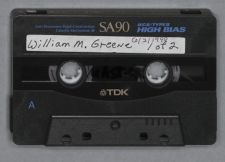

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #178 | |

| Rear Admiral William M. A. Greene, (USN, Ret.) | |

| June 2, 1999 | |

| Interview conducted by Dr. H. A. I. Sugg |

H.A.I. Sugg:

If you would, Bill, start out with a little about where you where born, when and where you went to school, and how you got interested in the Navy. Then, how you came into the Navy.

William M. A. Greene:

I was born in Linville, N.C., Avery County. Linville is in the mountains of North Carolina, near the Tennessee line, up in golf country. I was born on June 17, 1920, in a little place called Bobbin Town.

H.A.I. Sugg:

June the seventeenth, you're just two years younger than I am.

William M. A. Greene:

I was born in Bobbin Town, which is a part of Linville to the south, where a lot of the residents were employees, making bobbins to go to the hosiery mills in Hickory and the Piedmont area. From there, my family moved later on to another residency in Linville; my father being a grocer, but not owning his own business. Then I spent a short time in Elizabeth, Tennessee, where he worked in construction. After that, we went to Jacksonville, Florida, for two years; I was eight at that time. We moved to Jacksonville, because my father became an employee of the Motor Transportation Company as a bus operator, from Jacksonville to Tallahassee and back. On one of his trips, he became seriously ill. It turned out it was a ruptured appendix. In those days they didn't have the antibiotics we enjoy

today, so he went to surgery and did not make it. My mother was with him. At that time, I was age ten. My mother was a little younger than twenty-nine with three children, I being the oldest.

We came back to North Carolina, and she arranged to get us into a school called Crossnore School near Linville. It was a very fine school. Two doctors, Eustace and Mary Martin, founded it. They were both Davidson graduates. (I think she was the only woman to graduate from Davidson in those days, but it happened to be her father was president.) They then went on to Pennsylvania for medical school and wanted to be missionaries. They were unable to get an appointment by choice, so instead they went to the mountains of North Carolina. They said they would be missionaries there for two reasons: one, because the mountain children are not being educated; and second, she wanted to take on the moonshiners, which she did. I'm surprised that she lived through it.

She founded the school, and my mother went there as a housemother. [We], the two boys and one girl, went to separate dormitories peculiar to our age level. They had little boys and girls, middle-sized boys and girls, and big boys and girls; so that's where I grew up. I graduated from high school in 1939 and went on to Brevard Junior College. Brevard is in Transylvania County, which is northwest of Asheville about fifty miles.

That was a fine year. The reason I went there was because of my football coach from Crossnore. He was a Davidson fellow who, as a matter fact, had been the national champion in wrestling, having beaten a West Pointer in the medium weight, which was around the 160-pound area. He also played football at Davidson. He came to Crossnore as a young graduate, and he was one of those people that everybody likes. We called him “Honest John.” He was such a fine person. Character was the name of that gentleman in

my book. Because he went to Brevard, I went over there for my selection for a college. After my one year as a freshman, he was offered a position at East Carolina Teacher's College and off he went. Most of his football team went with him, and they came back and got me. I had not planned to go. I had been elected president of the student body and student council for the next year, which would have been my sophomore year.

Parenthetically, I had had my eyes on the Naval Academy from the time I was in high school and saw a movie called Shipmates Forever. A lot of the Class of 1939 was involved in that movie.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Yes, I was assistant director on that particular one.

William M. A. Greene:

Dick Fowle and Ruby Keeler. Well, when I saw the movie, it caught my interest right away, and somehow I had more interest in football. I was really a little bit of a nut. My mother had planned music, she had planned the ministry, she had planned even medicine; but being so interested in football, well, it was sort of a hindrance to me, because I concentrated there instead of academics. It was the same way all the way through college. This was the beginning of a great life--this transfer to East Carolina. My mother was very much against it. She said, “That's a girl school. You're just going there because of the football.” In fact, I was on my way when I called to tell her.

H.A.I. Sugg:

I know it was a girls' school, because Mary Lou and practically all of her six elder sisters went there.

William M. A. Greene:

Ginny's mother went to the East Carolina Teachers Training School, and then came back and graduated through East Carolina Teachers College.

I was happy, and when I got there I had such support from the school. In those days, we paid thirty-five dollars a quarter. That included our meals in the school dining hall.

There were no boys' dormitories, so we located in town. I was one of the fortunate ones in that the football coach arranged for my living quarters. The fellow that played football with me and had been my roommate in Brevard and I went to live with Mrs. E. B. Ficklen, a widow in west Greenville, in a beautiful big mansion, off of Fifth Street. It's now a fraternity house. She was so good to us. Our requirement was that one of us was to be there by ten o'clock at night, because she didn't want to be alone. That's why we were in the home, plus the fact the coach was such a personality he was able to win people's hearts to help him with his football players. I enjoyed living at her house. It was quiet, and of all things, we had a butler, four-poster beds and a bedroom, our own bath, and that type of thing. You couldn't ask for better. Here are two guys who had maybe two shirts and one suit in this beautiful, big home.

Along came the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. At this time I was in my junior year. Shortly thereafter, in January of 1942, I went to the recruiting office in Raleigh. I read about the V-7 U.S. Naval Reserve program: You had a to be a junior or a senior in college, and you had to seek an appointment and complete the college work prior to being called into active duty. Well, that I did, and upon graduation in 1943, I was ordered to Northwestern University for what we call the V-7, Victor 7. In December [1943], I graduated as an ensign, U.S. Naval Reserve, and was ordered off to Little Creek, Virginia, to the Amphibious Training Base for assault craft.

I stayed there from 31 December until March 1944. Some of our people were ordered to ships or other duty leading to the Normandy Invasion. But a number of us were transferred on to Fort Pierce, Florida, for further assault training and to train boat crews.

Meanwhile, the highlight of my life there was the fact that Ginny, my wife, and I were married on 26 February, 1944. This is before we transferred to Florida.

H.A.I. Sugg:

That reminds me, Charlie Bissette has a story that he tells about you courting Ginny on his front steps and about going on your honeymoon with Ginny.

William M. A. Greene:

Oh, that's a good story. We took him back to Greenville, to East Carolina, because we only had a short weekend honeymoon. I was literally “helped” to get off the base. We were in what we call a “freezing mode,” because we were being sent to ships overseas or to new ships in the United States, to Maryland, where there was other amphibious training.

We were married at high noon on Saturday, 26 February. I was in a situation of not having official permission to be off the Little Creek base, but I was over at the Naval base next door. We had to arrange with the chaplain to take care of our wedding. It was interesting. He said, “I don't charge anything, but you can slip the organist a couple of dollars”--that being a Navy musician. We had a very lovely wedding and a short honeymoon out at nearby Virginia Beach.

Charlie Bissette, my friend from Greenville, was a junior lieutenant in the supply corps at the amphibious base in Little Creek. It so happened he was going back to Greenville on Monday to visit, and he gave her [my wife] a ride back to East Carolina Teacher's College, where she was in her sophomore year.

She joined me in Fort Pierce after the end of the academic year, which was about the end of May. I stayed there training more boat crews. Instead of being assigned to a ship, I kept getting little promotions. By the time I left in January 1945, I had my own group to take to sea with me, officers and men. And so off we went to the USS HANOVER up in Newport, Rhode Island, for pre-commissioning detail--training and getting ready to

join the ship, then under construction at Pascagoula, Mississippi. Ginny came down, and we lived in a little rented place there in Pascagoula. We got along fine, despite the fact that we had bad dogs on the street. The difficulty was finding places suitable for meals. Pascagoula is a different place today by the way.

Our ship, the USS HANOVER, named for a county in Virginia, was an auxiliary assault transport ship, troop transport. In April of that year, 1945, off we went to shakedown in Galveston, Texas, after the commissioning. From there, we were off to the Pacific Fleet. Ginny and one of my fellow officer's wife from Canada went back to live in Norfolk for a while. We were hoping that we might stop in at Norfolk before we deployed, but we didn't. We got through our shakedown at Galveston, Texas. That was it . . . then off to Hawaii with a load of Seabees from the gulf area and a cargo compartment full of beer. This we offloaded in Hawaii, and it was distributed somewhere through the Pacific Fleet.

H.A.I. Sugg:

I can remember some of those distributions. They were great lifesavers out there.

William M. A. Greene:

We managed to slip a few cases of beer around the side for our own use later on, and at some places we were able to play softball when the occasion allowed us.

We went back to Portland, Oregon, and got loaded up with an army unit for the Okinawa invasion. It was already under way, but we got in there and made our landing with our people. That was quite an experience; we “thought” we were prepared. I was the whole Group Commander, but I had additional duty as battery officer for a forty-millimeter, twin mount at the time of the landing. We put all thirty-two boats into the water, and I would go over the side and lead the boats to wherever we were assigned a landing, with our troops embarked and the Jeeps and other light rolling stock we called it.

The war ended in August of that year, but we were getting to Manila at the time, and our ship was preparing for an invasion of Japan, southern Japan. We didn't know exactly for what we were preparing, but all we knew was we were getting ready for an invasion. So it was a happy day when the war ended. We started at that point on a mission of taking Chinese troops from Kowloon, Hong Kong, up to Tsingtao, in the first cruise; and the second cruise we went to Chen Huang Tao. The second voyage we were taking Chinese troops to repel the Communist troops' last move down from Manchuria.

Now, interestingly enough, we went through two class five typhoons in the USS HANOVER. I guess that is one of the times in my life that I have been so scared, when we were rolling sixty degrees in this big ship, wondering if we're just going to keep going over. That was off the coast of Formosa, which is Taiwan. The Chinese became sick, with everyone else being sick. We were just hoping we would not lose any of them over the side. We didn't want to lose anybody. But we survived that.

The only death that did occur on that particular voyage was when a young Chinese lieutenant shot one of his men, because he wouldn't eat his rice. You see, we were preparing rice down below, and we would bring it up on deck and serve the rice to them. Well, this fellow was seasick and didn't want to eat anything, but the guy just pulled out his gun “bam.” I was officer of the deck, looking down from the bridge. The captain of the ship was Joe Calahan, an outstanding person. He was another one of those submariners with whom I served. He came and got the commanding general of the group out, and he said, “Now look, General. I am the captain of the ship, and we don't allow shooting aboard!” So we buried the man at sea. Had a very nice ceremony. Some of the people sang the Chinese National Anthem. Well, enough of that.

The other mission we got into was what was called the Magic Carpet. We were bringing all services back from Japan and nearby areas to the United States for dismissal or separation from the military, the war having ended. It just got to be interesting. I think we made two: one to Seattle and the other to San Francisco.

In mid February of 1946, I was detached from the USS HANOVER for separation from active duty. I had been considering applying for a permanent appointment in the Navy; I wanted very much to be a Naval officer. But, I wanted to wait until I got home to talk it over with Ginny, although we had been writing back and forth. The captain was encouraging me for some reason; although he was on my back all the time, particularly as officer of the deck. It was good for me; it helped in later years. I wanted to wait and talk with her personally, so we did.

We got back just in time for our second wedding anniversary. I arrived back in Washington by air from San Francisco. She and her stepfather, Snyder, a fine gentleman, both met me. We came on back down to Virginia to Little Creek, where I received my official separation. I immediately applied for a permanent commission, after having discussed it with Ginny. I was ordered to active duty, but not until January of 1947. I was sent to Charleston, South Carolina, where I joined the USS BURDO (APD133), still an amphibious-force type. I was trying to get destroyer duty, you see.

H.A.I. Sugg:

What was the name of the ship?

William M. A. Greene:

BURDO, named for a corporal in the Marine Corps who was killed in active duty in World War II.

I served on the BURDO on some very interesting assignments, including Atlantic training cruises, where you land the UDTs. We had four amphibious assault craft, normally used by the UDT for their underwater work. UDT, that's underwater demolition team.

Now again I very much wanted a destroyer assignment. I had a skipper named Messer who happened to know the detailer in the Bureau of Naval Personnel who had been his skipper on a previous ship when he was his executive officer. I had received orders from BURDO to a small cargo ship to transport groceries and household needs for ships from Greenland over to Iceland, up in those waters. I called it a “spit kit.” Anyhow, Captain Messer, then a lieutenant commander and skipper of our ship, called his detailer in Washington, and they sure enough ordered me to the USS JAMES C. OWENS (DD776). That was in June of 1948.

I might comment here about another important event in our lives. Our first child, Virginia Ruth, was born in March 1948 in the Naval hospital in Portsmouth, Virginia. So, off I went to the Mediterranean to find the USS JAMES C. OWENS. Ginny and our little baby stayed behind with her parents and then went back to Norfolk, our homeport, later in the year. In January 1950, our ship was ordered to Charleston for decommissioning. At that time I received orders to go on to report to the General Line School at Monterey, California.

H.A.I. Sugg:

What was your rank then?

William M. A. Greene:

I was still a junior lieutenant; I had been since April 1945. We were in that group called the “hump,” which they extended us for five years, I think. Anyhow I had been at that point, selected for lieutenant . . . this had occurred in 1949, but I would not be promoted until July 1950.

The General Line School, I might add here, was designed as a ten-month intensive study for those officers who had entered the permanent commission, without going to the US Naval Academy or Naval ROTC. I had been through what is called the Naval Reserve Midshipman School, but some of the people (there were five hundred of us there) were entering from other sources. I was given that opportunity, and so it was a good year. Ten months of professional subjects: engineering, gunnery, seamanship, navigation, and we even had foreign affairs.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Monterey was a pretty nice place to live.

William M. A. Greene:

Monterey was a wonderful place to live. We had the Old El Montey Hotel. Ginny and I enjoyed some golf there, and the social life with our people. It is interesting that of that class of five hundred, I think less than two hundred were surface, the rest of them were aviators. So I learned a lot about Naval aviation. As a matter a fact, my best grade was in aviation, a lot better than those subjects that I should have been more acquainted with. I had a skipper, instructor, named Leonard. He offered to anybody in the class a big old “A” if they would write a history of Naval Aviation in lieu of taking the final examination. Well, I jumped on that, because I don't take exams well anyhow. I enjoyed doing the research and finding out all about the fact that Eli Whitney was the first pilot of the United States Navy, and he flew off the old PENNSYLVANIA--they put a little flight deck on the battleship.

After line school, graduating from there in December of 1950, I was given an assignment as aide and flag lieutenant to Commander Amphibious Group 4 back in Little Creek, Virginia.

H.A.I. Sugg:

By the way I was in the Phib Group 4 staff later.

William M. A. Greene:

Really?

H.A.I. Sugg:

Yes.

William M. A. Greene:

Well, I had Rear Admiral Harold George Hazard, another fine gentleman out of the Class of 1922 at the Naval Academy.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Oh yes, I knew him.

William M. A. Greene:

He taught me so much, particularly in protocol. He would correct me so many times when I would make mistakes. Like the junior leaves the ship ahead of the senior, and I always insisted that the boss go ahead of me. I'd been taught that manners were opening doors for my seniors. He was great; he and his wife, Betty, were so good to my family and me. We kept in touch for many years, and then he was ordered to Germany as commander of Navy German forces. I was hoping to go along with him, but the Bureau of Naval Personnel said that was not good, professionally.

I went to the Naval Academy for two years as an instructor at that time, and I was a lieutenant. I even got to choose the course I wanted to be an instructor in. The reason I got that opportunity is because I asked for it.

Not having gone to the Naval Academy, I wrote and asked for a copy of Reef Points, which is known as the plebes bible. The reason I asked for Reef Points was because Admiral Laurens' son Skip, a 1950 graduate, and I became great friends, and in fact I was the chief usher at his wedding. He told me that was the book I needed to read. Well, I got a copy of Reef Points sent to me by Captain R. T. S. Keith, who was later my boss at sea. And I read that book . . . and I read it . . . and when I got to the Naval Academy in June of 1952, I knew all the monuments; I knew the history of Thompson Stadium; and I knew the history of the Dewey Basin, the old marina for the REINA MERCEDES, which was parked there as a barracks for the stewardsmen who handled the mess hall serving. I knew all about

Mahan Hall. The Chapel in particular was of interest to me . . . the fact that the windows on one side of the Chapel were the Old Testament and on the other side were the New Testament, all given by various classes. The John Paul Jones crypt was in the basement level of the Chapel, having not been brought back to France yet.

H.A.I. Sugg:

That reminds me of the old song we used to sing, “Everybody works but John Paul and he's preserved in alcohol”. . . excuse me.

[Laughter]!William M. A. Greene:

The most fun I had in those two years was watching the plebes climb the Herndon Monument. It was out in front of the Naval Academy Chapel. They had to climb up the monument and put a little hat on top of it before they could declare themselves “no more plebes.” I went out there and just laughed watching them, because the first classmen come out the night before and grease it.

I asked if I might help with the football program. As you might imagine I wanted to get involved somehow. I was asked to serve as an end coach for the 150-pound football team, which is one of the finest programs they had. We had the Naval Academy and the Ivy League Schools, and eventually the Military Academy got into that, too. I coached that for two years. We went undefeated. The second year I was the head coach.

All right, now, I could dwell on the Naval Academy from now on but I, of course, came back again to the Naval Academy.

H.A.I. Sugg:

What department were you in?

William M. A. Greene:

Ordnance and Gunnery. I was teaching second-class ordnance and gunnery. You know it had been my toughest course in the General Line School. I had almost flunked it, learning a lot of . . . memorizing a lot of symbols, peculiar to ordnance and gunnery. In

today's computerized Navy we might do about the bearing angle, the training angle and the range, and all these things; but we used to have to crank in and work it out by hand, exactly how it was . . . allowing for the wind and those things. But they have it computerized now.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Back . . . were you still in the days of the eight-place logarithm tables?

William M. A. Greene:

Oh yeah. That again was an experience that I'm so happy my family and I enjoyed. Our second child, Caroline, was born just about a couple of weeks before we went to the Naval Academy in 1952. It worked out fine to have two years of being home with my daughter. She was a joy and has been a joy and is a joy! We left the Naval Academy in 1954. I was ordered to Hawaii as executive officer on a destroyer, the USSNICHOLAS.

H.A.I. Sugg:

We helped escort the USS WASHINGTON to the Pacific--the NICHOLAS, the BARTON, and the MEADE.

William M. A. Greene:

Unfortunately, I had only been aboard for three months when our little daughter Ginny Ruth, then six years of age, became ill, and we learned it was a brain tumor, inoperable. The Navy was good enough, generous and gracious enough, compassionate enough to fly the whole family back to Washington. The Air Force helped along the way from Travis Air Force Base in California to Andrews in Washington, in a special plane, just my family. You see this type of thing . . . I used to tell people when I was trying to get them interested in going into the naval service . . . you don't get that in most places. The whole Navy came to our side. People I had never heard of got our house packed up and shipped back to Washington. She was ill about nine months at the Naval hospital in Bethesda. We went there because they were a bit more advanced in radiology treatments. Of course, it didn't do anything except postpone the inevitable. She died in August of 1955. Hadn't been ill but nine months. I had humanitarian duty in Washington during this time. Once again

the Navy was gracious to me. My mind wasn't there. I was just going into the office and helping the Bureau of Personnel. I was ordered back to sea again after her death. I reported to the USS MITSCHER, named for Admiral Mitscher of World War II fame, as executive officer. I had been executive officer previously on the NICHOLAS.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Your rank by now?

William M. A. Greene:

Lieutenant commander by now. I had been selected for lieutenant commander while in Washington on the humanitarian duty in 1954. I stayed on the MITSCHER from 1956 until 1957. I want to add that we had just an outstanding commanding officer named Sheldon H. Kinney, Superintendent of the Naval Academy later on.

Mitscher was a very famous naval aviator in World War II and was in command of the USS HORNET at the battle of Midway. Again, I learned so much under Commander Kinney, not only ship handling, but also in procedures and protocol. Interestingly enough I wanted to have a bugle. This huge destroyer leader named MITSCHER was as large as some of the cruisers had been in World War II. But we did everything by the bugle. We weren't very popular in some places because we would go into a Naval Station and if we didn't hear the bugle, we'd sound reveille at six o'clock in the morning. That didn't go too well with some of the local residents of quarters at Norfolk or Key West or some of the other places. But we had a very fine ship; the morale was high because of Sheldon Kinney. I learned how to be a commanding officer under him. He was such a fine person to the people, that somebody had to be the old devil and that was me, the executive officer.

H.A.I. Sugg:

That is usually the arrangement.

William M. A. Greene:

It wasn't my nature, but I wound up successful with it anyhow. I went on to command my own ship from there, a destroyer escort named TABBERER, named for a

gentleman from Georgia who was killed in World War II. I stayed with that ship from August of 1957 until July of 1958. Then I was ordered to Naval War College, Command and Staff Course, for a year. I was very pleased when I received a notice to report to the office of the president of the Naval War College. I said, “Oh, Lord, they don't like my term paper. Something's wrong.” In the Naval War College, we had to write and do research and do papers as well as listen to fine lectures and do studies and do war games. He said, “The Superintendent of the Naval Academy wants to interview you for the position of Secretary of Treasurer and Editor at the Naval Institute.”

“Me, Sir?”

H.A.I. Sugg:

Who was the president of the Naval War College?

William M. A. Greene:

Ingersoll. Vice Admiral Ingersoll. He said, “I'm going to Washington, flying down there for official reasons in a couple of days. You can ride with me.” So I flew to Washington with Admiral Ingersoll and had a chance to talk with him a while. He was a great president of the Naval War College. When he introduced himself at the beginning and spoke to the whole senior and junior class at the Naval War College, he made it clear that nobody was wrong and nobody was right. You came here to mix your opinions and have a chance to express yourself and to learn how we take care of keeping the United States at peace for as long as we can with our diplomacy, and if that doesn't work, how to go beat somebody up with our Armed Forces, mostly the Navy.

I went over to the Naval Academy and it turned out my good friend and previous skipper, Sheldon Kinney, then a captain, who was on the Board of Control at the Naval Institute, had recommended me to the Board to succeed a fellow named Commander Robert Adrian, who had been there three years. So I arrived in Washington and I went over to see

Captain Kinney because I had been notified by him that I should come to his office when I arrived in Washington. He knew I was coming. So I stayed the night with him and the next morning his wife took me over to the superintendent's office of the Naval Academy and I had an interview. He said, “Look around and see how you feel.” I didn't have to look around, but I did; I knew I wanted that job.

Returning to the Naval War College and hoping I was going to have the assignment, I reported back to my wife Ginny that this is what took place. I was ordered to the Naval Academy as Aide and Special Assistant to the Superintendent of the United States Naval Academy, then Rear Admiral Charles Nelson, who had been chief of staff there when I was an instructor back in 1952-54. So this was, of course, 1959. We arrived in July. While at the Naval War College our son Bill, number three child, came along . . . born at the Naval Hospital in Newport. That was in September of 1958. So from the arrival time till the departure in 1962, I had just a wonderful three years as Special Assistant and Aide.

Special Assistant was a person who was in charge of all the visitors to the Naval Academy--and there were hundreds of thousands. I specifically identified . . . to be sure of any Congressional friends who came. I enjoyed that very much, showing off the Naval Academy. I enjoyed particularly taking people to Bancroft Hall for the, what they call the Noon Meal Formation for Midshipmen, and into the Chapel. I would get carried away and become emotional in the Chapel. That was one of those problems with my showing people, because I was so touched by all the history of that Chapel along with all the history of the Naval Academy, but particularly the Chapel.

Rear Admiral John F. Davidson must be one of the finest people I've met in my lifetime. I must give an example of his philosophy as a person and as a flag officer. On one

occasion we received a telephone call--I did as his aide--from somebody in the southwestern states, telling me that Midshipman “Joe Blow,” or whatever his name might be, was married. Now bear in mind that midshipmen could not be married. They could not marry until ten seconds after they graduated and were commissioned. I asked for the man's name and he said, “I don't want to give you my name.” Two or three more questions, and I got nothing further. So I just mentioned to the Admiral and he said, “Pay no attention to it.” Then two days later along came a letter reporting that midshipman so and so was married. And I thought he should know about it, so I showed the letter to the Admiral . . . it had the postmark of where it came from . . . and he said, “Put that in a safe and don't do anymore investigating of where it came from.” That was the end of it, we heard no more.

I had such respect for him from that, but I already had respect for him before that. He and his wife were just the finest hosts. He had receptions and he had official functions daily. They both are dead now, both buried at the Naval Academy Cemetery overlooking the great Severn River. They have one of the nicest plots up there on that beautiful hill.

I left the Naval Academy in June of 1962 to go to Camden, New Jersey, where a ship named the USS JOSEPH STRAUSS, missile destroyer (#16), was under construction. I was the prospective commanding officer. I was so pleased with the orders. I said, “This is going to be my own ship to put into commission.” Seven months later she was completed and my whole ship's company had been assembled. A lot of them were new people, new recruits, that had gone through boot training. One of the young officers and I designed the coat of arms. It's got the red and black--Admiral Strauss was in ordnance--and the Navy blue and gold, of course, which is for the Naval Academy colors. Promptus adAgendum,

“Ready for Action,” was the motto I wanted to use. I had to go to the Catholic chaplain at the Naval Academy, whom I knew, and ask him to get me the Latin translation.

We commissioned the JOSEPH STRAUSS in April 20, 1963, and off we went into the Atlantic Ocean and operated. We went on to Norfolk for our acceptance inspection, then on back to Long Beach, California, for the homeport. We stopped off at several nice liberty ports, which we had arranged, one of them being Acapulco, Mexico. That was the highlight of the voyage. I stayed with the JOSEPH STRAUSS until July 1964. I was relieved by a fellow named Bruce Keener (now a retired rear admiral) at Yokosuka, Japan. I was then ordered back to Washington to the Ships Material Readiness Division, heading a desk, which was called the Battleship, Cruiser, Destroyer Desk, to assist the Bureau of Ships and the various type commanders with their maintenance needs and material needs. Well, I remained there until two years later, June 1966.

In June 1966, I went to the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, which is in Fort McNair, Washington. A very fine year of study: “A let's win through diplomacy if we can, otherwise we go to war and win attitude.” The Industrial College of the Armed Forces was designed to teach us how to deal with industry, which is something that our armed forces needed. We had some lousy contracts, as you know, from not having persons qualified to deal with those fast talkers in industry who charge too much. So the year in the Industrial College was again very rewarding to me, and I was able to complete my Masters degree in International Affairs in nearby George Washington University, in night classes.

H.A.I. Sugg:

That was 1967?

William M. A. Greene:

Yes.

H.A.I. Sugg:

That was the year I came to ECU.

William M. A. Greene:

Yes, I remember.

Well, from the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, I went to Hawaii again for my third command, the USS PONCHATOULA's fleet order. The mission of the PONCHATOULA was to take fuel oil for the boilers of ships, JP5 fuel for the jet aircraft, and aviation gasoline for the propeller-driven aircraft, out to the Pacific fleets in Vietnam. We transported the fuel to ships that were underway to the Gulf of Tonkin . . . sixty to one hundred feet apart with hoses rigged between the ships. We also delivered freight and sometimes we transferred people. We operated out of Subic Bay in the Philippines and on out to the Gulf of Tonkin. I stayed with that assignment--wonderful ship, great crew--until 1968, I guess, November of 1968.

I was relieved in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and ordered to the USS WILLIAM H. STANDLEY, a guided missile cruiser, as commanding officer. I relieved a gentleman at Pearl Harbor while the ship was in route to the Western Pacific for the Vietnam War. Same location, as PONCHATOULA's homeport. On the twenty-fourth of December 1968 I took command of the WILLIAM H. STANDLEY. I made a short speech. We had a number of people onboard for the change-of-command ceremony. I stood up and said, “Twas the day before Christmas and from all through the land the nice people gathered for a change in command.” The ship's company was gathered out on the flight deck, where we held the ceremony, and I said, “You people have a good liberty here in Hawaii. Have a happy Christmas. I will be with my family, and I wish you could be with yours. We are going to be gone a long time so have fun and behave.” Something like that.

We got underway on the twenty-sixth. We departed Pearl Harbor for the Gulf of Tonkin and the Vietnam War. We were out there until June of 1969. We returned to the

United States and on to Mayport, which was our homeport of course. That was a very successful cruise and our ship did well. The people worked hard to get her ready for the war. And she did perform remarkably well. I was well acquainted with the Tonkin Gulf, having been all over it in the fleet oiler.

In May 1970, I was relieved of command of the WILLIAM H. STANDLEY and ordered to the Bureau of Navy Personnel to head up Navy recruiting. I had been selected at that time for rear admiral flag rank and there I stayed until we departed in April of 1972.

In 1971, the draft having been ended, I was directed to establish a Navy Recruiting Command, which would no longer be a division of the Bureau of Personnel. I went into town into a business office building and set up offices as a major recruiting operation. That was the biggest challenge I had in my whole Naval career. I was trying to get the recruiting under the conditions of which we would have people volunteer. There was much against it. People, as you recall, the citizens of the United States, did not like the Vietnam War, particularly the young people. Nobody in my presence ever said to me, “We shouldn't be here.”

But even people who had been drafted. . . . One of the finest officers I had aboard the PONCHATOULA was a rascal. On his liberty time he had a little A-frame building and he would get his motorcycle and ride and just tear up the place. But not in his Navy uniform and not with anybody who was part of the Naval service. When it came time for him to be in his uniform and onboard ship he was one of the sharpest officers I've ever seen. He had the best personnel inspections. I would go to inspect his division and they were the sharpest looking in the ship. A young junior lieutenant and you would never think he would be a rascal.

As a matter of fact I went to bat for him one time. He had been accused of having marijuana. He told me he did not have it but had been in town with a group of people with whom he hadn't associated with--that was one of his times in civilian clothing--and he said he did not do it. I said, “I believe you.” Well, back to recruiting.

We had a man killed, a first class petty officer, in New York City. He was stabbed on the corner. He was just standing in his blue uniform. And we had a young officer harassed for eight hours in a car on campus at a major university. The students took turns rocking the car from one side to the other and would not let him out to go to the bathroom or get food. For eight hours, he stayed there. That is very inhumane, I mean, that is just unacceptable. I went to see J. Edgar Hoover, FBI, because I was not getting far with the police forces and some of the other law enforcement folks. I said, “I need help.” It is interesting how I got in to see him.

A gentleman named Ed Mason, who would have graduated from the Naval Academy in the late 1930s . . . I don't think it was 1939, I think he was a little ahead of 1939 . . . but for some reason he acquired some stomach difficulties and had to leave the Academy. He never did graduate, but he went into the FBI for twenty years and became great friends with J. Edgar Hoover. I was telling him about my problems and he said, “Let's go on over and see the boss.” We called them “Boys in Columbus.” Tthe next thing I knew the FBI office had called me and said, “You have an appointment with Mr. Hoover at ten o'clock.” So my aide and I went there. What I didn't realize was that I was sitting on a trap door the entire time I was talking to the FBI director. My young aide, who was allowed to come in, said, “I noticed that where you were sitting, the floor was cut all the way around. Why, you could have been dumped!” Over on the window behind the Director sat a

gentleman in a tan suit looking at me, right at my eyes the whole time I was there, for ten or fifteen minutes. He was cocked sideways. He had a piece of hardware on that other side that he could have pulled out pretty fast, if I so much as made a move. I'm just rambling now, but that was the greatest challenge of my lifetime or in the history of my Naval career.

H.A.I. Sugg:

You certainly got that job at a bad time.

William M. A. Greene:

It's interesting. The Army knew we needed publicity. We needed a lot of commercials. But the Air Force and the Navy went, “Oh, we don't need that, we'll go out in our uniforms and attract people. We love our service so much.” The brigadier general was always trying to upstage us somehow. I called him the “Tricky Briggidy” because he was always trying to get the same men I wanted.

It's unfortunate that we didn't realize the fact that the draft was helping us so much. Now, Admiral Zumwalt, with whom I disagree with so much on many of his programs. . . .

H.A.I. Sugg:

Former student of mine.

William M. A. Greene:

Was probably a good student, but he was not a good skipper of ships. He sent a message to the Chief of Naval Personnel, which was sent on to me, and it read like this, “I need to know how we are going to approach recruiting, to be successful, assuming the draft ends. I need innovative, imaginative, and even heroic means of getting the job done.” That's exactly how it read. I remember I broadcast it all through my 837 people, I think I had. Well, the message came on to me for action of course. We came up with all sorts of ideas. We would use the Blue Angels, the Navy Band, the steel bands from down in the Caribbean. That was not what was needed. We didn't know right then exactly what was needed. We knew if they would listen we could attract people there because we could offer them, not necessarily the Naval Academy, if they qualified, but the ROTC. For the

chaplains and medical personnel we could offer specialized programs. But it was a difficult time and we still are having trouble at this point in making our numbers in recruiting for the Navy.

Right after the recruiting command, I went to the command of a Destroyer Flotilla, a Cruise Destroyer Flotilla, Flotilla Number 4 in Norfolk, in April of 1972. I was there only a short time when that flotilla was placed out of commission and I moved out to the Inshore Warfare Command in December 1972 or January of 1973. Along came the summertime and I made a big mistake.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Excuse me, what was the inshore, what was that?

William M. A. Greene:

The Naval Inshore Warfare Command. I went there in January of 1973. It is a special warfare group that is composed of the Seals, the Underwater Demolition Team, the Assault Craft training . . . like where I was from the beginning with the landing craft. It had an intelligence group, and it had an explosive ordnance disposal group, and it was quite an interesting experience for me. There were some real dedicated people in there like the other Navy branches.

Along in the summer, I was approached by a gentleman from North Carolina wanting me to come down and take over the position as the executive vice president of a resort development named Brandywine Bay outside of Morehead City. Well, it had a good salary attached and also ten percent of the profits before taxes. Well, the most naive sailor that ever walked listened to this person. I will not give his name, because he's been one of our state's leading officials in recent years, but he was a salesman, I tell you, and I was a listener. I thought at this time it would be good to get our son, Bill, in one place to go through high school. He had been bounced around from school to school without the

opportunity of continuity. I told the Chief of Naval Personnel and talked it over with him, and the result was I retired in November 1973.

I took the position and stayed with it less than three months. I resigned for two reasons: I didn't like the crookedness I was experiencing, and I didn't like the fact that the lender of the $9 million they were putting into the program was cutting off the money, because the so-called president, who had employed me, had said he would put $300,000 into it and he hadn't put one cent in. Fortunately, I was appointed to the State Ports Authority as executive director. I served there for eight years until I reached sixty-five and it was time to retire, according to the State of North Carolina, so I did.

H.A.I. Sugg:

This makes a good stopping point I think, to take up a little later your experiences in the State Ports Authority and so on.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Break in Interview

William M. A. Greene:

All right . . . aboard the USS MONROVI.

H.A.I. Sugg:

This is in Liberia?

William M. A. Greene:

Yes, this is Liberia. I had side boys and honors arranged for him as a brigadier general, of course. Well, he stumbled through that and inspected the honor guard. He was standing up so straight . . . the men were standing at “present arms” and he decided he was going to take one of those rifles and look at it. It was a Marine honor guard. We had Marines on board on the way to the Mediterranean. So this Marine decided he wasn't going to give up his rifle. He stood there at “present arms” and the general grabbed the rifle and started pulling on it and the Marine came up with it. He sort of turned the rifle loose and

looked at him. I arranged somehow with the young lieutenant in charge of the honor guard to put the men at “order arms,” which he did. Then the Marine held his rifle up so he could look at. He cocked it and looked down the barrel. It was embarrassing, and it made some of the members of the crew standing out there laugh. I could hear them. I got clear and I took him up and gave him a cup of coffee somewhere. The admiral was also arranging a dinner on board the MONROVIA.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Which admiral was this?

William M. A. Greene:

Admiral Orem, Howard Orem. We got through that all right.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Glad he got to inspect the rifle.

William M. A. Greene:

He got to inspect the rifle.

H.A.I. Sugg:

They teach the Marines, “Never release your weapon.”

William M. A. Greene:

Boy, standing there with his rifle, the general grabbed it; he was not really a military man, you could tell that. He'd been trying to be so military, and he was not really a military man, just someone put in a brigadiers general uniform. You should have seen them return our salute, and we fired a twenty-one-gun salute as we were going in to port. I could see them firing those little three-pounders from over the battery. Later on we went off to the Hills Mine to inspect it. A West Point graduate returned and was president of that. We went with the president, President Tubman, to visit his mines. So in this gun salute, I saw the same old little bitty three-pounders bouncing on the ground.

H.A.I. Sugg:

I assume you had blank charges for your salute?

William M. A. Greene:

Blank charges for that five-inch gun. We had arranged to get those before we ever left Norfolk. Of course, they did not have a saluting battery on that ship.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Well, you do the best you can. Okay, let me change the tape here.

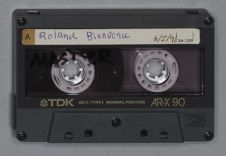

[TAPE 2. SIDE A.]

H.A.I. Sugg:

You were talking about going to the North Carolina State Ports Authority. . . . Give me a little more information on the Ports Authority and what you did while you were there.

William M. A. Greene:

My interest in the North Carolina Ports Authority commenced during my active Naval Service. I noticed a lot of cargo going through Norfolk, Virginia, and Charleston, South Carolina, but not with any North Carolina identification on it. I wondered . . . if we have ports in North Carolina, why not ship through our own ports. When I had erroneously and naively left the Navy, and that other business didn't work out, I applied for the position as executive director of the State Ports Authority, that position having been vacated. I didn't get too much response until 1977. Finally, the Secretary of Commerce, who was responsible for personnel in the Ports Authority by the general statutes, recommended me to Governor Hunt as the executive director. I had gone to visit the Secretary of Commerce.

H.A.I. Sugg:

What year was this?

William M. A. Greene:

1977. I was called to be interviewed by the Governor and he asked me why I thought . . . why I was interested in the State Ports Authority. I had a good professional background already and did, I really did, want to work. I said, “I want to make North Carolina competitive. As a matter of fact, my competitive spirit will be insulted if we can't use our own ports for cargo in North Carolina.” So I was appointed in September, 1977, and I set out then to bring Morehead City up and away from the bad side of the ledger. It had been losing money for years. They hadn't developed Morehead City or Wilmington. Wilmington is an old, ship-building yard from World War II. In fact I think it dated back to World War I, building merchant ships. I worked hard and learned right away I needed to visit foreign countries and needed to become a member of the American Association of

Ports Authorities, which is headquartered in Alexandria, Virginia, or was in Washington then. The ports throughout the United States are very competitive, but we do not have the largest ports. The largest ports are in Germany and Singapore. We have growing ports. I felt that if we could develop our five ports commensurate with their potential that we could move ahead of the game. Well, we did. Fortunately, we had a very good Board of Directors. Amongst them was their Chairman, Thomas Taft, of Greenville, an attorney. The main strength on the Board, however, was a gentleman named Collin Stokes.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Was that Thomas Taft?

William M. A. Greene:

Thomas Taft. Hoover Taft's son. Chairman, because he was close to Governor Hunt. Mine was not a political appointment, and I made it clear I was interested in the appointment there because of my professional background and my interest in developing ports.

Anyhow, Collin Stokes, who was the Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer of the Reynolds Tobacco Company at that time, was really a mainspring on the Board because of his experience and his interest. He was very interested, highly interested in North Carolina's growth. We had other members, I'll not go into all their names, but they had been appointed by the Governor and by the General Assembly: seven by the Governor and four by the General Assembly, two from the Speaker of the House and two from the President of the Senate, who would be Lieutenant Governor, of course. We met every other month and we met sometimes in Morehead, sometimes in Wilmington, sometimes in Raleigh, sometime Greensboro, or even on one occasion in High Point. We were trying to get business with various areas.

My greatest experiences came in visiting the foreign countries and trying to make them understand that North Carolina is a maritime state. They had heard very little about North Carolina . . . a lot about Norfolk and Charleston, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia. Let me say now, and this is very germane to our conversation, that through the years in this century Norfolk has been known as an international port, of course, because of the deep waters there and the fact that they have good railroads coming in and highways. Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina, came along in the middle part of the century and really developed in a hurry. Why? Because the governors of the states got behind them and recognized that the maritime traffic was awfully important to the economy. North Carolina did not. This state has been thinking of highways, highways, and highways for all these years! Not too much on airports, and not too much on seaports.

H.A.I. Sugg:

The contractors and the bureaucrats make more money on the highways.

William M. A. Greene:

The paving contractors in particular, I guess, made more money there, and the lobbying there is stronger. Very little lobbying for seaports, very little lobbying for airports; so it was an uphill fight. Fortunately, with the good Board and our hard work, we did make Morehead City realize a growth, principally because I kept emphasizing it as a bulk port. Because of the deep water, the large bulk ships could come in and out of Morehead City. It is not a general cargo or container-type port, although somebody, politically, had tried to make it a container port by putting a big container crane there. We had to move it to Wilmington, because we were paying a hundred thousand dollars a year for the maintenance and the debt service on that crane, and it was not being used. So I asked the Board to move it to Wilmington and they did. That gave two cranes in Wilmington and that improved our situation. Now we have about six cranes there . . . but. . . .

H.A.I. Sugg:

Outrage in Morehead!

William M. A. Greene:

That's right. Outrage in Morehead! I thought they were going to burn my house. You know I kept emphasizing bulk cargo. I wanted to put a grain elevator at Radio Island because we have a lot of grain going out of North Carolina. Over in Greenville ____ _____?______, a lot of grain is going through the elevators out there--north Greenville.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Fred Webb's.

William M. A. Greene:

Yes. Fred Webb's business. I even asked his counsel.

Well, the opportunity came for coal, because the petroleum prices went sky high you recall in the late 1970s. We got a coal company to come to Morehead City through my making announcements and speeches that we wanted to bring coal to Morehead City. We had a deep port there and we had a place to load it and we could set up a conveyor system, which we did. We got a contract with a company that was for a million dollars for a year. I said, “This is the lowest amount we will accept to get a contract to bring coal here.” I knew the million dollars a year would pay for a lot of what we were losing, because of empty warehouse space and empty docks, and the port not being used for what it is best fitted. I said, “This will put us in the black.” There was a lot of resistance there about bringing coal into Morehead City, afraid of the dust. The New Bern people, particularly, didn't like the fact that coal trains were going through.

A Morehead City attorney came to a meeting with the Council of State in Raleigh about having coal coming through Morehead City. The attorney for Morehead City said that the heavy trains going through Morehead City “would rattle the cups and the saucers and break the plates, and cause the dishes to fall off the shelves.” Oh, he was very dramatic.

So I responded. I said, “Well, you know, we've been bringing petroleum through Morehead City from Radio Island.” The tankers would come in with JP5 fuel for the jet aircraft at Cherry Point and Hillsboro Air Force Base. I said, “Petroleum is heavier than coal.” Sure enough it turned out I was right, sort of defeated the argument that we were going to rattle the dishes. The dust, we assured people, we could control, and it was agreed that we could bring coal into Morehead City. The conveyor system there now is used for wood chips shipped out by Weyerhauser Company, and that is a great benefit for our economy of the port and the State. The coal didn't last too long because the fuel prices dropped again and many people who were gearing up to use coal decided they would not and stuck with their petroleum for heating and for power plants.

In Wilmington I saw progressive growth, progressive opportunity there through business to foreign countries and becoming a member of the International Association of Ports and Harbors. We wanted to be able to dredge the Cape Fear River to about forty or forty-five feet because the ships were getting larger, the big container ships, but there was some rock formations down at the mouth of the river and the Army Corps of Engineers told me that it would be difficult to get any money to blast that because of the fishing. The commercial fishermen would object. Well, I couldn't see how this would hurt the commercial fishermen because they go out further to sea. I understand it has been approved, and they have gotten the money from a federal grant. The blast will deepen the harbor and that river, and that means we should have a lot more business coming. One other main addition I wanted was a cold storage warehouse so we could ship a lot of the seafood, turkeys, and chickens from North Carolina through the port of Wilmington.

I reached the age of sixty-five and had been told I must retire in June, 1985. I didn't like the idea at all. I still felt very young and I think it was a mistake for me to be asked to retire. I thought it was a mistake but I didn't fight it. We had just gotten in an area where I had the contacts and I was on many international committees. We had the Australians and New Zealanders, the Japanese and the Taiwanese, all working well hand in hand with us. The Germans, the Italians, and even the Dutch, but most certainly the British, were well aware that we had ports in North Carolina.

In summary, it was a great eight years and next to the Navy it was about the finest I could have of done, I think, as far as finding satisfaction from it. I would have felt better if I had gone on and gotten a doctorate in education or in international affairs. Anyhow, the State Ports Authority was great experience. Virginia and I got a chance to travel a lot. She always made a point to talk about her Alma Mater wherever we went, dear old East Carolina.

H.A.I. Sugg:

What's the situation with the Ports Authority and the Ports now?

William M. A. Greene:

I understand that the money has been granted for the blasting of the rock at the mouth of the Cape Fear River. That will allow them to dredge that to forty to forty-five feet and make it much better, more competitive. We still have Charleston to deal with. Charleston is nearby, and Charleston is growing and growing. They've bought more property and brought in more container cranes--larger staff, larger marketing. Very frankly, I was disappointed after I left that the office in Japan, which I had opened, was closed. The one in New York City, which we had down in the Battery, right near the World Trade Center, was closed. I resented it and went to tell the governor. Now, I do understand that Wilmington should grow. Morehead City is doing fine. The phosphate shipping from

Aurora, which used to be the Texas Gulf Company, now another name, is good. Also, the wood chips are going out to Morehead City to Japan and China and Europe. You see, as we have more computers in use, they need more paper, so that's good. Particularly Japan is buying a lot more wood chips for the making of paper.

H.A.I. Sugg:

The law of unanticipated consequence.

William M. A. Greene:

Morehead City is in a great situation.

H.A.I. Sugg:

They've been deepening the channel there, have they not?

William M. A. Greene:

Yes, they deepened it to forty-five feet and that's good. That helped the big bulk carriers in particular, carrying wood chips and phosphate. They need a lot of water because the ships are so much larger and have a deeper draft. So, that's the Ports Authority.

Morehead City is also a strategic port in that it is near Camp LeJeune and Cherry Point for military deployment.

H.A.I. Sugg:

I remember when I was Phib Group 4 staff, they used to load Marines and equipment out of Radio Island.

William M. A. Greene:

Yes. We did the same thing with Admiral Ormond's Phib Group 4.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Looking back on your Navy career, go back a little ways. First of all, did you, in any of your commands, have female Naval personnel?

William M. A. Greene:

No. I don't know how I would have handled it, because I am so anti-women aboard ships with men. I am just amazed how the commanding officers handle it now. I think it is wrong. I think women should have the opportunities to serve in the Armed Forces. They are good women . . . Naval Academy graduates . . . but I was against women going into the Naval Academy. I really barked about that. But I was told, “Look, Admiral, the decision has been made and you are not involved.”

I am advised in confidence by a number of young gentlemen who have graduated from the Naval Academy that it is really a hindrance there to what they call a “focus.” Although I know one young man who went to the Naval Academy and married a lady he met at the Naval Academy, one of his classmates. They are going to sea now, both of them, but in separate ships, so it's an interesting life.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Do you know Tom Leahy, Ed Leahy's son?

William M. A. Greene:

Yes.

H.A.I. Sugg:

He graduated in 1993 and went into the Marines and he's been going with a Naval Academy classmate, an attractive young lady. Sooner or later that's going to become permanent, I'm sure. I have heard a lot of pros and cons, and the lack of “focus” you just mentioned in connection with the Naval Academy has also been mentioned in connection with shipboard duties, where there are failures. Two other things I get from reading and talking to a few people still working is that first of all, there are certain things that are limited because of their [the women's] lower physical strength. I noted in a recent report that they now assign four people to a stretcher, because it takes four women to carry a stretcher. Also, the pregnancy rate is significant. The problem is that a gal gets pregnant and goes ashore after a certain point to finish out her pregnancy, and that just leaves an empty billet that cannot be filled. It puts a burden on the rest of the ship.

William M. A. Greene:

Well, I will say again that I resent that. I want women to have their opportunities. I am strong on women in our United States government, and I think they are more detailed and more apt to be loyal to an oath than a man. I'll say that with all sincerity. Militarily, we've got to remember, out in sea, everybody has an assignment or many assignments, and being distracted from them is likely if we have a mixed ship's company of women and men.

If we want to have a ship with women only, I would say we should have one without a lot of lifting. I'm probably in a minority and an old “fogey.” My dear wife calls me that. I say, “Well, how would you like me to have gone to sea for six or seven months with women in the same ship? I had enough trouble keeping my eyes off women when I got ashore.”

H.A.I. Sugg:

Hard to beat that argument. Another subject of interest, if you have any comments on, is the subject of leadership, going back to the “Tailhook scandals” and some of the subsequent scandals that are of a similar nature that we've had. What has been charged and what seems to be a failure on the part of the top leadership to take the responsibility that they should?

William M. A. Greene:

The “Tailhook” incident, which is familiar nationally, is a very unfortunate incident for the history of our Navy. I feel that they were wrong, in particular whoever was in charge there, especially with the heavy drinking and letting them have mixed company. I've seen officers and I've been part of the group that celebrated, particular after having been to sea for a while. One's behavior is not necessarily that of an officer or gentleman sometimes. I think it was invited by the person in charge and whoever let ladies get involved in there with all the drinking going on. They should have said, “We came here to talk and hear the young pilots talk about what is going on now.” I blame the leadership for letting it get out of control.

H.A.I. Sugg:

One thing I noted, especially, was that the Chief of Naval Operations was there and, according to the newspaper reports, he said he hadn't noticed anything out of line. This seems to be to me sort of a recurring situation where the top leadership of our Navy and other services fail to lead--to take responsibility. Maybe I'm taking an unduly pessimistic view of things.

William M. A. Greene:

I've heard these reports too. I cannot support them other than having heard them. I know we do have good strength in our leadership now. I'm real proud of our present Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Johnson. I'm proud of the work we're doing in development and what we're doing at sea. I know you can control these things but I'm not saying, “Look what I did.” But I will say this, we had a recruiting command seminar at Ohio State University at which I wanted to get all the officers together for a week. Because it was the end of the draft, we had to put something together in order to overcome this situation that we were all of sudden forced to be real good sales people. We were given just the finest entertainment by the city of Columbus, Ohio. We stayed at Ohio State University on the campus. We kept the drinking under control, because we were there to work. We did have fun in the evenings, because each night we were entertained by somebody in Columbus. But again you can keep those things under control. I hear that some of our people are leaving now and I've seen articles written in the Naval Institute Proceedings that we don't have somebody at the top fighting for us. Those were her words in the article.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Well, I think that's right. Admiral Larson at the Naval Academy seemed to me to be a very fine gentleman who was doing a very fine job with trying to change the situation at the Naval Academy with respect to duty, service, and honor, which we learned when we were in the Naval Academy. He did a tremendous job there. I think it's going to show a definite response throughout the service.

William M. A. Greene:

By the way, I heard the present superintendent of the Naval Academy at the Naval Institute meeting in April speak to the alumni. He said in so many words that he's trying to carry on now what Admiral Larson had gotten people to understand--what the code of the

Naval Academy midshipmen is. He said, “We're trying to make it stick.” I know Admiral Larson and his trouble. He was about to be retired and I understand he asked to come back to try and straighten up some of the slippage.

H.A.I. Sugg:

In your general service you've mentioned some commanders at various grades that you found very impressive. Is their any single individual that you think of that is perhaps the finest leader you served under?

William M. A. Greene:

That's awfully hard to answer. Admiral Burke, of course, our Chief of Naval Operations and also the president of the Naval Institute--I worked closely with him because I was the secretary and treasurer to the board as well as being the editor and executive director of the staff. He was probably the most dynamic person, seeing as he was a quiet type person except behind closed doors. My opinion of a person is genuine whether it be John Davidson, the superintendent of the Naval Academy when I was with him for two years. . . . The best as far as training was concerned was my skipper, Sheldon Kinney, aboard the MITSCHER. The one person above all . . . I wish I could single out one person that I would go back and solicit.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Perhaps you are fortunate that you're not able to make a clear distinction among several outstanding people.

William M. A. Greene:

I think so. I believe I am fortunate there because I had so many of them. It's interesting that my selection board for flag rank was made up of people who I had worked for or with whom I had served in the Naval Academy. Among those was Admiral Bush Bringle, an aviator, who had been a commandant of midshipmen when I first went there as editor of the Naval Institute Proceedings and aide to the superintendent. Charley Minter (?), who later was the commandant of midshipmen and then superintendent, lives in Annapolis

now. A fellow named Doc Abbot and another named Bill Sweede had been executive officers back at Bancroft Hall.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Doc Abbot was a classmate of mine.

William M. A. Greene:

Those people--looking back--did so much to us as role models each in their own way. Bush Bringle was not quite an administrator, but what a leader he was!

H.A.I. Sugg:

That was what was said of Admiral Halsey--not much of an administrator, but what a leader.

William M. A. Greene:

According to the book I read of him, Admiral Mitscher had a heck of a time with him. You know he left he Naval Academy one time, because he was told to go home. He wasn't making it academically. He was reappointed and he went through but he didn't graduate number one in his class. But what a man at sea!

H.A.I. Sugg:

He was a classmate of my late father-in-law. The destroyer I was in during the war worked for him for a long time in the South Pacific, and later when we started the thirty-eight/fifty-eight rotation between Halsey and Spruance, we could see two completely contrasting styles of leadership. With Halsey, you were never quite sure if you would get fueled or not, but it was fun going there. With Spruance, everything was planned out and went exactly as scheduled, and you knew you would get everything right on time. Both of them were outstanding leaders, but they had completely different styles.

William M. A. Greene:

Admiral Nimitz, if you remember, was the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet. He went out soon after the Pearl Harbor attack and took command. I think his predecessor might have been given the shaft a little bit, by what I've read. Pearl Harbor has always been frustrating to me because I keep wondering how did it happen. In the early years I said, “How could we have let the Japanese come in and bomb the dickens out of us?” We had

patrol planes out and we knew there was some uncertainty. I've heard stories that Mr. Roosevelt didn't tell the Navy what he knew was going on. That's not true. I can't believe that of him as Commander in Chief of the military or as President. It is hard for me, and I've made many speeches about it. I've even looked up all the references I could find to see if we could really have stopped them. I can't say I would have done better at it, but I can question why did we get caught.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Well, one of the problems from my study of the history of it . . . Admiral Kimmel was short of long-range patrol planes. B-17s had been coming out and MacArthur, out in the Philippines, had managed to get all of them sent to the Philippines, leaving Admiral Kimmel and General Short without long-range patrol capacity, which was one of the factors surely. Of course, ten hours after Pearl Harbor, MacArthur's B-17s were bombed on the ground by the Japanese. He lost his whole air force on the ground.

William M. A. Greene:

From the books I have on Pearl Harbor I've determined that Kimmel was short on patrol craft. It is documented that he requested more patrol craft, but did not get them.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Well, that was a shock, certainly, and it shook us out of our complacency with respect to our neighbors in the Pacific . . . for example, Japan.

William M. A. Greene:

Think what we've done since that time. I went out on trade missions and only one time was I questioned about World War II, and that gentlemen almost took advantage of me. I had made the determination that he was once a member of the Japanese Navy. At no time in talking to high-level executives did World War II come into the discussion. It was hard for me to bring myself to this part of the century, just remembering how I really hated the Japanese during World War II, given the fact they had sneak attacked us like that.

We will just have our own private beliefs on whether or not we could have stopped it. I think we could have, given adequate support. You and I know that support is next to people in being the number two element for a good defense. Support those who are responsible for our defense.

H.A.I. Sugg:

What year was it you were married?

William M. A. Greene:

1944.

H.A.I. Sugg:

You went through a good many years in the Navy as a married man with a family and children. I see by the current reports and discussion of our problems with recruiting and with people leaving the service that there are problems with family life, which is a major concern. In your experience, you were overseas for long periods of time, how did you cope with this separation, you and Ginny?

William M. A. Greene:

Ginny is and was a remarkable person. She knew what to expect when I decided to apply for a permanent commission, knowing that I was going to be a line officer and would go to sea. That was my preference--I wanted to go to sea and she understood that. I have seen the tears, and I've seen the moments come when all of sudden she had to be in charge of all things--not only be a mother, but also a father and pay the bills. As you know, the plumbing and electrical and the car go out about the time the husband goes to sea.

One time she was left in Hawaii, my first short term as an executive officer of the NICHOLAS, and I didn't realize I had left my family without money. I was gone to join the NICHOLAS on patrol off of Korea for several months. It turned out that a fellow officer had gotten some money for a thesis he wrote in graduate school. He had been in Hawaii in submarine service. He loaned her a hundred dollars out of this money he had received for reimbursement for expenses for the thesis preparation. I didn't know that until I returned

home. She was good enough not to even tell me by mail for fear of worrying me and detracting me from my concentration or focus.

She was just a genuine person and there were some other wives that were also. The younger ones had to be taken care of sometimes. I know Ginny would have a little tea or coffee and would have them come over and just talk and cry. She would go help them with their sick children. That had happened, too, when we were in the junior ranks and senior wives and captains' wives and executive officers' wives would be on hand.

She really deserved what I gave her on our Fiftieth Wedding Anniversary and that was a big heart on purple and gold, and a blue streamer around her neck. It said, “Commitment from 1944 to 1994.” I said, “This has got to be your decoration. You haven't received those things like I have so here is yours.” That was in front of a large crowd of people. Boy, they just stood and applauded. “I decorate you with the heart of gold, and the Purple Heart--a 'Heart of Gold.'” That was the long answer--at least a sincere one--and you can believe it.

Now again we are a product of society. How many of the wives today of Navy officers or naval men came up in homes where they were taught that we have to have sacrifices along the way? I think so many of these young folks in their twenties and thirties haven't had to sacrifice. The economy has been great and they've had everything they've asked for. They have their own room perhaps and everything they want in the room. That's probably the reason we're having many of those troubles now with wives being left at home.

H.A.I. Sugg:

How about your children? You mentioned you wanted to be in one place for Bill, I think it was.

William M. A. Greene:

Yes, our son Bill. His situation was that at the time for him to go to high school I was reaching flag rank level and was shipped around two or three times as young flag officers are. We moved him from three different high schools his first two years and we tried a private school and for half a year. He didn't have the continuity of friends and that's important to young men. That was one of the reasons I listened to the man who said he had a big checkbook and a great opportunity for me for the next ten years, so he [my son] could go through one high school.

H.A.I. Sugg:

How about Caroline?

William M. A. Greene:

Caroline had two years at Fort Hunt, near Alexandria, Virginia, which is a very fine high school. Her last two years were at a private school in Honolulu, Punahou, which was founded many years ago by the missionaries.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Outstanding school.

William M. A. Greene:

She's going out for her twentieth reunion of the Class of 1979. She was graduated there this month. She excelled. It was difficult for us to get her in, but, again, Ginny waded right in. She told the head mistress that she wanted her daughter to go to this school--that “she's capable.” We had already applied before we ever left Virginia to go out to Hawaii in 1978. There was no room because they were filled. Ginny said, “You don't have all students like my daughter. I want her to get a chance.” They asked her to come in and take a test. She went in and the question was to write a five-hundred-word essay on “To Bend or to Break”. Well, Caroline waded into the subject, and the women came out and said, “You've got the smartest daughter. She was admitted and did just great. In fact, she learned the customs there and started wearing what are called muumuu's like the Hawaiian women. She learned their music and their culture. She led the class in singing the state song at their

graduation ceremony. I missed that, of course, being in Vietnam. We were so proud that she did well and were proud of what she did at East Carolina. She went to the School of Music and returned and got another degree--a graduate degree--in music. Now she is the supervisor of music in the Chesapeake Schools in Chesapeake, Virginia. She is doing well.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Lovely, talented young lady as I know.

William M. A. Greene:

Yes, we're very grateful for her talents.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Do you have any general comments that you would like to make about your Naval career or about people or events or anything else?

William M. A. Greene:

Yes. I would go back to the beginning and with hope that somewhere along the way what I have had to say about East Carolina can expand into the appreciation of others, and for the students, of what was done for me.

[TAPE 2. SIDE B.]William M. A. Greene:

My mother, as I have said earlier, had been left a widow at age twenty-eight. She remarried to one of the teachers at Crossnore High School. Thirty-five dollars every three months was pretty high for us to pay as a family, plus she had two other children that needed some help. I was given work [at East Carolina]. In fact the best job I had there was working for the assistant registrar, Miss Ola Ross, right across the hall from the President's office. That included looking after Wright Auditorium, well it was Austin Auditorium, and keeping the grades of the students in order . . . the cards. I was just given such an opportunity, not only work, but also the faculty members who wanted to help me. At the time I went into the V-7 Program, I got to take courses other than my major, which was business and physical

education. We rigged a course of geography out of the Bowditch Navigation--the faculty did. The latter part of my junior year and all my senior year I was taking courses in mathematics and whatever would be best suited for the Navy's needs. They did whatever they could do to keep me above a “C” average because otherwise I was going to be ordered to duty in a boot camp somewhere. But East Carolina has been great since then. I was an Alumnus of the Year in 1963, when I put that missile destroyer in commission. I was inducted into the Athletic Hall of Fame in 1992, I think it was. I am very grateful and of course that's where I met my wife.

H.A.I. Sugg:

Well, that adds luster to an otherwise good situation. I think this has been a valuable interview. I hope you don't feel I have interrupted you too much.

William M. A. Greene: