. Then, on to the next city.

Margaret Bullock:

That usually brought in enough money to pay our bills and to go on to the next city. I held onto the money mighty tight.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not a great deal of job security.

Lewis S. Bullock:

We called it our National Goodwill Tour.

Margaret Bullock:

Some of those cities were absolutely unbelievable, the crowds that turned out. Particularly, I off-hand remember one in Youngstown, OH, the auditorium seated about two thousand and we gave a concert at two o'clock and five o'clock and when we finished the first concert, they were lined up way out, just loads of people lined up

waiting to get into the second. We took enough on those two concerts to carry us for about two weeks.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you determine what town to go to next, what city to go to next?

Lewis S. Bullock:

We had to have a town where they had a auditorium of sufficient size.

Donald R. Lennon:

There's a lot of background investigation and planning that had to go into this to be able to find a city with a sufficient auditorium...

Lewis S. Bullock: