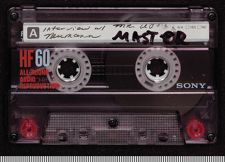

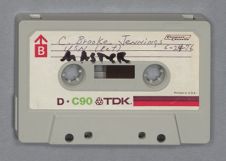

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #24.050 | |

| Leo Neumann | |

| U.S.S. NORTH CAROLINA BATTLESHIP COLLECTION | |

| October 5, 1992 | |

| Interview #1 |

[Interviewer]:

Mr. Neumann, start out by telling us how you came to join the Navy?

Leo K. Neumann:

The Navy was always a lifelong dream--to be in the sailor suit and to be aboard ship and to be overseas, or see other different ports outside of being a poor kid and not being able to get around too much. When the opportunity came when I was about seventeen, I decided to quit high school to join the Navy. Of course, my parents had to sign the papers because it was known as the kiddie cruise. You would be discharged on your twenty-first birthday. It wasn't the full six year enlistment that was required of people eighteen and on up. Being just seventeen, I had to get parent's consent, which they did sign.

[Interviewer]:

What year was that?

Leo K. Neumann:

1941. I was born New Year's Day 1941 [should have been 1924], therefore I was just seventeen and I was inducted into the Navy January 9, 1941. See all the time you thought you were celebrating New Year's and it was my birthday you were celebrating.

[Interviewer]:

Where did you go? Did you go directly?

Leo K. Neumann:

We went through boot camp, Naval Training station, which was located in Newport, Rhode Island.

[Interviewer]:

How did you come to the battleship?

Leo K. Neumann:

After, I believe, it was seven weeks training at Newport and then you receive a nine-day leave to go home. When you went home you spent the nine days; of course, within the nine-day period you had to report back to Newport, Rhode Island. You were assigned to your station.

[Interviewer]:

You report back to your station?

Leo K. Neumann:

You report back to Newport and then we were to receive our orders where we were going to be dispersed. Fortunately, for me being from New York, the USS NORTH CAROLINA was being built in Brooklyn Navy Yard, which I was assigned to it and most of my company was also assigned to it. So at that time, a lot of New York boys were assigned to go on the USS NORTH CAROLINA which I went back to Brooklyn Navy Yard and I was practically home again.

[Interviewer]:

Wonderful. So you got to stay at home for a while. How long?

Leo K. Neumann:

Quite a long time. The ship was commissioned as we know April 9, 1941, and we had various sea trials, after it was worthy enough to go to sea, and back and forth and engineering testing and finally the gunnery testing. We would go to Newport and Hampton Roads. Down the Caribbean to Guantanamo Bay to Kingston, Jamaica, or even Casco Bay, Maine. That lasted until around June of 1942. Therefore all this time we would go in and out of Brooklyn and in and out of these ports. Of course what happened in this time--December 7--happened and we knew the war was on and we were waiting to go to where they wanted us to go, which was the Pacific eventually.

[Interviewer]:

You were aboard the NORTH CAROLINA this whole time?

Leo K. Neumann:

This whole time, yes. We went through the Canal on June 10, 1942. Went to Long Beach, California, then San Francisco. We left San Francisco in July. We arrived at Pearl Harbor July 11th, was it. We arrived at Pearl Harbor and this was the first time Pearl Harbor saw a capital ship of our size and our armament from the States in all that time that them boys were

there waiting for help from the States. It was a fantastic sight. They began to cheer. All the people were lined up along the docks, the yardmen stopped working, everybody saw this magnificent ship coming into Pearl Harbor. All the carnage was still there. The ships being still in their sunken positions. Believe it or not, even as late as July, bodies were still popping out of the water, which was fearful for the people even to work in the water. A lot of times they had a whole lot of trouble to get the people to go down below and see what was going on in the bay itself, in the harbor. It was horrible! This is what we saw. This is what we felt and we couldn't believe how everybody began to cheer when we came into that port. It was magnificent. It was a tremendous, unexpected, and a thrill. Never forgotten by any of us who were there.

[Interviewer]:

Seven months later you were kind of the first sign of home?

Leo K. Neumann:

Yes. We were there more or less. They needed help; they were looking for help and it finally came. We were the forerunners of all the ships that were to come after us, to come to Pearl and that joined the South Pacific forces.

[Interviewer]:

What was your role on the ship? What was your duty station? Your battle station?

Leo K. Neumann:

Alright, we had two different departments actually. The deck force and the engineering force. The engineering force was my duties. I was assigned to PF Division, Number One Engine Room.

[Interviewer]:

So you were in the engineering force?

Leo K. Neumann:

Engineering force which was called the “slang foot” or “snipes”. We were known as “snipes” and the deck force was known as “deck apes”.

[Interviewer]:

Do you know where those nicknames come from?

Leo K. Neumann:

Well, it is traditional navy talk. That is about it. It was picked up and we just carried it on. Of course, we had all kinds of nicknames for each other. We called the “deck apes”

“barefoot on the deck” and they called us “old greasy shoes,” because we came up from the engine rooms and we were supposed to be dirty with oil and things like that--which was quite exaggerated.

[Interviewer]:

Probably all in good fun?

Leo K. Neumann:

Well, it was good fun, but the boatswain mates didn't like the idea of us coming up. They said we greased their bulkheads with our clothes and everything else, which was farfetched, of course. But they had that in their minds. Of course, fresh air was a great thing for us in the engineering force, because you “et,” slept and did everything below decks. When you got up on topside, you appreciate the breath of fresh air. Of course, if you notice people today walking around the ship, they can go anywhere they wanted to go. That wasn't so when you were a crew member. If I was found floating around the brig somewhere, they wanted to know what I was doing there. I'm not supposed to be there. In other words, I had my designated area to be aboard ship and I had to be around there, because that was my life. My life wasn't in the sixteen-inch turret or the five-inch turret or up in the bridge or up in the signal bridge, my life was down below.

[Interviewer]:

How many hours a day and what would a typical day be like for you below? Would you stay down there?

Leo K. Neumann:

Two conditions, if you are in port, naturally it was liberty time. You would have port and starboard liberty. Or three section liberty, which three sections and one section stay aboard. Three sections could go on liberty. Underway it was four hours on watch, eight hours off. Four hours on watch, eight hours off while you were underway.

[Interviewer]:

In those eight hours off, what did you do for fun aboard ship?

Leo K. Neumann:

Well, fun was pretty much up to yourself. You entertain yourself by writing letters. You entertain yourself by listening to someone who knew a musical instrument. Somebody else read a letter of something funny that happened in his family. You would try to keep yourself clean at all times, because a shower was very necessary especially in the Southwest Pacific where sweat was a very common thing. The engine rooms at that time could reach as high as 136 degrees of dry steam heat, which was very, very uncomfortable. You would go down and sweat immediately. The trick was to take a shower, go quietly in your bunk, even though the ship itself might have been a hundred degrees, to go to bed before you start sweating again, to get at least a half hour of sleep before you wake up again from the sweat and everything else and continue on the day. You would go, chow time of course was mealtime. Then you would write letters and entertainment part, you would talk to someone else who you went to boot camp with. You meet them and you converse what their duties was as compared to yours.

[Interviewer]:

You had said that a lot of folks came from the same area. A lot of New York boys. Were there people that you had grown up with that went with you, or people you knew?

Leo K. Neumann:

Only one guy, I knew of. He was in the same high school I was. He was in the bake shop. Now I was fortunate to know him because if anything was left over, he would call up the engine room, “Neumann, send up a messenger, I have some left over pies.” I would send up the messenger, he will come down with the pies and I always had something to eat or leftover. He would make a pie or cake. He would actually make a flat pizza pie and he would send some down to us. He always took care of me like that. We were always buddies in that frame of mind. Of course, later on we got people from all over the United States that came aboard--Denver, Louisiana, California. A lot of boys from Kentucky, Tennessee. Arkansas was a big favorite; a lot people from Arkansas. These people there were more or less the older salts that

were transferred from other ships. They had about six or seven years in the Navy and they were more or less our superiors at the time. When you come out of Navy training station, you are a boot. You are the lowest of the low.

[Interviewer]:

Do you recall that they treated you that way or did they help you out and try to teach you the ropes, or did they teach you the hard way?

Leo K. Neumann:

Well, they would teach you the way they thought that you could grasp it. There was an awful lot to learn in an engine room. If you've been aboard the Number Four Engine Room and you will see what it is all about. All them pipes and lines and valves, they all mean something. Not knowing anything about it, I had an awful lot to learn. If you didn't go at it and swallow it and do what you can with it, you'll never make it. I tried and tried and tried. I wanted this watch to know what that watch was, I wanted to know what the pump watch was. All of a sudden one day I woke up and the whole engineering plant hit me. I saw what it was all about. The whole recycling and cycling period of it. Eventually I knew what every valve in that engine room meant. It was fantastic how it just hit you all at once. If you can grasp the whole situation, it was amazing. Of course, these boys that we knew that were our bosses . . . Mr. Black came off the OKLAHOMA which was capsized on its side in Pearl Harbor. Another boy was off the ARIZONA. He got transferred off the ARIZONA. He was a machinist mate earlier before December 7. He was one of our machinist mates first class, as we call it. And a couple of chiefs off some other battleships. That is how the crew developed into a crew.

[Interviewer]:

Was that your specific title, is that what you were referred to as--a machinist mate?

Leo K. Neumann:

Yes, I was a machinist mate striker. We were known as firemen. The machinist mate was the engine room side where you regulated the steam to the engine room, take care of the condensated water that came out of the engines, the turbines which were steam turbine driven.

Condensate the water and recycle the water back into the boiler. The boiler crew, they are striking for water tender. They knew boilers, they knew to put the burners in the boilers, what size tips to put in the burners, how many burners to put in at certain amounts of speed and then when a change of speed comes to put more oil pressure in and maybe put another burner in because the engine would require more steam to make more revolutions. That was the engineering force, the engine room guy. Two different strikers, one fireman striker for the machinist mate which is on the engine room side and the other fireman was striking for water tender, they were on the boilers.

[Interviewer]:

Which did you do?

Leo K. Neumann:

Engine room side. Take their steam, throw it into . . . The bridge would tell us how fast we wanted to go. I would with this throttle submit the steam a certain amount, to let the revolutions pick up the steam that they wanted. That steam was condensed back into water and recycled through a de-aerating tank which takes all the impurities and air out and pump back to the main feed pump that pumps back into the boiler. It was recycling plant, that is what it actually was. There is so much more to it than that. You had lube oil pumps, bilge pump, fuel oil emergency pump, fuel oil pumps for the boilers and fuel oil heaters because that oil had to be heated at, I believe, 180 degrees. It was a complicated engineering plant, steam engineering plant.

[Interviewer]:

After the Navy, and we may talk about this a little bit more, did you take this knowledge away from the Navy and put it into something else when you got out?

Leo K. Neumann:

To a degree. Once I wanted to be a stationary engineer in New York City, which required a license where you could take care of boilers from hospitals or hotels and things like that. The change became very much so where bigger plants were to be taking care of hospitals,

their power plants were taken away and their power was given by the city. Therefore, the individual power plants for each hospital wasn't there anymore. The power was coming from somewhere else. The type of people that were in that field were quite heavy drinkers. I didn't like that too much. I didn't want to fall into that category. So I left and went to other fields.

[Interviewer]:

You talked about these other folks that showed you the ropes. Are there other people who kind of stick out in your mind, officers that helped you out or other enlisted people?

Leo K. Neumann:

Well, these petty officers that I mentioned are enlisted people, they were from other ships. They had more experience. They had seven, eight years experience as compared to mine which was practically off the streets of the city. It was up to them to teach us. We had books to read, when we made a rate we had to pass the test, of course. It was basically engineering. You eat, you live and you do other things besides that in the same spot. It's constantly with you twenty-four hours a day. You had to learn. You just had to learn. Of course, we had a man called Mr. Maxwell. He came up through the ranks. He was a Polish immigrant. He got into the service as apprentice seaman. When we met him in 1941, he was lieutenant commander. He went up, as an enlisted man, all the way up I don't know because of the war or anything else that he was made lieutenant commander, but he was an engineering officer. He would come down to us and talk to us and say, “Look, as long as I am here, you can call me Maxi, but if another officer comes around you will have to respect the fact that I am an officer.” He was very congenial that way. He talked to us right straight, chest to chest, with no rank between us. He was very helpful in teaching us a lot of things about the engineering plant.

[Interviewer]:

Did you keep in touch with him afterwards?

Leo K. Neumann:

Well, he kept in touch with the ship. In fact, he is very responsible for bringing the ship here, Mr. Maxwell. He died about four years ago or something like that. He had spent his last

days in Brooklyn, New York, too. There is a long story on him in one of our issues of the Tarheel. It's quite interesting, it's very fascinating.

[Interviewer]:

He sounds like a fascinating person.

Leo K. Neumann:

Oh, yes. He was.

[Interviewer]:

Are there other events that stand out in your mind?

Leo K. Neumann:

Well, of course, the torpedoing. That happened September 15, 1942. Everybody remembers where they were. It happened about 10 minutes to 3 in the afternoon. At the time, I was a mess cook. A mess cook is a guy who is in his white uniform and he is up in the mess hall and he takes care of the mess tables and makes sure there is coffee on the tables and sugar and whatever is necessary. Everybody has to go through that in their Navy career. It is three months. You try to get that mess cooking duty in within a year but somebody forgot me and I was an old salt of a year and a half, so I had to go to mess cooking. Of course, when the torpedoing happened I was in my mess white clothing in my bunk. My bunk was between frame eighty five to ninety five on the same deck where the torpedo hit. In other words, it was maybe about two hundred feet from me when the torpedo struck. When that thing struck, it threw me out of my bunk, I hit the bulkhead, which we call a wall. Nothing happened to me. I got up and of course, my bunk was close to the catacombs (?) to go down to the number one engine room. My battle station was number one throttle for the number one shaft. When I went down there, it was all white smoke. You couldn't hardly see anything. When I went down there, I saw enough to see where I was going. Everybody complained about the smoke in other interviews about the torpedoing. Finally, the ship was listing and it finally was righted to an even keel. They flooded the magazines opposite from where the ship was hit. Then that was it. About six minutes later we got out first chase of speed. To pick up speed to get out of the area. That was the torpedoing

incident. Of course, everybody knows where they were and they will have another version. But I was on the same level where that torpedo hit. The boy that was killed in the washroom--Pone-- me and him did boot camp together.

[Interviewer]:

So you had been with him since the very beginning?

Leo K. Neumann:

Yes. He was in that washroom and he was killed. The other four men were in a compartment and when they took their bodies out all their hair was burned off. One man on topside was blown overboard. Never found. That was only a small horror of war. There are plenty of horrible stories that go on.

[Interviewer]:

When you went to your battle station, what was your job to do?

Leo K. Neumann:

I was a throttle man. I was in charge of the steam to be admitted to the turbines from the boiler. In other words, I get to change the speed, I answer the bridge. I will turn the enunciator and they will send me down say from 77 turns to 120. I will acknowledge that I received a message and I will open the throttle slowly, checking my steam pressure that hasn't dropped too far until I feel the turns went from 77 up to 120.

[Interviewer]:

You said you were an old salt by that point. How long did you actually spend on the battleship? How much time?

Leo K. Neumann:

I say an old salt in a little jokey way because at a year and half you're not an old salt. I was an old salt as compared in mess cooking duty. That was supposed to have been done within the first year of duty, but like I mentioned, they over looked me somehow and I was an old salt of year and a half to do that. I spent from 1941 through 1944 which included all the action, I guess twenty-five months overseas. The first twenty five months, two years and one month overseas before we were allowed to go back to Bremerton, Washington, for an overhaul. That is when I left the ship and I went to another ship.

[Interviewer]:

What ship was that?

Leo K. Neumann:

The USS NEWBURY. An APA, marine transfer ship. My next duties on the APA was I took the marines to Iwo Jima and that is where I saw the real horrors of war because we were close and what we would do on an APA . . . These Higgins boats would bring back the wounded and we would take care of the wounded and we do what we could for them. That is a horrible sight to describe. All the marines were nothing but young boys like I was and their only worry was they were screaming for their mothers. That is the saddest part you can think about. The boys were bleeding and hurt.

[Interviewer]:

Of the twenty-five months that you spent on the NORTH CAROLINA, what were some of the things that you liked about it? What are some things that you recall fondly? Then what are some things that you didn't particularly like about it?

Leo K. Neumann:

The fondest part of it was the camaraderie that we had amongst our men. We had the proper training because of the war, the way it broke out and the time the ship was built and the time after the war broke out on December 7 that we still had training enough and the confidence amongst the crew to repel air attacks and to take care of any situation that would arise. We were confident that we could do anything that we wanted to do. The heat, of course, was the Pacific and the beautiful islands which are not as beautiful as you think they are. It was uncomfortable, it was very rash. You couldn't get excited too much, because you could get yourself into an awful lot of trouble. Of course, the officers didn't like you gambling and things like that. They didn't want you to go ahead and make any unnecessary noise, which they thought was unnecessary. They were pretty strict. In fact, I can tell you an incident that I have in the log. You weren't supposed to have any cameras, no pictures. It was very secretive.

[Interviewer]:

Because of security?

Leo K. Neumann:

Security and whatnot. Don't you think one of the sailors, they found he had a camera, the next port he was taken off the ship and handed over to the FBI. The strictness of it all. It was their routine; it was their procedure. We all had our clothes stenciled. Underwear and shorts are all stenciled with your name. If you were caught with somebody else's clothing, they would nail you for that and give you some sort of deck court-martial or they would give you some extra duties and things like that. It was very strict.

[Interviewer]:

I was just trying to think if there was anything we hadn't touched on. I guess in the twenty-five months that you spent there, I am sure you spent holidays aboard ship or either at liberty port. How did the crew come together for holidays or special occasions?

Leo K. Neumann:

All that time, there was Christmas, New Year's, Thanksgiving and everything else, we would try to have a vacation. Relax a little bit and have a decent meal. The Captain was enough to say that, because a lot of the stuff was very rash stuff, hard stuff. Not too appetizing. It was appetizing enough. Like when Christmas would come, we would have our Christmas services for church. We would have a nice big meal and then, of course, we would try to get mail. Mail was a big thing. The mail was always coming from destroyers that would come along side. They went to a port and they picked up our mail and they would come out and give us our mail. This happened with a lot of the capital ships that were not able to come to port too often. We didn't come to port that often, you know. We were more or less at sea quite a lot of time. I think it was twenty three thousand miles within forty days that we traveled in the South Pacific. That is a lot of traveling for a ship of that type anyway. I am finding out more today through the Navy archives, through the log and through the action reports what our missions were. Of course, you know, the USS NORTH CAROLINA is a battleship. I found reports that we were secret enough that they put down that we were operating as a cruiser, which is the next class from a battleship

which is a smaller ship than a battleship. After cruisers then came the destroyers which were know as tin cans, tin can sailor destroyers. Battleship was not included. We were operating with the ENTERPRISE as a cruiser. It was pretty secretive to say that we were there and they didn't want to know that we were there in that area.

[Interviewer]:

So in the times you spent there, you tried to make the best of all occasions?

Leo K. Neumann:

Yes. It is pretty hard to remember all these things. How you entertained yourself. There wasn't much entertainment especially at sea. Of course, when you are engaging the enemy you are at general quarters ten hours, twelve hours, maybe all day and all night. Then you will have a snooper coming around at night just to annoy you. A plane would come, they called snoopers. You had to stay at GQ. You didn't know what they were going to do. Later on we got used to that. Washing Machine Charlie was going to come around and okay we will see what he is going to do now. But I can remember on one occasion in the Gilberts--this is night action now. This is ten or twelve midnight, one, two in the morning when Jap planes would come down. We had ten different separate attacks from Japanese planes. It was on November 26, 1943, that Frank Butch O' Hare was shot down. Frank Butch O'Hare was the Navy Ace. This is why O'Hare Air Field in Chicago is named after this man. The ship was there at the time that he was shot down. That is a little interesting note, because the connection that you can have with different things. These things I learned now after the war because you weren't told all this. This was all secretive stuff. Everything was top secret and it wasn't declassified. Finally all these things are being declassified. You have got to go get it. It ain't coming to you. You have got to go out and get it. I found this all out. I do this because I have a sister in Maryland, not too far away from Washington, DC. I go to the Archives. That is my opportunity. I guess nobody else would do it. That is the opportunity for me to go there and I take that opportunity.

[Interviewer]:

That is wonderful.

Leo K. Neumann:

I gave Kim, you know Kim (a curator), I have gave her several pieces of artifacts. I gave her some new stuff today that I am sure she is going to find interesting. She has got to take time, I gave her an awful lot of stuff. I think she is a little confused. I must have confused her. But she is doing fine. She will sort it out.

[Interviewer]:

That is terrific. The last thing I want to touch on is all of these people coming from all over the U.S. to serve on the ship. Including some black sailors as well and people from all different types of cultures. What were the relationships of those different people?

Leo K. Neumann:

The people from the South do have their own way. We used to call them “barefoot country boys.” They would act like they would know more the anatomy of a frog than they would know of a woman, I think. But they knew all these things about shooting guns, which people from cities didn't. The blacks were strictly officers' mess men. They were assigned general quarters. They did have a twenty millimeter mount to mount for air attack against enemy planes. They were strictly mess cook--attendants for officers. They weren't in any other division at that time. It was more or less segregated to a large degree. It was just that way. There was no way that you could even face it. We would go with them and everything else, but then even going you had your laughs and you had your fun with them and everything else but when you wound up, you went your way and he went his way. It was just that way. Not that it was forced on us, but it was on us anyway. It was there. Not to say that there was any dislike. There was no dislike whatsoever.

[Interviewer]:

It was the times.

Leo K. Neumann:

It was the times and everything else. It was an atmosphere that you couldn't control. You did what you could do. You had laughs, you had fun. You exchanged things. In fact, to

one black fellow I had said, “We are going to meet in Jack Dempsey's fifteen years from now.” Jack Dempsey's was a big place in Broadway, New York. I said, “This guy ain't going to come.” So fifteen years, I went there. I sat there and I sat there. I saw this black guy with a boy. I didn't recognize him, but I recognized the boy. He was fourteen or fifteen years old. I recognized the boy, but I didn't recognize the guy I knew.

[Interviewer]:

He looked like his father.

Leo K. Neumann:

I said, “Hey Ashford, is that you?” He said, “You Leo?” I said, “Yes.” We had a good time together. The boy I recognized because he looked just like him when he was young.

[Interviewer]:

That is a beautiful story.

Leo K. Neumann:

It was fantastic. So we had a little fun that day.

[Interviewer]:

That is wonderful. Mr. Neumann, is there anything that you would like to add, any special memories or any special statement about your time on the battleship?

Leo K. Neumann:

Well, the battleship itself received an awful lot of publicity at the time. It was on the front page of the New York papers which was the Daily Mirror, the Daily News, the New York Times at the commissioning. It was glorified quite a bit to a point where it was called the “Showboat.” There was a favorite play on New York at the time called the “Showboat,” which was where they got the nickname, because we were going in and out of the harbor so much in New York, “Here comes the Showboat again.” Of course, out sister ship the WASHINGTON, the BV-56, they were doing the exact same thing we were, they were just as good as anyone else aboard that ship was, but they didn't get the recognition that the CAROLINA was getting. That kind of peeved them. “Showboat! Showboat!” It stuck, the name stuck.

Today, these reunions we are having today are most fantastic, especially the fiftieth we had aboard on April 9, 1991. That was an awful lot of men came. That was an organized chaos, but it was fun.

[Interviewer]:

How did it make you feel being on the “Showboat? “ Was there a lot of pride that went along with it?

Leo K. Neumann:

Well, not knowing what our missions were and the details of them, we appreciate it more now, because we know what the mission was. All the secrets are out. We know what we were doing there. We know why we were there, why we left Guadalcanal that night of August 7 to go south. Then the debacle at Sabo Island the next night of the three American cruisers sunk, the VINCENNES, the QUINCY, and the ASTORIA was sunk by the Japanese. And why we weren't there. We got the answers now. We know why we went south and left them cruisers there by themselves. It was secret. We wasn't supposed to be there. That is what we say today. But there is a lot of other things that we find out today why the ship did this and why we didn't do that and why was it necessary that we didn't do it. I find it very interesting today. I know more about the ship today than all the time I spent aboard it.

[Interviewer]:

That is wonderful. I want to thank you for your time, this was a wonderful interview.

Leo K. Neumann:

I wish I could think of more. There is a lot more, but you will have to search me.

[Interviewer]:

I think you touched on everything marvelously. Thank you.

[End of Interview]