| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

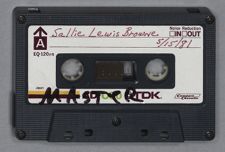

| Sallie Lewis Browne | |

| May 15, 1981 | |

| Interview #1 |

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I was born in Sussex, Virginia, January 10, 1900. My father was a minister in the Virginia Conference of the Methodist Church and we moved every four years. From 1903 to 1907, he had a mountain circuit in Flint Hill, Virginia, in Rappahannock County. We moved from Flint Hill to Scottsville, Virginia, on the James River in November 1907. We lived there until November 1911. I started school at the old Scottsville High School. It is no longer there now because it was consolidated and is now Albemarle High School. It was near my home and I could walk to school. Then my father was moved to Palmyra, which is the county seat of Fluvanna County, and I went to the Fluvanna School all through grade school up until the tenth grade. From 1915 to 1920, we lived in Stanardsville, Virginia, which is the county seat of Greene County. There was no real four-year high school in Stanardsville so I had to go live with my sister in Scottsville and graduated from high school there in June 1917. From 1917 to 1921, I was in college in Harrisonburg, Virginia, at Madison College. At that time it was a state normal college; later they diversified. I received my Bachelor of Science degree in 1921. It was while I

was there that I was introduced to the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions. Have you ever heard of that?

Donald R. Lennon:

I've heard reference to it, but I really don't know anything about it.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Student volunteers signed up to serve in countries abroad under the church. I signed up in my first year in college when I went to a student volunteer conference in Des Moines, Iowa. Then, after I finished college, I taught for three years in Woodrow Wilson High School in Portsmouth, Virginia. From Portsmouth, in 1925, I went to Scarett College in Nashville and got my masters in social science, sociology. This was in the year 1926. In that same year, I was assigned to the Jane Brown Social Evangelistic Center in Harbin, Manchuria.

Manchuria was at that time connected with China. I've forgotten who was the warlord of Manchuria at that time, but we could not go outside the city. It was dangerous for white people because they thought people with white skin were Russian and they were avowed enemies of the Russians. All the time they were watching the Russians, the Japanese were pushing in from South Manchuria.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your first reaction on arriving in Manchuria? Your background had basically been small town Virginia, and here you were in a completely different world.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Yes, well, at the time I was appointed there, there was an outbreak of a cholera epidemic in North China--Manchuria. My bishop, Bishop Ainsworth, detained me for one month in Seoul, Korea. I lived that month in the Women's Bible Training School in Seoul. Because I knew that I would need Russian in Harbin, I started taking Russian lessons from a White Russian exile living there at that time. So I knew a little Russian when I arrived there.

Donald R. Lennon:

What languages did they speak in Harbin?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

In the Chinese section, they spoke Chinese.

Donald R. Lennon:

Mandarin or what language?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Manchu, I suppose. Harbin was right at the junction of the South Manchurian Railway and the railway that connected Vladivostok. It wasn't the Russian line but the Chinese Eastern that connected Vladivostok with the Russians at the border. The TransSiberian Railway was built and operated by the Russians.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were there any Americans there other than missionaries?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

There were some in the business community and there were some British.

Donald R. Lennon:

Probably tobacconists or something like that.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I cannot remember what their work was. There was a Baptist medical missionary who had a clinic not far from our girls hostel. I used to go sometimes to the English church there. We had a church for the Russian-speaking people. They held services across the railroad tracks on the other side near Chinatown in a place called Punjidin. But we lived in the Russian part of the town where there were streets and you would see rickshaws and jirisishas . . . very few cars, but occasionally you would see a motorized vehicle. Often I would walk the distance from where the chapel was over on the China side to where I lived in the girls hostel.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this going outside the area where you were supposed to stay?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

As long as you were in the city, you were safe?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Well, not always. Sometimes even the Chinese would hold you up and rob you. But I don't know that they ever really attacked me or hurt me in any way.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did the White Russians treat you as an American missionary? Were they friendly?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Some were, but some resented us because they belong to the Eastern Orthodox church and thought we should not be there. Some were quite friendly though. My Russian teacher in Harbin, Madame Boldreaver(?), was very friendly and kind. She introduced me to some other Russians who were also friendly. Many of the Russians wanted to learn English so that they would have a better chance of passing immigration and getting naturalization papers. They wanted to come to the United States because they were afraid of the communists who were pushing further and further across Siberia.

Donald R. Lennon:

The Russians in the area at that time were not Communists at all I take it?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Yes, I think there were some. They would sometimes fight with the Chinese because the Chinese were fighting with them, too. I remember our Chinese cook came in one day from the street and said to us, “Don't go out on the street today. There is a battle in the streets, there is a war in the streets!” The Chinese and the Russians were fighting in the streets. Of course, the Chinese would take more and more advantage of being occupied.

Chung Su Lin was the warlord of Manchuria and the train he was riding on was blown up somewhere south of Mukden, between Dalian(?) and before you got to where the Chinese Eastern Railway joined.

Donald R. Lennon:

This happened while you were over there?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

It happened while I was there. The bishop immediately ordered us out and we could not get visas any other way. We finally got a visa to leave, by a German boat which sailed from Dalian(?), and we were able to get that far south.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you stay out for very long?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I was there for just one year.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you did not go back after this incident?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

No, not after that train was blown up.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any immediate reaction before you could get out?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

The Japanese were pushing in all the time. I think there were some clashes between the Japanese and the Chinese.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did the Japanese blow up the train for a specific purpose, or did they know?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

They suspected to get rid of Chung Su Lin.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned a while ago the English church. What was your relation with the Church of England missionaries? How did they feel toward you as a Methodist?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I don't remember any Church of England missionaries. It was an English-speaking church.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, I see.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

They would have services on Sunday afternoon. Sometimes the Baptists would have it and sometimes the American Lutherans.

Donald R. Lennon:

So it was basically an American church.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

That is right; with some people from England attending.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you said an English church, I envisioned the Church of England.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

So many of them wanted to learn English we had this school, a gymnasium, where they studied English as a subject. It was a Russian-speaking school but they studied English as a subject. They would have a program occasionally in English where they would ask me to speak. But I wasn't able to do very much that whole year because

Russian was not an easy language. Most of my time was spent studying the language or in the evenings I would keep study hall for the girls that would go to the gymnasium.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your primary work or responsibility while you were there? You had been sent there in what capacity?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

The Social Evangelistic Center. We were to have Bible classes and also help if we could find any orphan children. Many times there were Russian children who had been orphaned and just thrown out on the street. They had no place to go and we tried to homes for orphan children. The missionary with whom I worked was able to get one child, Vina Min Blinov, into the United States where he was able to study by using his English name, Benjamin Blina. He was put in a boys home and she helped support him. Later on he became successful as a businessman. I think the business was buying up cotton and reselling to the cotton mills.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were working as much with the Russians as the Chinese?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

More. I didn't learn any Chinese.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had you gone over there with the intention of staying a long time?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Oh, yes. We were sent for periods of five years and then allowed a furlough of one year in the United States, mainly for health reasons. This was because so often you would pick up some of those diseases like amoebic dysentery.

Donald R. Lennon:

But after the train explosion they decided to close the mission entirely?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Well, they withdrew all Americans. They were told to evacuate; their safety could not be ensured.

Donald R. Lennon:

Usually, in a situation like that, don't they just withdraw them to a neighboring area for a few months and then send them back in?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Well, when we were withdrawn, we were transferred to the White Russian work in Poland. They misunderstood; they thought the White Russians in Poland were the same as the political White Russians who were loyal to the czar in Manchuria. But they weren't, they were ethnic White Russians and spoke a dialect that was akin to Russian, sort of a mixture between Russian and Polish. Consequently, I had a very difficult time with the language.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had to learn all over again?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Some of the words, when you looked in the dictionary, would mean one thing in Polish, but in the dialect it would be different.

I was then staying in this girls home for White Russian girls in Vilnius, which is now in Lithuania, but at that time was under Poland. The Polish were not too friendly to the White Russians because the White Russians wanted to be free. They didn't want to be under Polish rule. They wanted to have their own schools. They did have a White Russian gymnasium in Vilnius, but it was hard for them to maintain it because they didn't have much money. The White Russians were very poor.

Later, I was transferred, in 1931 to Warsaw and there I had to work with Polish women. I helped them organize their Bible study groups and their groups to help one another, such as when they went to visit where people were in great poverty and hungry. I was there only one year before my furlough was due and I came home to Charlottesville, Virginia. When my furlough was up at the end of 1932, was once again assigned to Warsaw. I remained in Warsaw until my next furlough in 1938.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were in Warsaw about six years or more?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Five years counting the furlough.

While I was at home in 1938, World War II broke out and Hitler started moving his forces into Poland. I think I crossed the border just two weeks after. I would have been there except my mother was sick and I was delayed at home.

Well, after Hitler moved, I was unable to get in. So I spent the years 1939 to 1946 in the United States. In 1946, after the war and during the period when there was great devastation and relief was sent in, I was sent in and for a time worked with the Methodist Committee for Overseas Relief in Poland to distribute supplies to the needy. I worked in this capacity until the communists, moving in, saw that we were making so many friends for the United States. They told us to liquidate our work and to leave. I left in April of 1949. I spent 1949 and 1950 in the United States before I was transferred to Liberia in West Africa.

Donald R. Lennon:

Here you had to learn the White Russian that was spoken in Manchuria and the dialect of the White Russians in Poland, and then you had to learn Polish in Warsaw. You had to spend quite a bit of time in language schools.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I had quite a mixture of languages and I never did master any of them. I could speak and ask questions and understand when people were talking, but my Polish wasn't ever very good. They said I spoke Polish with a southern accent and didn't make my consonant sound very strong.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know you went wherever you were assigned by the church, but what were your feelings? Here you had spent a year in the Far East and had seen the eastern influence and then were transferred to Eastern Europe, a completely different culture. What were your feelings and reactions?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I was so thankful. I'd seen so much hunger and so much suffering and I'd seen the cruelty of people to each other . . . I was just so thankful that I had grown up in the United States and had the chance to get a public education and go to college. I was so thankful my family was safe from all of that turmoil. I remember feeling just thankful every day.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was a great turmoil in every one of those areas that you had been assigned to.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

That's right. So when I was reassigned in 1949, I asked my executive that was appointing me to please send me somewhere where I would not have to learn another language. That is why I was sent to Liberia. Liberia was settled by the returned freed slaves from the United States and they spoke “southern” English. They would understand if you said “ain't.” I spoke of that accent, which was very different from the British English spoken in the British colonies near us.

Donald R. Lennon:

But the influence of the colonization effort of American slaves was sufficient in Liberia that the language traits were dominant?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

That is right. They went back and settled on Providence Island, a small island off the coast. The ship had wandered up and sailed down for quite a few days and the people on the coast were hostile and would not let them land. But finally they came to this Providence Island and landed. In fact, they would have starved to death that first year if it had not been that the tribal people shared their rice and fish they caught off the coast. So the little settlement grew and later they were able to get over on the mainland. The first Methodist missionary to Liberia, Melba Cox, sailed in 1832. The first boat landed in 1822 and they named the little settlement there Monrovia for the current United States

president, James Monroe. It became the capital, Monrovia, Liberia. There is a monument to the founding fathers in Monrovia and I think there are three Virginians whose names are on that monument--Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe.

Donald R. Lennon:

Made you feel right at home there, didn't it?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Yes, I used to like to go there. And the first president of Liberia, James Jenkins Roberts, was born in Norfolk, Virginia. He was a freed slave. His master, who had controlled him in the United States, had allowed him to study and he had learned and knew English and could write. He had studied history so when he went back, he made English the official language, and the constitution of Liberia is based on the constitution of the United States, which outlaws slavery and guarantees rights to citizens.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you at that time have the same type of tribal organizations that you had in most other African countries?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Very light, actually. There were the Bassa and the Mono tribes. One of the tribes had a sort of patriarch, tribal chief, who would hand his authority down to his son. But one of the tribes was matriarchal and the mother sort of ruled the village. The headman in the village was the father, usually the oldest man.

The people who settled on the coast tried to send Christian teachers to these tribal people so the would learn Christianity. They didn't get very far in, although they did have settlements along the rivers. In 1928, Doctor Harley went in. Until then, there had been no medical services and very little agricultural services to show the people how to vary their crops. Consequently, they were exhausting the land around the coast. They raised rice, but Doctor Harley was able to introduce them to the highland rice that would grow without all that flooding. He started, you might say, the first agricultural mission

and helped them to see that they had to eat something besides the rice. He planted a banana grove and urged them to have them near their villages; orange trees also. They used the brown rice so they got more proteins and vitamins. So Dr. Harley not only had the hospital, but he also helped with their diet. There would be many that would have died from the disease--I've forgotten the name--that causes the feet to swell up. Anyway, Dr. Harley helped many people in many ways. His wife, Winifred Jewel Harley, worked with him. She learned many of the wild things that were edible, like casaba greens. The casaba is the same thing we make tapioca out of. The casaba root, strangely enough, has some iron in it and when you cooked the root, it would have a dark streak through it that would indicate the iron. All the fruits, the kumquat--the Africans called it a plum--was also widely used. We also tried to teach them to use that and pineapple. Sour sop, it looked like a cactus, had thorns on it so it was hard to eat, but if you pressed it and got the juice out, it was very good.

We had a young A3(?) who came out just for a few years that understood dietetics quite well. When we would peel the pineapple out of the field, she would save it and pour hot water over it and let it stand awhile. It wasn't as good as pineapple juice, but it had nutritional value and the health of the girls in our home improved quite a bit.

Donald R. Lennon:

The home, I take it, was right in Monrovia?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

It was in an area called Sincore(?). It was not in the downtown area of the city. It's a part of the city now, but at the time it was outside the city limits and we were able to have a garden and grow some pineapples. We had one of those trees that had African plums and something they called butterpear. I can't remember the real name; the English

name is different. The Africans used to like to take it and spread it over their rice and eat it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sauce-like?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Yes. They would also cut the seed out of the palm and make palm oil. There were would be great clumps of seed up in the palm trees and they would cut those out. They called them palm nuts. They would throw the palm oil over their rice, which added vitamins and iron to it.

Part of our work was to help them improve their diet. We also taught the girls how to sew. Often, the African women who worked in the fields didn't wear any clothes except a loincloth. They would carry a child in a sort of a shawl that they would tie on their backs, and the little ones would sleep there. It was a little like an Indian papoose. The children would sleep while they were out planting the rice.

I think that we really helped them to improve their health a great deal.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you eat the native food or did you fix primarily western food that you were accustomed to?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I couldn't eat as much rice as they did. We ate native food, but I would always try to get some fruit. A man would come by selling fruit and I would try to get some extra fruit. I had this milk that you make up--it was powdered milk and it had a special name--and we used that. We taught the girls to drink it also. They didn't have cattle there because there was not any food for the cattle. They did have goat milk sometimes. We had one doctor out there who raised them specially so his children could have it.

Donald R. Lennon:

No pasture lands at all in the area?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

No, not there. The kind of grass that grew, marsh grass, would cut the tongues of cattle, so they couldn't have them.

Donald R. Lennon:

You talked about having your own gardens. Did you have seeds sent from the United States?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

A lot of things wouldn't grow, but we found that the mustard would grow and you could make greens from that.

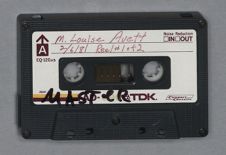

[BEGINNING OF TAPE 1, SIDE B]It has grown a great deal. We just had fourteen girls the first year, but very soon there were fifty-eight girls the last year I was there. That was in 1965.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did a lot of them come over here for college training?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Some came over and got their college training. I think one went to medical school. The Liberians sometimes would send their students to Mahari Medical College in Nashville. It was a black medical college. My doctor--I had a Liberian doctor--was a very fine doctor. He knew a great deal about tropical medicine. In fact, he was much better in tropical medicine than the doctors sent out from the United States. The doctor, who was in charge at Dr. Harley's hospital up in Ganta, was a Liberian who had been sent over and taken training here.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your work was with the girls at the school?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Yes, the College of West Africa.

Donald R. Lennon:

You did not get out into the rural area?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

When I would go for vacation I would try to go up country. Dr. Hyla Waters, who was one of our women doctors, was in charge at the Ganta Hospital after Dr. Harley came home for retirement. She graduated from a women's medical college somewhere

and I think maybe she had training at Harvard Medical School, too. But anyway, she was the only person in the up-country who ever did surgery. She often did surgery and set bones and treated a lot of cases they'd had to give up on before. Once, when a government official was taken very ill up there and they couldn't treat him at Ganta Hospital, or the government officials didn't think he could get treatment there, they sent him down to Monrovia to a German doctor. There was one German doctor who was very well known in Monrovia. He had his own practice and didn't represent any mission. When he found out the cause was appendicitis, he said, “Why in the world did you send this man down to me? You've got the best surgeon up there at Ganta Hospital, Dr. Hyla Waters!” So we know that there was a high standard of surgery and medical practice at the Ganta Hospital.

Donald R. Lennon:

How highly developed was Liberia at this time outside of Monrovia and your major cities? The natives were primarily subsistence level?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

There were many, many tribal villages, but they didn't seem to have war among themselves. There was a central government, which divided Liberia into provinces that had various districts and commissioners appointed there. They usually had some soldiers in some central point that they could send out to put down any tribal disturbances.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the natives primarily farmers or hunters or were there any kind of mines?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

The women planted the rice; the men cut down the trees in the forest for building the cabins and clearing the land. But the women were the ones that were farmers. There was a very high birthrate, but there was also a high infant death rate.

Donald R. Lennon:

The basis of the economy was primarily rice?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

At that time, the agriculture was rice. They were encouraged to raise more and more fruits. There were some banana plantations and some pineapple farms out from Monrovia. But they sold most of their things right there in the country.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not much mining like you think of in West Africa?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

The Liberia Republic Steel opened up a mine up in Bomi Hills. There were very rich veins of iron stored there. The Firestone Rubber Company had a ninety-nine year lease. The Republic of Liberia's constitution forbade people to own land or to buy it and own it. They could not do that, but they could have a lease on it and the Firestones came in and started the rubber plantations.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was this true of natives as well as foreigners? Were natives allowed to own land, or was it true for everyone?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Oh, anybody of African descent could own land.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was outsiders that couldn't own land.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Yes. And you know many Lebanese would come in and marry African women so that they could get some land; it would be in the wife's name, but the Lebanese would control it.

The Firestone plantation gave employment to many, many tribal people who would otherwise just have starved. And the Firestone plantation would bring in sometimes, even though rice was the basic crop, rice from Houston, Texas. The freighters would come in sometimes loaded with rice.

They found though once, when there was a shortage of brown rice and people couldn't get brown rice, they brought in this rice, which was polished rice, and many

people got sick off of it. That was their main diet and they developed pellagra and other illnesses.

Donald R. Lennon:

The polished rice lacked the nutritional value they needed.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

That's right. Well, I think the brown rice had a little protein in it. There was always a shortage of protein.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not much meat.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

No beef. Well, they got so they would raise some chickens and have eggs.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about in the up-country away from the swamp areas where the lowland rice was grown, was the same type of vegetation true up there--the sharp-bladed grass?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I believe they were able to introduce a kind of rice.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned the highland rice up there, but I was wondering, what the native vegetation was and animals?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

They introduced a kind of grass. Goats would eat anything, but I didn't like goat meat. We would occasionally have it. When they imported beef from South America we would try to get it. We tried to have some meat at least once a week so the girls would at least have that much meat.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was probably fairly expensive. And did you have proper refrigeration facilities?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

When I first went there we didn't. But we got it in the 1950s, I think, after they got an electric plant started. They had a hydroelectric dam on the Mesharada(?) River. It had falls and they used the falls to create electricity. We used the electric lights because we were afraid of fire if we used candles or kerosene.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of housing did you have when you first went there?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

We built in as much termite-proof concrete as possible. They did have old houses in town that would just fall down, even with people inside. They would have balconies fall and crush people, but we tried to have as little wood as possible in our buildings. We had metal supports and asbestos roofing. I know that in our girls home we had everything metal possible and had concrete floors so the floor wouldn't fall in. But we had the wooden door facings that held the doors because we couldn't have any hinges that would fit on concrete. Once, I recall, the door just fell in. You couldn't see in because the outside was painted, but the door joist was eaten out by termites.

Donald R. Lennon:

They had no wood there that was resistant to termites either, I don't suppose?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

There was what they called ironwood, but it was very hard to get. They wouldn't eat the ebony or the mahogany, I believe.

Donald R. Lennon:

The girls that were in the school, where were they primarily from? Did they come from the tribes in the interior or were they from the Monrovia area?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Mostly they were from the settled areas. Some of them did come . . . their parents had big plantations in the interior, but some lived right close. I think the furthest we ever had a student come from was Cape Mount up near the border of Sierra Leone and French Guinea. Some of those families were Mohammaden. We had some Mohammaden boys that went to our school and once I asked them why they had come to a Christian school, and they said that the College of West Africa was the best school in Liberia and they wanted to go abroad later. I don't know how the College of West Africa is doing now. They used to have to pay and the people were very poor. We provided scholarships. People here would often give enough to support a girl. At that time, one hundred and fifty dollars would pay family and would pay for all the food they'd need. It wouldn't buy

their clothing; their family would have to buy that. But a number that came from our school went on to be nurses and public health workers.

Donald R. Lennon:

Does the Methodist church still support the college?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I don't know whether they still give to it or not. They were trying to work toward self-support.

There was a military coup in Liberia last year. They shot president Talbert and executed twenty-three officials. I was told that the reason for that . . . it never came out exactly . . . was that the wealthier people, who were descendants of the first settlers, the English-speaking people, had bought up the rice and were keeping it in the grain warehouses to sell at a very high price that the people could not afford. The people were going hungry and when they got hungry, they made protests first and then made a raid on the warehouses and were able to get some rice. But when it happened again another year, the people appealed to President Talbert and to the vice-president, Bennie Warner, but they didn't get any help. When the government sided with the people, the wealthy ones storing the rice shot the president and his brother. They kept his wife under house arrest. They shot twenty-three people in the administration and people who were known to have the rice hoarded up, and then they opened the warehouses.

Donald R. Lennon:

A country in that geographic location with all this rice stored, I wonder what kind of rodent or insect problem they would have.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

They couldn't keep it from one season to the next. They would have to clear the warehouses. I think they did have rats.

Donald R. Lennon:

It would be self-defeating to try to hoard this stuff.

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Oh, you can't keep this for many years. You couldn't have done it.

Donald R. Lennon:

When did you retire?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

I left December of 1964.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were there about fourteen years?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

That is right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you see many changes over that period of time?

Sallie Lewis Browne:

Yes. The city was growing a great deal and the wealthier people were building their houses out on the edges of the city. It was spreading out and there were not many tribal people close to the city. The Cru(?) fishermen and I think one Bassa church was close to the city, but most were English-speaking.

[End of Interview]