| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #159 | |

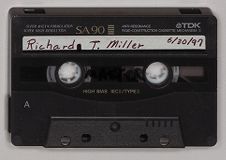

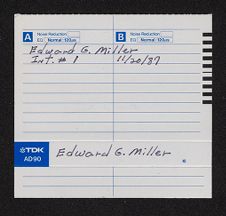

| Captain Richards T. Miller, USN (Ret.) | |

| Graduate of MIT | |

| Honorary Member of USNA Class of 1941 | |

| June 30, 1997 | |

| Interview Conducted by Don Lennon |

Donald R. Lennon:

Can you tell me about your relationship to the Class of 1941.

Richards T. Miller:

Well, I'll go into a little bit about how it happened chronologically later; but I had twenty-eight years in the Navy, and I ran with the Class of 1941 for all those seniority purposes. I was a Reserve officer during World War II, and then I transferred to the regular Navy after the war. So, I had a lot of good friends in the class.

In 1983, I lost my first wife to cancer. Not long thereafter, a member of the class and his wife, with whom my first wife and I had traveled quite a bit, Leslie and Mac Nicholson, indicated that there was a lovely widow of the Class of 1941. They thought maybe I should meet her; they thought it might be interesting.

Shortly thereafter I had a call from another Navy friend, Marty King, the wife of Admiral Randy King with whom I had worked in the Bureau of Ships. She said that they were going to have a New Year's Eve dinner party; this was New Year's Eve 1983, and they requested for me to come and bring whomever I wished. I immediately called Les

Nicholson and said, "Do you think that Alice Houghton would be my dinner guest or my partner?" So Les called Alice, and Alice said that it would be kind of nice. A couple of days later, Les let me know that Alice, who lived in Washington at the time, wouldn't come down if it was snowing or sleeting. She was to stay with the Nicholson's for New Year's Eve. I immediately called and introduced myself over the phone and asked Alice if I could come and pick her up and bring her down, which I did.

We hit it off, and it was just wonderful. The following spring, we finally decided that we would like to get married. We each had two children, so we checked with the kids. They thought it was wonderful, and so we were married in May of 1984. Shortly thereafter, the class decided that they might lose Alice, so they made me an honorary member. So, that's why I'm an honorary member of the Class of 1941. I have thoroughly enjoyed that relationship. It's been a fantastic part of my life to be with these people and enjoy football games, reunions, dinners, and so forth.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, I have known quite a few of them now for quite a long time myself and thoroughly enjoyed it.

Richards T. Miller:

They're a great gang. A number of them have interests very similar to mine. Bob Hayler is an ardent sailor and a member of the New York Yacht Club, as am I. Mac Nicholson, I don't know if you have met him or not.

Donald R. Lennon:

I have met him, but I have not had an opportunity to work with him.

Richards T. Miller:

He is another one you should interview, because he has had a fantastic career. He was an engineering duty officer as I was and an ardent sailor. In fact, my first wife and I sailed down the Inland [Coastal] Waterway with them--from here down to Jacksonville

one year. We also traveled to Greece and Japan together, and we've seen an awful lot of each other. That's how I got connected with the Class of 1941.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now that we have covered that, if you will, let's go back to your earlier days--your childhood. I know you were born in Pennsylvania and reared in D.C.

Richards T. Miller:

I was born 31 January 1918 in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, which was a small town then, north of Philadelphia. The house where I was raised was just a block away from my paternal grandparents. Grandpa Thorne is described in the notes I left with you. He was an engineer. My father was trained as a chemical engineer, but he was first with the Warneret Roofing Company up in Philadelphia and later transferred to Washington.

My early years were just pleasant growing up in a small town. I have no vivid memories other than strawberry festivals, snow in the winter, and trains in the backyard. We were two blocks from a big marshaling yard of the Reading Railroad. I loved trains. I can still hear the chuffing of the steam locomotives, and the whistles and the bells. In those days to get into Philadelphia, you had to take the steam train in. It was always exciting at Christmastime to go into Wanamakers to see the train sets and to travel on a steam train.

In 1927, Dad was transferred to Washington as manager of the Washington office at Warneret Roofing, and we lived out in Chevy Chase. If you recall, 1927 was the year Lindberg flew the Atlantic, and all of a sudden, aviation became very important and interesting to me. Also, I was intrigued that the house my parents bought in Chevy Chase had apparently belonged to an engineer with the Bureau of Standards who was an expert in aircraft structural materials. They were still using a lot of wood in those days and

there were test beams up in the attic, which he had apparently salvaged from some experiments, that were actually milled out like "I" beams.

Donald R. Lennon:

And he had them stored in your attic?

Richards T. Miller:

Yes. He had them plus a whole pile of aviation magazines stored in the attic. At any rate, I became very interested in aviation.

In 1928, I was in the sixth grade, and there was an organization called the D.C. Model Airplane League, DCMAL. If you could build a little bamboo and Japanese rice-paper, rubber-band powered airplane that would fly a hundred feet, and your shop teacher would testify to the fact that you'd done it, and you sent in a quarter, you were suppose to get a set of DCMAL bronze wings and be a member of this organization. I went through all those hoops and sent in my certificate and request. I came home from school every afternoon and asked, "Mother is there a letter for me yet?" It never came. I don't know to this day what happened, but I never became a member of the DCMAL.

Donald R. Lennon:

I built many of those balsa wood and paper models myself.

Richards T. Miller:

Right. So at any rate, I began to lose interest. Then in 1930, Tommy Lipton came over and challenged me for the America's Cup with his SHAMROCK V. It also happened that we had a neighbor behind us who was a naval constructor.

To digress a moment . . . do you remember the fact that the Navy had a staff core of naval architect constructors up until 1939; the Bureau of Construction Repair? They were a group of officers who were called naval constructors, who had studied naval architecture primarily at MIT. A few of them had studied . . . earlier ones had studied abroad. The insignia of the corps was two oak leaves with an acorn in the middle of it.

As I say they were a staff corps. Andy McKee was a lieutenant commander then and an expert in submarine design. He was also fascinated with sailing yachts. He built a model of the J-boat, the type that was racing for the America's Cup in those days, cut out of tin cans. It was about three or four feet long. He invited me to go with his son and him down to the Reflecting Pool for the "test sail" of this lovely creation of his. He also had some old yachting magazines, which he gave me. So I became hooked on boats, and that's where my interest really started.

In those days, I was active in scouting and was a member of Troop 54 in Chevy Chase. In 1929 I went to a YMCA camp because I wasn't old enough to go to the Scout camp. However, in 1930, at age twelve, I became a Tenderfoot Scout. From then on until I went away to college, I went each summer down to Camp Roosevelt, which was the District of Columbia's summer camp down on the Chesapeake Bay. For my last three years there, I was a counselor, teaching rowing, canoeing and sailing. I built my first boat when I was about eleven years old. It was a little double-ended affair made out of scrap lumber that I managed to find. I covered it with one of my mother's good bed sheets and paraffin. It was about five feet long, double-ended, and had an outrigger for stability. My father then took me up to a stream north of the District, way out in the country. I think I floated for about five minutes before I hit a snag and tore the covering. That was the end of that venture.

When I was a sophomore in high school, I built my first real boat, a fifteen-foot snipe. I raced it on the Potomac River in the Potomac River Sailing Association while I was in high school. Then when I went away to college, I sold it. My interest in boats

developed into a very strong interest in wanting to design yachts, and this really came to fruition when I was a sophomore in high school.

My parents, in addition to Andy McKee, had another friend, Ross Daggett, who then was a lieutenant commander and a naval constructor. This was during the Depression years, if you can remember. I knew of MIT, because that's where the naval constructors went to study naval architecture. Rather gently, my father told me that there was no way we could afford MIT.

Ross Daggett said, "Well, Dick, what you should do is go to the Naval Academy and then apply for the Construction Corps, go get graduate work at MIT, and learn that way." But, I thought that was a long way around the barn to become a yacht designer. I didn't want to be a naval ship designer; I wanted to be a yacht designer. So, I did the next logical thing, I think. I went to the yellow pages to see if there were any naval architects in Washington. There was one back in those days, amazingly just one, who had an office located at Eighteenth and Pennsylvania Avenues, in a big office building across from the State War Navy Building.

I went down to see him and he said, "Oh, I think I have the answer to your problem." He pulled out an article written by Admiral George Rock, CC (Construction Corps), Navy retired, comparing the curriculum at MIT, the University of Michigan (which I didn't know about), and the Webb Institute of Naval Architecture in New York City. So I immediately wrote to both of those schools to find out what was available; and Webb Institute was the answer to a maiden's prayer. At that time, if you could gain entrance, there was a full scholarship, with everything paid.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow!

Richards T. Miller:

Your board, room, books, everything.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, was it a state institution?

Richards T. Miller:

It was privately funded, and it still is a privately funded institution. It was founded by William H. Webb, who is a very successful ship builder in New York City. I think he is a better ship builder than Donald McKay, whom everybody thinks of in terms of the clipper ships, because he [Webb?] built some beautiful clipper ships himself.

Webb was a very successful businessman. He had learned the art of shipbuilding as an apprentice in his father's yard. At that time, there was no institution in the U.S. that taught naval architecture as a discipline. I think there were schools in France, Germany, and Scotland that taught it. So, he decided to found a school for teaching young men the art and science of ship design, and it was founded in . . . I think the first class graduated in 1898. I'll have to check those dates for you. But, he opened it up as Webb's Academy and Home. It was interesting, and I think it came out of his experiences as an apprentice. Two things: He wanted to make it possible for old ship builders who didn't have the where with all for a comfortable life after their working years, to have a place to come and live.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was a retirement home . . . ?

Richards T. Miller:

It was a retirement home. And, I think he felt that they might impart some of their knowledge and so forth to the youngsters. The original school was designed and built precisely as the school up in Bronx, New York. By the 1930s, the charter had been changed. They were no longer taking old ship builders in, because it didn't turn out the

way he had hoped. There was no rapport between the old folks. But into the early 1940s, there were still a few of the old people living out their lives there. The interesting thing is that if the person was married, the wife came too. Also, if she survived him, she stayed. When I was at Webb, (I'm jumping a little bit, because I did get to Webb) there was one old lady there that we always had to pass the time of day with. I don't know when she died, but she was there when I was there.

At any rate, as a sophomore in high school I learned about Webb Institute, and of course, I set my sights on that immediately. It took me two efforts to get in. In those days there were maybe a hundred and fifty applicants a year, and even today they only take in about twenty people a year.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was getting ready to say it wouldn't need. . . .

Richards T. Miller:

It's a very small school, a very small school. In those days, the faculty put together their own entrance examinations. You were encouraged, although it wasn't mandatory, to go to the school to take the exams. And it was three days of two three-hour examinations a day in Algebra, Plane and Solid Geometry, Trigonometry, Physics, and English. At the end of the three-day session, a few young men would be asked to stay on for interviews. Out of that group, they would select the final class. Well, of course they had to look at any exams that came in from people who applied to take them at their home school, and one of my classmates did that. He was from the Midwest. I graduated from high school in 1935, and I went right up and tried, but I didn't make it.

I got a job as an office boy in the Association of American Railroads. I found a tutor in the cram schools that flourished in Washington back in those days, getting people

into the Service Academies. I was fortunate enough to find a gentleman who would take me at night, while I was working. I just manned the board for a couple of hours three or four nights a week, then he gave me a lot of work to do at home--working problems. So finally in 1936, I went back up and was selected. I became a member of the Class of 1940 at Webb.

We had nineteen people in my group, originally. Two dropped out freshman year, and one dropped out our sophomore year. We graduated with sixteen. Those years, of course, were years of turmoil in Europe, as you well know. The head of the school was Admiral George H. Rock, naval constructor, retired. He recognized that the situation was deteriorating, and so he worked with the Bureau of Construction and Repair to establish a lecture series. My class was the first one to be afforded this. Twelve one-hour lectures during our senior year on what a naval constructor was and did, what your duties would be, and your responsibilities, and so forth. Having completed that, making an application, passing the physical, and graduating from school, you could get a commission as an ensign cc (construction corps) vs (volunteer special) USNR. And that I did!

Donald R. Lennon:

You decided to put your yacht construction on hold for a while?

Richards T. Miller:

Well, no. No, this was just a commission. As a matter of fact I didn't go into the Navy. I was on inactive duty, but I had the commission. Actually, my yachting was somewhat on hold; because I went to work with a firm of naval architects who had been yacht designers, but their specialty was tugboat design when I joined them. They were designing tugboats for the Moran Towing Company, primarily with the backing of General Motors Cleveland Diesel. So, I went to work the summer of 1940 for Tams, Inc.

About August, I received a very polite letter from the Bureau of Navigation, which was the predecessor of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, signed by a gentleman named Nimitz. It stated that the Navy had a great need for young naval constructors. Since I had a commission as an ensign cc, vs, USNR, would I please ask for active duty . . . and to name three naval shipyards that would interest me? They would try to give me my first choice. I was then engaged to my soon-to-be first wife. She wasn't all that keen on the idea, but I thought that I better do it. So I asked for Brooklyn, Boston, or Philadelphia. I got Brooklyn Navy Yard. Jean lived in the Bronx, right around the corner from Webb. I had found a room up there when I went to work for Tams in New York City.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just the slightest digression . . . is Webb still in the Bronx?

Richards T. Miller:

No. It was a beautiful sight, overlooking the Harlem River on Fordham Road, and they had about four or five acres or more, I guess. Around 1947, the Board of Trustees and other people involved recognized that it would be a good idea to have it moved. A very fine estate on Long Island came on the market, the Pratt Estate. One of the senior members was a neighbor of the Pratts, and he arranged for the school to buy that property. They sold the Bronx property to an insurance company. Today Webb is still out on the Island. It is not quite as generous a situation now as it was for us. It's still free--the tuition is free--but I don't know about books and so forth. The students do pay board and some small fees. I think it was listed as the best buy in colleges in U.S. News and World Report this past year.

Donald R. Lennon:

Interesting.

Richards T. Miller:

It has a very strong technical reputation. It's fully accredited by the State of New York. What's interesting is that it's a four-year course. My degree was a Bachelors of Science in Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering; that is the degree that everybody gets. Back in the 1950s, I guess, the effort was made to establish a graduate school. In fact, the Navy began sending some of its PG students in naval architecture to Webb, and that lasted for several years. There's an interesting little side line on this one: Admiral Bill Brockett was chief of Bureau of Ships back in the 1960s, and he decided that they better concentrate all their PG groups back at MIT. He shut down the Webb input. That really killed the PG school, and so they closed it down. Bill retired from the Navy and was selected to become the president of the Webb Institute. So he arrived there and thought, "Gee, you know, I think we ought to have some of these Navy PGs." He tried to get it started again. He was very firmly told, "Hey, Bill, you shut it down and it's staying shut down." But just in the last year, they have established a postgraduate program again with a Master's and doctoral aims in the marine industry.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't mean to take you off track.

Richards T. Miller:

No, that's fine. Anyhow, I asked for active duty. This would have been in August of 1940. I went on active duty in Brooklyn Navy Yard in late September or early October of 1940. One of my classmates also received a similar letter and all the others did the obligatory "yes" to active duty. However, one of them didn't even respond to the letter. It was about two months later when he got a second letter, noting that he had not responded to the first one, telling him either to write and ask for active duty or to resign and report to the nearest draft board.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh no!

Richards T. Miller:

He got the message, but it cost him a whole year of seniority after the war when he decided to stay in, as a number of us from my little group did.

At any rate, I went to Brooklyn Navy Yard. After spending a boring several weeks up in the planning office going over shipyard regulations, falling asleep at my desk, and having a terrible time, I asked if I could go down on the waterfront and work. I was told that yes I could do that. So I reported down as the ship superintendent in the repair office under a Lieutenant Commander Merit Demerist who was actually a Webb graduate; he had been a tugboat designer of some note in New York. My first few months down there had to do with converting yachts into gunboats, doing repair work on small craft, and things of that nature.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was the Navy buying up yachts?

Richards T. Miller:

Yes, they were buying the yachts and converting them into patrol boats. The most famous one that I worked on was the VERA that had been owned by Harold Vanderbilt. It had been the tender for his America's Cup boats.

One of the jobs I did at that point was supervise the loading of Buckley's PT boats, which were being sent to the Philippines, onto a tanker as a deck load. The ELCO PTs went out from the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, the Brooklyn Navy Yard at that time was making and building a variety of ships; everything from battleships, right on down to PT boats?

Richards T. Miller:

No, no, no, no. The conversions were a variety of small boats. The PTs themselves were being built over in Bayonne, New Jersey, by Electric Boat, which is a

private firm. The only new construction at that time was the battleships. As a matter of fact, I'm getting to that, because I was delighted to be asked to be the assistant host superintendent building the IOWA and the MISSOURI under Lieutenant Harry Englund. I spent about nine months on the building ways, until the fall of 1941.

Several interesting things happened in that period. I can remember in the spring of 1941 going in one day and looking over at the dry dock where the NORTH CAROLINA was being fitted with her guns. There were two cranes lying across the foredeck at the number two gun mount. They had been putting in the lower rotating structure for the turret, which was close to a three-hundred-ton lift. They were using two cranes, sharing the load. These were cranes that had been built in World War I and had been operating in the yard ever since. The cranes had luffing gear to raise and lower the booms that consisted of steel bars with screw threads on them running in a bronze nut. There were no benchmarks to show how much wear was occurring in the nut, but you could see the screw threads that were outside. There was a big power plant just down the river from the yard that had been putting fly-ash in the air for years, and this had just made the best abrasive, and the nuts had been worn by this.

Fortunately, it was just before the turret landed that the nuts stripped on one of the crane's luffing gears and the boom dropped. It threw the load on the other one, and it came down. Nobody was hurt. We were able to ultimately salvage the structure, but it was a terrible sight. With that, we had to go over all of the cranes in the yard, and open them up. All of them were in terrible shape, and they had to be rebuilt very quickly. One of the big cranes was on the old battleship KEARSARGE that had been converted to a

crane ship. I had the job of supervising that effort of opening up its luffing gear and checking it out, on a cold January of 1941, with the wind whipping down the North River; but we got it done.

My main job consisted of me inspecting all the inner bottoms of the MISSOURI when they were being welded up, checking inspections, and following up on our main people. We were putting the lower side belt armor in the IOWA and it was being welded up. I had to run a transit line on the top of the armor once a week to record how the armor was moving in and out with the welding heat so we could make proper adjustments and get those records. It was a very interesting and exciting time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now in the actual design phase, I know at this point in time you were not involved in the early designing, but how did this operate? Was this a team of architects? Did they take designs from earlier battleships and revise them, or did they start from new designs?

Richards T. Miller:

The sequence is that the preliminary designs, conceptual designs, were done in the old Bureau of Construction Repair and in the Preliminary Design Branch of the Bureau of the Ships. A set of contract plans, which were more detailed, also would be produced there. The detailed construction plans were done at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in the design office. They had a very large design office where all the detail plans were developed.

As a matter of fact, I can remember that Captain Haverly or Commander Haverly then was design superintendent, and he had an assistant, Commander Landers. I was up in the office one day going over some plans for some reason or another, I don't remember

exactly, and "Pop" Landers said, "Hey, Dick, look at this." It was the midsection of the battleship and it was the armor I was talking about. "Pop" Landers said, "Look at all this space, Dick. We have nothing assigned here. It's just empty space." By the end of the war, this space was all taken up with electronic gear and quarters, and they actually had people having to sleep out in the passageways. It was remarkable that as it was originally designed, it had a lot of room; however, by the time they had put all the small arms and the small guns for anti-aircraft protection, they didn't have any room. At any rate, I could send a copy of this if you wish.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's on the MISSOURI?

Richards T. Miller:

IOWA and MISSOURI both. They were sister ships.

In the fall of 1941 (September 13, 1941), Jean and I had gotten married and had returned from our honeymoon. The Webb Institute each year would pay a visit, I think it was the junior class, to the shipyard. They would spend a whole day going through all the shops and so forth. I was detailed to accompany part of the group around and be their guide. As we were walking away from the building ways, my boss, Harry Englund, came by and said, "Hey, Dick, we have orders for you to Annapolis, Maryland." One of the visitors in the Webb group was my great old math professor, and he not very kindly said, "No doubt, to teach mathematics, Miller." I was not a star in his math classes.

It turned out that I was not being ordered to the Naval Academy at all. I was being ordered to be Resident Supervisor of Shipbuilding at the Annapolis Yacht Yard. They had just received a contract to build PT boats.

To back up on that one a little bit . . . the Navy in 1939 had a competition among private companies to design PT boats, and they built, I think, four different designs. I used the requirements for the Navy contest as a basis for my thesis at Webb. I designed a PT for my thesis, which we tested in the model tank at Davidson Laboratory over at Stevens Institute. A Webb graduate, who was the senior civilian on the Patrol Craft Type Desk of the Bureau of Ships (out of the twenties), learned about this. He put the finger on me and said, "This is the guy we need down in Annapolis, because (to go back to the Navy competition) ELCO elected not to participate in the competition." Instead of that, they bought a PT from England, from Hubert Scott-Paine, the PT9, and brought it over and demonstrated it to the Navy.

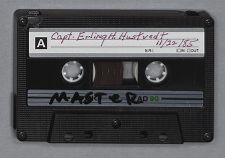

(End of Tape 1, Side A)

Donald R. Lennon:

Building a British design.

Richards T. Miller:

British design, that's right. Well, the president of the Annapolis Yacht Yard learned about this and went over to the Vosper Company, which had a rival design in England. The president bought the rights to build the Vosper boat in this country. His name was Chris Nelson, and he was a MIT graduate and a naval architect. When he got back here, he had a whole roll of plans reported to be of this specific seventy-footer design boat (that's actually the picture of it up there); but instead, he discovered, he had a mishmash of four or five different designs. What he had to do was just go back to the original lines and the basic arrangements and design, do all the detail design to American standards, with American materials, and so forth. That's why they wanted me down to be

the Navy representative: To review the plans as they were being developed and to be responsible for the inspectors that we would have in the yard. I had to look at the ships as they were being constructed.

So I came down here in late September, early October 1941. I left my wife up in New York for three or four months, so she could settle some affairs up there. Then, she came down in January of 1942. I spent the whole war here. The office built up from just me and a couple of inspectors to a full-fledged SupShip's office. At the time I arrived, the Supervisor of Ship Building was actually the officer who was head of the Small Craft Type Desk in the Bureau of Ships and he was double hatted to the job as SupShips. I was his local representative.

In the early summer of 1942, a Captain Hollis Cooley came to Annapolis as the full time Supervisor of Ship Building. We developed into a fairly sizable staff. We had about a half a dozen officers and maybe a dozen civilian inspectors. We acquired yards all around the northern [Chesapeake] Bay area that were building small craft for the Navy: sub chasers, landing craft, and various service craft--barges, and things of that nature.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, many of your boat building works in the Chesapeake Bay area converted to military construction almost entirely during the war.

Richards T. Miller:

Yes, yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

On the construction of the PT boats and other vessels like that, how many companies around the country had these kinds of contracts? Was it a large number?

Richards T. Miller:

No, it was not a large number. ELCO built the bulk of the U.S. Navy boats. Higgins and Huckins also built some of their unique designs, but most of the Navy's boats were built by ELCO. The designs of the later Navy boats were modified in the Bureau of Ships but produced by ELCO. Boats of the Vosper type were never used by our Navy. The "first flight" were for the British, and then we built for the Russians. I think we built about 130 boats there. We were also the lead yard for boats being built by Robert Jacob in City Island, New York, for Herreshoff in Bristol, Rhode Island, and for Harbor Boat out in San Pedro, California. We bought all the government furnished equipment, and we produced in Annapolis a lot of the hardware, struts, rudders, and things like that. We did all the design work there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Boat yards that had these contracts, I assume there were Navy personnel, Navy architects, assigned to each one of the boats.

Richards T. Miller:

We had at least an inspector assigned. Now for instance, one of our biggest operations outside Annapolis was the Owens Yacht Company in Dundalk, Maryland, building thirty-six-foot landing craft, LCVPs. We had a Naval architect who had had his own boat-building business in Louisiana assigned up there as the resident supervisor, and he had a staff of three or four civilians--hull, mechanical, and electrical people.

Donald R. Lennon:

Have you ever heard of Marietta Manufacturing Company?

Richards T. Miller:

Oh, yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

In West Virginia?

Richards T. Miller:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

We just received all of their records. They were brought back in May--all their engineering drawings and blueprints. They made PTs and landing craft.

Richards T. Miller:

I don't think they made PTs; I think they made PCs. I may be wrong, but I think Marietta made submarine chasers and things of that nature. I may be wrong.

Donald R. Lennon:

I thought we saw some PT paperwork in there, but I may be mistaken. But I know they were making a variety of Navy and Army ocean-going tubs, and even ended up making Coast Guard cutters.

Richards T. Miller:

Every shipyard in the country was mobilized to work war production, which goes into a little sidelight. When I arrived at Annapolis, the old yacht AMERICA was hauled out to Annapolis Yacht Yard for overhaul. They were busily removing rotted structure, trying to get down to sound wood to rebuild her. On December 7, we took everybody off. We concentrated on sub chasers and PT boats we were building, and we put a temporary structure over AMERICA. On Palm Sunday 1942, we had a very heavy, wet snowstorm. It caused the temporary structure on top of the poor old hulk to collapse. I wrote a letter to the Bureau of Ships recommending that the yard be permitted to dismantle the remains, save whatever sound wood that might be around, and rebuild her after the war. We would either make a replica or make a model using the good wood.

I received the quickest turn-around I think I ever got from any letter to the Navy. At that time the Supervisor of Shipbuilding was Commodore Swazye, an old naval architect, who had relieved an earlier head of the Small Craft Type Desk . . . Lauren Swazye. The letter back read not only "no," but "hell no!" It said, "You will have the yard put all hands necessary on rebuilding AMERICA and have her sailing by fall." So I

immediately got on the phone and said, "Sir, we just can't do that while we put out the PTs and sub chasers that you're after me about all the time." His response was that "Franklin wishes it so."

Well, we dragged our feet, and by later in the spring, early in the summer of 1942, the War Production Board said that no work would be done anywhere that didn't support the war effort. We got instructions to put a permanent structure over the remains, and there it sat until after the war. At that point, the Navy decided that it wasn't worth rebuilding and they tore it apart. They got rid of most of the stuff. Some wood went up to David Taylor Model Basin, and they built a very lovely model, which is at the Naval Academy now. Some of the wood is incorporated, and in back of you there's a little half model. The black topside is a piece of her keelson and the underbody is a bit of the mahogany from the PTs. The sails are made of long leaf yellow pine from the sub chasers, and the nameplate is a bronze boat nail out of AMERICA. That's my memento of that wonderful, old ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you think there was enough solid wood left in it if you had been able to proceed with it in 1941 or 1942?

Richards T. Miller:

No, I don't think so. It was badly rotted, and it had not been taken care of. It would have been a replica, regardless, with all new wood.

So any rate, I spent the war in Annapolis and enjoyed it very much. We had a great team. I tested all the PTs and the sub chasers and ran the trials. I made delivery trips on a lot of the Russian PTs to New York. The British PTs were taken away by their British crews from here.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, did you run them to New York individually, or did you load them on . . . ?

Richards T. Miller:

No, we ran them up individually, usually two at a time.

Donald R. Lennon:

That would be fun.

Richards T. Miller:

It was. We had some exciting trips. The interesting thing is that we were going year round. In the couple of winters we did this, when there was ice at the head of the Bay, we would go down around Cape Charles, refuel in Cape May, and then proceed into New York. Usually, we would overnight in Cape May and then go into New York the next day. In the summertime, we were able to go up through the Chesapeake and the Delaware Canal, down the Delaware Bay, and on up; we could make it to New York in about eight hours. We'd cruise at around thirty-five knots. I had one boat up to forty-seven knots once on the measured mile on a test run.

Donald R. Lennon:

They handled beautifully, didn't they?

Richards T. Miller:

Yes, they did. But they're a brute at sea. In fact, on a trip in March--and it was one of the first trips up through the canal of that year--we were told that the two boats we had going out had to be up there to meet a convoy. The boats would be loaded on freighters in New York, taken into Murmask, and then they would work their way down through the Russian rivers to the Baltic and to the Black Sea. We were told that we had to get them up there, and it was a miserable, miserable day. There was a Nor'easter. It was sleeting, snowing, blowing, and storm warnings were flying as we rounded Cape May. We worked our way up the Atlantic Coast, buoy hopping; and we took off from Atlantic City Sea Buoy, headed for Barnegat Light Ship. We ran out our time when we should have found it; we didn't see it. This was about mid afternoon. We had had

trouble getting into New York on previous trips because of mixed-up signals getting through the nets.

The boats were still owned by the boat yard until they were delivered to New York, and they had a civilian crew. In the wintertime, there would be the boat captain, an engineman, and a signalman that we borrowed from the Naval Academy, and me or somebody from my office. On the following boat there was somebody else from the SupShips office. I recommended to Cap Cole, and he agreed heartily, that we should go back, get into Atlantic City, and stay the night. We turned around and ran our time down to be off of Atlantic City and headed right for shore. It seemed to me that we were going, and going, and going--not raising anything--and I began to get a little concerned. I got on the radio and called the Coast Guard and identified ourselves, and asked them if they would take a radio fix on us. About the time they said "start sending, and we'll take a fix," Cap Cole yelled out, "Hey, Dick, Atlantic City Sea Buoy dead ahead." So, we passed the sea buoy, and we headed for the Ventnor Boat Works. I went forward with the other hand to get some lines out, opened up the four-peak hatch and looked right out the side of the boat. We had a hole, two frame-spaces wide and the same depth, pounded through the port bow of the boat.

Donald R. Lennon:

From the pounding of the water?

Richards T. Miller:

From the pounding of the water. The problem was that we couldn't live on the boat over about twenty-two knots, and we couldn't steer under eighteen. She just wouldn't handle, and we were just slogging away there at about twenty knots and pounding into this heavy sea.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you could have floundered very easily.

Richards T. Miller:

We were very lucky, and it's a good thing that we turned around when we did.

At any rate, we got into Ventnor. The other boat, which had been following in our wake, had the same incipient problem but not as far developed as ours. The skipper on the other boat was an old Maine fisherman who was a rigger at the yard. We were going up an elevator in the hotel later that night, and this old guy looks around and says, "Iron men and wooden ships."

We patched the boat up in Ventnor and got them in a couple of days late; for some reason or another, the convoy had not sailed. We turned these Russian boats over to Mr. Sidben, a representative of the AMTORG Trading Association, which was the equivalent to the British Purchasing Mission (the Russian equivalent) up in New York. Sibden came down, and he looked at the boat and said, "Oh my God! How long will it take to fix?"

I said, "Oh, a couple of weeks."

He said, "I take the boat." So, he took it the way it was.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, it was just a matter of replacing . . . .

Richards T. Miller:

Some framing. The problem was the collision bulkhead was a hard point, then there was a relatively light frame, and then there was another very heavy frame; and the light frame cracked about mid length and then everything caved in. We did a little redesign, too, as a result of that.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would think that the pounding that you get off of New York would be a lot less than what the Russians would experience up in . . .

Richards T. Miller:

. . . in the Baltic or something. It's hard to tell. The Atlantic can get pretty rough. The other interesting thing is that in the wintertime there would just be the three or four of us on each boat. Come spring, we would start getting calls from Washington, "Hey, Dick, are you still delivering PTs to New York? Love to make a trip with you." And we would have a dozen people on board making the trip.

Well, on some of these trips I would stop back at Tams. Actually, to back up a bit, when I went to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Dick Cook, the naval architect, at Tams asked me if I would do night work, because he had a lot of design work underway. I said, "Sure." So for about a year, while I was at Brooklyn, two or three nights a week I'd stop in at Tams for several hours and he would have things laid out for me to do in tugboat design and propeller design and things like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine they were building tugs for the Army or Navy too, weren't they?

Richards T. Miller:

Ultimately they were.

So at any rate, on one of these trips, Dick Cook proposed, indicated that the owner of the Tams, a gentleman Edgar Offer wanted to get out and would sell the firm to us--really the name and some drawing equipment things like that--for a modest sum. Dick Cook, the broker (the firm was still doing yacht brokerage work), Harry Fair, and I would form a partnership and buy in after the war. So, when the war ended and I went back on inactive duty, Jean and I moved back up to New York with her parents, and I went down all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed to get going on this partnership in Tams, Incorporated. Dick Cook said, "You know, Dick, George Codrington is hovering in the background here somewhere and supporting the old Tams organization." Codrington was the head of

Cleveland Diesel Engine Division of General Motors. "We can't get a clear understanding from Offer as to whether we have clear title to the company or not if we buy in. Harry Fair doesn't want to have anything to do with it. He's dropping out." Dick Cook said, "I'm not a salesman, Dick, and I don't think you are either. So, I'm dropping out." So, the whole thing blew up in my face.

So I thrashed around for about a month. Fortunately, I had three months of terminal leave saved up from the war, so I wasn't out of the Navy yet for pay purposes. I thrashed around for about a month looking for something that was interesting and ended up with the Federal Ship Building Company over in Kearney, New Jersey, in their design office in Newark. I was commuting from the Bronx to Newark every day. The atmosphere . . . and this was in the winter of 1946 . . . and the atmosphere in the office there was just dismal. I couldn't put my finger on it. I wasn't old enough or smart enough to figure out what was wrong, but it was not a happy situation. I did this for about a month and then I called an old acquaintance in the Bureau of Ships, Mike Hunsinger, who later became an admiral, and asked if I could be ordered back to active duty. And Mike said, "Sure. We've got all kinds of work here at the Bureau." So, I received orders back to active duty to the Bureau of Ships to the preliminary design branch, specifically the War Damage Analysis Crew in Preliminary Design. By March of 1946, I was back in active duty.

Donald R. Lennon:

Before we leave Annapolis and the World War II period, you indicated that not only was the Annapolis Yacht Yard building PTs and sub chasers but there were a

number of other boat yards up and down the area that were doing the same thing. Is there anything else you want to speak to on that?

Richards T. Miller:

Well, it was an interesting group. We had the American Electric Welding Company in Baltimore building barges, steel barges; and the Owens Yacht Company, building the LCVPs. We had a little outfit up on the Magathy River, building plane rearming boats; and then we had Bird Boat Company up on the upper end of the Chesapeake, the name of the place escapes me right now. We had Vinyard over in Delaware, building sub chasers in Milford, Delaware; the Seaford Ship Building Company, building wooden barges and plane rearming boats; and the Oxford Boat Yard Company, building picket boats, patrol boats, aircraft rescue boats, and plane rearming boats.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, the Chesapeake was just a beehive of ship construction.

Richards T. Miller:

Right, right. Small, small, small stuff. Also, we had a liaison office at Bethlehem Fairfield, where they were building LSTs for the Navy. I don't think . . . I think Bethlehem Sparrow's Point was building cargo ships. I don't think they were building any Navy ships, and we didn't have an office there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Liberty ships you're talking about?

Richards T. Miller:

Yes, things of that nature. The Maritime Administration took care of the inspection of that type. In fact, the Maritime Administration had primary inspection responsibility for the LSTs, but because they were for the Navy, we had a liaison officer, Tony Sonesca(?), lieutenant naval architect, up there. Incidentally, I have a complete record, which I wrote in 1945 of those operations, if that would be interesting.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was going to get ready to ask you how many Naval vessels you built there.

Richards T. Miller:

I have a listing of all the contracts and all the types that were built under SupShips Annapolis. I'll show it to you before you leave, and then if you're interested, I'll get a copy for you. I also have written an article called, "Naval Boat Building in East Port in the Annapolis Yacht Yard," which goes into a lot of detail about the Annapolis operation.

Donald R. Lennon:

And where was that being published?

Richards T. Miller:

It was published by Chesapeake Maritime Museum--a slightly edited copy--and I can give you a full copy.

Donald R. Lennon:

That would be interesting.

Richards T. Miller:

Yes, I'll get those to you. So at any rate, that's about it on the war years.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you went back into regular duty in 1946 after just three months hiatus?

Richards T. Miller:

Right. In fact, my service record doesn't show any break at all. I was just on terminal leave, which is fortunate. At that point, I applied for transfer into the regular Navy and also for the PG course at MIT, and both of these came through in 1948. I guess 1947 was when I was transferred into the regular Navy and 1948 was when I was ordered to MIT. But during those couple of years in preliminary design, I was writing, finishing up the war damage report, and also doing armor studies for the aircraft carrier, which was started but Louie Johnson killed. I learned a little bit about how you calculate the armor thickness to withstand certain shell attacks and things of that nature. This was very interesting. I first met Admiral Rickover at that point.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was probably a lovely experience, wasn't it?

Richards T. Miller:

Yes. The interesting thing is that some of the stories about Admiral Rickover . . . you know he talks about how the Navy gave him an office that had been a ladies' restroom. Well, it was, or it had been a ladies' restroom, but it wasn't even his office. It was across the corridor from the Preliminary Design Branch of the Bureau of Ships, on the fourth floor, fourth or fifth wing, in the old main Navy building. I think it was Admiral Salberg(?) that had the office and he was planning the Bikini tests, and Rickover had just two desks in that office. Now, Salberg was a real gentleman. He had this little coffee mess and he invited the young officers who were attached to preliminary design to come in and draw a cup of coffee every morning about ten o'clock. We'd do that, and old Rickover would be at his desk just glaring at us because we were going in. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Invading his personal domain.

Richards T. Miller:

Invading that domain and getting coffee, wasting our time getting coffee. I never had any real contact with him except that his senior assistant was then Lou Roddis, who was number one in the Class of 1939 at the Naval Academy and had been a partner of mine in Ms. Wallace's physics class at Western High School back in the early thirties. We used to do our physics experiments together. At that point Lou had been assigned to be an assistant to Rickover and was getting started on the atomic power plants.

Donald R. Lennon:

Most people that I know who had contact with him had very unfavorable reactions to his personality.

Richards T. Miller:

Well, I had a few contacts later that were more personal and equally unpleasant when I was head of Preliminary Design, but we can get into that later. At any rate, in 1948 . . . a little digression . . . in 1947, I asked for and received an unusual set of orders

to become a member of the crew yacht VAMARIE in the first Newport-Annapolis race. The VAMARIE was a beautiful staysail hatch. The VAMARIE had been given to the Academy in 1936 or 1937, by her owner, Vadim Mackaroff, who I gather was the "caviar king" of America, or at least that is where he made his money. The Academy had entered her into the race; so I was duly ordered to be a member of the crew.

We had an interesting trip. She didn't have an auxiliary engine and so a destroyer towed us up through the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal. The POLLARD

Donald R. Lennon:

A destroyer?

Richards T. Miller:

Yes. We left here in the afternoon. In the evening the destroyer was pulling us down Delaware Bay and he was going lickity split--not for him, but for us--doing about ten knots or more. The Delaware was its usual ugly, terrible best: There was a southerly wind, an out-going tide, and a very short chop, and we were getting beaten to death. So, we signaled to the POLLARD to drop the line and we would sail out, which we did. The next day was a magnificent June day and we were on a broad reach going up the Atlantic Coast off Atlantic City. We had a radio going in the cockpit and we had all the sails set and there was a shimmy here and a shake their, but everything was going pretty well. The skipper had been Mackaroff's professional. His name was Axle Trunan; he was a German, and a lieutenant commander, Navy Reserve. He looked around the cockpit and he said, "Vell boys, this is yachting! Coming back, ve vork."

The next day we were in Newport. We had a couple of days up there to get ready for the race and then it was a four-day race back. It was not a good race down the coast because of fickle winds. It really seemed to start all over again down at the Chesapeake

Light Ship. All the big boats sort of congregated there on a late afternoon. We had thunder squalls over the Virginia coast, and the race really started about five o'clock all over again coming up the Bay. We had spinnakers set all evening and we were just roaring along. I came on watch at midnight and the wind had hawed enough that we had to take down the spinnaker and set a Genoa jib. We got into Annapolis about seven the next morning. It was the most glorious sail that I can remember.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you place?

Richards T. Miller:

Eighth. Not to well, but we had a good race. The fiftieth reunion of that race was just held last year. I mean last week. Nowadays, they go from Annapolis to Newport instead of Newport to Annapolis for various reasons.

At any rate, in the summer of 1948, I was scheduled to make the Bermuda race on the VAMARIE, but the day that race started I had to report to MIT for my graduate school, and I knew what my priorities were. So, I reported to MIT in June of that year, 1948. We had a refresher course all that summer to bring us back up to scholastic speed and then the courses started. We were there for three years. It was very challenging and interesting, and I developed a feeling that it was a good idea to have a few years under your belt before you went to graduate school from undergraduate because you learned a few of the things that you didn't know.

Donald R. Lennon:

Particularly in something like you're in--naval architecture.

Richards T. Miller:

Right.

Donald R. Lennon:

You have to have some experience with it.

Richards T. Miller:

So at any rate, the first summer the Navy discovered I had never been to sea in any "real-experience" sense. So, I was assigned with my classmate who had been my roommate at Webb for four years, Vandyke Johnson, as sort of supercargo on the light cruiser ROANOKE on her shakedown to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. We had a very interesting summer on board; qualified for engineering watches and student safety officer and the gun turrets and planned--going back to my war damage report experience-- planned the damage-control exercises for them and things like that. The second summer I was sent to David Taylor Model Basin and had a very enjoyable summer working there.

At MIT my thesis was on the response of a ship (we did a cruiser and an aircraft carrier) to a non-contact under-bottom explosion, which had me cranking out formulas on an old hand calculator--a Monroe calculator--hour after hour after hour. I did that thesis with one of my partners in the PT design from Webb, a chap named Steve Town.

Then I was very fortunate. I had bought a house in Lexington, Massachusetts. It was the first house I ever owned, a very nice little Cape Cod. I had orders to Boston Naval Ship Yard as planning and estimating superintendent out of MIT. So, we were there from 1951 until 1953. Worked for a real fine group of officers.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, the Navy did not do any unusual design or shipbuilding work as a result of the Korean War, did they?

Richards T. Miller:

Yes. One of the things that they did as a result of the Korean War was the crash program in minesweeper design and building. It was typical of the Navy in my view . . . the U.S. Navy is a blue-water Navy, and they aren't comfortable in green water and brown water. The forces that they need for that kind of work just get ignored in

peacetime. And so it was with minesweepers. They had been allowed to deteriorate or been laid up and sold off for World War II. When they wanted to land troops on Wonsan Beach, they were held up for weeks by very crude Russian mines that actually dated prior to World War I in technology, because they didn't have the minesweepers.

Now, to back up a little bit, there had been a program developed by the Small Craft Type Desk in the Bureau of Ships with Packard to develop a low magnetic signature diesel engine, and it was going along quite well, when all of a sudden the cry came out, "We need minesweepers." So this engine was rushed to production long before all the engineering wrinkles had been ironed out, and the ships were built. I became associated with this later on, in 1957 and 1958, when I was on the staff of Mine Force Atlantic Fleet, and we had all these engines that were having a terrible time. At that point they were beginning to solve the problems and were rebuilding the engines and they were becoming fairly reliable. But that was one of the major shipbuilding efforts that came out of the Korean conflict. I think you're right that in Korea . . . because there weren't any strong naval forces arrayed against us . . . that we were able to use what was available in the general sense.

But again, in Vietnam, we had to have crash programs to design craft for the Riverine Warfare, which was foreign to our blue-water Navy. In fact, I have an article that I wrote for Naval Review on that subject, which you might be interested in. It's called "Fighting Boats of the Navy."

All of my duty has been stateside. I've never been outside the States, and every other tour of duty was in Washington, in design.

Donald R. Lennon:

It just occurred to me after the great World War II effort whether they just continued to utilize World War II vessels or what.

Richards T. Miller:

A lot of the World War II vessels were eliminated. For instance, there weren't any PT boats around. They had to go into a crash program to build gunboats for Vietnam. We didn't need them in Korea, but in Vietnam we did.

I don't know how you want to pick up the thread here on my career. We sort of left it at MIT in the Boston Navy Shipyard.

Donald R. Lennon:

There are just a few more minutes on this tape. At Boston Navy Yard you were primarily involved in. . . .

Richards T. Miller:

I was in Planning and Estimating for Ship Repair Work. Mostly destroyers. We had a lot of destroyers come through. We had one interesting incident that relates to the old KEARSARGE, the crane ship that I mentioned I was associated with in Brooklyn. She had been moved to Boston for some reason or other, I don't know why. There had been a trawler, a steel trawler, maybe a 120- or 130-foot, run down by a tanker at the entrance to Boston Harbor around 1951 or 1952 . . . about 1951 I guess it was. A salver from Florida had bought the salvage rights to it. His idea was to raise it and convert it to a salvage craft for his own purposes. He first thought that he could seal the hatches and so forth and pump air into it and make it buoyant enough to come up. To his horror he discovered that although it was a steel hull, it had wooden decks and no way could he seal all those wooden planks. About that time he noticed the KEARSARGE and he thought maybe she could lift it. So he came around to see us and I was given the job to look into it. The first thing we had to determine was that there was nothing else around with the lift capacity

that he needed and, then, that "yes" we probably did have--with the 300-ton lift that she could do--enough capacity to help him out. So the yard arranged a contract with him. He then went out and put straps around, buoyed them, and got everything ready for a lift. Captain P. D. Gold, the shipyard commander, was very concerned though that we might be getting on the edge of the capability of the KEARSARGE, so he instructed Jim Greely, the captain, . . .

[End of Taped Interview]