| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

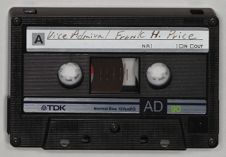

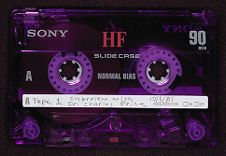

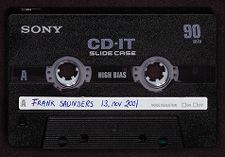

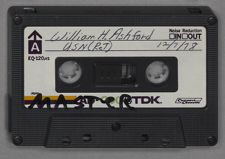

| Vice Admiral Frank H. Price, Jr. | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| February 6, 1988 | |

| Interview #1 |

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

I was born in Van Lear, Kentucky, which was a coal-mining town run by the Consolidated Coal Company. My father was the company's secretary for that particular operation. I grew up in Van Lear and went to public school there for both grade school and high school. I completed high school in 1936. That was essentially in the middle of the Depression and it was difficult to go to school. My uncle was head of all the Inland steel mining operations, also in eastern Kentucky. He had considerable political clout, being in that position. His brother-in-law was a captain in the Navy at that time, having gone through Annapolis, and he suggested that quite possibly I would like to go to Annapolis. He was able to get me a primary appointment, but being from a small high school in Kentucky I could not qualify for the Naval Academy; therefore, I went to Columbia Preparatory School in Washington for a year, from 1936 to 1937. I took those courses that I had no background in. For example, I had had no physics. I had had very little of the background material that I needed to take the entrance examinations. After preparatory school, I passed the examinations in 1937 and was due to enter the Naval Academy in June of that year. But when I went to Annapolis to enter, I failed the physical examination on my eyes. That was the first year that they had ever refracted eyes for the physical examination.

They said I had a quarter of a diopter myopia, but I went to an ophthalmologist after that and he said it was so small that he wouldn't even consider it.

In August, they had so few people getting into the Class of 1941 that they called those back who had very small things wrong with them for a reexamination. I passed that and entered the Naval Academy in August 1937. I actually entered on Friday the thirteenth. I had considerable trouble in academics in the first year or two, I finally got squared away and graduated on February 7, 1941, with the rest of the class. I was commissioned that year.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about some of your recollections of the Naval Academy as far as the quality of instruction.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

The Naval Academy, in those days, was not like any college or university really. A lot of the professors were naval officers. The head of the department usually set up the curriculum for the particular course, and the naval officers were more like referees between the book and the written material and the student. They didn't teach very much, except in courses like ordnance gunnery, navigation, or seamanship. Of course, they were well qualified for those. But when it came to English, mathematics, physics, or chemistry, you pretty well had to dig it out of the book yourself. Learning to do this was a thing that took me about a year or so. I failed Spanish the first year and had to go before the academic board. They gave me a re-exam and I passed that. Finally, I got squared away. (Like all other things, when they finally assigned me to overseas duty, I went to Spain.) In any event, I enjoyed the Naval Academy. It was hard work for me, but it was fun.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were active in the Trident Society, I believe. Wasn't that the literary society?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes, it was the literary society. I didn't do any athletics because it took me too much time to get through the academics. The first year, I think, I stood seven hundred and

something, and the last year, I stood nineteen.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you think your background of being from a small school probably was a factor in your problems early on?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

It hurt very much because there were people in my class who had had a year or two of college, who had gone to large schools, and so forth. It made a big difference the first couple of years. After that, when I got into more naval subjects, why then, it was pretty much equal and I could go ahead. I did have problems early on because of my background. We had good schools in Kentucky but they were very limited in what they taught.

Donald R. Lennon:

In the days before consolidation, the small schools just couldn't offer as much.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

That's right. We had twenty-three in my high school class.

Donald R. Lennon:

I had twenty-six in mine, so I know where you're coming from.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

I think that's enough on my background in the Naval Academy. The first assignment was to the USS WALKE a destroyer, DD 416. A number of us reported to Charleston and took the POTOKA(?), an oilier which used to have a dirigible mast for the AKRON- and MACON-type dirigibles. We took that down to the Caribbean and I joined my ship down at Fajardo Roads.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were one of those few who weren't sent immediately to Pearl for your first assignment.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

That's right. A few of us were lucky enough to get destroyers. They normally, prior to our class, did not immediately assign graduates of the Naval Academy to destroyers. They had to go to a cruiser or battleship first and become qualified watch officers. Due to the war coming on, however, some of us were lucky enough to get assigned to destroyers

right after graduation. That was the reason I didn't go to the Pacific. There were no battleships really in the Atlantic at that time except the old training squadron. They were all in the Pacific.

I went to join my ship down in Puerto Rico and operated down there for several months. Ernie King happened to be the head of the group that I operated under. At that particular time, he was very interested in camouflage. I think we painted the ship different colors once a week and steamed by to let him see which colors were best for the camouflage-type operations.

Our ship then went to Charleston Navy Yard. We were there for a month getting some twenty-millimeters and other things put on the ship. Then we were assigned and home-ported out in Newport, Rhode Island. We started running the old "Neutrality Patrols" where we would supposedly go out to a place in the Atlantic and steam around for a while and then come back. That lasted for a short period of time and then we got involved escorting convoys to within five hundred miles of England where the English would pick them up. We did the whole North Atlantic during that period of time. We also escorted the first group, the Army troops, to Iceland when we established a base there. I can remember one day, we left Reykjavik to go out to see if there were any survivors from a convoy that had been badly mauled by the Germans. Before we could get back, one of the big North Atlantic storms came up. We headed into it at about seven knots and we wound up about a week later having been blown all the way to the Faeroes, north of England. That was the kind of weather we had to operate in.

I remember on December 7, we were steaming singly--I can't remember the exact reason that we were not with anybody--from Argentia to Reykjavik, when the word came

that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. I had the deck at that point. Four hours later, we had orders to turn around and go to Norfolk, which we did. While we were in Norfolk, they put radars on the ship. They thought I had appendicitis so I was transferred to a hospital there for a couple of weeks. Because of this, I missed the sailing of the WALKE which was going to the Pacific. LantDiv 3 was over here at that time and they sailed those three battleships around independently in different groups. The ship I was in, the WALKE, took one of the ships around, and I was put on another ship from the same division, the O'BRIEN DD 415. We took the IDAHO around about a month later to the Pacific, to Pearl Harbor. I was on the O'BRIEN with orders to be transferred to the WALKE when we met, but we never met, so my assignment to the O'BRIEN was made permanent. We escorted carriers in the Pacific. At one time, we were at sea 101 days without the engines stopping. In those days, that was a long time because the ships were small and we didn't have the capacity for carrying food. We also operated for a period of time independently down in Samoa, escorting Marines around to the various islands in the region.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were out in convoy for long periods of time, escorting carriers, did they transfer food and provisions from the merchant ships?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

They would share a little bit. One of the big times was just before we were going to invade Guadalcanal. We took one carrier group back to Pearl, orbited off the the harbor entrance, picked up the next one coming out, and took it back to the Pacific without ever going into port at all. During that time, the tanker's supply officers would go into Noumea, or some of the islands down there, and pick up all the fresh fruit and vegetables and things they could get their hands on. They would come out and transfer to each destroyer what

little bit they had--your share of it. The carriers would occasionally send us over some bread and things like that. It was a very tough time at that point down there. We didn't have many ships.

Donald R. Lennon:

I've heard that on some battleships, such as the NORTH CAROLINA, they would send ice cream over to the destroyers.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

That's right. We'd get that if we were lucky enough to go alongside for fuel or something.

During the invasion of Guadalcanal, the HORNET and the WASP operated together. We had taken the original landing force in and had supported it by sending planes in. On the same day, the WASP, the O'BRIEN, and the NORTH CAROLINA were all torpedoed. We got hit in the bow and the force of the torpedo broke our back in the engine room. We did not sink, however, at that point. We went into Espiritu Santo for a day or two and then went to Noumea. In Noumea, they didn't have a dry dock, so there was no way they could repair the ship. They did a little work on it, but as I found out later, they didn't do anything to really strengthen the ship's hull girder.

Donald R. Lennon:

How could you stay afloat?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

We could stop the water from coming into the bow where we were hit. The force of the torpedo on the bow, however, pulled the bow up so it was not supported in the middle and it wrinkled the hull. All the deep longitudinals in the keel were all wrinkled. It didn't cause a rupture at that point, but there was no strength in the hull girder. Finally, they put a few patches on the wrinkled spots and said, "You can try to get back to Pearl." We started off to Pearl but we broke in two and sank off of Samoa.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who did you have with you?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Nobody. We were alone. We had had a little trouble with the bow, so we went into Suva, in the Fijis, and poured the bow full of concrete in order that it wouldn't give us any trouble. We then started out to Pearl. We broke in two about three o'clock in the morning five hundred miles north of Samoa. Fortunately, when we sent out an S.O.S. that we were sinking, one of our tankers was heading back to San Francisco. He was about thirty or forty miles away. The ship sank. The tanker got there about daylight and we had already abandoned ship. It's lucky he came, because the crew was scattered. We couldn't keep everyone together. We were scattered all over the ocean. But we didn't lose anybody.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's amazing. It looks like, knowing the condition that the ship was in, they would have sent an escort with it.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

They didn't have any extra ships.

Donald R. Lennon:

They just didn't have the ships to spare.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

We were lucky. I was a communications officer and was also officer of the deck when we broke in two. The captain said he wanted to save all the registered publications. So when the ship broke in two, I had to go down and try to get all the publications.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the seas rough?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

No, there were just the normal swells that you get in the Pacific. It was just the constant working that broke it up. That tanker that picked us up was the CIMARRON. She carried us on to San Francisco where we stayed until they gave us orders to new duty stations. It was one of the few times after a ship was sunk that they gave us a choice of where we wanted to go. Usually, they just assigned you someplace. I had had enough of the Pacific and my best girl was on the Atlantic side (in Kentucky), so I decided that I

wanted to go back to the Atlantic. I was lucky, and was assigned back to the Atlantic.

We were torpedoed in August of 1942; the ship finally sank on October 19; and we arrived back in San Francisco on November 1. I received orders to a new destroyer being built in Portsmouth, Virginia. I had a month's leave and then went to the Naval Gun Factory in Washington for a course in gunnery. I reported to Norfolk in January and commissioned the USS SHUBRICK DD 639. We operated in the Atlantic, escorting convoys to Europe. We took part in the invasion of Sicily. We were one of the fire-support ships at Gela. We had an interesting experience there. The German tanks were coming down and attacking Gela, just about pushing Patton off the beach. We happened to be the fire-support ship that day for that area. We set the course and speed for the road they were coming down. We had a spotter, and we turned a whole batch of tanks around and kept them from being pushed off the beach. The ship behind us, I can't remember the name, in column as we were going into Sicily, was attacked by German bombers. They got a direct hit and just disappeared. They were about a thousand yards astern of us. It was one of our destroyers and it just vanished.

We went from there to Palermo and supported the Army there. After they took Palermo, we operated in and out of the harbor there. We would go up the coast and try to shoot the German "Rhino-ferries"(?) that were carrying the troops back over to Italy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Softening up the land batteries?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes, and also trying to sink the German small craft that were taking their troops ashore.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many ships did you have operating with you?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Well, we had two cruisers and two squadrons of destroyers that were operating at that

time in and out of the northern coast of Sicily.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did the German Navy have in that area?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

They didn't have any ships at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not even any submarines?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

They probably had a few submarines but they didn't do anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

It looks like that would have been ideal use for their submarines.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

I don't know why they didn't. There were no submarines when we landed the three groups in Sicily. The main things were air raids. We had air raids almost every day. We were in the harbor in Palermo one night and an air raid came over. All the ships were getting underway. As we were clearing the harbor, we were bombed. We took a thousand-pound armor-piercing bomb right down between the stacks. Being an armor-piercing bomb, it went through and blew up underneath the ship like a mine, almost. We didn't sink, but it flooded the two middle engineering spaces, the after fire room, and the forward engine room. We stayed in Palermo, off-loading torpedo tubes and everything, because we didn't have much stability with those two spaces flooded. We lost about thirty people in that particular bombing. People were parboiled in the engine room. The bomb went through two boilers and the superheated steam and everything else killed them. We were in Palermo for about a week. While we were there we took a couple of houses in the city and moved the crew up there at night, and worked on the ship in the daytime. Finally, we were towed to Malta.

Donald R. Lennon:

You really didn't have facilities there for doing major repairs did you?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

No. They had none. All the shipyards in Palermo had been bombed almost out of existence. They sent a Navy tug up and it towed us to Malta. The MAYRANT, which had

also been bombed in Palermo, had been towed to Malta, too. We were put in dry dock there, but the blitz was still on. The German air raids would come over and everybody would just abandon ship. We would go over in the caves that had been dug in the sides of the rock there until the bombing was over. Then we would go back and work some more. The Maltese dock workers struck because they thought they weren't getting enough food and everything, so we had to do our own work. I learned a lot while I was in Malta, because there was a major British constructor there who had built the KING GEORGE V battleships. After many nights of talking to this British constructor, I found out why the O'BRIEN had sunk. It was because they hadn't done anything to strengthen the hull. When we repaired the SHUBRICK, we cut out sections of hull about fifty feet long and put in new sections and new hull plating.

Finally, we were ready to go home. We had no evaporators, they had been damaged, so our executive officer went over to Africa and picked up an Army field evaporator. We put that on the fantail and started home. We had one shaft and all the steam lines were up over the decks and down. We were with another destroyer, about three or fours days out, heading back across the Atlantic, when we got orders to go to Casablanca so we could go back with a convoy. Our commanding officer ignored it. We kept going. We got about three messages and, finally, he sent one saying, "We are over halfway home; nothing is wrong; we are getting along fine." He wasn't going to go to Casablanca. He got by with it! We finally got into the New York shipyard. They got the ship and replaced everything.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they planning to do the repairs in Casablanca or were they just going to put you back in service with no repairs?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

They just wanted us to go back home with a convoy of twenty slow ships, which

would have put us back, God knows when! The skipper was Lou Bryan at that time, who was later made admiral. He just ignored it and kept going. He could get by with it in those days.

At that time I was gunnery officer on the SHUBRICK. While we were in the shipyard, the skipper was transferred; the executive became the commanding officer; and I fleeted up to the executive officer position. We left the shipyard in the early spring of 1944. We spent that spring taking fast convoys over to England for the build-up of the Normandy Invasion. Along the latter part of May, we operated out of the ports in England and spent quite a bit of time at Eisenhower's headquarters, getting briefed for the invasion. We went to Belfast and were sealed--nobody could leave the ship. We got our instructions, read them, and took off for the invasion.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long before D-day were you really informed as to what was going on?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

We were not informed as to where we were going to land. We were not informed as to the specific details, but we were paired off with the Army unit that we were going to support. We shot for them and they controlled our fire down at Shepton Sands. If you remember, just recently there was a monument erected there, because in one of the Shepton Sands operations, German E-boats got into the middle and sank and killed a large number of Army troops. The day before that we had been down there shooting. The next day, this group went there to practice their landings, and they didn't have any destroyers with them or anything. That's the one the German E-boats got into the middle of.

We did not learn the specifics of the invasion until we were sealed. Every ship went to a port. At that point, they "so-called" sealed the ship. Nobody could go ashore except the captain and the executive for the meetings and what not. Everybody else couldn't leave the

ship. Nobody could come aboard. When we opened all the orders, that's when we learned the sites of the landing, and the beaches, and all of the details.

We were the first ship, destroyer, in Normandy from the American side. We had a fire-support position which was right where Omaha and Utah beaches joined. The mine sweepers had been in but we were the first combatant ship to go in. We started the softening-up fire-support for the Army. We shot up all of our ammunition in the first four hours, I guess. By 10:00 that morning, we had shot everything that we had. We were ordered back to get another load of ammunition. The ship that relieved us was the CORRY. We went back across the channel and went in and picked up our load. There were barges specifically labeled for each ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had to go all the way back to England for reloading?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm surprised that they didn't have ammunition ships.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

There was such a mass of ships that they couldn't. Many of the ships had different batteries and different types of ammunition.

Donald R. Lennon:

It isn't far across the channel, anyway.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

It's only thirty miles. Each ship was assigned a specific port where it would find a barge labeled for it with one complete load of ammunition. Ours was in some small port, although I have forgotten the name of it right now. We reloaded and went back. When we got back, the ship that had relieved us was sitting on the bottom with just the top of her mast sticking out. She had gotten caught by shore batteries and sunk. We operated around the invasion beaches in Normandy for about a month.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't take a hit at all during that time.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

No. We anchored at night as a perimeter around the U.S. landing area to protect against E-boats coming out of Cherbourg. We had several fights with the E-boats coming down. One ship, the flagship of our division, had an E-boat torpedo blow its stern off. We were lucky. We didn't get anything there.

I well never forget the day they called our skipper over on the flagship and told him to take his ship down off the coast of Cherbourg to check on some shore batteries. About three days before, two battleships, some cruisers, and some destroyers had gone up to Cherbourg and gotten several hits from some shore batteries that we had been told the Army had already taken. We were told to go up by ourselves and verify that this was true. We went up merrily along the coast there and when we got near Cherbourg, we were straddled by a couple of eleven-inch shore batteries. We ran like heck and they didn't hit us! We came back and said, "No, the Army hasn't gotten all those positions yet!" They were too far out of our range to shoot back. All we could do was run.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was trying to remember when the 79th Infantry Division went ashore to Cherbourg. I don't remember exactly when they got in there. I know it was more difficult taking Cherbourg than they anticipated.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

It took them about a month or pretty close. Funny things happened then. One day we were patrolling, waiting for the Army to call for some fire, and about four or five "ducks" came over. They had come all the way from England. They were filled with construction troops and carrying landing mats to form a light airstrip over there for Army observation planes. They came alongside. An Army captain was in command and he said they were supposed to go to a specific spot and build this airstrip. He wanted to know where was it from where we were? They had no navigation or anything else. How they ever got there, I

don't know.

We said, "You can't go over there. The Germans are still over there."

Well, he said, "That's where we're supposed to go." So they chugged off into the beach. They got pretty close to the beach when the Germans started shooting at them. They came back out, fast! It was an all-black unit. There were some real scared people in that organization. They finally took our advice and went down to another spot where we knew we had the beach. There were a lot of funny things like that that happened there.

Yes. We told them they had better not go there, but in they went! Those were hard times. I didn't go to bed for a week. We'd take pills to stay awake because something was happening all the time.

Donald R. Lennon:

How great was the problem from German aircraft?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Very little. We had very little German aircraft. We had such air superiority over the beach areas that it wasn't a threat. We had very few attacks. The main things they had were guided bombs. They would come fairly close to the area and launch those bombs and radio-control them to try to hit a ship. As far as I know, they never hit anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

The greatest danger came from the mines, the E-boats, and shore batteries?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Right. We left Normandy and were ordered down to Naples for the invasion of Southern France. We were in Naples for a couple of weeks and then escorted one of the light carriers that were furnishing air support for Southern France. After that, we came back to the States.

About that time, I was relieved. This was in August 1944. In October 1944 I went to the U.S. Naval Post Graduate School. It was in Annapolis in those days. I reported for an ordnance engineering course. I had been promoted to lieutenant commander during that

period of time on the SHUBRICK. I stayed two years in the post graduate school. In March of 1946, I was ordered to the USS MISSOURI where I was the assistant gunnery officer and air defense officer for three years. During that time, we made trips to the Mediterranean and also operated out of Maine for a summer. We normally should have had twenty-two- hundred people on the MISSOURI for a full crew, but starting that summer, we operated with about twelve-hundred for about a year or two. It was mainly training--going over with the Sixth Fleet, occasionally operating in the Caribbean.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was nothing much happening in the Mediterranean at that time.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

No. Mainly, we had people from other countries come aboard and tour and things of that nature.

Donald R. Lennon:

Diplomatic relations.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes. Nothing much happened. In August of 1949, I was transferred to the Bureau of Ordnance. In 1949, I made commander. I went to the Bureau of Ordnance and was in the research and development division. I had two sections, RE-3f and RE-3c, which were armor, rockets, bombs, projectiles, and guided missile warheads--the research and development for those types of ordnance.

In September of 1951, I was ordered to command the USS BEALE, DDE 471. They were twenty-one-hundred-ton destroyers that had been put out of commission, reactivated, and were being equipped with all the latest anti-submarine equipment: fire-control, underwater fire-control, torpedoes, weapon-A rockets, and things of this nature. I went to a shipyard in Boston to commission the ship in November of 1951. We became part of Escort Destroyer Division 22. Our primary job was anti-submarine warfare. We operated in the Mediterranean. We also went up to Ireland and operated with the British out

of Londonderry, Northern Ireland. At one time, I had the plane-guard duty in Pensacola for the training carrier. We operated in the Caribbean. It was this type of operation.

Finally, we took the ship to New York for an overhaul, where I was detached. I was ordered to the Naval Gun Factory in Washington and reported there in December 1953. At first, I was the inspection officer for all the things we built. Later on, I was made the comptroller and we installed the Naval Industrial Fund accounting system. We got that going and later on I was transferred to the planning division. That was a busy number of years. I had never even balanced my checkbook. My wife did that. We got the accounting system going and it finally worked, but it was a problem. I left the Naval gun factory in June 1956 and went to the National War College in Washington to take the senior course there. I was still a commander and, at that time, I was the youngest Naval person to go through the National War College. It was a very interesting tour of duty and one vastly different from anything I had done. It really isn't a war college, it was a foreign affairs college. We studied the economics of and the diplomacy associated with foreign policy. That was a very interesting tour.

I was detached from that in August 1957 and was ordered to Spain. I had duty as the deputy chief of the Navy, section MAAG. That's the Military Assistance Advisory Group. I spent two years in Madrid, Spain. That was most interesting.

Donald R. Lennon:

What exactly were you doing?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Our duty primarily was to interface with the Spanish Navy in building up their abilities. It all came under the military assistance program to Spain. In 1954, we established a treaty with Spain that gave us the right to build our bases there. Rota was the Naval base. Moron near Sevilla, Perhom(?) near Madrid, and Saragossa north of Madrid

were all air bases. The U.S. had to build the bases. In payment for the use of these bases, there were moneys and equipment and whatnot set aside for the Spanish Navy, Army, and Air Force. The MAAG had the responsibility for building the program for their particular Spanish compatriot service and administering the equipment arrivals, the shipbuilding program, and all of that sort of duty. At that time, we came under the U.S. UCOM(?) headquarters in Paris. We had to spend about one week out of every five working up in Paris.

We lived on the Spanish economy. I had two children and they enjoyed it. Everyone was fluent in Spanish. The Navy sent both my wife and me to language school in Washington, a private school, for two months prior to going over there. We were fairly well versed. I had had Spanish in the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was going to say, that's a far cry from your first year at the Naval Academy.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes. It was very interesting and we made a lot of friends in Spain that we still have. We traveled through Europe and through Spain, thoroughly, during that period of time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you miss sea duty at that time?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

No, because there was so much going on. It was just so interesting that I didn't really miss anything. It was something so new and different and very, very interesting. They Navy used to treat its people very well. We went over on the CONSTITUTION, which used to be the old American Export Line, and our car was right on our ship with us. It was off-loaded in Algeciras. When we went home, my wife took the car back. The head of the American Export Line was a retired Navy admiral, Admiral Will, and he met my wife on the ship. When the ship pulled in, just on his own hook, he had gotten our car out of customs in Bayonne and brought it over and had it sitting on the dock for her. We don't do

that anymore! It was nice in those days.

I made captain during the tour in Spain, and when I left I was assigned to commander of Destroyer Division 362 out of Norfolk. The flagship was the USS WILSON. I only had a year in that tour. We operated as a division primarily out of Norfolk on operations around the Caribbean--training operations, ASW exercises, things of that nature.

In October of 1961, I was assigned to chief-of-staff of ComCarDiv 18. That was an ASW carrier division on the old ESSEX. We were based out of Quonset Point, Rhode Island, right across from Newport. We did a lot of interesting operations. We went through the Suez Canal and operated with the Pakistan Navy in the Indian Ocean. In those days, we operated around the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea. We operated with the British off of Iceland, England, and Ireland.

Donald R. Lennon:

Purely training maneuvers?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

All were ASW training exercises. That was my first tour of duty on a staff. I had never had any staff duty, so it was interesting from that point of view. Then in 1961, I was assigned to ComOpTevFor in Norfolk and I was head of the undersea warfare test and evaluation group. We tested all the new anti-submarine weapons: torpedoes, rockets, aircraft, everything that had to do with ASW undersea warfare. Everything had to be tested by the operational test and evaluational force before it was approved for use in the Fleet. I was there for a year and was looking forward to having another year or two when in the spring of 1962, I was called up to be interviewed by Rickover in Washington. I told them I didn't want to go over to the nuclear power business.

They said, "Well, that's fine. We have somebody picked but he has to look at more than one."

I was interviewed and frankly told him I didn't want the job.

He said, "Well, there's no use in interviewing you."

I said, "Well, that's up to you."

Donald R. Lennon:

I understand he was rather blunt.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes, he was.

Finally, he said, "Well, if you're chosen, will you take it?"

I said, "Yes. Whatever the Navy tells me to do, I do."

So I was the one selected to be the commanding officer of the LONG BEACH, our first nuclear-powered surface ship. I spent a year, 1962 to 1963, undergoing nuclear power training.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why were you not particularly interested in it?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Well, it had been a lot of years since I had done any technical educational work. I had become very, very interested in anti-submarine warfare and I had probably one of the best jobs for that in the Navy down in OpTevFor. I had just bought a house in Norfolk and we hadn't moved in it yet. I had to sell that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was the LONG BEACH headquartered?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

She had just been commissioned the year before. Her big radars were being installed in Philadelphia. She had made one trip over to Europe for a month or two, it was the only time she had been at sea. Captain Wilkinson, who was a physics professor and had become a Naval officer, was the one who had spent the two years that she was being built, getting the nuclear power installed. I didn't go to any school. I did all my training in Rickover's office. All his department heads were the teachers who gave me the courses.

Donald R. Lennon:

Almost one on one.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

It was. I did have to go out to Idaho and go through the prototype training in Idaho. Finally, I finished that in June of 1963. I then went over to Naples. The ship had just gone from the States to Naples, and I took command of it in Naples in 1963. I had command of her for three years. I was relieved on 1 September 1966.

Donald R. Lennon:

After you got involved in the nuclear ships, how did the LONG BEACH handle differently from the conventional ship?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

The LONG BEACH is a very interesting ship. Those three years were real busy ones. We did two tours of duty in the Mediterranean. Then we made port of calls all the way from Turkey to Greece to you name it--all over the Mediterranean.

Donald R. Lennon:

That wasn't a period of crisis in the Mediterranean?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

No, it wasn't at that point. We had the Sixth Fleet homeported in Villefranche. This was before De Gaulle kicked them out. From there, of course, they went over to Italy. We also made the around-the-world cruise with Joint Task Force 1. The ENTERPRISE, BAINBRIDGE, and the LONG BEACH were the three nuclear-powered surface ships in the Navy. We went over to the Mediterranean, left the Mediterranean, went down around Africa and the Cape of Good Hope and then up to Karachi for one day. We went around to Australia, where we spent two days in Melbourne, and then a day and a half in Wellington, New Zealand. We went from Wellington around Cape Horn to Rio de Janeiro and then back home. We didn't replenish anything--no fuel, no food, or anything. I think it took us fifty-four days. That was very interesting to do at that point.

When we got back, we went into the Newport News Shipyard and refueled. It was the first refueling of the core and two reactors. How were they different? They were

different in several ways. It was a full missile ship. We had Terrier missiles, four directors, two launchers, forward; and we had long-range Talos missiles, aft. We had the big radars. We could automatically track several hundred targets at one time. It was a forerunner to the AEGIS(?) cruisers that we have today. The radars were the same types except they were not nearly as sophisticated as those now, because she was built in 1960 and commissioned the first time in 1962. You can figure that her radars were whatever radars they had five years before that. But at that time, she was the best they had. The differences: We never had to worry about fuel; and we could get under way quickly as long as the reactors were critical, we didn't have to warm up boilers or anything. It was, however, a very complex plant and we had to have people who knew what they were doing in running it. For example, we had to undergo a nuclear power inspection by Rickover's group, which was a very harrowing experience to go through, especially after having just refueled the ship. About every six months, we had to start training again because although the reactors worked well, the people did not always remember. In the day after day of normal procedural things, they would forget the emergency procedures and everything else. We immediately had to start retraining. I think I trained three complete crews in three years. It was very difficult to keep the proficiency up.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you ever have an emergency of any kind?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Oh, your plant would "scram" occasionally, but it was always that somebody had made a mistake, but there was never a crisis. The first core lasted about four years; the one we refueled was going to last seven years; and now they last about fifteen. That is one of the improvements--being able to pack more uranium in the core and still have it controllable.

At the end of that tour, the ship was moved to the Pacific, so I took the LONG BEACH to Long Beach and that was nice. I had six months there before I was ordered back to Washington. That whole period of time was filled with all sorts of events. The skipper I had back during the war, when I moved to executive officer of that destroyer, had made flag rank. He had his flag on the LONG BEACH and I was his flag skipper. His name was Admiral Smith. It was almost three years to the day that I left the LONG BEACH and went to the Bureau of Naval Ordnance in the Surface Missile System Project. While I was there, I was still a captain, but I fleeted up to the head of the Surface Missile System Project. We did all the standard missiles, all the Navy surface-to-air missiles--developed them, bought them, installed them, and so forth.

While I was there, I was promoted to rear admiral and was immediately sent to head Cruiser Destroyer Flotilla 8. It was based down at Norfolk. We went to the Mediterranean and I had one of the good experiences of being one of the few non-aviators who commanded the Carrier Task Group 60.2 on the Mediterranean. There are two task groups in the Sixth Fleet. Each one has a carrier and I happened to have one of them. We had a lot of fun there. We did have a crisis one time when a TWA airliner was hijacked and landed in the middle of the desert in Jordan. We were sent over off of Cyprus to orbit in case we had to do something. We didn't have to, but we went silent on everything and dodged the whole Russian Navy and Air Force for four, five, or six days until we got where we were going. They didn't know where we were. It was fun.

Donald R. Lennon:

You played cat and mouse.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes. We did things like that. I was detached from CruDesFlot 8 in 1970 and went back as deputy chief of the Naval Ordnance Systems Command. I was there for a very short

time and then had orders to the Pentagon as head of the ship's Characteristic Board. While I was there, they combined all the shipbuilding under one office. I became the deputy CNO for shipbuilding and was promoted to vice admiral. We had the responsibility for getting the money to build the ships, getting the ship's characteristics out, and making sure that they were built the way they were supposed to be. After about two years, I guess, I was then made deputy chief of naval operations for surface warfare and the shipbuilding was incorporated under that group. I just took the one and moved in.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had oversight over all types of naval shipbuilding?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

The DCNO Surface Warfare had the responsibility of developing the programs for shipbuilding. The program also included building submarines and was involved with developing the budgets and getting it through Congress. I also had the responsibility for all the Navy weapons and getting those programs through Congress.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had a lot of public relations work to do on the hill.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

I spent a tremendous amount of time on the hill, trying to get all the budgets and ships approved through the House and Senate, and the Appropriations and Armed Services committees and so forth. I also had responsibility for the training on all the surface ships. We established a Surface Force Pacific and Atlantic who came under OpO3 and the Mine Force came under OpO3. We were also the Marine liaison with the Navy for weapons and all that sort of thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

The nature of potential warfare had changed so much by the mid seventies. What were you concentrating on as far as the types of ships that the Navy was needing at that time?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Admiral Zumwalt was the CNO during the large part of my tour in the Pentagon, and

he was trying to build the Navy back up. Our ship numbers had sunk after the Vietnam era, and the ones we had were old and needed to be replaced. We didn't have a whole lot of shipbuilding money; however, so we were concentrating on building up our escort forces, the FFG-7 class, starting with the AEGIS(?) cruisers. We built a number of nuclear-powered cruisers, the CALIFORNIA, the TEXAS, and others, and nuclear-powered carriers. We got the high class FBM submarine program started, and the 688 class of TAC(?) submarine program started. We also built the hydrofoils, the ones that are now based down in Key West. We wanted to get mine-sweepers started. We had a new class of oilers, but the problems that we ran into were that the aviators and submariners all wanted the expensive nuclear-powered ships. We were trying to get the surface Navy built back up and, frankly, a lot of things just couldn't be funded. Mine sweepers were one. We tried to get those; we knew we needed them; but they were not very glamorous. Unfortunately, it's a very important program.

Donald R. Lennon:

Whose decision was it to bring the NEW JERSEY out of mothballs?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

That had been talked about for years and years. The NEW JERSEY, you remember, had been brought back into the active fleet during the time of Vietnam. Then she had gone out again. It was about the time of Tom Hayward's tour as CNO that the problem was recognized of having enough flagships, capital ships, to build what we now call battle groups, (we used to call them task groups), to be in all the places in the world where we were needed. We also had developed the cruise missiles and needed ships for them. Here were these well-preserved good hulls with a lot of protection and we could take off some of the five-inch secondary battery and put on the Tomahawk cruise missiles. They would still have the big guns if you had to use them. In third world places, where you wouldn't have to

go in, the guns were pretty good. You still might not have enough carriers around to provide all the force projection with bombing and so forth. Anyway, the decision was made to bring those four battleships back, the IOWA class, and to modify them to carry the Tomahawk missiles. This decision was made after I left, but the idea was started while I was still there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you use them primarily as missile ships?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes, but you could still use them for their sixteen-inch guns. We still had a large quantity of sixteen-inch ammunition available. The gunnery systems were still good. They could support Marines. The Marines always wanted the big guns for support of Marines ashore. It was a reasonable thing. They now have a battle group. I think the MISSOURI and some cruisers and destroyers have been out in the Indian Ocean supporting the operations in the Persian Gulf. Once you have cruise missiles that can go fifteen hundred miles and hit things, you don't have to have aircraft carriers all the time. Now, instead of having crews of twenty-two hundred, I think they have about fourteen hundred. They were able to reduce the weapons, and correspondingly, the number of people on board. That was the primary reason.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were so well constructed and well designed to begin with.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes. When I was in the MISSOURI, if we opened fire at another ship sixteen or seventeen miles away and didn't get a straddle on the second salvo, something was wrong. They were beautiful ships as far as the accuracy of gunfire was concerned.

Anyway, after four years in the Pentagon, getting up at six o'clock and getting home at ten or eleven, I asked if I would be able to go to sea again. They said that I was too old.

It was for younger people. At that point, I suggested that they get a relief. They hadn't planned to relieve me for another year, but after four or five years of fighting that "hill" battle everyday, I was ready to leave.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's like combat duty.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes. Somebody else could come in and do it for awhile before I blew up someday over there. I lost a lot of respect for Congress during that period of duty. I retired on September 1, 1975, and went to work with the Sperry Corporation.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were you doing for Sperry?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Primarily, running design-systems analysis work. I didn't want to be involved in selling anything. Sperry had practically no ideas of how they could put together large systems and sell them. It took a lot of analysis work and study about what should be done. I did that for seven years. Then I quit that and I've done consulting since for various people. Now, I've almost cut that out. I now enjoy being retired.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were with Zumwalt for some period of time in the Pentagon. What are your observations about him?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Of all the CNOs I've known, Bud probably had the best understanding and knowledge of the strategic problems of the Navy and how it would meet whatever it had to meet in the future. He was the one who started the high/low-mix concept that had a certain number of very capable ships--nuclear carriers, submarines, cruisers, and so forth. There were a lot of tasks that ships not so capable could do perfectly well, and they would be cheap enough so you could get them in large enough number to do something with. I still think that he probably had the best concept of what the Navy should be and the types of ships needed. He won some battles and he lost some battles in that regard. Unfortunately,

he was C and O during a period of time when this country was completely at odds with itself. The Vietnam War had come to an end; colleges were throwing out the NROTC units; there was the black rebellion in the cities; and everything else.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was a period of anti-military sentiment.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

It was very bad. Some of the things he did probably had to be done because of the period in time, but they grated on a lot of Navy old-timers. Unfortunately, he did some things which I think were counter-productive to the morale of the Navy overall. A lot of the "Z-grams"(?) didn't make sense to me and didn't to a lot of people. For instance, having people on ships that the enlisted people could go to outside of the normal chain of command was just not good. Most people, if they can't get things done through the normal chain, tend to try to bypass that chain. An example is Reagan with the Iran-Contra affair.

Donald R. Lennon:

That undermines the entire system.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

What happened was that Zumwalt really had a small group around him. outside of his regular staff. They were in the staff but, unfortunately, they tilted a lot of things. More thought should have been given by the senior people as to what should have happened and what should have been done. A lot of the things he did for the blacks, the racial problems, sometimes I thought were not well thought out. However, a lot of his ideas that were supposedly so bad, were bad simply because the senior people in the Navy didn't support them. If they had supported them whole-heartedly, a lot of them would not have been as bad. But when they didn't like it, they would say, "Well, that's his," and sit back and do nothing. A lot of the stuff became critical that would not have become critical had the old line of the Navy supported him. He was a misunderstood person. He was a very capable officer and knew the strategic situation in the Navy better than a lot of people that followed

him. It was a bad time to start with. I personally had a lot of respect for him.

Donald R. Lennon:

I suppose that period in the seventies was the most difficult for the military community in general, with the adverse reaction to Vietnam plus all the other ingredients.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Including the all-volunteer military service. There was also a lot of conflict in that time between the Navy secretary's office and the CNO's office. Sometimes, Zumwalt had to do things that he would not have done because of the problems with the secretary.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were in the LONG BEACH, how much contact did you have with Rickover?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Well, that depended. Anything that had to do with the main propulsion plant had to go through him. If we had any incident, such as if our plant scrammed for some reason or if we got some contamination in the primary or secondary system with chlorides--things of that nature--we had to go through him. We would get some very perturbative(?) phone calls sometimes about what had happened. When we were in a shipyard, it was very, very difficult because he ran the shipyards, as far as the nuclear business was concerned. Nothing could be done there that he didn't have his people all around. He knew everything that was going on. When we refueled, it was a very difficult time. I had my engineering people on four sections: Three sections would be on duty while one section would have a week off. Those that were on reported in an hour before their shift changed to find out the state of the plant, because you had the reactor open and all sorts of things. Then they did their eight hours of duty, then another hour of shift change for the on-coming group, and then they had to go for three to four hours of school. After all this, they could go home. It was a real difficult time. Some of these people were working sixteen to twenty hours a day. It was a problem. I would get home maybe at 11:00, get some supper, and go on to bed;

and then I'd get a call from Rickover in the middle of the night!

Donald R. Lennon:

He's always been such a controversial figure and one that caused a reaction from most people that had to deal with him. Was he as cantankerous as his reputation seemed to imply?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

He was very autocratic. He was also, I think, very egocentric. He did a tremendous amount for the Navy, no question about it. I think we would have had nuclear power, but it would have been long afterwards. However, had he quit when he was ahead, it would have been better, I think. He hung on too long and he didn't allow anyone to be trained to replace him. I sat in on conversations where he tried to tell the CNO what kind of ships the Navy should have, which wasn't his thing at all.

He would say, "Well, I won't let you build those ships at all if you won't go over and do this type of thing. I'll keep Congress from doing it."

A lot of things went on. I think he also got too conservative in his plant designs, so that we can't cram the horsepower in our plants that the Russians can. Maybe we wouldn't have wanted to, but there was very little work done on new concepts or new ideas. I think he did a lot of good for the Navy, but I think that toward the end, he did us a lot of harm, too.

Donald R. Lennon:

He'd have been much better off to have stepped aside and let someone younger have taken over.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

But that wasn't his nature. He wouldn't do that. That was one of the problems that existed.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did anyone get along with him?

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Yes, sure, a lot of people. He had one man toward the end, Dave Layton(?), who had been in the Navy but had gotten out. He was a lieutenant or something. He was his deputy along toward the end. I'm not so sure whether Dave wasn't running the thing at that point. Towards the end, the old gentleman was getting a little bit. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Actually, the Navy has no mandatory retirement age.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

No mandatory retirement. Actually, he was recalled. He made rear admiral and vice admiral after he had been recalled to active duty. He was more or less a supernumerary all during that latter part.

Donald R. Lennon:

So the normal rules didn't apply.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

They didn't apply to him anyway. He would just go directly to Congress. The hell with the Navy, CNO, or anything else! Many times he did that.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know that made him very popular with the CNO.

Frank H. Price, Jr.:

Well, it wasn't necessarily a thing of being popular, it was the thing of: How could you plan to run a Navy when you had that going on? It was very difficult. There were some big fights you know as to whether the high class FBMs should have twenty-four tubes or sixteen tubes and whether they should be big or small. The Navy itself wanted the smaller submarine. He pushed that other one through. Why? He wanted to build a bigger reactor, a lot more powerful reactor. He had a lot of influence. Along toward the end, it wasn't too good for the Navy.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's the way it appeared from all the press at that time.

[End of Interview]