| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

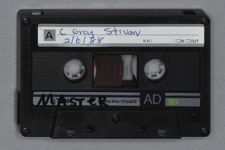

| Captain C. Gray Strum | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| February 6, 1988 | |

| Interview # 1 |

Morgan J. Barclay:

Captain Strum, let's start with a little bit of background information. You're a native of Florida, right?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. A native of Jacksonville. Actually, I was born in St. Petersburg. We lived there for six weeks, then we moved to Jacksonville.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did you spend your youth in Florida?

Charles Gray Strum:

I spent my early youth in Jacksonville. I lived in Tallahassee for six years and then moved back to Jacksonville to complete junior high school and high school before going off to the Naval Academy.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What prompted your interest in the Naval Academy?

Charles Gray Strum:

I had several interests to sort out in my early life. At first, I considered becoming a priest. My grandfather, for whom I am named, was a priest. Secondly, I thought of becoming a lawyer, because my father was a well known jurist. My father also served in the Navy in World War I, and that prompted my interest in the Navy. Finally, the Naval career won out. During my last year in high school, I attended the Bolles school here in Jacksonville, which was a highly rated academic school and it helped tremendously in preparing me for the Naval Academy.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Then you went off to the Naval Academy.

Charles Gray Strum:

Actually, one more year intervened while I attended Columbia Preparatory School in Washington for a year. Then I entered the Naval Academy in 1937. Unfortunately, I was a three-and-one-half-year student.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That class got cut short, didn't it?

Charles Gray Strum:

Right.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Can you tell me a little bit about your experiences at the Academy--what you liked and disliked, subjects, activities?

Charles Gray Strum:

That's a hard one to answer in short order.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Well, it doesn't have to be short order.

Charles Gray Strum:

My last year in high school was at a military school so I had become accustomed to that. Plebe year was something to be endured. Things got better after that. My main athletic interests were in swimming and being on the gym team. I had no unusual interests other than simply keeping my head above water and staying ahead of the academics.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I gather from interviewing other people that there is a lot of pressure both academically and disciplinarily to keep you going.

Charles Gray Strum:

Quite a lot, yes. We lost some classmates early in the game. Some of them hardly lasted through the first summer.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What percentage of the class would you end up losing the first year?

Charles Gray Strum:

I don't know about the first year, but we had 585 classmates when we started, we had 385 graduates. So, the attrition was about thirty-three percent roughly.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Some of that could have been the vision situation.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. I would say that probably half of those who left went during the first year.

Another fourth went during the second year. Once they got past the second year, they pretty much had it made if they just stayed out of trouble and worked enough.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You graduated in February, 1941?

Charles Gray Strum:

That's correct, February 7, 1941.

Morgan J. Barclay:

From there, where did you head?

Charles Gray Strum:

Okay. We took a month of well-deserved vacation. Then I went directly to the Pacific Fleet. I boarded a transport ship to Pearl Harbor and arrived there in March. My first duty was aboard the USS PENNSYLVANIA battleship, which was the flagship for the Pacific Fleet.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You started there in March of 1941?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What was your first assignment and how did you like the PENNSYLVANIA?

Charles Gray Strum:

My first assignment was in the communications division. I liked the PENNSYLVANIA fine. I had done a couple of cruises in battleships while I was a midshipman. The PENNSYLVANIA was a fine ship. Of course, in those days, she was a showplace. It was Admiral Kimmel's flagship, although we didn't see much of him. He had his headquarters ashore. The time was spent in periods at sea for training and short periods back in port. It was a period I enjoyed very much.

I had a brother who was in the Class of 1940 and he was out there. I forget which battleship he was in. I think it was the NEW MEXICO. He and I and a third member of the Class of 1940 bought an old 1939 Chevrolet touring car out there. It disappeared on December 7. We never found it. It was an enjoyable time, but early on, the tension began to develop and people could sense that something was going to happen.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Obviously, the tension was building and you could read some of that even in the newspapers, but did you have any idea that December 7, 1941, was coming?

Charles Gray Strum:

I didn't and I was in a communications division. I saw the classified messages and de-coded them, but I didn't see anything that indicated that it was imminent. As I said, there were general feelings of tension, but nothing specific. I was as surprised as anybody else.

Morgan J. Barclay:

While you were on the PENNSYLVANIA, was your home port in Pearl Harbor? Did you go in and out and do the training exercises there?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. We were one of the fortunate ones. Being the fleet flagship, we tied up at a dock on the island of Oahu rather than Ford Island. We didn't have to ride the boat ashore. We just walked off. We had a very choice berth.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Where were you and the PENNSYLVANIA on December 7?

Charles Gray Strum:

The PENNSYLVANIA had quite a stroke of luck. On December 6, the day before the attack, we moved from 1010 pier, which was the flagship's normal place to tie up, two hundred yards straight ahead to drydock to have some underwater work done. Apparently there was not enough time for Japanese intelligence to know that; they thought we were still at 1010 pier. As it happened, the HELENA and the OGLALA had moved to the pier that we had vacated. The HELENA was sunk and the OGLALA was capsized. It really took a pounding. On the other hand, having moved into drydock, we were not an assigned target in that location; however, we were worked over by the airplanes assigned for targets-of-opportunity. We didn't escape unscathed, but we didn't get the ferocious blow that the cruiser HELENA and the OGLALA did.

Morgan J. Barclay:

They were able to patch up the PENNSYLVANIA?

Charles Gray Strum:

It was about two weeks before we could get underway--get out of the drydock and

back to San Francisco for repairs. As I recall, we took two direct hits. The CASSIN and DOWNES, two destroyers that were in the drydock right ahead of us, were totally destroyed. (I had had dinner the night before with a classmate on the CASSIN, and he was killed the next morning.) As they exploded, their torpedo air flasks were thrown up in the air and when they dropped down, they landed on our fo'c's'le. Those things were charged to about two thousand pounds per square inch of compressed air. It was like being hit by a bomb. All the fo'c's'le on the ship was torn up. We took two hits roughly amidship and one on the drydock that sprayed us with a lot of debris. I think we lost seventy-five men in the PENNSYLVANIA.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That was a sizeable number of casualties.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. As I said earlier, I grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, on a street called Avondale Circle. A lieutenant commander in the PENNSYLVANIA with me lived right on the other side of Avondale Circle--he was my neighbor--and he was killed that morning.

One of the vivid things that I remember is that a torpedo plane started to lay a torpedo up to the drydock caisson so it would flood it and ride us up over the top of the two destroyers ahead of us. We hit that plane with a three-inch fifty gun. It is the only thing I ever saw a three-inch fifty hit. That torpedo plane disappeared in a flash. The PENNSYLVANIA would have been very heavily damaged if that plane had not been shot down.

Morgan J. Barclay:

It was a good shot at the right time.

Charles Gray Strum:

Exactly. It took about two weeks to patch the ship up well enough to get out of the drydock and get underway.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You had to limp back to San Francisco. How long, approximately, were you there for repairs?

Charles Gray Strum:

We were there, roughly, for six weeks. It was a very enjoyable six weeks, I might say.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Then you went back to the Pacific?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. I don't remember the dates, but the next thing we got into was the Aleutian Islands invasion. It was a very tightly kept secret. Nobody knew where we were going or when we were going. I remember shortly before the ship got underway, some mysterious-looking crates appeared on the dock, and somebody wanted to bring them aboard.

The officer of the deck said, "Wait a minute. You can't bring those aboard until I know what is in them."

The person said, "Ah, I can't tell you what is in them."

They got the captain up there and he looked out and said it would be okay. So they brought the crates aboard and put them in the captain's cabin. It was not until we were at sea and in radio silence that the crates were opened. Inside were great huge relief maps of the Aleutian Islands. They assembled these in the captain's cabin, and it became the "Nerve Center" for planning the attack on the Aleutian Islands.

We stayed at sea for six weeks to conceal our location and intent. Our first port call was Cold Bay in the Aleutian Islands. Since we had been at sea for six weeks, our executive officer sent his aide ashore to see if we could put a liberty party ashore. I was officer of the deck at the time. When the aide came back and reported to the executive, he said, "Commander, you had better invite those dog-faces to come aboard the ship."

He did and we took a couple hundred aboard at a time and let them take a bath and

eat a steak and ice cream. Then we sent them back. This was a secure port. There were no communications from there so we were not revealing anything. We stayed there for a couple of days and then went on for the invasion of Attu and Kiska.

Morgan J. Barclay:

The PENNSYLVANIA served as the communication center and planning center.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Were you also involved in support of the actual invasion and the bombing?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. Well, Naval bombardment as opposed to aircraft bombing. All we had was observation airplanes. We had some attack airplanes along with us, but not in the PENNSYLVANIA.

When we were in San Francisco, the navigator of the ship threw away his dead-reckoning tracer, which is a piece of navigation equipment. He was replacing it because it was outmoded. I saw it on the pier and rescued it. At that point in time, I was the radar officer of the ship. We had vertical radial displays, but I wanted a horizontal plot that would show our absolute location. So, I rescued this dead-reckoning tracer, and while we were in San Francisco, I designed and built a combat information center which is much like what you see in ships today. I took the tracer and set it up so that I could have a piece of transparent paper on top of it. Then I replaced the pencil with a tiny light bulb that would move along underneath the paper. I could lay a map on top of the paper and put a dot where the light was and track where the ship had been. More importantly, we could see where it was in relation to the land.

When we started to invade Kiska, as luck would have it, we had dense fog. (Well, it wasn't luck because in the Aleutians that happens all the time.) We were being called on for shore bombardment, but nobody could see anything. The skipper asked me if I could run a

shore bombardment from the combat information center.

I said, "Yes, Sir. I sure can."

As far as I know, that was the first time anybody had done a radar-controlled shore bombardment. I scanned the shoreline and, about every five degrees, plotted the range and bearing to shore. They all came together at one point, which very precisely fixed the position of the ship. I just measured from there to wherever the target was and gave them the range and bearing to shoot. I'll never forget the first salvo we laid in there. Nobody trusted us. They called on us to fire within about five hundred yards of our own troops. I guess I was a little nervous about it myself, so I added about a thousand yards to the estimated range.

The shore fire-control party came back right away and said, "Down one-o double-o, no change."

That meant: Down 1000 yards; you are on bearing, start with rapid fire. It was very, very successful.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You put the dead-reckoning tracer plus the radar together.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. We brought it all together in the combat information center and provided the range and bearing information for the bombardment. I was thrilled with that. It worked fine.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were glad you rescued that equipment! Did your ship also have sonar?

Charles Gray Strum:

No. We didn't have sonar at all. I recall one time a PBY airplane flying around us and using our communication code name, called to tell us a torpedo was heading toward us. He said nothing about where it was--range, bearing, target angle, or anything. All the

skipper could do, poor guy, was to try to change something.

He said, "Flank speed, hard right rudder."

Sure enough, we looked down over the side and saw that torpedo go right by us.

Morgan J. Barclay:

It just missed you?

Charles Gray Strum:

It just barely missed us.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were involved in the shore bombardment and support of the invasion. At that time, were you the ship's communication officer?

Charles Gray Strum:

No, I was not the communication officer at that point. I had become the radar officer and what you would now call a combat information center officer.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long did you stay on the PENNSYLVANIA with this duty, approximately?

Charles Gray Strum:

Three years. I started trying to get off to go to flight training, but the skipper thought that I was the only one that could run that radar. I would send my request for flight training back aft and it would get lost. I didn't get to flight taining until the end of 1944.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What prompted your interest in flight training?

Charles Gray Strum:

I had always been interested in aviation. When I was a second classman at the Naval Academy, I came home in September on leave, and a friend of mine with whom I had grown up had taken flying lessons withthe intention of joining the Army Air Corps. So I took flying lessons from a very famous aviator here in Jacksonville, named Larie Young. He taught me to fly a Piper Cub. I got it in my blood. Then I wanted to get into military aviation. Finally, I did.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Because the skipper felt that you were the only one who could run the radar, how long did you stay with the PENNSLYVANIA?

Charles Gray Strum:

Until December, 1944.

Morgan J. Barclay:

He wasn't going to let you out then?

Charles Gray Strum:

He really hung on. We had three officers in the division, and he finally agreed to phase us out, one by one, if we wanted to go.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What other principal activities and battles do you remember with the PENNSYLVANIA?

Charles Gray Strum:

The only other one that I remember was the bombardment and invasion of the islands of Makin and Tarawa. We were principally involved in Makin, although when we finished there, we steamed on over to Tarawa for the mop-up phase of that.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That involved coastal bombardment again?

Charles Gray Strum:

Bombardment and support. This time we could see, however. We didn't need the radar.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Then you could see what you were shooting. Did you have a lot of problems with kamikaze attacks?

Charles Gray Strum:

Kamikazes hadn't started quite that early.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did you face a lot of fire from the Japanese?

Charles Gray Strum:

In Makin, we got shot at from the shore. Mostly though, we were concerned about submarines. After Pearl Harbor, however, the PENNSYLVANIA was not hit while I was aboard. I think she may have been hit out at Okinawa, but not while I was there.

Morgan J. Barclay:

The PENNSLYVANIA did pretty well in that regard. I know a lot of ships faced air attacks.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes, especially later in the war.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You managed to get off the PENNSYLVAINIA in 1944. Where did you go to

flight school?

Charles Gray Strum:

I went to flight training in Dallas. One of the first people I saw there was Hoke Sisk. (He was working with me on this [reunion] and we're now neighbors here.) I finished the early, elimination-base training and went to Pensacola for primary flight training. They asked me what I wanted to fly, and like everybody else, I said that I wanted to be a fighter pilot.

They said, "Fine, there are the PBYs over there. You can go fly one of those."

In retrospect, it was a good thing because if this had not happened, I would have never met and married my wife. I finished the primary training in Pensacola and then moved to Jacksonville. By this time, I was a very senior lieutenant and about to make lieutenant commander. They wanted me to accumulate some flight time, so when I finished the advanced phase of training in Jacksonville, they kept me on as a flight instructor.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Is that where you met your wife?

Charles Gray Strum:

It was because I was in the PBY business that I came back to Jacksonville for another tour. That's where I met her. If I had gone the fighter route, I would never have gone back to Jacksonville.

Morgan J. Barclay:

After you finished your flight training and you were an instructor, then where did you go?

Charles Gray Strum:

I went back to the Pacific again. I got orders to be the commanding officer on an LST, of all things. The war was just about to end at this point. As a matter of fact, it did end. This was in August 1945.

I got to Pearl Harbor to take command of this LST and found that I was senior to the

division commander. I sort of objected to this and they rewrote my orders and sent me out to Sangley Point in the Philippines to be the executive officer of a PBY squadron, which is what they should have done in the first place really.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long were you in the Philippines?

Charles Gray Strum:

We were out there for about six months. Mainly, we flew patrols out there to the north, looking for floating mines and things like that--remnants of the war that might be dangerous. Also, we were involved with the people who were trying to get back to the States and muster out. There was a big camp in the southern Philippines that was a staging area for all the Army people. Every Friday, we would fly a whole squadron of PBYs down there and spend Friday night. On Saturday morning we would load up with as many dogfaces as we could and fly them up to Baguio, which was a resort in the northern Philippines. It was five thousand feet up and it was probably ten degrees or so cooler. We would drop them off, pick up another load, fly them back down to Guiuan, Samar, spend Saturday night there, and then go back home on Sunday. That was a big part of our activity--just staging the soldiers to give some relief from that hot messy place they were in down there.

We had about six months of that and then we brought the squadron back to the States. That was an interesting experience. As the executive officer of the squadron, I didn't have my own flight crew. I just moved around from one to another, wherever I was needed. They had an extra airplane that had been sitting down there in the southern Philippines on an old airfield, completely unattended. It had not been maintained but somebody had to fly it back to the States.

They said, "Hey, you go down there and get that airplane."

I brought it back up to Sangley Point.

As I taxied up the ramp, this old chief was looking at me and said, "Commander, are you going to take that plane back to the States?"

I said, "Yep! Are you ready to muster out?"

He said, "Yes, Sir."

I said, "Well, you're going to be the crew chief on this plane."

It was in awful shape. It had been sitting down there with no battens on the controls and all the control cables were stretched. This chief rolled up his sleeves and started working on that airplane. He got it in as good a shape as he could. On the first leg of the flight back, however, we lost all the hydraulics. There were no brakes on the airplane so we made "no-brake" landings all the way back across the Pacific. There were no maintenance facilities, they were all closed up. There were no weather forecasters--we did our own forecasts.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Out the window!

Charles Gray Strum:

It was a very, very interesting flight. Anyway, we had a lot of fun. I enjoyed Sangley Point. I liked the Philippines, and later on I went back to be commanding officer of the Naval Sation in Sangley Point. I also became an honorary citizen of the Philippines.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I would think that would have been quite a scary experience--dealing with an airplane that obviously hadn't been serviced or taken care of.

Charles Gray Strum:

Not only that. I had thirty-two people in that jewel. It was packed like sardines. It was a very thrilling flight.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You had to make it all the way back to the States with no brakes?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes, there were no hydraulics.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What was your next assignment after you came back from the Philippines?

Charles Gray Strum:

Actually, they were going to decommission the squadron at Kaneohe Bay in northern Oahu. That was our destination from the Philippines. In mid-flight from Midway Island we got a message that said to land at Ford Island instead of Kaneohe Bay; so we went to Ford Island.

There was an aircraft carrier there and someone met us and said, "You know, instead of decommissioning, they're going to put you on this aircraft carrier and take you to the West Coast to San Diego. Then the squadron is going to Norfolk, Virginia, for duty."

This was shocking news because we thought we were going to decommission outside the continental limits of the United States. Nobody had paid any attention to inventories, spare parts, or anything else; and then we were faced with keeping those airplanes going for an indefinite period. They loaded us aboard the carrier and took us to the West Coast. We flew on to Norfolk and started trying to put the squadron back together. I stayed for about six months; however, the squadron stayed on long, long after that.

At that time, I left to become commanding officer of a utility squadron in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When would that have been approximately?

Charles Gray Strum:

This was in 1946. In those days a tour as commanding officer was one year because it was very much in demand. I enjoyed Guantanamo. It was a nice, nice base. I was still a bachelor and I had the aviation detachments in San Juan, Puerto Rico; Key West; Miami; and Jacksonville. I inspected one of them every weekend.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were on the go all the time.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes, I had a wonderful time with that tour. Interestingly enough, we had a variety of airplanes. I think I flew more Air Force-type airplanes than Navy airplanes during that period.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Is that because they were more available?

Charles Gray Strum:

They were used for special purposes. The old "Billy Mitchell" bomber and the "Invader," the A26, were especially well-suited to towing targets. We towed the aerial targets for the Fleet gunnery practice. They were well-suited for operating pilotless aircraft and drones. We used them as control planes. We had a large detachment of drones and pilotless aircraft.

Morgan J. Barclay:

These were used primarily on training exercises.

Charles Gray Strum:

As aerial targets.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Where did you go from Guantanamo?

Charles Gray Strum:

From Guantanamo, I went back to Norfolk, Virginia, to be on the staff of Commander Utility Wings Atlantic, which was the parent organization of the Squadron I had commanded. I was there for one year. At this point, it was discovered that my mother, who lived in Jacksonville, Florida, had a fatal illness. I called up my friend, Stu Sterling. (Stu is one of the other three hosts here at this reunion.) He was on the lieutenant commander desk at the Bureau of Personnel at that time. Stu wrote me up a set of orders to Jacksonville, Florida, for humanitarian reasons. My mother passed away within six months, but I stayed for a full tour in Jacksonville. I was the administrative officer of the Naval Air Station.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Were you responsible for administering the whole station?

Charles Gray Strum:

It's surprising to look back and see what a lieutenant commander was doing in those days. I was responsible for all administrative functions; paperwork, filing, clerical assistants, and all that. In addition, all the WAVES, women's units, reported to me. I was in charge of all the officers' clubs, the chiefs' clubs, and enlisted men's clubs. All the morale and recreational welfare fuctions were part of my responsibility. It was quite a responsibility.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I imagine it was interesting.

Charles Gray Strum:

It was a lot of fun. At that point in time, I had a secretary who at the end of my three-year tour, married me.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You had a full tour in Jacksonville?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. This was from 1948 to 1951.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Where did you go in 1951?

Charles Gray Strum:

In 1951, there was a little interim tour that was unimportant. My major assignment was to put a Fleet aircraft service squadron into commission in Quonset Point, Rhode Island. We moved up there in March and spent the summer in Quonset Point, which is a beautiful time to be there. The rumor was that we were going to move out and be stationed on Bermuda. This sounded fine and we were getting all equipped with summer-type things when all of a sudden we received a message that gave us forty-eight hours notice to move out to Iceland!

Morgan J. Barclay:

Oh no, forget that summer gear!

Charles Gray Strum:

Right! I had forty-eight hours to get my wife home. She was pregnant by this time. I dropped her on my sister's front doorstep in Jacksonville, flew back up to Quonset Point, and then headed to Iceland. One year! No dependents! No leave! I just stayed up there in

that ice-bound place.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was it basically a patrol function?

Charles Gray Strum:

We provided maintenance services for any patrol squadrons that were stationed there.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I imagine that would have been a lonely tour at the time.

Charles Gray Strum:

It was. I'm not even going to call it interesting. The only interesting part were the base functions. They were operated by the Air Force, which was a very new service and very jealous of their position. There was a lot of jockeying back and forth for prerogatives and dates of rank and things. We had a lot, I won't say tension . . . I guess maybe I should say tension. We had a lot.

I was up there for one year. Before going I had talked to my wing commander in Quonset Point. I had said, "Listen, I know there is no leave granted from up there, but this is my first child and my wife is at home pregnant by herself. My father and my sister are in Jacksonville; they'll get her to the hospital and take care of her, but I want to get off when she has that child."

He said, "Okay, you write yourself a set of orders with no date that orders you back to Quonset Point for temporary additional duty to consult on personnel and administrative matters."

I did this. As soon as I got the word that I had a daughter, I put a date on that set of orders and headed for Quonset Point. Bless his heart, he had an airplane sitting there at the end of the runway with a pilot aboard who needed an instrument check. He was going to do it

en route to Jacksonville. They dropped me off in Jacksonville for a week. Then I headed

on back to Iceland to complete my tour.

Morgan J. Barclay:

It was nice that you could get home.

Charles Gray Strum:

The tour in Iceland was interesting. The Icelanders are very proud people. You don't want to make the mistake of calling them Danish or Scandinavian. They have a thousand-year-old culture of their own. One thing that a lot of people don't understand is that they are pretty heavily Communist-infiltrated. They were even in those days. We didn't have a base in Iceland. We had what was called an "agreed area." I remember that there was no American flag there. All of a sudden, this Army brigadier, who was in charge of all the military forces, and I decided to put up an American flag and see what would happen. We erected a flagpole and hoisted up the flag. Nothing happened for about two weeks. Then all of a sudden, this great tirade commenced in the Communist press up there in Reykjavik. It was obvious that they had had to go back to the headquarters in Moscow to find out what to say about this. We had some interesting things like that to happen which helped to break the boredom. Aside from that, it was a pretty monotonous tour.

Morgan J. Barclay:

There was obviously an influence there. Did you sense that in dealing with the local people?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. You could tell as you walked down the streets in Reykjavik. We were not stationed there but we would visit there occasionally. Four out of five people would tolerate us but the fifth one might try to jostle us or do something to upset us.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That is interesting. Well, you survived the year in Iceland. Where did you go in 1952?

Charles Gray Strum:

Having survived a year in Iceland, the Bureau of Personnel--bless their heart--said,

"Having done that, where would you like to go?"

I said, "Jacksonville, Florida." I came back to Jacksonville and I had a tour of duty as first operations officer and then executive officer of the Naval Air Reserve Training Unit.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What were the duties involved in those assignments?

Charles Gray Strum:

Well, operations officer of NARTU was something more than operations officer of a squadron. We also had the responsibility for training the reserve pilots. We checked them out in different kinds of aircraft, maintained their skills, as well as just looking out for the operation. We had something like eight reserve squadrons that functioned off our support base.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How many personnel did that involve?

Charles Gray Strum:

It was huge. There were not too many of the so called station-keepers. We had something like two hundred. But I would say there were probably something like two thousand reserves. We covered not only Jacksonville, but also places like Tallahassee and Charleston. We went to a different place every weekend. We would fly the airplanes to where the reserves were and work for the weekend, and then we would bring the planes back.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You would be training and maintaining skills and also introducing new aircraft and technologies. How did you like the training function?

Charles Gray Strum:

It was interesting. I enjoyed it very much indeed. I enjoyed it more than I did being executive officer. That was kind of routine. I got to do a lot more flying as operations and training officer and I loved that.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Anytime you can get up into the air. . . .

Charles Gray Strum:

That's right.

Morgan J. Barclay:

From Jacksonville, where did you go?

Charles Gray Strum:

From Jacksonville, I went to Pensacola to be the navigator of the training carrier the USS MONTEREY.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were on a carrier then.

Charles Gray Strum:

This was a CVL, a light carrier, built on a cruiser hull.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That would have been about 1955 or so?

Charles Gray Strum:

This was in 1955.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were the navigator for a training carrier.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. This was interesting. This was the first time I had been back on a ship since my early days. I don't know how much you know about what a navigator does, but in addition to just keeping track of where the ship is, he also makes recommendations on the actual control of the vessel. The captain can either accept the recommendation or not, but most often he does. The MONTEREY had a draft of twenty-nine feet, six inches at its lowest point, which was the aft under the ship. We had a channel that we ran twice a day, five times a week. It was a published thirty-foot channel, which only gave us six inches to spare. It was a fairly narrow channel, too. Running this channel enabled one to become very good at ship handling.

Morgan J. Barclay:

One would get some gray hair doing that.

Charles Gray Strum:

We had to run at fifteen knots, no faster and no slower. If we went slower, we didn't have enough steerageway. If we got any faster, the ship's stern would bounce off the bottom of the channel, because she was sort of squat. Once we got going, there was no turning back. We ran that thing fifteen knots all the way. We would send helicopters out ahead to

make sure that no one else was in that channel until we were through. It required a lot of seamanship and a lot of skill, but it was very enjoyable, particularly when there were strong winds or heavy seas or anything to complicate the problem. I stayed in close touch with the Pensacola Bar Pilots' Association although we never used pilots in the ship. Because of my close relationship with them and the knowledge they had of my running that channel many, many times, they offered me an honorary membership in the Pensacola Bar Pilots' Association when I left. I was there for one year.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Having spent most of your career as an aviator, how did you like getting thrown back into the navigator's position?

Charles Gray Strum:

I loved it. I really loved it.

Morgan J. Barclay:

It didn't irritate you that you got thrown back into that role?

Charles Gray Strum:

Not at all, particularly since I was in an aircraft carrier. I was at least tangentially in the aviation-training process.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You would be involved with some of the training going on with the aviators as well as navigation duties.

Charles Gray Strum:

I was allowed to maintain my pilot's skills during the period, too--not allowed to, required to.

Morgan J. Barclay:

So you could fly, too.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes.

Morgan J. Barclay:

After the MONTEREY, where did you go?

Charles Gray Strum:

We went to Patuxent River, Maryland. I checked into a squadron which was forming up. It was a new concept: Airborne Early Warning. We flew "Super Constellation" aircraft. They called them the "pregnant guppies." The Constellation, I

thought, was the most beautiful airplane I had ever seen. Then they started hanging radar all over them and they really did look pregnant. They had radar underneath and radar on top, too. They were monstrous squadrons.

By this time, I was getting to be a moderately senior commander and I had had five commands of my own. I was, however, about the number four boy down in this squadron. The squadron had a four-stripe captain in command and was top-heavy with three stripers. The flying was good. We had some expert instructors. I think I really learned more about flying then than at any other time. The guy who was my instructor wrote the book on the airplane, and I mean "literally" wrote it. He wrote the training manual. I'll never forget my " aircraft commander check-out" in that thing. It was a four-hour flight, but for the first two hours, we never even got off the ground with all the simulated emergencies this guy pulled.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Just to see what you did under the gun.

Charles Gray Strum:

Just to see what I would do. Then we took off and we flew the heavily travelled airways between Baltimore and Washington, and Baltimore and New York. We had single-engine emergencies all the way. We came back and made a two-engine emergency landing. I would be just about to land and he would say, "Sorry, go around again." Here I was with no hydraulics and only two engines and would have to go around again. It was a tremendously demanding training but a lot of fun. I learned a lot.

Once we finished the training phase, these squadrons were deployed to Argentia, Newfoundland. We went up there for three months and flew a barrier patrol from Newfoundland to the Azores and then back to Newfoundland. The theory was that if we kept a constant radar barrier, we would detect any Soviet vessels exiting from the North Sea and heading down to the Atlantic. We would fly twenty-four-hour missions. They lasted

twenty-four hours by the time you had your pre-flight briefing and your post-flight briefing. Because of the long flight, we would fly the airplanes twenty-two thousand pounds over their maximum designed weight. We knew this.

Also, the squadron's instrument standards were tough. If you could see only one runway light when you went to the head of the runway, you had to wait until you saw two lights before you could go. That's a hundred fifty feet visibility. It was a very demanding type of flying.

The positioning of the radar picket airplanes had to be precise and they had to be there all the time. They couldn't afford to miss anything. We went in all kinds of weather, and Newfoundland had some of the nastiest weather you've ever seen in your life.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You would be flying regardless of the weather. You had to keep that picket up.

Charles Gray Strum:

That's right. If I saw only one light out there, I had to wait unti a little bubble came across the field. As soon as I saw two lights, off I would go.

I don't know about the value of the operation. But there certainly was a great psychological value in opposing anything that the Russians were using. I think it was pretty valuable, too, in terms of the intelligence we gained. It was tough on crews at first. We would get up there, take off from Newfoundland, fly to the Azores, then back to Newfoundland, and then I would say, "Okay boys, let's do it again." The weather was always nasty. It was tough flying but we enjoyed it. We spent three months on station there and then three months back in Patuxent River, training additional flight crew members and rotating crew members.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You mentioned that these were twenty-four-hour flights. How many of these hours would be flying time?

Charles Gray Strum:

About twenty hours. We took double crews. There would be only one aircraft commander, but beyond that, every position was duplicated. We had two first pilots, two navigators, two flight engineers, and so on.

Morgan J. Barclay:

The pilots would be alternating during that twenty-four hour time?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes, all except the aircraft commander. He had the responsibility for the whole flight. They were comfortable airplanes. We had bunks to sleep in and a galley to cook food.

Morgan J. Barclay:

They were long shifts and you couldn't afford to make any mistakes in that weather.

Charles Gray Strum:

They were very careful. As an example, our squadron doctrine required that the aircraft commander and the first pilot eat different menus. They were not allowed to eat the same thing. If there had been any food poisoning, they would not both be sick at the same time. They were very thorough about things. That went on for about a year. Then we finally had to do our penance: a tour of duty in Washington.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That's the main reaction I get from everybody about Washington. What was your assignment in Washington?

Charles Gray Strum:

I was the test aircraft distribution control officer for the Bureau of Aeronautics. I controlled the distribution of all test and development airplanes. For example, we had all the flight-testing and weapons-testing divisions at Patuxent River. We supplied the planes for them and for all the missile programs at Point Mugu. I guess I had an inventory of about five hundred airplanes that I manuevered around.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You assigned what airplanes would go where, where the new ones would go, and which ones would get withdrawn.

Charles Gray Strum:

That's right, including the purposes of the projects they were going to be engaged in and what instrumentation had to be installed. All of our planes were a special configuration.

Keeping my flying proficiency while in Washington was tough. I had to schedule flying time through Anacostia, and if for any reason I cancelled a flight, they would move me down on the priority list and I would have to go out there at midnight to fly. So I got a little T-34 airplane, installed some engine instrumentation in it, and put it down at Quantico at the Marine base. I knew the general down there was a private pilot.

I said to him, "Now, General, you can fly this airplane just so long as I can fly it whenever I want to."

I kept my flight proficiency through the Marine base with the test and development airplane. It was one little bonus that I got. It was an interesting tour because I was able to supply hardware for a lot of the experimental projects. Incidentally, during this period, I supplied some airplanes for a Marine major named John Glenn. He was right down the hall from me a couple of doors. He was what we called a "class desk officer" for Marine fighter airplanes. I remember when John Glenn dropped out of sight. Nobody knew where he was for about six weeks. When he came back, he had been selected to be an astronaut.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I imagine during your career, you saw a lot of changes in the technology. Maybe you could discuss some of those changes in aircraft in laymen's terms.

Charles Gray Strum:

The first airplane that I flew in Dallas was called a "Yellow Peril." This was an open-cockpit two-seater biplane. It was cold. I was there in December and I'll never forget how that wind whooped across the plains there in Grand Prairie, Texas. It had an inertia

starter. I would have to stand up on the wing to crank this thing. I would crank and crank and crank. It was tough! It was tough to get the thing moving. Finally, I would get it up to speed and it would whine and the pitch would get higher and higher. I would recognize by the pitch whether or not it was going fast enough, then I would jump back and tell the fellow to start the airplane. He would turn the switch and it would grind and grind until it finally quit. Then I would have to do it all over again. The "Yellow Peril" was a lot of fun to fly. It was an especially good aerobatic airplane. We used to fly in fleeced-lined leather jackets.

Morgan J. Barclay:

And you were still cold.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. We were still stiff from the cold. My favorite airplane of all time was the "Super Connie," which was a beautiful airplane. I would go anywhere, anytime, under any conditions in that airplane.

I finally got into jet fighters while I was stationed in Washington. I requested temporary additional duty to go out to Olathe, Kansas and get a jet check-out. I felt that in order to distribute these airplanes, I ought to be able to fly them. I got the jet check-out and enjoyed that. I went all the way from the little "Yellow Peril" up through the F9F jet fighter.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Why was the "Connie" your favorite?

Charles Gray Strum:

It was just a beautiful-looking airplane. The passenger-configured airplane had such smooth flowing lines. It had three tails--three vertical fins. It was just a nice beautiful curving body. It just was a gorgeous thing to see. The F9F jet fighter was a lot of fun, too. I enjoyed it. But the "Connie," with her instrumentation and flight characteristics . . . I would just go anywhere anytime in that plane. That was the airplane we flew during all that

nasty weather up in Newfoundland. I just had a lot of trust in that airplane.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You put in a lot of hours on it.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes, I sure did.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What kind of changes did you see in the technology? For example, in navigation and radar?

Charles Gray Strum:

Here in Jacksonville, we have several paper mills, But back in the early days, we had one paper mill and it smelled awful. If you were to come in here under instrument conditions, and if there were low hanging stratus clouds, which are flat on the top, you could see where the paper mill was by the smoke poking up through the clouds. You knew where you were. You knew that you were fourteen miles northeast of the Naval Air Station in Jacksonville. The thing to do was to turn straight east, because this paper mill was right on the coastline, and you could fly east about five minutes and be certain that you were over water. Then you could let down through the clouds until you could see a little better where you were going.

Later, we came up with what would now be considered very rudimentary navigational aids. When someone coming in on an instrument flight plan to Naval Air Station, Jacksonville, got over the Jacksonville municipal radio range, he would call in to the flight controller and say, "I'm over High Cone. I request clearance to Naval Air Station, Jacksonville."

The controller would say, "Fine, sir, you are cleared out of the control area southwest, twelve miles. Good-day, sir."That translated meant that you were on your own. There was no approved instrument approach to the Naval Air Station in Jacksonville. They had a radio range there

but the FAA had not approved it, and it was years before they did. They would just clearly say, "Sorry, Bud, it's been nice talking to you. Go to it. Good luck."

Those were some of the earlier days. I remember when we got our first radio compass in the airplane. That was really something. Of course, it's passe' now. Now days with Loran navigation and some of the electronic aids, we can pinpoint our positions in nothing flat.

The shipboard navigator uses a sextant. The instrument used by an aviation navigator was called an octant. It was a hand-held octant. It had a little bubble in there so we could level it. We were lucky to get a position that was in twenty miles of where we really were. Now with the Loran, the long-range electronic navigation, we can pinpoint our positon constantly. We saw a lot of growth in that area. I'll never forget looking for that paper mill that was making all that smoke--trying to pinpoint our location.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You had to do a lot of flying without much in the way of instrumentation. How do pilots, without the benefit of experience, do today when their instrumentation goes out?

Charles Gray Strum:

I don't really know. We felt comfortable because part of our training in Pensacola was what we called needle-ball-airspeed flying. We had a canvas hood that they would throw over our cockpit so we couldn't see. There would be a check pilot in the back seat that could see. We would cage our horizons and our compass, using only an airspeed indicator and this little needle-ball thing that bounced around back and forth, making it real tough to tell what was happening. But we had to fly the airplane under those circumstances. If the airspeed increased, we knew we were going down. If it decreased, we knew we were going up. That was all there was to it. We could put one needle-width slant and that would mean we were making what we called a standard-rate turn of three degrees a second. That

was very elemental, but having done that, we would feel comfortable with the rest. I would think that today the instruments are so duplicated that a pilot would never be faced with that. If he were, he probably would be petrified.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You can pretty much pinpoint your location now. They even have computer screens right in the cockpit and you can see yourself on the screen.

Charles Gray Strum:

They don't have just an automatic pilot, they have an automatic controller. The pilots can sit there with their hands off the airplane and the airplane will land itself, even aboard a carrier.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I didn't know that. I thought you still had to land yourself.

Charles Gray Strum:

You can look through the windows of a test pilot and see him holding his hands up. He's ready to grab the thing, of course, but they can be brought in without a human hand on them.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What was your next tour after Washington?

Charles Gray Strum:

While I was in Washington, I was selected for captain and they offered me command of the Airborne Early Warning Squadron 1, which was on Guam. We were flying the same "Super Connie" airplanes but with a different mission. Actually, we had two missions. One was to be the radar support for the Seventh Fleet. I was a task group commander for the Commander Seventh Fleet. I reported directly to him. The other mission was to do typhoon reconnaissance in the Pacific. We were the same as Hurricane Hunters in the Atlantic, but we were called Typhoon Trackers. It's the same basic phenomenon but about two or three times as much of it. While you have a hurricane season here in the Atlantic that generally lasts from June to September, there is no season in the Pacific. They have them all year round. They are more frequent sometimes than other

times, but there is always something happening. You know how they give them names, alphabetically. While you may get A-J over here in the Atlantic, they will go through the alphabet twice out there in the Pacific. We always had at least one that we were working, but usually we had two or three. In fact, at one point, I penetrated two typhoons on the same flight. I took off from Guam, headed for the Philippines, penetrated one, turned northwest and then penetrated one en route to Okinawa. I think I'm probably the only pilot that's ever done that. That was quite a day's work.

I reported to Admiral Donald Griffin who was commander of the Seventh Fleet then. I asked him if he had any special orders for me.

He said, "Captain, you see the same intelligence messages that I do. You be where I need you."

That was that. We had a passenger-configured Super Constellation. Being stationed on Guam, which was so isolated, created morale problems with some of the families. About once every two weeks, I would send an "R and R" plane off to Hong Kong, Tokyo, or some place, if the airplane wasn't needed for some other purpose. Generally, we flew our maintenance crew from one base to another around the Pacific. Wherever the Seventh Fleet was working, we picked the nearest base to them: Sangley Point; Naha, Okinawa; Atsugi, Japan; or wherever. If the airplane was not otherwise employed, I would fly a group of dependents off to Hong Kong or someplace like that. Griffin was very nice to me. He never said no.

I would just say, "Unless otherwise directed, we're going to Hong Kong." He never denied it. But if I had not been where he wanted me, I would have been in a lot of trouble.

We worked with the fleet doing their early warning screening and providing weather

information.

People would say, "Why do you penetrate typhoons? You can stand off and look at them with radar. You know where it is."

The reason is that the only way we could forecast where a typhoon was going was to get in the middle of it and measure the pressure, temperature, and humidity, from the surface up to ten thousand feet. Then we have some basis on which to determine whether it was going to intensify and what direction it was going to take. That was the reason for penetrating it. In those days, we could not over-fly them. Now some of the Air Force planes can over-fly them and let down inside of them.

The Air Force, initially, lost some airplanes because their technique was to penetrate the typhoon at ten thousand feet. Well, it is "rough as a cob" at ten thousand feet. It is tough. They had a couple of airplanes literally torn apart in flight. We would penetrate at seven hundred feet, right down on the water. That required some very precise flying. It was very a nerve-wracking thing. It was rough; the turbulence was sort of like a rough road. Your head would bounce back and forth so that you could hardly read the instruments. But it was not the kind of turbulence of four hundred knots sheer force, which would tear everything apart. While it was very uncomfortable and demanded precise flying, it was without the physical danger of the airplane literally being ripped up. We would get inside the eye and spend about twenty minutes. We would climb from the surface up to ten thousand feet, taking meteorological readings while at the same time giving the crew a chance to clean the airplane up a little bit. Those that still felt like it, could grab a bite to eat. I had quit smoking for seven years, but when I started the typhoon reconnaissance, everytime I would enter the eye of the typhoon, I would light a cigar. When the cigar was

finished, it was time to leave. I went from there back to smoking about fifteen cigars a day. That was one of the bad aspects of it.

Morgan J. Barclay:

The stress!

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. About the penetration, all I can say is that no two typhoons were alike. That's the only generalization I can make. Each one had to be planned for and executed on its own, depending on what you found. Generally, we would get up close to the typhoon and then turn so that we were flying perpendicular to the wind. We would look out the window of the airplane and see wind streaks on the water, and we could gauge when the wind was right off the wing. Finally, it would become a mass of white out there and we couldn't tell where anything was. For the last three to twelve minutes of the flight, we were in the wall cloud, which was extremely turbulent. We had two radar altimeters in the airplane and they read off altitudes all the time. We couldn't trust our barometric reading because the pressure changed so rapidly. We had two radar altimeters so that if one of them went wrong, the other one would still work. We maintained our seven hundred feet this way. Finally, we would break out into the middle of the thing, "the eye," and I would light up a cigar.

It was a very pleasant tour and I enjoyed it very, very much indeed. Guam was a nice place if one didn't feel too confined there, which some people did. The men travelled a lot so it was fun for us. It was the families that had problems.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Were there any dependents there?

Charles Gray Strum:

Oh, yes. My family was there--my wife and two daughters. I remember one time evacuating Guam because a typhoon was bearing down on the island. We took all the airplanes out to the Philippines and then started doing reconnaissance missions. I penetrated this typhoon, was in the eye, and I looked down and realized I was looking at my

own quarters. My family was down there in the eye of that thing.

Morgan J. Barclay:

They were still there?

Charles Gray Strum:

They were still there. In fact, the eye is very calm, so they came outside. I could see them down there. Some families had trouble, but mine didn't. My wife is a good bridge player and she organized card parties.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Some people can adapt. I'm sure it was tough for dependents.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes, in many cases it is. The "R and R" flights helped.

Morgan J. Barclay:

From the information you gathered from your reconnaissance missions, were you fairly accurate in your forecasts?

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes. We were very accurate. We had a typhoon center on Guam that had a bunch of expert meteorologists. We would feed all our information to them and they would make a forecast. (Some of our pilots were pretty good at making forecasts, too.) There was a separate command on Guam just for this purpose. They disseminated for the whole entire Pacific Fleet.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were on Guam for a year? Then from Guam, where did you head?

Charles Gray Strum:

Normally, they would have sent me back to the States; however, the C.O. at the Naval station at Sangley Point, Philippines, was about ready to leave so they nominated me and I went directly out there to become the new commanding officer. I had gone there when I first became an aviator. I was delighted to go back.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What year was that?

Charles Gray Strum:

This was in 1961.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You obviously had some fond memories. What did you like most about the Philippines?

Charles Gray Strum:

It was just a nice place. It was hot, but once you got past that, it was nice. The people were pleasant. I dare say that it wouldn't be as much fun out there now. In those days, people were very friendly. I used to mingle with them a lot. In fact, they even made me an honorary citizen of that country before I left, which I'm very proud of. We had a lovely set of quarters out there. Sangley Point is situated on a peninsula about three miles long. It projects out from the city of Cavite, which is twelve miles southeast of Manila. The airstrip runs twelve thousand feet along this peninsula. Originally, it had been a Naval hospital. The C.O.'s quarters were formerly the nurses' quarters, so it was a gigantic place. We had nice living conditions. We just enjoyed it.

We did some of the early support flights for things that were warming up over in Vietnam. I had a transport airplane and I used to fly supplies over to Vietnam. Incidentally, I mentioned earlier that I became interested in aviation because of a boyhood friend in Jacksonville. During this period, he became an Air Force colonel and the commanding officer of Tan Son Nhut airport, just outside of Saigon. When he came back from tour, he died of cancer in six months. I mention this just to let you know how our careers came back together.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long were you commander there?

Charles Gray Strum:

Two years. I said Naval station, but it really was a Naval air station. We had a mission to support all the Seventh Fleet ships that came in and any SEATO ships. About every six months there would be a joint exercise in Manila Bay and we would have to have a bash for the Australians and others involved in the exercise. It was a very strategic place in the early stages of the Vietnam conflict.

Morgan J. Barclay:

The station would be involved in support of reconnaissance.

Charles Gray Strum:

That's right. The fleet aircraft were stationed there all the time. In fact, we had two patrol squadrons that were permanently based. My old squadron, VW-1, was in and out all the time.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You ran across people you knew all the time.

Charles Gray Strum:

Absolutely.

Morgan J. Barclay:

From the Philippines, where did you head?

Charles Gray Strum:

At that time, my friend Mickey Weisner was on the captain's desk in the Bureau of Personnel. Have you interviewed him? He is the guy in our class who became a four-star admiral. He was first CinCPac Fleet and then CinCPac. He was the "top dog" in the Pacific.

Anyway, when my time was coming up, I wrote a letter to Mickey that said, "How about Jacksonville again?"

He said, "As a matter of fact, the command of the Naval Air Technical Training Center in Jacksonville is coming up. How would you like that?"

I said, "Fine. Sign me up."

We came back to Jacksonville. I had two years. I guess from a personal standpoint, this really was the highlight of my career. The Naval Air Technical Training Center was a rather large organization. We had about five thousand students. We trained people in aviation ordnance; we trained them to be aviation electricians; and we also trained them in a very interesting field, which was in its infancy then, non-destructive testing. We ran a radiology school to learn how to take x-rays of airplanes. It was funny, we would take these x-ray pictures and we would find where "Rosie the Riveter" had been in there, because we

would find hairpins in the structure of the airplane. That was a lot of fun. It was pioneering work.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was that done to check quality control?

Charles Gray Strum:

It was a stress test. For example, we would test an airplane that had made a hard landing to see if the wings had been over-stressed. We would wrap x-ray film around the fuselage, put our camera in the middle, and start taking pictures. That was a lot of fun, and, of course, being here in my hometown as a senior commanding officer was great. I had a lovely set of quarters on the station, a Filipino steward, and the whole works.

Morgan J. Barclay:

It would have been interesting being involved in all that training.

Charles Gray Strum:

Absolutely. That was for two years. Finally, all good things come to an end. They offered me a post as defense attache' in Rabat, Morocco.

I said, "Fine, that sounds interesting. We'll go over there."

This involved a one-year training time in Washington--training pipeline. They put us in a French language school to completely immerse us in the French language for three months. I went to the Defense Intelligence School for six months and then a bunch of State Department schools. At the end of the year, we went to Morocco and took up residence in Rabat.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When did you actually get there?

Charles Gray Strum:

In 1966. We were there for three years, until 1969. It was magnificent. I enjoyed it. It was different from anything that I had ever done before. We were directly involved in the intelligence process there. We were there during the Arab-Israeli Six Days' War, which was very interesting. Morocco didn't become as involved as some of the other countries.

Arabs, however, are funny people. Their mindset is different. They had to appear to be involved whether they were or not. I remember they sent a whole battalion of airborne troops and nobody heard from them or knew where they were. I got hold of the head of the Air Force and asked him what happened.

He said, "They had to land somewhere in Tripoli."

When they say Tripoli, they mean the whole North African coast. We found out what they had done. It was a token. They had sent these people off, ostensibly, to go to war, but they never got there.

During that period of the Arab-Israeli war, my defense intelligence office in Rabat reported more Soviet intelligence than any other country's in the world, which I thought was rather surprising. But it was an enjoyable tour. It was something different and we had a lot of fun. We were able to travel a lot. Happily, it was all business, but we had a lot of fun mixed in with it.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Your unit was responsible for gathering intelligence in this strategic area.

Charles Gray Strum:

That was the principal mission. There were other secondary missions, such as goodwill and support of the Sixth Fleet units. Whenever they came into the country we would set up office and look after whatever they needed as well as entertaining for them. Of course, that would be an opportunity for gathering intelligence. We would give a big party for the ships' officers and invite some people that had been targeted for finding something out from. Interestingly enough, Barbara Hutton used to give a party every time a ship came into Tangier. That was a beautiful occasion. We collected a lot of intelligence that way as well as providing support for the Sixth Fleet units. That was a lot of fun. If my wife had her way, we would still be there, I think.

Morgan J. Barclay:

She enjoyed the European influence.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes, she did.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were able to travel and to meet a lot of people.

Charles Gray Strum:

Yes, quite a few and there were a lot of visitors, too. Just like when I was in Sangley Point. We always caught all the visitors that wanted to go to Hong Kong. They had to have some reason for being there so they would inspect the Naval station at Sangley Point. Then they would go to Hong Kong or Tokyo or wherever. When they would come over and inspect the defense attache's office, they would then head for Marrakesh.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Good jumping off point.

Charles Gray Strum:

Usually I would go with them.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That was beautiful country, I imagine.

Charles Gray Strum:

Oh, lovely country. We were able to do some exploration. We went down to a city called Agadir in southern Morocco where they had a huge earthquake about eighteen or twenty years ago. It was a very disastrous earthquake. We drove back to Rabat via the Atlas Mountains. I had a native driver, an Arab. We started getting higher and higher up in the mountains and the roads started getting narrower and narrower and, finally, it got down to what we call in French piste, a trail. Finally the piste ran out! We were on our own up there at the top of the Atlas Mountains. It was a very adventurous trip. Morocco really is a beautiful, lovely country.

At one point in time, we had a lot of close dealings with the Moroccan government. Morocco was one of the first, if not the first nation, to recognize the independence of the United States. The leader of Morocco, King Hassan Deux (Hassan II), was a very nice guy.

He was young then and very worried about his neighbors, the Algerians. I ran a capability and intention study for him: Morocco vis-a-vis Algeria. He was so appreciative of this. When I left, he gave me the highest medal he could give to foreigners, which I appreciated very much. He was a fine guy. During the study, when we debriefed him, I spoke in English, because although my French is pretty good, I didn't want to have to get technical. We had an interpreter from the embassy there to interpret for him. He sat there and smiled and four or five times he corrected the interpreter. He was right! He spoke very good English.

Morgan J. Barclay:

He didn't even need the interpreter, did he?

Charles Gray Strum:

He was smart. While the interpreter was interpreting, Hassan was deciding what he was going to say next. It was a beautiful tour. We enjoyed it very much indeed.

That was my last overseas tour. From there, I became commanding officer for the Naval Reserve Training Center in Miami.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When was that?

Charles Gray Strum:

From 1969-1970. We enjoyed it very much. We had primarily surface Navy units down there, although there were a couple of aviation organizations connected with it. We occupied what used to be the Coast Guard Air Station just south of Miami. At that point in time, I started having some back problems, which finally developed into forty percent disability. They said it was time for me to quit, so I retired in September, 1970.

Morgan J. Barclay:

While you were at the Naval Reserve, was that primarily training?

Charles Gray Strum:

It was all training. We had a little mine sweeper that we trained people on. Then we ran drills and classroom training at the center. Of course, it was a public relations job as

well.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You definitely had an interesting career covering a lot of different things.

Charles Gray Strum:

When I got out I retired here in Jacksonville. I started a little business here which I ran for six years. During that time, I became very active in my church. I was the chairman of Christian education and ran a couple of their canvasses for a couple of years. I was elected to the vestry, which is the governing body, and became the senior warden of the church. At that point they said, "This church is getting big enough for a business manager. Would you do it?" So I sold my little business, went on the church staff, and I've been there the eleven years since.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You haven't retired yet, have you?

Charles Gray Strum:

No. I'm still a business administrator in the church. I work about a sixty-hour week there--not because I want to make a million--it's because I enjoy it.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I think it's great to keep goals and to keep on going. Thank you for taking the time for the interview.

[End of Interview]