| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #205 | |

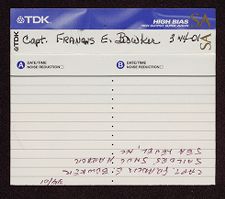

| Francis E. Bowker | |

| 3/14/01 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| Interview conducted by H.A.I. Sugg | |

| Transcribed and edited by William J. Dewan | |

| Edited and proofed by Susan Midgette |

Francis E. Bowker:

. . . Didn't live there long enough to have a place because my father was brought into the World War II business, and went abroad. My mother moved back up to Rutland, Vermont, where she came from. She had lived there until my father came home, and for some time after. Eventually, though, we moved on to Waltham, Massachusetts, where my father was born and brought up. His father was in the stone business, particularly using marble. It came from over in Italy. He did a lot of work with gardens and interior decorations and, you know, old buildings. Some people near me had a great big swimming pool in the middle of their mansion, and he had provided all of the stone for that, for instance. I remember they also had a bathroom in there that was all marble that had come from my grandfather's business. He operated out of Boston. It was named Bowker Street (laughs). I don't know how long they had been there, but it must have been several generations.

The Bowkers had come over in the 1600s, and so had the Chaffees, who were on my mother's side of the family. They both had landed over there in Massachusetts, and

were brought up there, expanded from there. My father, as I said, was born in Waltham, Massachusetts. My mother was born in Vermont. Her family had come over in 1660, I believe it was. So the Bowkers are pretty well Americanized.

H. A. I Sugg:

It would seem so.

Francis E. Bowker:

It would seem so, yeah (laughs). But they spread out all over the country, and I was fortunate enough at a time when I was sailing in the big schooners, to meet a Bowker who had built a ship that I had actually sailed in.

H. A. I Sugg:

Wow.

Francis E. Bowker:

He lived up in Maine. The number of schooners, mostly three-masted, but he built several four-masted schooners. They weren't large vessels--only around five or six tons, mostly. They were good vessels, and they lasted. They seemed to last better than a lot of the bigger ones that were built, because they were running right up until World War II. I enjoyed that life. My father was a college man. He went to Williams College in Massachusetts. He was in the Army during World War II, and when he came back he just never seemed to settle down. I don't know what it was. He went up to Vermont where my mother had gone, and got in the automobile business. That didn't last long. He had various other things that he got into. The worst one and the last thing that really broke him was when he took the family money and he put it into a project down in Cape Cod where they took a big marsh and they opened up an entrance from the sea into this marsh. They planned to build big, expensive summer homes on the land there. And of course, when they opened it up there the harbor was supposed to house their yachts. The place is still going, actually, but when the Depression came my father somehow or other

lost all of his money on that project. And I don't know enough about it; I wasn't told. I was only about ten years old at the time. A lot of it went over my head. The family was very much upset about it, because he had taken the money without actually getting their permission, I guess. Something of that sort.

So I had been going to private schools and that sort of stuff. I finally wound up on my father's chicken farm that he'd started as a hobby, breeding Rhode Island red hens-- superior color and egg-laying. When he died, my mother just got off of the place and went back up to Vermont. So I had time there.

Going to sea was a whole new thing. We used to go down to Cape Cod. My father, as I say, lost his money there, but he always had a liking, and he had a little camp that he and a judge had bought together out on Monomoy Point, which is a point of land that goes from Cape Cod out towards Nantucket. It's an island now, but at that time you could drive down an eleven-mile stretch of it through the sand.

H. A. I Sugg:

How do you spell that name of that place?

Francis E. Bowker:

M-O-N-O-M-O-Y.

H. A. I Sugg:

Thank you sir. Our students who transcribe these things aren't always familiar with the place names.

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah, well, they wouldn't be with that one (laughs). But now it's an island, because the hurricane of . . . '42, was it?

H. A. I Sugg:

There was a big one in '38 that really pasted New England.

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah. Well, that was the one that tore it up. It opened a space there between, so now it's Monomoy Island instead of Monomoy Point. The people who lived out there

were given permission by the government to live in the houses they had built there until they died. And then it reverted to the government. And it's a great place for wild animals and fishing. I don't know whether they still allow any fishing out there, but at the time we went down there we'd go down to hunt birds in the fall, the ducks. If the wind was right, you could right on the beach there and just shoot them down. We would go down there and shoot maybe twenty ducks and bring them home. But there were other people that would come down, and they would shoot all day long, take a dozen birds, and leave the rest of them on the beach, dead. Disgusting.

H. A. I Sugg:

Yes.

Francis E. Bowker:

But we didn't operate that way at all. There wasn't much you could do about it. And then the tankers would come by, and they would be cleaning their tanks as they went by. The birds would get into all this grease and stuff, and come ashore just plastered with black grease. They would die on the beach there.

When my father lost his money, we lived in several different homes. I guess he couldn't pay the rent or something. So we moved from one place to another. We finally settled on the farm, and lived there until my father died. That was about an eighty-acre farm-a lovely place. He wanted to develop it into housing; I was entirely against it. A couple of times there he tried to get me to come back off the sea and help him develop the farm, and I told him I never wanted to see it developed. Well, my wish came true, because after my father died, a man--I believe he was an Englishman--bought the place, and he and some other citizens of the town got together and they made it into an open space. Legal, open space, and nothing could have suited me better. I thought it was a

wonderful thing to have happen. I loved that farm; there was good hunting, good fishing, on it. Well, the fishing wasn't too much, but there was a brook that went down where you could get trout and other fish out of it. But I didn't want to spend my life there. So I went to sea.

As soon as my father died, my mother moved right off the place and practically gave it away-I think it was pretty well indebted. She moved back up to Vermont. So I went off on my ships with her permission. She was not against my going to sea in the first place. Her family lived up there in Vermont and my grandfather was in various businesses. They had a big place down there--I think I mentioned it--where they made machinery for the marble industry. They weren't too far away from West Rutland, where they had wonderful marble. Let's see . . . what else could I say about it?

H. A. I Sugg:

Well, how did you first get interested in going to sea?

Francis E. Bowker:

When we used to go down there at first, I would love to see the schooners going by. And I had a big telescope my grandfather had left, and I would take it down on the beach at Monomoy. That's when we had the camp there. Off on the outer side of it there was . . . it was all sand, of course, but there was a telephone pole out there. The sand had grown right up around it, until there was only about five feet of pole left. And it had one of those little things that they put the glass . . .

H. A. I Sugg:

Insulators?

Francis E. Bowker:

. . . insulator that the wire went through. The glass was gone, and there was just a little, thin (platform) that I could lay my long telescope on and watch the schooners going by. I was there by the hour. Of course, there were other ships that went by, and I looked

at them all. But the schooners were my favorite. I learned to know them as they came by, and when the chance came when I went to sea, I would be passing a ship there, and I'd see one in the distance and say, "That's the so-and-so. I remember her." And this picture up here--you see with the young boy? Well, that was given to me by a friend because he knows about my obsession (laughs). He's still around, and I sent him a copy of this thing that I have.

H. A. I Sugg:

The list of schooners?

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah, the list of schooners. Oh, I sent him a copy of this; that was it.

H. A. I Sugg:

What was your first ship?

Francis E. Bowker:

The first ship I sailed in was the . . . on a trip with some sea scouts out of Boston. East Boston. I looked in the paper, and I saw that a Canadian schooner had come in. It was early in the season, and she was the first one that had arrived with lumber. She was discharging over in Charles Town. So I handed my bag of goodies--coals and whatever I was taking with me--to one of the kids, and I said, "Bring that down, and I'll join you later." So I went over to where the ship was discharging, over in Charles Town. I got talking to the captain--he was up on the top of the ? house there, running the engine to hoist the stuff out. She was only a small schooner, only about 250 tons or so. Let me check here . . . 203 tons. A small three master. And the captain, Hilt Ogilvie, he was her master. She came from Parrsboro, Nova Scotia, which is way up in the Bay of Fundy. So I got talking to him, and he said, "Well, why don't you come aboard there? We can talk better." So after a few minutes there, it got time to go down and have some coffee, and the crew came up to get a twenty minute or half hour rest, or whatever it was. So I

went down in the cabin, and he said, "You don't want to go on these old things. You want to go to sea in steam, where there's some future." I said, "I want to go to sea in sail. I don't care about the future; I'll work that out later." So we had quite a talk. Finally, he said, "Well, I could take you along. I have taken a couple other young fellows along with me." Then he said, "I can't afford to pay you. You'll have to work some." I said, "That's fine, that's just exactly what I want."

So I helped him finish unloading . . . oh, I had to go home and tell my parents about it. My father said, "No, you can't go." Well, that night I guess there must have been an argument upstairs, and the next morning my mother said, "I'm driving you into Boston to meet this captain, and if I like him you can go!" (laughs) Anyhow, I got a little bit of gear together, and I went down and helped them unload. We sailed away for Parrsboro.

We got down there, and they didn't have a cargo for her. So he said, "You can stay aboard the schooner there until we get a charter, or else you can pay your way and go home." I said, "No, I'll go down there. I'll work on the ship if you've got something to do, or that I can do." And he went home, and about an hour or so later he came back down and said, "My mother says that boy can't live on that ship alone. He'd better come up to the house." (laughs) So I stayed with them for about a week or so, I guess.

They finally got another charter, and I had all sorts of adventures. I met the local people and talked to them. Then, off we went. Well, we loaded, I think it was in four different ports, which was ideal for me because most of these things would go down the east, they'd go up into some little guzzle or hole where they had a lumbering mill, they'd

load, and that's all you would ever see on that trip of Nova Scotia. Well, we loaded in four different towns. So I really had a chance to get to know some people, and learn a little about the ship and handling the cargo and the sails. I learned to go aloft and shift over topsail, and what not. When we signed on in Boston, we had to go to the British consul because Canada was under Great Britain at the time. So we went up there, and the consul made out the papers for me. He said to the captain, "What are you going to pay the lad?" He scratched his head and said, "Oh, I guess twenty-five cents." He said, "What do you mean, in an hour? In a day? What?" He said, "No, for the trip." (laughs) So we were gone for five weeks! I made five cents a week pay! (laughs) So that was my introduction to sea going. I had my little touches of seasickness, but I lived through it, and came back. From then on, the sea was really mine.

When I got back home--this was in the summertime, and I hadn't been home more than about a week--the New York Times had a big article about a five-masted schooner that was loading right on the waterfront in New York. She was taking a load of all sorts of automobiles, machinery, and everything else down to South America. There was a steam ship strike going on, and they were loading because they weren't striking; they didn't have any union people aboard the ship and, as a matter of fact, I talked to the captain, the owner, and he gave me a letter. I waited until the ship came in from that trip. I didn't bother to go down because over 450 people applied to go on that ship, and some of them offered big money to go on it, but the owner said, "No, we've got a crew." And the captain was all in favor of that - he didn't want these people. So off they went. I read in the paper along about January that the ship had arrived in Florida. Then I got in

touch with the owner - I went up to his office, and I introduced myself. As I walked up the stairs, I saw two men coming out of an office. It was Captain Faust (sp.?) and a captain of another four-masted schooner that he owned. So as I came up, he looked at me, and Captain Faust (sp.?) said, "Well, what can I do for you, young fellow?" I said, "I want to ship in the EDNA HOYT." He gave the other captain a jab in the ribs, and they started laughing. He said, "What makes you think you can ship in the EDNA HOYT? We turned down over 400 people last summer that wanted to go in her and offered to pay us money! What are you going to pay?" I said, "I don't have any money." He said, "Well, what made you think that I would take you?" I said, "Well, I figured I would come up here when you didn't have anybody else and I could talk to you, and that you would hire me." He said, "Hire you? I guess I could do something about that. Come in and see me later on, along about March or April. The ship ought to be coming up to Florida with a cargo of goat manure, and then she's gonna load lumber for New York and Portland, Maine."

So I went in to see him, and he made out the papers, and he told his wife to write a letter to the captain saying that I was coming down. She brought in the letter, and he said, "Look this over. What do you think about it?" I said, "Well, it doesn't say anything about pay." He said, "Pay! You want pay?" I said, "Yeah." He said, "I had people offering me thousands of dollars to go on the ship!" I said, "Yes sir, if I'm going to sea I want to get paid wages for it."

Well, he sent it back in, and had his secretary rewire it there, and I was to get twenty-five dollars a month. That was the going pay at that time in schooners.

H. A. I Sugg:

What year was this?

Francis E. Bowker:

This was in July of 1935. I went home, and I bought some stuff that I could wear, seagoing stuff. And I got on a bus and I started down. I went to New York, and I spent a night with an uncle of mine that lived in the old topside of the big hotel facing Central Park. He was in the business of . . . let's see, he had a business . . . oh, milking machines. He had the first milking-machines that were made, and had a patent on it. He lived in this big place in luxury.

H. A. I Sugg:

I'm trying to remember the names of those first ones that came out.

Francis E. Bowker:

I can't remember it either. But anyhow, he made a fortune. So I put up with him. The next day I was starting out, and the handle fell off my suitcase (laughs). So he gave me a new suitcase to bring down. Then I stopped up at another ? place down in Baltimore. I went to Annapolis to see the graduation over there, which was quite a deal, you know. Everybody throwing their hats up and everything at the end.

I wasn't in any rush to go down because I knew the ship wasn't getting loaded very fast. I finally got down there in the middle of the night; the bus had broken down. We didn't get there until midnight, so I put up in a ? hotel overnight.

H. A. I Sugg:

What town was this?

Francis E. Bowker:

That was in . . .

H. A. I Sugg:

Miami?

Francis E. Bowker:

Not Miami. Up the river there. Jacksonville. And we would take the lumber up to Weehawken, New Jersey, and Portland. So the captain met me when I came down. It was on a Sunday. I came down in the morning, and there was nobody in sight. So I said,

"Well, I'll wait until the afternoon." They had a nice big clouding (??) over, and I got pictures that show her. She had a long ? that went up two masts, and then it dropped down into the well deck (?). They had an awning up there, and there were three people sitting under the awning. Two of them had on high pressure (?) officers' caps; the other was a lady. So I walked up the gangway, started aft. All of a sudden, one of these men got up, put one hand on the rail, and the other on the side of the house, and said, "You're not going any farther. What can I do for you, young fellow?" I said, "Well, I have papers from Captain Faust (sp.?) coming in and signing me on as an ordinary seaman." I handed him the letter that the captain had given me. He picked it up, he read it, he folded it, and handed it back to me. He said, "You know what you can do with this goddamn thing?" He said, "You put it back in your damn pocket and get your tail down that gangway right off!" I stood there dumbfounded, and I said, "Well, captain, I'm going to tell you something. It cost me money to come down here. I had to pay for my own transportation. I had to pay for my meals. I put up in a hotel overnight in one place." I didn't tell him it was my uncle's place! (laughs) I said, "It's gonna cost me about the same amount of money to go home. If you want to take care of those charges, I'll go." He said, "That's the way it is?" I said, "Yes sir."

Well, he didn't know what to say for a while! (laughs) He said, "Alright." Then he started asking me questions about seamanship. Well, I'd been on that three-master and I'd studied and read about it; read technical books. So he really didn't have much to go on. He said, "Alright, you be down tomorrow morning at six o'clock ready to turn two." I said, "Captain, I can't do that. I've got some things I have to do in the morning."

(laughs) I didn't have a damn thing to do! I said, "I'll be down tomorrow at noon and ready to turn two at one o'clock." Well, there wasn't much he could say.

So I was down there on time, came up the gangway, and he was waiting for me. He said, "You see that little house up at the other end of the ship?" "Yes sir." He said, "That's where you're gonna be housed. That's where the niggers live." That's the way he put it. He had a black crew. So I said, "Yes sir." And I walked up, and those fellows greeted me with open arms. The galley, instead of being up forward in the ship, was back in the quarterdeck. And the old cook had evidently been there and heard this whole discussion, and went up and talked to the boys about it. (laughs) And those black fellows were great to me. They were great, except for one. A little guy. I hadn't been aboard long, and this little fellow started back aft. The sailor that seemed to be the one I was going to work mostly with, he said, "Now, there's one thing I want to tell you. You see that little fellow that just walked aft? He's going back to the captain. Never say anything in front of Little Joey that you don't want the captain to hear." And that man was so good to me, teaching me. And if I made a mistake, he'd call me over in a corner somewhere and say, "Now look, that's not the way we do it." And he'd tell me how. I thought the world of him. He was a great big fellow, but he had no toes. He'd frozen them off up in the Arctic. He walked rather strangely (laughs), but he was a wonderful man.

We got up to New York, and we started unloading the deck load. The crew went up to him to get a little pay to take ashore, you know, to get a drink or two. Well, I decided I'd go back and get a little, too. He said, "That's fine. I'm going to give you

what pay you have coming, and you can get the hell off this ship." I said, "Captain, I'm signed on to go to Portland." I said, "I intend to go to Portland on this ship." Well, he gave me the money, and I went up with the boys and I guess I had a drink, I don't know. Back on, we unloaded half the cargo, and the rest of it was to go up to Searsport. Or was it Portland. Yeah, to Portland. That's right. We went to Weehawken, New Jersey first, and then to Portland. My mother came down to pick me up, so I took her back and introduced her to the captain. He said, "You ought to tell this boy never to go to sea again. He doesn't belong on a ship like this." Well, mother had a little chat with him, and off we went.

The next year, he came up to Boston, directly from the south with a cargo of goat manure. That was a regular trade.

H. A. I Sugg:

Where was that from?

Francis E. Bowker:

It was from Venezuela. I had shipped on a little three-master, but I never sailed it, and the ? paid off because they sold the ship to the Portuguese. She was going into that run. So we both went down to see the EDNA HOYT and we both decided . . . the captain said he'd ship both of us. Well, the other guy that was going on ship was boatswain. But I had to be an ordinary seaman. He was an experienced man in steam, and he'd gone to a very prestigious school down near Cape Cod, and had loads of money. I didn't know about that at the time. So we got to this place there where we were going to unload, and he came up to me and said, "Say, are you going ashore tonight?" I said, "Yes." He said, "Are you going to have a beer?" I said, "Yes." He said, "Well, I'll tell you something. I don't have anybody I can go ashore with. The mate is too high hat, and

so is the captain. If you will come ashore with me, once we hit that dock, we're even." He said, "When you get back on the ship, call me sir if you want." (laughs) We sailed in several ships together. He was friendly-he was the mate, and I was the boatswain. By that time, I had a mate's license, but he had the job, so I was the second mate or boatswain. He was a great guy. And I sailed in several ships with him. Then the war came along, and I don't know why he did it, but he joined the Navy.

H. A. I Sugg:

Laughs

Francis E. Bowker:

The first trip out, he went across the Pacific, and something carried away up in the forward of the vessel. And he took two men and went up forward to clear it, and she took a dive, and he went right over the side. And they couldn't pick him up. I don't know whether he got hit in the head or something when he went, or what happened. So that was the end of Bob Robinson.

H. A. I Sugg:

What's his name? Bob . . .

Francis E. Bowker:

Robinson. I don't know whether he was . . . I can't discuss that part of it, I guess. But I found out that he had several million dollars. He went to sea because he wanted to do it. Now he wasn't the only one I ever heard of that did that. Really rich boys that went on boats were mostly on steamers, but he was quite a guy. He had two aunts that he lived with, and that's why I think he was illegitimate. Anyhow, I used to call on them, and then one after the other, they died. I came in one trip--one of them had already died--and I knocked on the door, and the maid came. She said, "I'm sorry to tell you, but Ms. So-and-So just died about five days ago." I said, "Oh, that's too bad. Well I'll leave." She said, "No, I'd like to talk to you." So I went in. She said, "Did you know that your

friend was a millionaire?" I said, "What?!" (laughs) She said, "A millionaire!" I said, "Well, I knew he had more money than I did, but I didn't know that." She said, "I got in touch with his uncle," who I'm sure was his father. "He came down and went through Ms. So-and-So's room. And she never allowed me into the room, or anybody else into her room. But first we went into the closet there, and we found bags hanging off hooks full of $100,000 dollar bills. We went through the dresser; that was full of more. We went to the bank, and that was full of uncut gems." (laughs) Poor Bob left a lot behind him.

One thing I did several years later, I got in touch with his father, I think it was, who had an office in Boston. And I told him I'd like to see him. He said, "What about?" I said, "About his pictures." He said, "Well, what is it about his pictures?" I said, "Are they anything that you really want?" He said, "No." I said, "Well, Bob and I were good shipmates and friends, and I have a collection of sailing ship pictures, and I was just wondering if it might be possible to get those pictures." He said, "Well, come on in." So my wife and I drove up to Boston, and I went up to his office and walked in. The girl at the desk went into another room, and she came out and said, "He'll talk to you, but you'll have to go out in the hall." So he came out, and he said, "Now, just what is it you want?" I said, "The only thing I want, sir, if you don't need them, are Bob's photographs." "Oh, is that all you want?" I said, "Yes." He said, "Oh, sure. I'd be glad to send them up to you." But I think he thought that I was up there to try and get money out of him.

H. A. I Sugg:

Yeah, sounds like it.

Francis E. Bowker:

That was my impression of it. I never heard from him again. I've got the pictures in my book; some of them. And Bob was a wonderful shipmate. But that was the end of that one. Then I went on to the other one.

H. A. I Sugg:

Did you run into any big storms or anything during this time?

Francis E. Bowker:

I was very fortunate in that I was in these vessels. Yes, we ran into the edge of some hurricanes, but we never got into the center of one. By that time, of course, they had radios aboard the ship. They didn't have any transmitting radios, but the captains all had one to listen to the weather reports on. And so we could book (?) our way out to the edge and avoid the center of the storm.

H. A. I Sugg:

So you always got the edge of the storm. That was fortunate.

Francis E. Bowker:

It was. Well, of course, we'd take a beating, and I've got some photographs. Bob took some, and I think I took some. I always carried a camera with me. So they're mixed up in the books here. I collected them from other shipmates as well. That guy got one, it's just of the EDNA HOYT. Let's see, was it the EDNA HOYT? It's this one here.

H. A. I Sugg:

We were talking about storms, I believe.

Francis E. Bowker:

There were storms, and there were storms. Of course, we had a lot of fog to contend with. The fog there, especially off this area here, would be coming down in the cold waters, and then it would hit the Gulf Stream coming up, and that's always been a hazardous place to be.

H. A. I Sugg:

Especially for sailing ships.

Francis E. Bowker:

For sailing ships, yeah. You'd come down through the cold water, and then if you were down really far south you'd head out and get across the Gulf Stream, and then go

down by the Bahamas, then cut in again. That was the general way to do it, if you were going into Florida, for instance. If you were going offshore, of course, you would get out and go by way of Bermuda. That could be a funny trip too, because you'd get down into the doldrums there. Sometimes it might take you ten days to go two hundred miles. You'd get a little breeze up, you know, and it would die out, and she'd begin to roll, and you'd lower the sails, a slat apart. There's always something to do on a sailing vessel. And you didn't want your sails slating, and so down they'd come.

Well, the war had started by the last trip I made in a big schooner. That was the RAWDING. We'd get down there, and we'd slat around. We got pretty well down, and we saw smoke on the horizon one day. We were just, as I say, just dawdling away. Airplanes started flying all over us. The first day a couple of planes came in the morning, and then in the afternoon two more came around and had their machine guns - on top of the plane in those days. And they would have the machine gun trained on us as we went by them. What the heck is this all about? So, it went on for three or four days, and all of a sudden we saw smoke on the horizon. Up came an airplane carrier, a cruiser, and two destroyers. So they went down five miles below us, and one of the destroyers turned off, came around, swung up around us, came up, dropped a boat in the water, took off in a hurry. The boat came over alongside there, and they all came up with machine guns pointed at us. "Get over there by the rail, you guys! Get over there by the rail!" (laughs) Well, we didn't know what it was all about, of course! So there were two officers aboard, and they went down below with the captain and the mate. They had a little discussion. Pretty soon they came up, and the leader of the two there said to the captain,

"Well, now I have to go down below there and look in your hold." Casey said, "You don't want to do that. That's pretty dusty coal they've got down there." "Well," he said, "I've got to do it. We're going down." So we took off the hatch cover and down they went. Well, they came up-the second in charge there was breaking himself up. He said, "Thank God. When I get back I'm going to sue the United States Navy!" (laughs)

Anyhow, we were all clear then, once they realized we were an American ship and we weren't doing anything naughty. (laughs) But you see, their idea was that we might be loaded with torpedoes to load up the submarines, which they'd use them on ships coming up. That was the whole story.

H. A. I Sugg:

Interesting. The Germans did have “motherships” of the sort.

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah, they did.

H. A. I Sugg:

Obviously, a sailing ship would look strange.

Francis E. Bowker:

Well, of course there were sailing ships around, you know? They didn't understand why we weren't going somewhere. (laughs) I think we took that load down to . . . Martinique. There was another schooner that went to Martinique with us. And then we got down a load of goat manure. The other ship came in after we did. And they wouldn't unload us until he had unloaded, because he had started first, and he was supposed to be unloaded first. But whether he ever came in or not I don't know. (laughs) Strange . . . Frenchmen are that way. Anyhow, we had to wait. Then we got down there, and we found the other vessels laying there in anchor. Nothing was being done. Well, the captain had never made a foreign voyage like that before, and he'd always just been

coasting up and down this coast here. He used to come down here and bring lumber down, and then he'd load . . .

H. A. I Sugg:

. . . the cargo. Lumber and . . .

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah, so goat manure went primarily to Jacksonville and Boston. The lumber we'd take up, might go to New York or most anywhere. So it was a busy life. And those old schooners lasted right up until the end. But most of the big four-masters were weighed up, because after the big Florida boom all the sailing ships had business. After that, the steam was taking over. Most or a lot of them were laid up in the creeks and some of them were sunk for insurance. Some of them were set on fire, but there were a few of them that existed right up until the end of World War II.

H. A. I Sugg:

Are there any of them still afloat that you know of?

Francis E. Bowker:

No.

H. A. I Sugg:

They haven't been resurrected like the tall ships?

Francis E. Bowker:

No, no.

H. A. I Sugg:

Well, this was at the beginning of the war. What did you do then?

Francis E. Bowker:

Well, then I went in steam. The first ship I was in was the tanker DURANGO. I only made one trip in her, and I had a fight with the union fellow there. He told me I'd better get the hell off the ship before they killed me. I think they tried to. I was down cleaning a tank, and they left me there. The gas was getting me; I couldn't even hold a hose anymore. I was backed up against the baffle (?) there. I was holding it and getting weaker and weaker all the time. Finally, this guy came down and asked, "Think you can get up that ladder?" I said, "Well, I'll try." I wasn't about to fight with him. (laughs) I

got up the ladder and I hit the fresh air. So then I had gas coming up all through my system, and the captain said, "Look, you're not going down there again. They can clean the tanks themselves." He said, "I see you've got a sail kit with you." I said, "Yes." He said, "I've got an awning up on the bridge there that needs some repairing. I'll let you do that instead of working down in the hole." He was a pretty decent guy, but I know that union fellow was trying to teach me a lesson or kill me, one or the other.

H. A. I Sugg:

Well, probably doesn't make much difference.

Francis E. Bowker:

No. So then I went to another union. Of course, I had to be on a union ship, and I sailed on her for eight months. And, well, we went everywhere. Of course, the war was on.

H. A. I Sugg:

What ship was that?

Francis E. Bowker:

That was the ALTAIR. ALTAIR was the second one.

H. A. I Sugg:

ALTAIR?

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah. I joined her on April 16th, and left on November 16th.

H. A. I Sugg:

1942?

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah, 1942. And that was a rough year out there, I tell you.

H. A. I Sugg:

Was that in the Atlantic or the Pacific?

Francis E. Bowker:

No. So then I went to another union. Of course, I had to be on a union ship, and I sailed on her for eight months. And, well, we went everywhere. Of course, the war was on.

going north of that shoal; I'm going south of it." So we went south of it. Early in the morning, just about seven o'clock, bright daylight, there was a tanker coming out, and we were just about opposite of Ship Shoal at the time, and all of the sudden that ship just burst into flames from one end to the other. I don't thinking anybody lived off that ship. She evidently had high-test aviation gas or something like that in her. But we put the old thing right full speed ahead. She was humping up there, so you could stand back in the poop, and you can see the bridge rise up. Then the bridge would go down, and you'd see the bow. (laughs) That's how flexible she was.

We got to the mouth of the river going up to . . . I forget the name of it now. But two tugboats met us at the mouth of the river, and they towed us up the river. We went right into the first dry dock there was. They already had it down in the water and ready for us, all blocked up! We had about three weeks in there while they made repairs. We had to have work done on it three times, as I remember. On the last trip, we ran up to Boston, and they put it into dry dock and paid us all off, because they didn't know whether she'd be going back to sea or not. I guess she probably did. In wartime, almost anything would go that could float. But that was the end of my time in steam.

H. A. I Sugg:

You went ashore about at the end of the war, did you?

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah. In 1942 I went into the CARROLLTON, which was a laker, after that. But she never sailed. They sent us up to Quebec to bring her down, and they had three ships up there that they'd set up to come down south to go on the sulfur trade, bring sulfur up. Two of them sailed out, and they had not done anything to prepare them for saltwater. So their engines broke down, and one of them drifted ashore, and the other one got wrecked

off of Newfoundland. Got in the ice, and drifted in with the ice, I guess. The one that I was on was frozen in about five or six feet of ice in the harbor, and they decided that they weren't going to send that one out. But they were going to find out what the heck was going on. Well, they found out that practically nothing had been done; the lifeboat hadn't even been fixed up and loaded, and other things hadn't been done. So they tied the ship up to have an investigation, and sent us home. That was when I went to officers' school. I sent a letter there . . . oh, it was right near Mystic, what's the name of the town . . .

H. A. I Sugg:

New London?

Francis E. Bowker:

New London, yeah. I got a letter back saying that I wasn't qualified. Well, I took a trip right down just as fast as I could to the school. I walked in, and this young fellow said, "You're not qualified. You've got a sailing ship time." I said, "That's the best time you can have as you're going to sea, you damn fool!" And just then I heard a voice behind me. "What's going on here?" There was an admiral standing behind me. I said, "This goddamn fool doesn't think the time of sailors is a good time to get a license to go in steam!" He said, "Let me see your papers." He looked at them and said, "You sign this guy up immediately!" So that was where I got my third mate's sticker.

H. A. I Sugg:

Sailing school is certainly the best school I know of. And I'm a steam ship, but I've done some sailing. I can remember up in Pearl Harbor, with that tradewind blowing there, if you were in a destroyer, you had to sail the damn thing. Most Navys have sailing school ships.

Francis E. Bowker:

Well, I had another wonderful thing happen at that school. I had a friend who came from Maine, and he had a wife that worked in an office in Boston. He said, "Come

on up to Boston with me for a bit." I said, "No, I've got plenty to do here in the school." So I put him off a couple of times, but finally I said, "Alright, I'll go up with you." He said, "I'll get you a girlfriend." Well, he would get his wife to get me a girlfriend. He was a spendthrift. He'd go up and he'd gamble and lose all his money, and then he'd have to borrow money to get up to Boston. (laughs) Hell of a nice guy.

This time I said, "Now, look. You give me my money, and you keep the hell out of that place." He said, "I'm going in. I want some money." I said, "Here's ten dollars. When you spend that ten dollars you're done until we get to Boston, and then you can take your wife out and do something." So we got up there, and we stopped at a little bar on our wait until they got out of work. We were just drinking our first drink when the two girls came down. The one that his wife had gotten ready for me, she didn't want to come, so he picked out another one. So we sat there, and then we went out. We went uptown. It was a hell of a night, it was slushy, great big puddles in the road. It was a terrible night. We went up to a nice restaurant and had supper. I don't know whether we went to a show or not. Anyhow, we got back. My [future] wife was going to take a train to get back, I guess. It stopped right near where she lived. So I was going to say goodbye to her, and she said, "Aren't you going to come with me?" I said, "Well, yeah." She said, "Well, I thought you would be gentleman enough to come along with me."

H. A. I Sugg:

Laughs

Francis E. Bowker:

So we got to her house, and she lived on the third floor of an apartment home. I was going to leave her at the door, but she said, "Well, come on up and meet my mother." So I went up and met her mother, and then I went out and got a taxi and I came back

down. We were going to meet again the next day. I rented a room there, and I thought I'd be able to get her into the room the next night. (laughs) The whole goal. So I went up there--whether it was the next week or not, I think it was the next week--and we just had a nice time, nothing else. She said, "I won't be able to see you next week. I've got to go out to the Midwest near Chicago." I didn't know what it was all about. So she went out the following week ? . Went up to Boston, and I think I'd already asked her to marry me, and she said she couldn't. What she went out there for was to tell her other boyfriend's mother that she was not going to marry him, because the mother was in the real estate business. She'd bought a house for her, and she was getting it all completely furnished. And Carol said, "No, I couldn't do that." She said, "I wouldn't be my own boss. She would be in that house all the time, and she would be telling me what to do." So she said, "I'll marry you." (laughs)

So we did. The week after I graduated, we were married. The whole family came, or those that could because of the wartime.

H. A. I Sugg:

When did you graduate?

Francis E. Bowker:

In 1941, it was. Before I left on my first foreign trip, I'd gotten her pregnant. (laughs) I only had about a week to do it, but I did it. (laughs) Her mother was madder than hell. She said, "I've got to watch every day and see if the baby comes out."

H. A. I Sugg:

When you graduated from there, what did you have, a mate's license?

Francis E. Bowker:

Uh, third mate. That's as far as I got because I went in the DURANGO, the ALTAIR, and I was on that stupid thing, the CARROLLTON, that didn't go anywhere. Then I was on the SS GEORGE WASHINGTON, which was a passenger ship that

belonged to the Eastern Steamship Company, a rich man by the name of ? had bought it. And we took various trips to Newfoundland, the West Indies, Bermuda, and other places. Then the next trip was the ALCOA CUTTER . . . well, I left her. I didn't like the stench of puke coming up through the ventilators up onto the flying bridge, and, oh gee, I hated it. So I said, "I'm going to get off onto something that doesn't carry passengers." And then I went into the ALCOA CUTTER. The ALCOA CUTTER was the one I got sick on, and came up to go on watch. Everybody had been sick. The captain had left the ship and stayed in a hotel in the next city until we left. The mate stayed in his room all day long, and only came out for meals. The second mate and I had the whole ship on our hands, and I guess the tension of that had a lot to do with what happened to me. We all had the flu, to some extent. And we got going back home, and we ran into a terrific gale, right out of the west.-somewhere halfway across. And I got up to go on watch one night. I went into the bathroom, and the next thing I knew I had blood coming out of both ends of me. I felt faint and I called the second mate. I said, "You're gonna have to take my watch or get someone else." "What's the matter?" I said, "Just go on ahead and look at the deck there. It's covered with blood." I crawled into my bunk, and I don't know, I think it was probably two or three days later, they got the convoy somewhat put together. You see, there were only, I'd say, eight or nine of us left in the convoy, and the rest were scattered all over. Evidently, they gotten enough put back together so that they had a port. I don't know if it's ten or twenty miles from St. John's to Newfoundland. I think it was probably somewhere around that, and I heard the doctor when he got aboard. He was talking to his assistant, and he said, "You know, I don't

think this fellow is going to make it to New York." And the assistant said, "Gee, it doesn't look that way, doctor." He said, "I'm gonna see if I can't get the captain to take the ship into St. John's, get it an escort, take us into St. John's and get this fellow to a hospital." "Geez, Doc," he said, "I've never heard of a ship leaving a convoy to bring a sick man in." "Well," he said, "Don't you remember Dottie (?) and Mable, [whom] we met during the last time we were in?" "Yeah." "Wouldn't you like to see them again?" "Geez, Doc," he said, "If you can do that I'm all for it!" (laughs) They used to tell that to the women when they'd meet them down there when I had my display at the museum, and every one of them would get the funniest grin on their faces. (laughs) But anyhow, they saved my life. I was in the hospital for a long time. A month in the hospital in St. John's, and then they shipped me down to New York, and I was in the hospital there.

H. A. I Sugg:

Ripley?

Francis E. Bowker:

The seaman's hospital out there on the island . . . Staten Island. Seaman's Hospital there. I was there for another six weeks. My wife came down with her mother a couple of times. Finally, a guy told me, "Look, you ought to get out of here. I've got the same thing you have, but I'm getting a bit better. I'm going up to Boston, and I'm going to the Lahey Clinic. You ought to do the same thing." So as soon as I was able, I got out of there, and I met my wife up in a hotel in New York near the railroad station. And she came down to meet me. What happened was, the doctor wasn't going to get me my gear. I said, "You get me my gear, and I'm going." He said, "I'll get you arrested! If that's the way you feel about it, go! I'll give you a month's leave of absence, and then you're on your own." So I took my suitcase, and I had a big sea bag about that high that I made

myself, and I dragged it from one end of the ferryboat to the other. I was too damn proud to ask somebody to give me a hand. I got off the ferryboat, and just by the grace of God, a taxi stopped right in front of me and let some people out of it. He looked at me and said, "Want a ride?" I said, "Yes, sir." So I got into the cab and I dragged my stuff with me. Another fellow came along and tried to get in the other side, and he said, "Get out of here. I've got a fare." The guy said, "Where are you going?" And he told him, and the guy said, "I'm just going halfway up there, right on the same road." So the driver said, "Do you mind if he comes?" I said, "No, just let's get going!" So he rolled up with us halfway, and we got to the hospital.

There was a stream of men, all in black suits, you know, businessmen. They were going up to the counter. There were two clerks there, and one of them was saying, "Fellow, you've got your reservation?" "No, but my owners (?) said that you'd be glad to help me out." He said, "Captain, we're full; we haven't got any rooms." Here I am listening to this, you know, and half dead. Finally, I got my nerve up. I walked up to the counter, and leaned up against it, and said, "I've been listening to what's going on, and I don't have any reservation. Is there any way you can get a mattress or a cot or something, and put it in a closet somewhere just so I can lie down?" He looked at me and said, "What do you want? A single or a double?" I got the double. (laughs) We stayed there about three days. So, sometimes things do work in your favor. I never forgot that fellow, that clerk. Of course, he probably expected me to leave the next day, but I couldn't-- the goddamn boaters (?) wouldn't send my pay from over the other side of the

river. I had to go over myself to pick it up from their office on the New Jersey side. They wouldn't send it over to me. I had to stagger in there.

They were having a conference there with the captain and the mate of that passenger ship I had been on before I went on the other one. I got word that the captain wanted to see me, because I kind of walked away from the ship without telling him I was going. The officer I was talking to said, "You don't want to see him." (laughs) So I got my money, and we got home. I went to the ? and they said, "No more. Go until someone asks you what an oar is, and get a job." My family had a big business--I guess I told you about that--up in Vermont. Then I got to Sea Scouting.

H. A. I Sugg:

Yes. How did you get into that?

Francis E. Bowker:

Well, I was working for the family business . . . no, I had my own business at the time. I was selling stuff to town clerks. My wife was quite interested in scouting; my daughter was in scouting; my son was in scouting. They had just started the scouting thing for boys up there, so they asked me if I would come in and work with them. So I got my own scout troop, and I hadn't been in it more than three months, and I got a call from another town. They had a scout group out there. He said, "I have a wonderful opportunity. I tried to get a trip on the schooner ? down at Mystic seaport. They said they were all full, but they said that if there was an opening, they'd let me know." He said, "I just got the opening; I've got somebody that can go." He was crippled; he couldn't go. He said, "I've got a fellow to take the boys, and I've got four boys that can go." He said, "Can you get any together?" I said, "What is this schooner?" He said, "It's supposed to be the finest schooner ever built." I said, "Well, that's taking in a lot of

territory." I said, "I'm going down to see this boat, and see what it's like." So I drove down with my son, and I got down there. The schooner was tied to the dock, and she was beautiful. There she is (showing picture). All built of teak and bronze. Her whole hull was teak.

H. A. I Sugg:

A three-master?

Francis E. Bowker:

No, just two masts. It was only sixty-two feet long. And she can sail. She went over with the ships that went to Europe this fall. And she wound up in Antigua. The captain came home for a month to get a rest (laughs). One group of kids after another. Each part they went to they got another six boys and girls. They had both boys and girls. They were the crew. There were ten people aboard all together. They had a cook and a mate, of course. I think they had a doctor aboard the whole trip. So that made up the whole number of twelve people. They won the race across on time by something like ten or twelve minutes. Then they went on their own, and they went to Spain and Portugal, and I think they went to France, too. Then they went down to the islands down below the Azores there. I can't think of the name of the island they went to.

H. A. I Sugg:

The Canaries?

Francis E. Bowker:

Well, down that area. And they stayed there for a couple of weeks, and then they came across and went to Antigua. They got to Antigua, and he had had enough. So he came up home, and spent a month there. Then went back. And the last I know, he was sailing around the islands and he ought to be on his way up home very shortly. He wanted the weather to be halfway decent going back home. So he may be in Mystic right now, but based on the way . . . I suggested he ought to stop into Beaufort because I'd like

to see the old schooner (laughs). He said, "No, we're gonna go the fastest we can. I want to get home and get ready for the next season." So this year, they'll be doing the regular weekly type of trip. Or something along that line.

H. A. I Sugg:

How long were you in the bridge?

Francis E. Bowker:

Twenty-five years. I was mate for three years. First the mate left, and he was the one to convince me to come aboard and take his place. And then the next year, the captain left. Then I had the ship. The captain didn't like it. He was getting to be a drunk, too. It was a good thing he left, because the ship was not being taken care of properly. So then when I got ahold of it, I got this fellow . . . he was English. No, he was an American. I don't know how he got over to England . . . Oh yeah, he was going to Annapolis and Annapolis, at the time of the invasion over there in Vietnam or somewhere--people don't know it--but about a dozen of the students at Annapolis walked off and got out. They wouldn't have any part of it. And of course, they all had to get out of the country. First he went to France, then to Canada. Then from there he went to Germany. I think he went to a church school. I'm not sure; he never talked about it at all. But he met a girl there, and he married her. She was a German girl, and they lived right on the worst part of it. The part that we got into, you know, the French and the Germans trying to share it. The girls there were subject to rape, and her family wasn't going to have any of that, and they built an alcove into one of their rooms, and if they heard any noises, she would jump into that alcove. She stayed in the house all the time, and they came in several times, but they never found her. Well, he married her, and then they went to France, and he was headmaster at the boys' school that took in Asiatic boys.

And he did that for three years. He finally left, and he said, "I couldn't stand it. The way they rob those parents. They were good to us, though. They sent us good presents, but they would just rob the school . . . between the school and . . ." Well, I never got the whole story. He didn't like to talk about it. So he came out to this country, and he came up to Mystic for some reason. I didn't meet him in Mystic; I met him in another port. He was introduced to me, and he said he was looking for a ship. And I said, "Send me a resume." So I got back, and I had the resume waiting for me. I looked at it, and I called him up and said, "I don't think this is for you. You're too educated for a job just as mate on a little schooner like this." He said, "Captain, are you going to be in your office tomorrow morning?" I said, "Yes." He said, "I'll be there at nine o'clock." Before he got through with me, he was the mate (laughs). Then he became the captain.

H. A. I Sugg:

What year did you go with the BRILLIANT (??)

Francis E. Bowker:

Let's see . . . 1959. I stayed until '62. I was in there from '62 to '83. And that's when I came here. Well, then I went ashore and did a little work, and left him as captain. That was it. When I hit 65, I figured it was time for me to move along, and have him take over. He's done a wonderful job.

H. A. I Sugg:

These were all scout cruisers?

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah, mostly scouts. Now and again they carried a bunch of older people, but I didn't care too much for that.

H. A. I Sugg:

Where did you go? All around the Caribbean?

Francis E. Bowker:

No, no. They were five-day trips. At first when I went there, they wouldn't let her go outside of the islands there. We had to stay in shore. And then they gave us twelve miles after a while.

H. A. I Sugg:

What was the significance of twelve miles?

Francis E. Bowker:

Well, we could go out to sea. That was the limit.

H. A. I Sugg:

The twelve-mile limit has some international law ramifications.

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah. Then we could go rum-running too, of course (laughs). Which we didn't do. I never did take her out. I took her around a couple of the islands now and again, just to get out of sight of some of the land. But I was really careful about it.

H. A. I Sugg:

The scouts manning the various stations and so forth.

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah. Well, I just had one person. He had to do the cooking, the cleaning . . . and he did everything. Now he has a cook, and he's got everything. It was me and my mate.

H. A. I Sugg:

What did you do, rotate the kids around in various stages?

Francis E. Bowker:

Yeah. Well, at night we'd give them each a two hour stay on lookout, you know? Sometimes I'd get up at night and walk up back aft and the kid would be lying there, "Zzzzzzz." "GET UP! You're supposed to be watching!" (laughs) That would scare the daylights out of them. We carried more Girl Scouts than we did Boy Scouts, actually.

H. A. I Sugg:

When the girl scouts went out would you have female scoutmasters?

Francis E. Bowker:

Oh yes, they had to have at least one. Often they came as two.

[End of Interview]