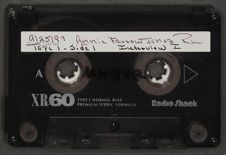

| East Carolina Manuscript Collection | |

| Oral History Interview | |

| Sally Phillips Smith | |

| June 12, 1973 | |

| Interview #1.8 |

Sally Phillips Smith:

About my age and all, I used to tell people that my age and how many years I've made and how much money I had are two things I don't talk about. I don't mind telling my age, the only thing about that is that it might conflict with some other things I've said which don't tally with my age now. You know how people go along and pick up things and put your age here and let it slip back. Then they go along and say, "Hey, you're not that old." For instance, I picked up some insurance, twenty-year pay, and I got it a whole lot cheaper then I would had they known my age. Well, twenty years are up now, and I said, "Oh my goodness, twenty years ago was along time ago." Well, things like that, you know, when you go back, when you're talking about your age.

Well, I don't know were I should begin. I could talk at length about my parents because they were slaves. My father was an only child. He didn't have any parents because he never knew his parents. His mother died when he was a baby. She was burned to death. My mother came from another section of the state. She came from the extreme eastern part of North Carolina. She was also a slave.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where?

Sally Phillips Smith:

In Hyde County. How she came to be here, she was a house girl, working in a house. She and her madame didn't get along very well. So, one day they had a run in. She

told her not to do something anymore, and she did it; so she picked the lady of the house, who was also, her mistress, and carried her to the door. She says she didn't throw her out, she just put her so near the steps and turned her loose that she fell out; and they said she threw her out the doors. Her husband says he can't have her here 'cause she'll kill my wife. So he told, her, and that's how she happened to be in this section of the country. And our home was from Nash County. Edgecombe County was where father was raised.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were your father and mother's names?

Sally Phillips Smith:

My father's name was Hilliard Phillips. There was a lot Phillipses in that section because everyone we knew was Phillips. My mother was Burgess. She came from another family down in Hyde County, right on the coast. I forget the name of the place right now, but anyway, she was away from all her people.

She was from a large family, but she never got in contact with them any more after that. They married right after, right after freedom. They raised a large family, a family of ten children. There were six brothers and four sisters, and I was number seven. They all lived to get grown. My mother used to boast that she never lost a baby. But they are all gone but me; I'm the last one. And I'm older than any member of the family ever lived, and so that's the age record up to now.

And they were. . .I'd say they were. . .My father must have been the progressive type, because he knew how to stay out of mischief, and he was an honest man. He never had an education, but he learned everything that. . .things he picked up. You know the kind of person. For instance, he knew all the Brer Rabbit stories. I don't know where he got them, but if anyone ever told them, he got them and told them to us; and that's how we learned them. I learned them before I could read, from him. He was the progressive type

from that point, and then he was progressive for the fact that he liked to help. He didn't have any education himself, but he liked to help others who do have education. Because he was honest and he was a progressive type, as I said, he helped other people get positions he wasn't able to hold because of him not being educated. He was good along that line. He raised all his children; and after he passed the age, he must have been past sixty, I guess, he bought and paid for 103 acres of land.

The children had long been out of school. As I said, I was number seven; there were three below me. The younger they were the better chance they had at an education, naturally, because the others had to work. But they all had families, and we are a big family. The Phillips family is one of the largest families now, when we have our reunions and hundreds of us get together. And what else can I say about him? He bought this place near the point where Nash, Edgecombe, and Halifax counties join. A school, you know, philanthropists used to build schools in the South. Well, some lady, who had lost her husband, had a lot of money in New York, built a school there, and named it in honor of her husband. She called it the Bricks School. You know it was quite an institution of learning for people in this section. I was nine years old before I learned to walk the three miles to school because it was too far. I said I was nine years old before I was able to attend school because I lived in a backward section and because the schools--the public schools-- were so far apart. When this school was put there, you see, he bought this place four miles away. He bought a farm about four miles from Bricks School.

This school lived to be, let me see they founded that school in 1895, and it lived until the First World War; then they tore it down, to keep the soldiers out of there. That's what I heard, I don't know, but they burned it and tore it up. It doesn't live now. She bought the

land and had a big building put up their--brick-- and named it after her husband. And then someone else who had money would put up another one, until the whole place was just a campus of brick buildings. But I'm saying it lasted for, let me see 1895. . .When was the First World War?

Donald R. Lennon:

1917

Sally Phillips Smith:

They destroyed the building, they said, to keep the soldiers out. That's what I heard but I don't know. They burned it up and tore it up. There's no trace of it now, though, except the campus, but the two-story brick buildings were all torn down. This lady, she was a wonderful person. Her name was Mrs. Bricks, of course; she named the school John K. Bricks after her husband. And that was quite a life in that community. We went to school there, me and my younger brothers and my brothers' children. All of us had a chance to go to that school. And I was practically raised on the campus.

Donald R. Lennon:

When did you first start attending Bricks?

Sally Phillips Smith:

In 1897, the second year after it was built. It was one year old when I went there, and it was called Agricultural, Industrial and Normal School. It grew to be a junior college later. It just built on and on and on.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many years did you attend?

Sally Phillips Smith:

Oh, I'd say about five years. I grew up on the campus. I was kept there because, you see I was number seven. All my sisters were older than me, and they all married, and then there were my brothers-- three younger than me. My father had bought a farm, so I had that chance, the opportunity that the others didn't have. They just kept me on campus so I wouldn't grow up and marry soon. So, I stayed there through all my teenage years, I was going to Bricks School there.

My parents died, my Father in 1911, November 13, 1911. My mother died one year later, 1912, to the day. So, I began teaching and doing all I could for those who were younger--grandchildren then. I had three brothers younger then me, one of them was in college at Fisk, and all the rest of them married. No, the one next to me didn't marry, he died. And this one. . .which one was it?. . . not the one next to me. The next one was named Matthew, and that was his son: Donny, is that brother's son's son. See, he's my great nephew.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of impression did Bricks School make on you when you first started attending there?

Sally Phillips Smith:

It made the kind of impression on me that you have to work to win. In fact, you see, it was an industrial school; everybody who went there had to work at least one hour. I don't care how much money you had. Of course, very few of them had enough money to pay back eight dollars a month, so you just had to do one hour's work. You could cut down on your expenses, your dollars, by working more than one hour. You could work two hours or three hours, and some worked their whole way through.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did they have, a farm to work on?

Sally Phillips Smith:

A farm, yes, it was about a thousand acres. It's still there. The farm is still there, but the buildings are down. Now, my brother lives near there. Of course my father's farm was there, my brother bought a farm near there, and people bought the land around the school building. But when the school was diminished, you see, and the older people died, that made a difference.

Donald R. Lennon:

Can you remember any other experiences, any particular stories pertaining to the time you were at Bricks? Anything that sticks out in your mind in the way of instances that happened to you while you were there?

Sally Phillips Smith:

Well, one thing that remained in me is that I like to read. They used to call me a bookworm. I think that is one thing that is wrong with my eyes now. And, I liked to sew. I graduated from the first sewing group they turned out. Dressmaking. . . I got my diploma in sewing. I liked that, and then I liked to read. You see, the library grew with the school. People in the North sent down books and all like that. They got them from wherever they could and built the library. I used to read all the stories as fast as they would come in. I majored in English. I liked that.

Now, this boy, Donovan, I named his father from one of these stories I read, an Irishman who made an impression on me. I like strong people, you, know, people who can stand a lot. I named him Donovan. The other one, I named him for, Scott's "Lady of the Lake " Sir Roderick Newlin. That's where they got their names. I think I inherited the knack for remembering things like that. I think my daddy would have been very smart if he had been educated. In fact, I know he would have been quite a scholar. So, I picked things up like that, and he would tell me, " Whatever you get in your head no one can take away from you. So be sure of your head."

And then I always liked people, I could always get along with people. It would always be the thrill of the day when I'd go on campus. My father was this type of man. You see, there were children on the Bricks school grounds who worked their way. That is, they would have to stay there when school was out, and work all through the summer, on the farm. They had fruit trees around there, and they canned and all that kind of stuff. They had

a laundry, and they would work all summer. Others, who could pay their way, went home. Well, here's what I used to do. I used to take people home, a group. I would make out a list of people I liked, you know, who didn't have any place to go during the summer. They would be like from Raleigh, or way off in some other part of the state and they didn't get their vacation time. They didn't have but one week of vacation. And they'd go out to my father's farm and spend the time with me. I would invite then out there. My daddy didn't care how much company came because he raised his own food.

He used to invite the faculty out there every year to dinner, and he'd sit down to his table and say, " Everything on this table is raised except the wheat, the bread, and he had corn bread, but the loaf bread was the only thing." Everything else he had gotten off his farm. He liked that. He enjoyed entertaining. He liked people, and people liked him. He was very jovial. And that's what I would do, I'd have company all through the summer. And I was never alone. My mother wouldn't care because she would have her cow, garden and chickens. She sold butter and she always got five cents more on the pound at the market where she sold her butter than anybody else who sold country butter because she made what you call sweet butter. She sold eggs and butter and all like that. This grew out of the fact that she was a house servant and worked in the house when she was a slave. So, when she got the farm, she just didn't figure that was her job. So, she worked at her work all the time with her garden and her chickens and her cow. I never knew my mother to work a day in the field, and this is quite unusual because everyone else was working. She had a mind of her own. She threw her bosslady out the doors. But she had a knack for making friends. She thought a lot of the white people. She got along nice with the white people.

When she passed away in 1912, a white minister came home and preached her funeral. You see, congenial, that's the type they were. My father was a politician he--carried his gang. He was a stump speaker. I said," Donny had it in his blood because my father was a born leader. He just wasn't educated."

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you say he was a politician. Did he become directly involved in politics during the 1890's?

Sally Phillips Smith:

You know the school here named Eppes High School? Well he got that man, and that's one of the reasons I'm over here in Pitt County instead of Nash County. I got better work here in Pitt County. I could have worked in Greenville, but it was cheaper for me to work in a smaller section where I could live cheaper. But he told me anytime I wanted to come here and work, I could, because my father had caused him to go. . . .where did he go, to Raleigh?

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, his brother was in the General Assembly, yes mam. The man the school is named for was brother to the legislator.

Sally Phillips Smith:

He said that because of my father, he would give his children a place, a job that he had anything to do with in Raleigh or in Washington. He got some of them government jobs in Raleigh and post office jobs here, and then they would get kicked out. If they ever got a job here and got kicked out of it, they'd go to Raleigh and get a government job of some type.

There were a number of people like that who knew his influence, and they say he helped them. People liked him, because he was honest and would never sell anyone down the stream. There were other people like that. I remember the names, but I don't know what they do. Some taught, some of them got in politics. There was one man, Battle, who got a

post office. They kicked him out, and he went to Washington and got a political job. I don't know what he did, but you know, they can always find some fault with them if they got a job like that in the post office to get them out. The only thing they could let them do is teach. And they'd only have school three or four months at $25.00 a month.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many years did you teach?

Sally Phillips Smith:

I have a plaque that says forty-four years, but I had more years than that, because when I began teaching, I was in a different section, you see, before they started keeping records. When I was teaching for $25.00 a month, they were not keeping records. They could have traced them back, but I said forty-four. I guess I could have made fifty if I could have gotten them all.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tell us some of your experiences as a teacher.

Sally Phillips Smith:

As a teacher? I began teaching in a one-teacher school. When I began I go$25.00 a month, for four months, $25.00 a month. That was it. And of course, that didn't last except for three or four months. Then I went to summer school and night school until I worked up so I could make more then twenty -five dollars a month. I kept increasing my ability for teaching, you know, every chance I got because I had all the year after four months. I could sew. I used to work on the side like that because I could always get a job sewing or something. I would do anything because I had to work. After awhile, you got looked up to. I taught for a number of years for less then $50.00.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this in Halifax County or Edgecombe County?

Sally Phillips Smith:

No, it was in Nash County. My home was in Nash. And I taught up there in Nash County. When I left Nash County, I came to Greenville, Pitt County, although I didn't live out here. I moved to Kinston; that is where my headquarters were, and I taught in Pitt

County most of the time. I taught in Martin County just one year. But most of my teaching profession was done in Pitt County in a little village about six miles from here, Simpson. See, I could live there for less than half the expense I could live in Greenville. I also had nephews that I was interested in. Donny's father was one of them, and his brother was the other one. You see, they were left orphans, and all the other people had big families; my sisters had big families and my brothers had large families. I didn't have any family, and so I just took them over and saw to it that they had a chance at life. It didn't matter, I didn't have anything else to do. So, I just worked where I could save my money and keep them going, especially after they started school.

The best friend I had was a white woman in Atlantic City. What was her name? She was a nurse. You know, we used to be up against it all the time for material to teach. We did not have anything but the children. And sometimes they didn't have but one or two books, one book maybe; and they didn't have a desk or anything; and nothing was furnished. It was kind of like when they went down in Egypt and had to make something without straw--make their own brick without straw. Well, this lady, I met her in Atlantic City. I got a job there part time, and she and her husband were there. And I met her, She lived on the beach in Atlantic City in the summertime, and in the wintertime they went to Florida. And I went down to work for her, and soon she got to liking me. She said that she'd never forget me, and she didn't. After that, she gave me material which enabled me to do a lot of things with my school work that I wouldn't have been able to do, because I wasn't able to buy. But see she was in New York, and she used to send me things--paper and books and materials.

At Christmas time, she sent me enough candy for each of my little children. They remember it now because she sent a whole bag of Christmas candy in containers of Christmas things. Other teachers couldn't do it because they didn't have any money. But I had her behind me, and she never forgot me, just like she said, "As long as she lived." She lived to eighty years old, and I guess I was one of the first people to find out she was dead. I think there was a sister who notified me when she finally died. But that made me able to do better work than I would have been able to do, because I didn't have any materials to do with. I had these two children that I was interested in, and I worked at that little place out there, Simpson, that was called Chicod, which was the name of the post office. The name of the place was Simpson. On weekends, I'd go to Kinston. And I kept up for . . . how many years? I worked down there for seventeen years. And most of the time, I lived with those people. They were nice to me. I told them they took care of me, and I took care of my other obligations because they took care of me. I worked there with them all the time. I had things sent me from the North. You know that lady had friends. She said I was a missionary. She said, " You are a true missionary." So she sent me things, and then she had a Sunday school group in New York--very nice people-- and they would send me things. So I was quite popular. I always had something to give people, and they always had something to give me. It cut down on my living expenses, and I got away with it. The boys got through school, and then when they moved here and got into business, Phillips Brothers, I came to live here in Greenville. That's the only length of time I've been in Greenville.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you teach in Greenville?

Sally Phillips Smith:

I didn't teach here in Greenville.

Donald R. Lennon:

You retired in Simpson?

Sally Phillips Smith:

No, I retired from another school. I retired from Pitt County, but it wasn't in Simpson. They had supervisors then, you know. The people of Simpson wanted me to stay there; they tried hard to hold on to me. But what happened, the supervisor began to consolidate schools. When I came there, the supervisor was a man, and when he got off the field, the supervisor was a lady. She was a friend of mine. They consolidated a school, and she wanted me to leave Simpson and come to a school where her headquarters were. People didn't want me to go, and I didn't want to go. I was getting along alright where I was. But if I didn't come to the school were she wanted me to come work , where her headquarters were, then she wouldn't let me stay in Simpson. So she made me go to another school way out here in the country, and I taught there, and that is where I retired from. But I would have been in Simpson right on. She just didn't like it that much, because I wouldn't go where she wanted me to. The people came--the people from Simpson came up here to see the superintendent. They tried and tried, but the superintendent said," No, the supervisor said she had to go." So, I left.

When I retired from teaching there were only two, I was among the first two retired teachers who got any recognition. We had a big banquet at my church; but from then on, they began to have recognition, and the teachers would get together who retired and have recognition. I taught under a Mr. Fitzgerald and Mr. Conley, and that's about all. I think Mr. Conley was the last one I worked for. They were both nice.

Of course, I married at a late date. After I got through doing everything else, then I got married.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh really, after you'd retired?

Sally Phillips Smith:

After I retired from teaching. My nephews were established in business; we had this home and I didn't have anything else to do, so I got married. I moved to Baltimore, and I spent all my married life in Baltimore. I came back here, where I was Miss Phillips, and they don't know me as Mrs. Smith. I call up old friends as Mrs. Smith and people don't know who I'm talking about. They still call me Miss Phillips.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you like Baltimore in comparison to North Carolina?

Sally Phillips Smith:

I liked Baltimore. I like my life in Baltimore. See, that was something new. I lived in an apartment in Baltimore; it belonged to an Episcopal church. It was built for retired people, and I got in there when the building was new. I got married and got in there when the building was new and got my apartment. He was retired, and then I had a few years of very happy, contented life.

I went back last year, was it last year? When did I go back to Baltimore? Last month, wasn't it? They had an affair and invited me up there, and I went up there. It was like going back to school after a month's vacation; they were all so glad to see me. I had a good time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, how long have you been back in Greenville since you moved back from Baltimore?

Sally Phillips Smith:

A year next month. Just one year next month.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you were up there for quite a few years then?

Sally Phillips Smith:

Not too long, but I lived there long enough to outgrow most of the people, my associates right here, you know. Most of them had passed on. So, I feel very much alone. The teachers and the people in the church, things are quite different. But then ,you know, old trees don't transplant readily.

Donald R. Lennon:

But this was home, when you moved to Baltimore, that's when you transplanted.

Sally Phillips Smith:

Transplanting, but when I got back here, that was another setting. I haven't taken root yet.

As far as my father's politics, I don't know anything other than that the only thing he could do was to help others because he wasn't educated. But he was a leader because he was honest and a good mixer. After he passed, the people on the street," I'd give you five dollars to hear old man Phillips laugh." He was jovial. He had a knack on learning the poems that other men wrote. He'd write things that I would like, you know. If I heard a poem a few times and I liked it.

Donald R. Lennon:

As an educator, what did you teach, English or what?

Sally Phillips Smith:

I taught first grade. I had first grade. They had to be amused. Keep them in good humor so they would be learning. Teachers don't get the technique of it now very much, because they think-- I don't know. I never had any trouble with children and I never had any trouble with children's parents. We just lived together and had a good time.

Donald R. Lennon:

It's all in knowing how.

Sally Phillips Smith:

That's right, and I knew a rhyme or poem for everything that came up. I'm not that good now, though. But I used to could teach children in poem or rhyme, and it would stick better in their story. My daddy was a great storyteller. And I used to that for children.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you remember some of the stories he told you?

Sally Phillips Smith:

Yes, his favorite story was about the lark and the young ones. You know that, don't you?

Donald R. Lennon:

No, I don't believe so.

Sally Phillips Smith:

"The Lark and the young ones": the lark built a nest in a wheat field, and they had the young birds in the nest. The old birds went off to get the food, and they told the little birds to watch the farmers when they came, because if they came to cut the wheat, they would have to move. And so, when they came, they asked what he had to say. They said that the wheat would soon be ripe, and he would have to get his neighbors to come and help him house it. So, they said, " It's alright, don't you be uneasy." And they went off the next day, and they came back and asked, " What did he say this time?" and he said," My wheat is ripe, and I'm going to get my sons to come in here tomorrow morning and cut it before it spoils." The parents said to the young, " that's all right, you just stay quiet, and notice everything that is said. " And then they went away the next day and came back, and the little birds were all uneasy, and they said," what did the Farmer say?' And they said the farmer came in here and he said he was going to get up tomorrow morning at daybreak and take his scythe and cut his wheat himself. The parents said," We have got to get up, come on, get you things together, we've got to move, when a man decides to do something himself, then you are going to see action." One of my oldest brothers, I got this from him, and he must have got it from my father. " One simple John Proctor, a hedger and ditcher, although he was poor, did not crave to be richer. For all useless troubles in him was prevented by a fortunate habit of being contented. Why should I mumble and grumble, he said, if I cannot get meat, I can surely get bread. And while fretting may make my calamities deeper, it can never cause bread and cheese to be cheaper."

You know, I taught first grade. I didn't always teach first grade because that wasn't my work. I didn't like first grade. You had to--they keep you under feet and you had to talk all the time you know.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine that is more demanding, the small children, than it would be with the older ones, would it not?

Sally Phillips Smith:

You see, that's why I didn't prefer them. I liked third and fifth grades. But one year, the supervisors had lined the teachers up, there weren't but four or five of us. I didn't like big groups, you know. I always look out for my experiences, because I could do for myself. One of the teachers that was supposed to take first grade said she wasn't going to have it. It was time for school to open, and the supervisor said," Well, if you'll just take it this year, then next year, we'll make other arrangements." She said," No, because if I have had to teach that first grade the first year, I won't teach at all." That made a difference, you see. Nobody wanted little children. And so, he asked me. He said," Children like you, Miss Phillips. I wish you could just take it for this year; and the next year, I can arrange to have a person teach it." And so I took for just that one year, because I had been teaching third grade. And after that, I couldn't get rid of them. They just hung on to me, and I hung on to them. I made them my saving grace. When I retired, I had children that I couldn't promote because they wouldn't leave me. They wouldn't go to school unless they could come to me.

You know, some children are problems, problem children. One particular child had tantrums, and her mother wouldn't force her to come to school because she was too little, too young at the beginning. I found out what was wrong with her, she was anemic. And I almost got out with peanut butter. I got so I couldn't stand the thought of peanut butter. Here's what I'd do, I'd make that child come sit near me so she wouldn't bother the other children. And she'd sit there and after awhile, she'd say, " Miss Phillips, I want to eat some now. " The other children would say," Eating in school?" I knew what she needed, and I said, " all right." And I'd let the child eat. She'd sit there and nibble on this peanut butter, and then

she'd put it back in her paper bag. That's what she had it in. You know, one of those spells would come on. I wasn't afraid of her. I wanted to get her over it, and we got along nicely. So she came to school. I didn't punish her because she didn't act like other children. I found out why she wasn't acting normal. One reason was because she wasn't getting the proper food. So, I used to divide my lunch with her. Oh, children used to come to school. . . you know, people just didn't hardly feed children then because they didn't have lunches like they have now. And I used to divide my lunch with them. Sometimes I could go better without the lunch than they could. And I have cured many, many a stomachache with little children with a graham cracker and a glass of water. I 'd carry me a box of graham crackers, and I'd give them a cracker and a glass of water, and they'd perk up. They weren't being fed.

There was an old teacher in the county who said that I was the only teacher in Pitt County that ever raised a garden in my classroom and fed it to the children. We had large windows, and my windows opened on the south. I put two boxes, big boxes in the window, and then I let the children . . . I had to teach, what was it? I forgot what you call it now that you teach the children. And that's what I taught mine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Science?

Sally Phillips Smith:

That's what I taught, science, to the children. I put that up there and got catalogs from different seed firms, you know, and decorated on the tables where the boxes were. Then I let each child bring seeds from home. Each child would bring some kind of seed. I'd let them dig a little trench. It was easy to get soil, because I was right out there near the woods. They'd get this nice woods mold, you know, put it in there and then dig a little trench, and they'd put there little seed in. One child would bring some onion seeds; someone else would bring some tomato seeds; some others would bring some salad seeds;

others would bring some string beans; someone would bring something else, until they got that whole box full with little rows. They had a fit over it; everybody wanted to tend this garden and it actually grew.

The supervisor, when she came to the county, said that it was the greatest attraction she'd ever seen, a garden of vegetables growing in a classroom. I had a place larger than that. And you know, most of those plants grew and matured right there in the classroom. The string beans got grown; the onions got big enough to eat; and the salad got big enough to pick, and the. . . what else did we have that got big enough to pick? Anyway, it grew there during the winter, you see, and then when spring came, it had matured. The room was heated with one of these pot- bellied stoves. I got a big pot from some parents, and put it on the stove. They gave me a big old ham bone. I put it in there. And I let the children pick these vegetables off and prepare them and then somebody brought tomatoes. And by the way, we sold the tomato plants because they were to early, had the plants really early. The nurse came along and gave us money for the plants, the tomato plants we had raised, to buy crackers for the soup. A neighbor gave us some tomatoes that she had canned to put in the soup. And another lady gave us a nice big ham bone to put in there. And I put that pot on the stove and put vegetables in there along with some other things those people had bought, and made a big pot of soup. And when lunchtime came, everybody had a little jar and a little spoon; and they ate up the garden.

They learned how to make variety, you know. Most of them like that. Where I used to live in Simpson, they'd have sweet potatoes and collard greens. That's all they knew to grow-- sweet potatoes and collard greens and corn during that season. After that, they didn't have any vegetables. I taught them to make broccoli-- get something you can raise all year,

you know, to have a diversity of crops in your garden. And where I stayed -- I stayed at one place, the lady I stayed with for thirteen years, and when I went there, she was feeding me sweet potatoes and collard greens. After I stayed there a while, she had a nice variety of vegetables in her garden. I liked vegetables, you know. I taught those people everything I knew. I taught them everything I learned during school, and I taught them everything I learned on the farm. They helped me, and I helped them. But they said nobody else had ever raised a garden at school. What I did, I had a book-- I ought to have it somewhere now-- where I kept a record when the seeds were planted and the time they matured, and the different seeds that were planted. School closed in May, and some things you couldn't eat up, you see. Then I had places out at the edge of the playground, and the principle would let those children bring a hoe or something and dig out there and they kept on making their garden. They had those things growing out there, and the supervisor came and took our picture around that little garden. I've got it somewhere. That was an experience that I enjoyed and the children enjoyed. You feel alive, and you keep from growing old because you feel alive with what they are growing, and you grow along with them. Losing all my family from time to time like I did, you know, until I'm the only one left. . .I had the children, after I had retired. I had to retire, because I was too old.

Well, one problem was attendance. You see, the children had so far to travel. Just like I said, I was nine years old before I was big enough or strong enough to go to school because you had to walk three miles, at least three miles one way. You see, for a six-year-old child, that was too far, especially for someone small like me. We had that problem. And then, when farming time came, the children didn't come to school hardly at all because they had to work. And the little children, if they were big enough to take care of the babies, they

had to stay home. There wasn't any way to get them there. Of course, we had a Parents and Teacher Association, but there were so many people who wouldn't even pay that any mind, you see. So, attendance wasn't as good as it should have been. I used to get my children to school by making it attractive, you know, having something they'd like. Now, I was in a village where they didn't have so far to go, you see, all down in that little place of Simpson. You haven't ever been to Simpson, have you?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

Sally Phillips Smith:

All around there, they owned their homes for the most part, and it was thickly populated. The children could get to school from the time they were six, you see, because so many of them were in walking distance. Then, they had this advantage of nurses who would come through, you know, and help. And when I went to Simpson, they had that place there. Tuberculosis raged, you know, they had those little houses built over there. I had one child in particular that I was so proud of because he wasn't five years old. He didn't live far from school, and he used to come sit in my classroom, and his mother had to work. As long as I had sitting room for them, you know, I'd let them pile in there whether they were sick or not. I couldn't put them on the road, and I could take care of them and give them a graham cracker. So, I just kept them in there like that. One little boy in particular was in the classroom; before he was five. The nurse came along to examine the children for tuberculosis, and he had it, again, at that age, between four and five. There were already other children who where out, you know, in these little houses. They didn't have a sanitarium, you know, near like the one they have in Wilson. There wasn't one that near then; it was way away, or somewhere. Well I got this mother, with the other teacher's help, to let this child go to the sanitarium. He was just a baby, and she hated to, you know, send

him so far away. But we offered to give her travelling expenses to go see him sometimes, and she finally consented for him to go. While these children who were in these little houses died just like flies, this one lived to get grown because his mother let him go to the sanitarium, and he out grew it. He got grown, and he was a healthy young man. He outgrew the germ. Those little houses were just big enough for a little bed. There wasn't any place in there for anybody to. . . I don't know whether there was any sitting space in there or not-- it was too small. They were supposed to stay in there all the time, and you'd just go feed them. They weren't supposed to mingle with the other part of the family. I thought it was the most pathetic. . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they given any treatment or anything?

Sally Phillips Smith:

Yes, I guess they treated them. They gave them something. But see, the point was to keep it from spreading. The mothers were supposed to take care of them out there. But what would happen, when night came, a whole lot of those mothers and parents would take those children inside. They wouldn't leave them out there in the yard. The little house would be out near the house where they could have it open you know. They'd take them inside and put them back out there in the day.

Donald R. Lennon:

And the rest of the children or the rest of the family would probably contract it from them.

Sally Phillips Smith:

That's it that didn't cure it at all. But they needed to be taken away, out, just like we got this child out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, if they had left them in these little houses during the winter, they would have frozen. Was their heat in them?

Sally Phillips Smith:

No, there wasn't heat in them. There wasn't any light. A lot of little children died. They'd keep them out there, then they'd die. But this little fellow, I called him my baby, because I said I was proud of his mother because she had enough presence of mind to let her baby go to the sanitarium and get well. I had these other little children, you know, who would make drawings and send to him, and then they'd write notes. Anything they could write and send to cheer him up. And I told her I was proud of the mother because she saved his life. That was one experience I had that I was proud of.

I'll tell you one experience I had when I was teaching in a one-teacher school. I taught in a one-teacher school for several years. I have taught in one-teacher schools when I'd have -- I had one hundred children at one time, in a one-room school. We had a good time. The big ones would help with the little ones. We didn't have any desks; we had seats, long seats like desks or pews like coming out of old churches. They would put them in the classroom. I had a whole room of children. The place was full. A whole lot of them had never had Christmas trees. I remember one Christmas I was teaching there, I had five grades. Of course, little children then weren't taught anything but ABC's and to make the letter, and make figures, you know, things like that. I knew all that when I went to school. But I had these children, five grades. Some of them were teenagers, quite a few of them where teenagers. They could help with others. And we didn't have any conveniences; didn't even have a pump on the grounds. We had to get water from a nearby house with a pail. I don't know how they got along then.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where did you get the wood for the stove?

Sally Phillips Smith:

Out of the woods.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sent students out to cut . . . .

Sally Phillips Smith:

Yes the children would go out in the woods and pick up wood and bring it in the evening and pile it up and make fire in the morning in that heater. The first one who would get there, and that very often would be me, and I'd make the fire. But I had the children bring in the wood before we left in the evening, and then I'd get there and build a fire in the morning.

But on this occasion, I never had that many children, but children aren't anymore now like they were then, than chocolate is like cheese. I could tell those children what to do, and they'd do what I'd tell them to do. I said," If I'm not here at a certain time, you go n and open school because school is supposed to be open at 8:30 or 9:00."

I had a bell I could ring, you know, like that at the door and they'd come in. I have been to my school when was teaching in a one-teacher school, and when I got there, those children wouldn't be anywhere out on the playground. They'd all be in the classroom singing our opening exercises. The big children would take care of the little ones.

I'd teach the big ones, and the big ones would teach the little ones. That would keep me from losing any time, because I'd have to walk two miles, sometimes two and one half miles to school. And sometimes I would have to clean up the classroom before I left.

But this particular school I was in when I had all these children one-year--I think it was the first year I was there--They had never had a Christmas tree. So, I had to get a Christmas tree out of the woods because we were right there where we could get a holly or cedar. I had them get a cedar tree. And I had them make colored paper, cut into links and make links of paper, different colors and string it around the Christmas tree for decorating. Then they could get mistletoe and holly and put it all up there and make a pretty tree. You

could see it from the road. People said you could see that pretty tree in there, and it looked right beautiful.

And the day before we had the Christmas tree, I had the children make gifts for each other. I encouraged them to do that. And I made it a point to have something, something, if it wasn't anything but picture, for each child. I don't know how many children I had then, I don't think a hundred of then, but I had about seventy five. Anyway, I had something on that little tree. The large girls tied the things on there in the mornings and everybody had a little gift, The girls who were in the fifth grade could help put them on there, and then we had a little program. We sang some Christmas songs, had Christmas poems, and then they picked the things off the tree and called the names. Every child in there got something off the tree, and I didn't get anything. They forgot all about the teacher. They hadn't been taught to give. Nobody ever knew how badly I felt after I had worked and stayed up about half the night fixing things for all those little children, and then I didn't get a thing off of that tree.

But I didn't mind, because they'd had the experience. But that was the only time that I fixed a Christmas tree at school and I didn't get anything. Children learn, you know; they learn by doing. And they hadn't ever been taught. They didn't know how. Their parents hadn't been taught; they didn't know how. And so, they learned, and that was an experience that I had.

The supervisor or some people would just come out. They wouldn't tell anybody. Nobody bothered you. You know, public schools like that, the only schools in that area were little one-teacher schools, they didn't have time. We didn't see any of the officials.

Now, the Bricks School that I lived near, they were interested in the progress of the community. And so, they used to have what they called a Farmer's Day, when they'd have -

-the farmers would get together and do things, you know, and have a speaker to encourage progressive farming. So, on one occasion, they offered a prize to the public school that would -- there were certain things that they'd give prizes for. And this same little school that I told you about had this Christmas tree, I had my group enter this contest. They had to make picture books. They had certain directions to go by, and they made picture books.

Another thing they had was for bread--the best loaf of bread. Nobody was making loaf bread then; everybody was eating corn bread. Nobody made bread at home, and they wanted to encourage it. It seems like they had some sewing or something like that.

Anyway, when time came, my school got the only prize, got the prize on the picture books and the prize on the bread. Of course I didn't make it, but I had it made, you know. Somebody in the neighbor hood did it, they hadn't been making loaf bread, but some parent, I had gotten them interested at that point. So, she made a lovely loaf of bread. And we had that on exhibit to pick up. And we had the picture book, we got that prize. It seems like there were three things. But anyway, the other teachers didn't. . . I didn't keep them from working though. But I was just interested. I just put all I had into my work, and so my children got the idea. They were tickled, those picture books.

We had slates too. We didn't have much paper, had slates and a pencil. I was so small you couldn't tell me from the children. Parents and ministers or somebody who would be coming through and come in and walk in there and ask the children," Where's the teacher? You don't have any teacher today?" they would say," there is my teacher." I looked like one of the children. " That is Miss Phillips, my teacher." I would have to stand up. I had a good time with the children. But for one teacher, it was too much. I don't know, I got to the place where I didn't like it. So, I went to Williamston in Martin County and got a group

where conditions were better, and I didn't have but one grade. I didn't have to be--didn't have to do all the thinking and all the painting and the entire fire making and all those things like that. But I had the advantage of having bad children. They weren't like children in the country. My headquarters was in Kinston and I --they didn't have any buses like now.

They had railroads and it took a day to get from Rocky Mount to Kinston to Williamston. There was another place I had to in Nash County that was hard to reach . I couldn't stay in Williamston, but I liked the place. That was just the size group that I liked -- six or eight teachers, you know, and one grade. And then, of course, wherever I went, I had charge of the sewing and that kind of work because they found out that I had home ec. They found out that I had that sewing diploma. I found out pretty soon after I left school that I couldn't make my living sewing. That diploma was no good to me. I don't even know where it is. I put it down and went back to school every night and every summer that I could until I got myself on a payroll that paid. I paid for it, but it was worth it because, you see, after I left the field, I was able to get income. I made hay while the sun was shining. I took that much after my dad. It wasn't an easy road, but I tell you, I took it.

That was the old home place where they all lived. It was a big house, and they had lived there near that Bricks school, and all those children had been to Bricks, and most of them graduated from there. You see, they had all the history and everything around there. That was a house by the side of the road, and it got burned down on Sunday while they were at church. That was last year--just last year--nobody in it. A lot of things got lost then that cannot be replaced.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well that's always true with personal papers, such as letters and things of this nature. When they're destroyed, that's it. No way to replace them.

Sally Phillips Smith:

I have a trunk that I've had with me. I don't know what's in it. I haven't opened it since I've been back from Baltimore. I didn't take that when I went to Baltimore. I didn't think of anything except my bag because I didn't go there to get married. I went there and made my mind up and married while I was there. I stayed there, and so I never did move my trunk. Most of the students of Bricks, most of them are gone. You don't find any of them hanging around like me for I don't know what.

[End of Interview]