| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| Capt. Earl A. Luehman | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| June 6. 1991 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you born?

Earl A. Luehman:

I was born January, 1918, in Milwaukee. My father was a police captain and my mother was a housewife. In high school, I played a little football and I was on the swimming team.

My brother, who is seven years older than I am, went to New York to attend a private prep school for six months. He had an appointment to both Annapolis and West Point. In those days they couldn't give them away. He passed the entrance exam, which qualified him for both academies. He took the physical at Annapolis and "bilged" out on his teeth, so he went to West Point instead. He graduated in 1934.

Being seven years younger, I had to emulate my older brother, so I went to the same prep school; however, I wasn't able to get an appointment. Three years out of high school, I managed to get a third alternate, but that didn't give me much hope. I did take the examination, at the old post office in New York, and passed it. The prep school was run by

a chap by the name of Benny Leonard. He was an odd character, very eccentric, but delightful. He had me fill out a questionnaire concerning my background, what I had done in high school, that sort of thing. When I arrived back home in Milwaukee, I learned that the principal appointee had passed the exam. I got a job in a bakery working nights. Then I received a telegram from Rip Miller, the football coach at the Naval Academy. He said, "Congratulations, you passed the exam. If you really want to get in, meet me in Washington. We will see if you can get an appointment."

I quit my job and went to Washington. He and I stalked the halls. I got my Wisconsin congressman to trade off his next year's appointment to one from Kansas. So, I actually was appointed from Kansas.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you really given that much thought to a naval career?

Earl A. Luehman:

Everything I can remember pointed me in that direction. I came from an authoritative background. My dad was a police captain. My brother went into the military. I really had no other objective. Going to the academy was the toughest thing I ever experienced. I had been out of high school for three years and my study habits had disappeared. Most of the people entering the academy had a year or more of prep school or a year of college. So I was at a tremendous academic disadvantage. I struggled for all three and a half years.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well the method of instruction there at the academy was different from what you had experienced previously, wasn't it?

Earl A. Luehman:

That's true, but I had to learn to study. The subject matter wasn't that difficult. It was more a matter of trying to keep up with the rest of them who could breeze through. I had a pretty tough time for three and a half years. The happiest day of those years was when

they said we were graduating early.

Donald R. Lennon:

You did play football at the academy, didn't you?

Earl A. Luehman:

No. I swam for the team, but I didn't play football because I couldn't afford the time. I just couldn't take the time away from academics. I was just barely getting by, working like hell.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have a recollection of any special events or incidents having to do with the social life?

Earl A. Luehman:

No, I haven't. I had been dating my present wife since she was twelve years old. She made it to every June Week we had. That was my only social life. What can you do on two dollars a month? I earned two bucks the first year, five dollars the second year, seven dollars the third year, and ten dollars a month during our first class year. You can't do much on that sort of thing. I can't recall much social life.

Donald R. Lennon:

Having been out of high school for three years when you started, you were a little more mature than some of the other students. What about the prankish activities you sometimes ran into?

Earl A. Luehman:

Well, I wasn't the oldest one in the class. The hazing was rough. Every time one of the upperclassmen would come in we had to do our class number of pushups. I guess I did forty-one pushups at least three times a day for the first year. It wasn't that bad. I got paddled a few times. I put up with it because it is part of the training. Our class started out with over 500, but we only graduated 399. It was a pretty select group.

My first assignment was on a light cruiser, HELENA CL-50, at Pearl Harbor. This was in March. I reported aboard, with another classmate. There were two openings. One of us was to report to engineering and the other to the deck. I lost and went to engineering, but that was fortunate for me, because I qualified as an engineering watch officer underway

within four or five months. Then I was promoted to the deck force. Being in the deck force second division, I was the after high turret captain. The HELENA had five 6-inch gun turrets (triple) and four twin 5-inch 38-caliber. I had the after high turret, three 6-inch guns. Of course, then Pearl Harbor came along. I had the four-to-eight watch the night before. We had all been expecting something to happen but didn't know when it would.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was the HELENA berthed?

Earl A. Luehman:

We were at 10-10 dock, which was the berth of the flagship of the Pacific Fleet, the USS PENNSYLVANIA. The PENNSYLVANIA had gone into the dry-dock ahead of us, and we had moved from our buoy position to her position, to fix an anchor engine. When the Japanese attacked the next morning, their maps showed the PENNSYLVANIA in our position; consequently, we caught the first torpedo. Alongside of us was a wooden mine sweeper, the OGLALA. The torpedo went under the OGLALA, blew a hole in our after engine room, killing about sixteen, and tore the bottom out of the OGLALA. She had to be towed in back of us, where she rolled over and sank. That was the extent of our damage during the attack.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were saying, you were on watch.

Earl A. Luehman:

No, I was mistaken. After checking my notes I found that I had stayed aboard the night before. My classmate, Bill Jones, had the 4:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. Just before he was relieved, five minutes until 8:00, the attack came. He did a marvelous job. He never panicked. "General Quarters, this is not a drill."

Donald R. Lennon:

You were in the sack at the time, weren't you?

Earl A. Luehman:

No. I was just getting dressed for breakfast. I was just putting on my whites when the torpedo hit and knocked me flat on my butt. I didn't know what had happened. The

general alarm went off and we all dashed back to our battle stations. There wasn't much I could do on my main turret. All I could do was watch with my periscope. The 5-inch guns were firing. We got credit for shooting down at least one Zero. That was a spectacular sight. There was a tremendous smokestack on the dock, about an eighth of a mile from our dock. A five-inch-gun went through the center of that stack, about two thirds of the way up, and hit a Zero. That is the one that we got. I don't know how long they left the hole in the stack or when they fixed it.

They patched us temporarily and we escorted a transport of Navy nurses back to Hunter's Point. We stayed there from December until about February.

While we were in drydock, we got one of the few installations of the new fire-control radar. We got out just after the tremendous defeat at Guadalcanal, when the QUINCY, VINCENNES, and the ASTORIA were sunk by the Japs. The aircraft carriers were deployed somewhere else. Practically the entire U.S. fleet in the Pacific was sent down to try to stop the Japs--to reinforce Guadalcanal. We were part of that Fleet. We got down there and engaged in four night battles--battles I will never forget.

The Japanese would reinforce at night, escorting the transports with battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. Our task force would stay in during the day and leave at dusk. As the coast watchers reported the Japs coming down, we would steam back in. The first night battle, we picked the Japs up on our radar. We were in a column. When the automatic control took over, the guns were at maximum elevation. The range was about 17,000 yards. The turret officer's position is directly behind the middle gun. I could see the guns get lower, lower, and lower, until they were practically horizontal. Word came through: "Commence firing." This was all automatically controlled by a central command. Fifteen

6-inch-guns took off. Looking through the periscope, the tracers from fifteen guns looked like a swarm of bees heading for a target you couldn't see. Suddenly, they disappeared, and within a half a second there was an explosion. We had hit a cruiser and sunk it. Then we shifted targets, and then the battle started. We didn't get a scratch. We stopped them from unloading and reinforcing the Jap forces on the island that night.

Donald R. Lennon:

They didn't know you were there until you hit the cruiser!

Earl A. Luehman:

During one of the four night battles, we were shooting and there was a lull in the firing. Three guns were loaded. We were on automatic control, meaning I had no button to press, they were pressing them in command forward. All of a sudden, we started firing. As they were loading the second round, there was a terrific explosion. We got hit directly in the faceplate of the turret, which was six inches of casehardened steel. You couldn't draw the center any closer. It blew the leather protector off of the center gun. It had scarred the bronze chase of the gun so that it could not retract. The guns were loaded again, which meant there was a live round in this center gun, but I couldn't fire it. We had to eject it. In ejecting the gun, the ammunition hit the deck. All the powder spewed over and started a fire. People had to come up on deck to put out the fire.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you know what they hit you with?

Earl A. Luehman:

They said it was a 5- or 6- inch shell. They couldn't be certain.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was 13 November.

Earl A. Luehman:

Yes. The third battle of Savo Island.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have much feeling for how much damage you were doing in these night battles?

Earl A. Luehman:

Yes. We knew ships were being sunk, because they disappeared off the radar. I

didn't keep track of numbers for any of the individual battles. We were milling around so close, in such confusion, that the battleship HARUNA, with 14-inch-guns, couldn't lower her main battery low enough to hit us. When she fired her main battery it went right through our rigging, above the bridge. It sounded like a freight train going over the ship. It scared the hell out of me!

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they have subs in the area?

Earl A. Luehman:

No. There were too many torpedoes flying around. The Japs brought down a lot of destroyers with torpedoes, and I think they were afraid they would lose their subs to some of these.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, they were dropping torpedoes from the destroyers.

Earl A. Luehman:

They were accurate and there were no duds when they hit. I had qualified as officer of deck underway before December 7. During the last night battle, the SAN FRANCISCO had taken a terrific beating. The admirals aboard the SAN FRANCISCO had taken a direct salvo on the bridge that just wiped it out. It was Sunday morning. There was a clear cloudless sky, blue as blue could be. The water was like a mirror. We were steaming south, out of the area. We were the flagship now. The SAN FRANCISCO was off on our port quarter and the JUNEAU was off on our starboard quarter. She was down eight feet by the bow, because she had taken a torpedo hit. All of our destroyers had used their depth charges the night before; so, they were useless against any sub attack. I remember looking through my binoculars at the SAN FRANCISCO and seeing naked bodies being dumped over the side. There wasn't time to wrap them up. They would tie a five-inch shell to their leg and dump the body over the side. There were dozens of bodies. They would put them on a slab, say a prayer, and slide them over the side. While this was going on, we were

zigzagging. The lookout called down from the crows-nest, "Torpedo, port bow." I looked and sure enough two streaks of bubbles were headed directly below my feet. I stood up on my tippy toes, because I knew if they hit they could break my leg.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't have time to maneuver?

Earl A. Luehman:

No, we couldn't do anything. They were within a hundred yards. The torpedo passed right under us, without ever touching. The next thing I knew, the JUNEAU had completely disappeared. Her five-inch-mount blew over our ship and she just disappeared in a cloud of smoke. There wasn't anything left to see--no debris, nothing. We were left with the SAN FRANCISCO, destroyers without depth charges, and a submarine that was out there waiting to kill us.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there any survivors from the JUNEAU in the water?

Earl A. Luehman:

If we had gone back to look for them, the sub would have gotten the SAN FRANCISCO and us. In any case, how could anyone survive a total destruction of a ship in less than three seconds?

There was an army B-17 overhead. I signaled and sent them a message, "JUNEAU torpedoed. Possible survivors in the water." I got an answer, acknowledging they received my message. They never reported anything. Going full steam, we got out of there as fast as we could. During an interview, later on, the Japanese skipper of the sub said his intention was exactly what happened. He shot under us to get the JUNEAU, because he knew it was down by the bow. He could see the damn thing down. The torpedo hit their depth charge magazine. He was going to hit us next. By going full speed ahead, we got out of there in time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the SAN FRANCISCO, in it's condition, able to move out fast enough?

Earl A. Luehman:

She had full power. In other words, the engine rooms weren't damaged a bit, just the super structure.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were just beat up.

Earl A. Luehman:

She, the HELENA, and two destroyers hauled ass out of there.

This brings to mind another incident that occurred one afternoon in the bay off of Guadalcanal. We got word that a flight of Japanese Bettys, twin engine bombers, was coming down. They came over the horizon, right above the water. They didn't attack us. They were trying to hit our transports. We shot them all down, but I remember seeing this one come in. He was no more that fifty feet away when he dropped his torpedo. He was going too fast, however, and the torpedo hit, bounced, and flew right over the destroyer. It is something that you just can't even picture. He must have been scared as hell. He was just going too fast for the torpedo to take hold. When it hit, it hit at the wrong angle and skipped like a rock on the water. It went right over that damned destroyer--amidships. I was sitting in the turret watching it through my periscope.

Four night battles had left me a little shaken. I said, "That is just about it. Let me go to flight training." I put in for flight training and fortunately got it. I left in December to come back to the States and in April, the HELENA was sunk up in Vella Lavella.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there a heavy loss of life among the men you had served with?

Earl A. Luehman:

The torpedo blew the whole bow off; they lost about forty or fifty men in the forward section. It took the number one turret and the whole bow of the ship off. The second torpedo hit amidships and broke the back. They didn't lose too many in the actual torpedo hit. They lost most of them in the rescue operation. The destroyer that had stopped to pick them up, suddenly got word that the Japanese fleet was coming back. There were

survivors around the destroyers, trying to be hauled aboard. The destroyers took off at full speed and just drove right through these guys. The chief engineer, Elmer Buerkle, was cut to pieces by the destroyer prop. We lost a lot of people that way.

I went to Dallas, went through primary, and then went on to Pensacola, where I got my wings in September of 1943. I stayed around Jacksonville for about three months as an instructor in seaplanes. I transferred over to land-based four-engine bombers and transitioned in the Navy Liberator. That is the Navy version of the old B-24 only with a single tail.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't know the Navy had much in the way of bombers like that.

Earl A. Luehman:

Yes. The Fleet would take an island, like Eniwetok, Tinian, or Guam and as soon as they had control of the Jap airstrip, we would come in and fly patrols to protect the invasion force from any approaching fleets, submarines, and whatever and keep them from sinking our transports. We were probably the first land-based airplanes to come in. In Okinawa, I remember I landed before they had even taken half the island. The Liberator had a crew of twelve. It carried nine 500-pound bombs and twelve 50-caliber machine guns in six twin turrets. It was a pretty effective fighting machine.

Donald R. Lennon:

It wasn't too cumbersome to use against ships?

Earl A. Luehman:

No, it was very maneuverable. The old B-24, with the twin-tail, was a very sluggish airplane; but with a single-tail, it was much more maneuverable. We would fly it at very low altitudes, search for six-thousand, eight-thousand-, and nine-thousand-ton cargo/tankers, pickle off one or two bombs, and there she went.

We transitioned in Crows Landing, California. On our first deployment, we went out to Honolulu, Kaneohe Bay. From there we went to our first operation, I think it was

Eniwetok.

Some of the experiences with this squadron were unbelievable. When they went into Okinawa, we took over the Japanese airstrip, which was made out of dead coral. Usually, they were not long enough for a large airplane to take off. They would try to extend it with more coral, as best they could. We would immediately start flying patrols off those old airstrips. I remember one time, at the end of one of these airstrips, there was something that looked like an old oak tree. I had a full crew and a full load of nine 500-pound bombs. It had rained for days, and that dead coral didn't drain away that well. My wingman and I always took off as close together as possible. My wingman took off first. We taxied out and the wheels sunk in, almost up to the middle of the wheel. I added power and we started to roll, but we just couldn't get any airspeed, due to the soggy, wet runway. We had passed the point where we just couldn't stop anymore; I pulled that son-of-a-bitch off the ground and glanced off the top of the tree. Branches were scattered all over the place. Fortunately, the hill sloped away, down towards the bay. The plane was handling absolutely mushy. I nosed it over the best I could and gained enough air speed going down the hill, that I roared out over our Fleet. This was about the time of the kamikaze attacks. It scared the living beJesus out of them.

Donald R. Lennon:

None of them tried to take a shot at you, did they?

Earl A. Luehman:

No. It happened so damn fast. I came back and there were branches of the tree still in the wheel wells. They sent the fire trucks and everything else out, thinking I was going to crash.

During one patrol, just before they invaded Iwo Jima, my wingman had some mechanical trouble and couldn't take off. I was flying up and got about five miles west of

Iwo Jima at about 8,000 feet. I figured I had better get a little altitude, so I added power. The airplane was climbing in a level altitude. Suddenly, my forward gunner yells, "Zero, dead ahead." Sure enough, I looked up and about 2,000 feet above us is a Zero diving in on us. This guy dropped an air-to-air phosphorus bomb that exploded about fifty feet below us. We flew through the streamers of this thing. If the phosphorus bomb had hit us, the plane would have disintegrated. As he passed us, we turned into him and I had twelve guns on that son-of-a-bitch. He went away burning. I figured they would send somebody else up after me now, so I headed back. Sure enough, there was a brand new, what they called a "Jack," a new development after the Zero. I looked at that guy and I could see his wings blinking. He was firing everything he had at me. He never hit us. I pulled under the clouds and headed back to the base. I wasn't about to tempt fate anymore. We got away with that one.

Another time we were on patrol up towards Tokyo Bay. We passed over a small island and there was a Japanese sub. Our instructions were: Never drop on a sub, because it might be one of ours, but send back information about where it is and get permission. We followed the instructions and, of course, it took forever. We finished our patrol up to Tokyo Bay and back and never heard a word. We landed and finally got a word to drop on them. So we took off again and we dropped four 500-pound bombs.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you had no trouble finding it?

Earl A. Luehman:

Oh, no. He was hiding in an island. I think he was damaged. The conning tower was above water. He was in very shallow water, in a little cove. Four 500-pound bombs from one quarter, two of them hitting, one hitting forward of the rear quarter, and the other right on the forward quarter. We couldn't help but sink that son-of-a-bitch. We got back

and reported in. All of a sudden, I got a call to go on the flagship. Some stupid jackass called me in, "So you think you got a sub, do you?"

I said, "Yes, sir."

"How do you know?"

I said, "Well, we've got pictures of the bombs straddling it. We couldn't have missed. We blew it up; we saw it disappear."

"What kind of oil was it?"

"What do you mean what kind of oil was it?"

"Well, couldn't you smell? Was it diesel oil?" This jackass wanted me to stick my nose out the window to see if there was diesel oil coming from the submarine.

Donald R. Lennon:

You couldn't have smelled it.

Earl A. Luehman:

I know. I know. This was some idiot, who was running seaplanes out there and not knowing what he is talking about. Well, we didn't get credit for that submarine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Because you couldn't smell the oil?

Earl A. Luehman:

Because I couldn't smell the oil. During the entire war, our squadron got credit for nine 9,000-ton ships and six 5-6,000-ton ships. We got enough of them. Another squadron, same type of planes, lost one of theirs. He went over one of those small freighters and dropped on it. It happened to be an ammunition ship. It blew up right under him, blew him out of the sky. So, we were very leery about how we dropped those things.

The Japanese hid in the coves during the day and came out at night. There was one strait between Pusan and an island south of Pusan that they used as their exit points. We wanted to mine that strait. Two of us went up, Art Farwell and myself. We had a 2,000-pound mine. A 2,000-pound mine is a pretty heavy piece of luggage. These mines were

armed so that they would let one or two ships pass by and then go off. They were set for decoy. So they wouldn't see us coming, we flew up almost on the water--so low, the props were kicking up spray. When we got to the land sighting, where we were going to turn in and drop, we got into formation and dropped them exactly where we should have. Two 2,000-pound mines hit the water and the plane, of course, rose about five hundred feet. As I turned between those two islands there was a Japanese cruiser sitting down there, and little white uniforms were running like hell all over the deck. They couldn't get manned before we got away. If they had seen us coming they would have caught us "dead cold" coming around the corner. We'd fly so low and so close to shore installations, taking A-A fire at two thousand feet, that we'd think they couldn't miss us. We were lucky. We stayed out there until the end of VJ Day.

[Was your Distinguished Flying Cross for any particular engagement?] That was for the twenty-five combat patrols in Tokyo Bay.

Donald R. Lennon:

And your air medal, too?

Earl A. Luehman:

Two air medals, and I've got eight battle stars. The ship, HELENA, got a Navy unit citation and a Navy commendation.

Subsequently, I went through electronics school and then went out with a squadron, first as exec and then as skipper of the Airborne Early Warning Squadron VW-1. We started out flying B-17's, with the large radome underneath. We were supposed to go forward of the Fleet and, by radar, advise them of any incoming enemy aircraft and direct fighters to intercept. It didn't work out very well, because the B-17 wasn't a good platform and we had no height-finder. Then we got the Constellation. It had the height-finder on top, radar that gave the height of the aircraft, plus a very improved search radar below.

Those worked very well. We also had highly improved communications gear, so we could get out 300 or 400 miles ahead of the Fleet and cover them. We ran numerous exercises with the Fleet just to prove the point.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is probably in the early 1950s. When was your period as Naval Attache in Soviet Union?

Earl A. Luehman:

Well, there are a lot of things in between that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Okay, I didn't mean to get out of sequence.

Earl A. Luehman:

I taught navigation at Iowa State College for two years before I went to Airborne Early Warning Squadron 1. Then I was Navy operations officer for Task Force 8, which was the atomic test series at Eniwetok. I went through about twenty atomic tests. We would coordinate the logistics of supplying the food and the rest of the stuff that the task force needed. In addition, we had a squadron of P2V's, which I would send out in search pattern to cover the downwind area from a shot, to clear the area before we could fire. It was quite a complicated job to coordinate everything. Afterwards, I went down to Trinidad as commanding officer of the Naval Station. In 1962, I went back to Russian language school. From 1963 to 1965, I was the Naval Attache to Moscow.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is there anything in particular that happened either in Trinidad or in Moscow?

Earl A. Luehman:

I was in Trinidad before the independence of Trinidad and Tobago. It was still a British colony. We had gotten the base in a destroyer-for-bases deal, where we gave them destroyers and they gave us bases on their property. The Gulf of Paria is a tremendous gulf, protected by a very narrow entrance, and it's where all the convoys assembled for the South Atlantic run during WWII. It was a staging point for the resupply of the B-17's to Europe. After the war they wanted to keep this as a functioning base, in case of another outbreak. It

remained there and the facilities were maintained.

The Governor General of Trinidad and Tobago was a Lord Hailes [Patrick George]. He had been a leader of the British conservative party in Britain. This was just after the time the British and the French had started the Suez campaign and Eisenhower had said, "Get out or else." As a consequence, Hailes' party lost the premiership--lost the election--and he was demoted to Governor General of Trinidad and Tobago. You can imagine the reception I got as senior officer coming down. I went down because we had an unsatisfactory relationship with the premier, Prime Minister Eric Williams, a very intelligent black man who was educated at Howard University. He married an American black woman and later divorced her. He failed to keep up with his alimony and because of this, he was not permitted to come back to the States or he would have been arrested. So, he didn't have a very good opinion of the United States.

The skipper who was down there was not very much of a diplomat. He would get drunk and make silly statements about how he could teach these people where to go. They relieved him and I got the job. It took a little doing, but when I left, Williams and I were pretty good friends. Lord Hailes threw me a beach party. He and his wife, and Helen and I went down as the only people on the whole beach. We got along very well.

From there, I went to Russian language school and then to Moscow. These were the times before they had the satellites. The only intelligence you got was by eyeball. So it was a very, very interesting period.

We weren't allowed to drive ourselves in Russia, because it could get us in trouble. We were assigned drivers. My driver was a full colonel in the KGB. He didn't tell me that, but we knew that he was. They used to practice for their May Day parade, late at night.

They cordoned off all the streets and ran tanks, machines, missiles, and everything. I was at a diplomatic function somewhere on the other side of town. We were coming back and there was a bunch of missiles going by. The cops stopped the car and wouldn't let it go. My driver got out and said two words to the guy in charge. He stopped the damn parade and allowed us to cross. We knew damn well that we couldn't get in trouble because we always had someone following us. It was so funny.

When I went to Russia, the fellow I relieved was a classmate of mine, "Jay" [James Houghton]. We met in Leningrad. We were standing on the key waiting for a boat to take us up the river to a place called Petrodvorets, Peter's Palace, because on the way there was a shipyard where they made small, fast missile boats called Komars. They were very effective at that time. We wanted to see how many they were building and we wanted to take a look.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you used the excuse of going to Peter's Palace?

Earl A. Luehman:

Sure. While we were waiting on the dock for this boat to come, Jay poked me and said, "Look over your left shoulder." There was this idiot, holding a briefcase that had a square hole cut in it.

He was pointing the briefcase at us, taking pictures. There was a camera in that damn briefcase. He was trying to look so innocent. We got to Petrodvorets and all of a sudden, the sky opens up. It started raining something terrible.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now are you driving yourself at that time or did you have the driver?

Earl A. Luehman:

No. We didn't have a car. We had taken the boat up there. We got off at the landing at Petrodvorets. We had to walk about a quarter of a mile to get behind the parking lot where there might be a taxi. By the time we got there, however, all the Russians had

taken the taxis and they were gone. Jay and I were soaking wet. We asked a Russian where the train station was, so that we could get back to Leningrad. He showed us the way. Fortunately, it stopped raining, and we started to walk on back. All of a sudden, a taxi cab came roaring around the corner, stopped in front of us, and the door was opened for us. We got in and were taken back to the hotel in Leningrad. We were never asked where we wished to go!

Donald R. Lennon:

What was supposed to have been your main function in the Soviet Union as Naval Attache?

Earl A. Luehman:

Basically, it's intelligence. I had to find out what they were building and what else they were doing. I had to see whether or not they were building a new ship design. We went to Leningrad about once every two weeks, because they were building subs in the Neva River. We could walk along the other side and see what they were finishing. If it was anything new, we could report it. We tried to take pictures. This was our only means of intelligence.

Donald R. Lennon:

I mean, you were supposed to have been there for protocol purposes. Of course, everyone knew why you were really there. How did you get the KGB driver?

Earl A. Luehman:

This is a point of interest. At that time, I lived in the embassy in an apartment on the sixth floor. If I needed a maid, a driver, or anything like that, I would go through "Oupaydcah" (A Russian agency to assist diplomats), the official foreign office organization that supplied foreign diplomats with theater tickets, maid service, and that sort of thing. I fired my predecessor's maid. I got a replacement within a day or two. Had I not been senior Naval Attache, as my friends found out when they fired their maids, it would have taken weeks for a replacement. The Russians, however, had to have someone in my house to see

what was happening.

We would play games with them. The maids knew that they were

required to provide certain correspondence, mail, or whatever. We would leave things laying around for them, innocuous stuff. We got to know Anya, our last maid, so well, that any time we wanted to talk about something she didn't want to report back, she would motion to us to get away from the telephone or to get in the corner where there were no bugs.

While we were there, they found seven bugs in my apartment. They found a cable running along the rain gutter to the adjoining apartment building. They traced the cable back by feeding a signal into it, which would cause a loud hum at the location of the microphones. They were so sensitive that you could hear a whisper at forty feet. They were placed so that we could never find them. For example, they had them built in like a hollow piece of macaroni, behind a radiator, so they wouldn't get painted over.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they installed when the building was constructed?

Earl A. Luehman:

Either that or during modification or maintenance, because our maintenance was done by Russians. It was an interesting game.

My assistant went down with the Air Force assistant to a place near Yalta, in the southern Soviet Union. While they were there at dinner, they decided to try to get a daylight flight back. You see, the Russians always put us on night flights so we couldn't see anything. Well, for some unknown reason, they got a daylight flight. Somebody made a mistake. It must have been caught later on by someone else, because when they went to bed that night, they became deathly sick. The next morning they couldn't be waked up, so they missed their daylight flight. They were able to catch the next NIGHT flight back. When

they got back, we immediately took blood and urine samples and sent the samples to Finland. The results showed they had been drugged. Finland sent back a resume of what type of drug it was and how much they had been given.

Someone drugged them so they couldn't get the daylight flight. I confronted my contact in the foreign office; I raised hell with him. He said, "No, Oh, your men just drank too much. They found wine bottles in the waste basket." I told him what the laboratory had reported. He said, "Oh no, that couldn't be right."

Another time, our people were trying to drive somewhere and there was something going on that they didn't want them to see. They were about a mile from the embassy and a truck of army recruits came barreling down the street. They blocked the road. All of these soldiers got out and started working on the street. Our people couldn't go any further. I called this guy up again and raised hell. He said, "Oh no, those soldiers were just crossing the street." I was mad. I got in my car, without my driver. I wheeled out of the embassy compound and took off down south. I hadn't gotten a half of mile and here comes a taxi with some wild man in a sports shirt waving at me, pointing me to pull over. I just kept driving right on. We were allowed, by law, to drive anywhere within forty kilometers. I just kept on driving. He tried to get me off the curb but I just kept driving. I wouldn't pay any attention to him. I got about thirty kilometers out and a motor cycle officer came up. He stopped and I pulled over. He said, "What are you doing?" I showed him my diplomatic passport.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did he speak English or were you speaking Russian?

Earl A. Luehman:

Russian. I said, "I am going out to forty kilometers. I will turn around and come back." He saluted me and he said, "Okay." He followed me. We got to the forty kilometer

mark. I turned around and came back. He saluted me and left. I headed back in and I got about halfway and there was that same idiot with the taxi cab standing in the middle of the road waving at me. I scooted around him and went back in.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was he supposed to have been?

Earl A. Luehman:

He was part of the KGB trying to stop me. He didn't know what I was going to do. They were afraid that I would contact some civilian. He must have thought I was up to something.

We were in Latvia, on an innocent visit. I wanted to see what the place looked like. My assistant and I were walking down a public square, we saw an old couple walking arm and arm. They were a nice couple; he looked like a college professor. We stopped them and asked, politely in Russian, "What is the name of this square?" He told us. We continued walking our way and they walked their way. They got about twenty feet and some little idiot, about five-foot-three, came up and grabbed them both. He started shaking them, asking what they had told us. We realized that we did not want to get anybody in trouble by talking to them.

It was so funny the way we could recognize these KGB people. One year, they produced felt hats in purple. Everybody had a purple hat on, like a fedora. The next year, they were green. Everybody had a green hat on.

Donald R. Lennon:

It doesn't sound like their operation was very sophisticated?

Earl A. Luehman:

If we would go out of the hotel, we could tell when we got back, that they had searched the place. The Russian cigarettes are called "popyrassi." They would stink to high heaven. When we would walk in our hotel room and smell all those "popyrassi," we knew someone had been in there checking our room out.

I did have a chance to fly in the commercial version of their Bear, which was an eight-engine bomber. We had the first U.S. ship visit to Russia in years. It was a destroyer, and it was sailing into a little fishing town called Nachodka. My assistant and I got permission to fly in this commercial "Bear" to a town at the head of the Amur River, Chabarovsk, which is on the border between China and Russia. From there it was about a day-and-a-half or a two-day train trip along the Amur River, down to Nachodka. We always traveled in pairs and we would take a cabin. Every time we did that, the entire train was occupied by KGB. We knew because every time we made a move, they made a move. If we would get up and walk, they would walk. It was an interesting ride, and they treated us royally when we got there. The Russian admiral came over from Vladivostok and we had a great time. It couldn't have been nicer.

The bastards, of course, always had to get the last word in. As we were leaving in our destroyer, their customs agent came aboard and I said to him, "Now, here are our passports. Do my assistant and I have to do anything?" He said, "No." He checked and stamped everyones' passports, and we got underway. It was a long trip out to the entrance of this bay in Nachodka. We got out about five minutes from the dock and a high-speed motorboat came up to us with a megaphone. They were yelling, "Stop, you have stowaways on board."

I tried to reason with this guy in Russian, "What stowaways?" They made us mill around out there for an hour and a half or more until another motor launch came up, a slower motor launch. The customs man climbed aboard. I said, "What the hell are you doing here? We don't have any stowaways on board." It turned out that my assistant and I didn't have a stamp on our passport. I broke out our passports, he stamped them, saluted,

and walked off the ship. It was just harassment, to make us madder than hell.

Meanwhile, I had sent a message back to the ship that we were being detained. It had everybody in the Pentagon alerted that something was happening. It was a little embarrassing to come back and say that the stowaways were your own two attaches.

There were ninety-some foreign missions in Moscow. As a consequence, we were going to or giving an official luncheon, cocktail party, or dinner every day and every night. It got a little boring with all this eating and drinking. I don't think the Russians had dry cleaning at the time, because everytime we went to a big reception, they would wear uniforms all spotted with gravy and food stains. Also, the women would grab the cucumbers and oranges and put them in their purses, because they were hard to come by. I had an assistant, a Marine lieutenant colonel, Jim Landrigan. He was about six-foot three and had played pro-football. There was a great, big Russian general who was about an inch taller than Jim. This guy had a great, big belly on him. We were at this cocktail party one day, and Jim and this general, who was the commandant of the Moscow District, got together in the corner, lying to each other and exchanging friendly insults. The Russian challenged Jim to a drinking contest. I have never seen two men put away as much cognac in my life. They drank water glasses full of cognac. It was unbelievable. The Russians would drink but you would never notice they were drunk. Of course, Jim passed out pretty quick.

I came back from Moscow and went to the Naval War College. I got a master's degree in foreign affairs from George Washington University. I went to the Pentagon and took the Dominican desk in the office of Secretary of Defense. This was just about the time Batista was overthrown. I spent about a year and a half there before I went to Greek school

to learn Greek. Then I went to Greece as Defense and Naval Attache. I spent three years there. I retired in 1971.

Donald R. Lennon:

The duty in Greece was not quite as interesting as that in Moscow was it?

Earl A. Luehman:

No. It was the same round of diplomatic entertaining and travel.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you, as part of your duties there in Greece, have to observe what was going on?

Earl A. Luehman:

No, not as much. We had a military assistance unit, which had a liaison with the Air Force, Navy, and Army. It had officers assigned to these units, so we knew what they were doing. There was nothing held back from us. We could go ask them anything we wanted. There weren't any secrets. It was just a very friendly exchange of ideas.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, the duty there was more what a Naval Attache is technically supposed to be doing.

Earl A. Luehman:

Yes, my responsibilities were to show the flag and represent the president. That sort of thing.

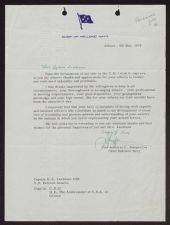

Before we went to Moscow, we had to send food because you couldn't get it over there. I had to go out and buy about $5,000 worth of canned goods and have them shipped over. If, when I had gotten over there, things had turned sour and I had been declared persona non grata, then I would have been out $5,000. To protect myself, I took out an insurance policy called P&G insurance, with Lloyds of London. It was a common practice.

Donald R. Lennon:

For your food?

Earl A. Luehman:

It would cover my losses.

Donald R. Lennon:

The embassy did not provide food? You had to provide your own food? I would have thought there would have been a government commissary type of program.

Earl A. Luehman:

Didn't have any.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not even for the embassy personnel?

Earl A. Luehman:

No. They had a small commissary, about the size of a closet. They couldn't keep anything in it. The embassy would order a train car load of produce, frozen fish, etc., from Finland. If the [political] atmosphere changed, they would let that damn car sit on the siding and rot. Consequently, we couldn't order anything. It wasn't worth it. We would all chip in to buy it and we would loose what we had put in. So we decided to take it over with us. Then, about every six or eight weeks we would go to Finland and bring back whatever additional supplies we could.

Donald R. Lennon:

They never challenged your bringing it in to sell on the black market or anything of that nature?

Earl A. Luehman:

No, not with a diplomatic passport.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned they didn't have dry cleaning for cleaning their clothes. What did you do, send it to Finland or somewhere?

Earl A. Luehman:

We must have sent it out because there weren't any dry cleaners in the embassy. We had a little snack bar in back of the embassy. That was our only entertainment. We had a little German cook that made hamburgers. We went through three demonstrations there--throwing ink against the building, things like that. They were well organized. They were brought in by the truck load. They would tell us ahead of time so we could board up the windows and that sort of thing. My children got caught in one of the demonstrations. They were at the American school, about a mile or so away, near Spasso House, where the ambassador lived. My wife had the duty that day so she rode the bus over to pick the kids up. She said she would never forget coming back and finding all these people yelling and

screaming. The kids were 8, 10, or 12 years old, and as the bus pulled in they started singing the Star Spangled Banner, on their own.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did the demonstrators react?

Earl A. Luehman:

They wouldn't hurt anybody. The demonstrators were just trying to make a fuss for the news reels and for their own internal consumption: "We'll fix those Americans." The Chinese demonstration got out of hand, however. They couldn't control it and four or five policemen were seriously injured. They finally had to bring in the troops.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the KGB follow your wife or other non-officials?

Earl A. Luehman:

No. We didn't worry too much unless we suspected that they were trying to get us "png'd" (persona non grata), or unless we had kicked somebody of theirs out of the U.S.

Donald R. Lennon:

They would be looking for someone to retaliate against.

Earl A. Luehman:

Other than that we trusted them because they wouldn't let anybody hurt us. We knew we always had somebody following us.

Anya, my maid, had a good sense of humor. I worked on the eighth floor and would come down for lunch. Of course, going to all these cocktail parties and dinners was causing me to put on some weight. I would come down for lunch and she would have bleenies and borscht--all this heavy Russian stuff. I'd say, "Look, Anya, I am not going to eat this. All I want is a sandwich and a very thin soup, that is all."

"Yes, sir." The next day I'd come down there would be chicken kiev and a great big lunch. I'd say, "I won't eat it. I told you I wanted a sandwich and thin soup." Finally, one day she looked at me with a sly grin on her face and said [in Russian], "Yes, sir. A fat rooster is never any good."

Donald R. Lennon:

What came after retirement?

Earl A. Luehman:

I retired over there and bought Helen a partnership in a Greek travel agency. We stayed over there while my son went to the Naval Academy and my daughter went to the University of New Hampshire. I worked for three years with a small electronics company that was a subsidiary of NCR. I was their marketing director for the Middle East and North Africa. My territory was from Morocco to Bangladesh. I was in the air, traveling three weeks out of every month. I have been in every damn country in that part of the world.

Donald R. Lennon:

That got kind of wearisome after a while, didn't it?

Earl A. Luehman:

You bet. I had to fly on these weird airlines. I got into Khartoum one day, and it was 120 degrees in the shade. It was just stiffling. I got off the airplane, walked through customs, and showed them my health card. He said, "I'm sorry, sir, but your cholera shot has run out." He took me over to the corner and there was a piece of canvas strung out on an old curtain rod. I walked behind the canvas with him and there, on the little counter, was a rusty tin box. He pulled out a needle and gave me a cholera shot. I didn't catch hepatitis or anything, thank God, but that is the kind of stuff I ran into. I worked there for three years. NCR sold the company to E-Systems, who gave up their efforts in the Middle East.

I sold a very high-tech, state-of-the-art communications system with VHF and UHF that was used for military communications and civil aviation. It was used in towers all over the United States. I was trying to break into a market that the British had dominated for years. I was trying to sell this as part of a major command and patrol system that Iran was developing. The Iranians finally inspected the material and agreed to use it. I got the prime contractor, which was Westinghouse, to include it in its program. The Iranians were flying to Florida to sign the contract. The next day Hoveida (the foreign minister) stopped all purchases and about a month later the shah fell. I missed out on a five-million-dollar

contract.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was time to come back home!

Earl A. Luehman:

That part of the country is so interesting. I've been all through Iran. I didn't get up north to Qom, but I did get to Esfahan and most of the other big places in Iran. I've told you about Khartoum in Sudan and Egypt. Oh, if I ever went to Israel, I couldn't get a visa in my passport. I had to have it stamped on a separate piece of paper, because if I ever wanted to get into an Arab country and I had an Israeli visa, they wouldn't let me in.

I got into Jiddah, Saudi Arabia, one night, about midnight. My contact there, a resident NCR chap, had not gotten my wire to get me a hotel room. Here I was in the airport, nobody there to meet me, I don't speak Arabic, and I had no hotel. I finally found a cab driver who spoke a little English. He took me downtown, to a small hotel that he thought might have something. It was full, but fortunately, one fellow had skipped out without paying his bill, and they let me have his room for the night. Things like that could be a little hair-raising at times. We came back to the States in 1976.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's backtrack to World War II, to the island of Okinawa.

Earl A. Luehman:

Naha, the capital, was absolutely leveled, just rubble. It was an unbelievable sight. We got word that about a third of the island had been secured, so like a bunch of dummies, we hopped in the jeep, each with a 30 caliber carbine, and charged out to see what the landscape looked like. There were airplanes that had been shot down and crashed. Of course, there could have been snipers up in the hills and we were just riding around.

The day they dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, we knew nothing about it. I happened to be on a patrol, about twenty miles west of Japan. I looked over to the east and I saw this orange-reddish color spreading over the whole horizon. I didn't know what it was.

I came back and they said, "Hey, did you hear? They dropped some big bomb up there." Later, I learned that was the atomic bomb.

Donald R. Lennon:

The following conversations were related while looking at World War II pictures.

Earl A. Luehman:

After VJ Day, a typhoon blew up just east of Okinawa. It was a big one, so strong that it peeled back the forward portion of the flight deck of the carrier PRINCETON. In order to track its path, the Army Aerologists wanted a plane to fly out to its center. Guess who got the job? They said, "The best way to do this is to fly at eight hundred feet." Of course, for a pilot that is the worst thing to do. As we flew out, we changed directions everytime the wind changed, on the quarter. We ended up following the tail wind and we flew right to the eye of the storm. I remember the beautiful sunlight. We could see the funnel shape and the birds flying around. The water was so white that we couldn't see anything. There was no blue water at all, just white caps. We hit the other side and came home. I can't remember the time, but we were averaging over six-hundred miles an hour, out and back, by following the tail winds.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where are you located in this picture?

Earl A. Luehman:

That looks like the fleet outside of Okinawa. That was taken from the elevation at the end of the runway, because this is where I came down and came out over this fleet. This is where they gathered when they were worried about kamikazes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you shooting that from your B-24?

Earl A. Luehman:

I don't know how I got that. I really don't.

We had intelligence that Japanese were transiting a submarine from Alaska to the West Coast. We were at Midway at the time. I took off one night at midnight. I was

supposed to fly at about two-thousand feet and search for this sub between Adak and Midway. To make a trip of this length and time, we had to use the two internal gas tanks that were installed for that purpose. They were on a rack right behind the pilot and co-pilot. The problem with them was that on occasion, if we had to drop them, they would hang up. If we were trying to land, it became very difficult with these gas tanks hanging half out of the airplane. About two hours out, we lost one engine, started to turn back, and lost another one. We had lost two engines on the same side. I was trying to keep the airplane flying. I tried dropping my bombs to lighten the load, but I did not want to drop the gas tanks because I didn't know what would happen. This airplane was barely flying. Midway is only about eight feet above sea level. We had radio direction finders and I finally saw the lights. I was still struggling with this thing to keep it in the air. We got permission to land on one of the runways. I said to my co-pilot, "Look, line me up with the runway."

There were two runways and this idiot got me lined up on the wrong one. I looked up just before I was about to land and there was a Goddamn jeep parked on the runway. I barely got the plane turned and landed on the proper runway. We were going like hell because I had to use my full power to land. I touched the brakes and I didn't have any left. I couldn't slow the bastard down. Reversing the props didn't help any. The end of the runway was coming up. There was a twenty-foot drop-off at the end of the runway. I added power to the two starboard engines and ran off the runway.

[End of Interview]