Interview of Nell Cole Graves

| Interviewee: | Nell Cole Graves |

| Interviewer: | Michelle A. Francis |

| Date of Interview: | June 8, 1985 |

Michelle A. Francis:

[It is June 8,] 1985 and I'm talking with Nell Cole Graves at Seagrove, North Carolina. Nell, what I usually do is just have people start out by sayin', uh, givin' their full name and when they were born and where they were born. So, your name is Nell.

Nell Cole Graves:

Nell Cole. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Graves.

Nell Cole Graves:

Graves.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. And you were born here in Seagrove?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm, well it was Steeds, Asbury then. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

It was called what?

Nell Cole Graves:

Asbury.

Michelle A. Francis:

Asbury?

Nell Cole Graves:

Asbury when we got our post office.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really? When was that?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh, 19--when was I born, 1908.

Michelle A. Francis:

1908? What month and day?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh, November the 7th.

Michelle A. Francis:

November the 7th. Well, that's good. 1908.

Nell Cole Graves:

1908.

Michelle A. Francis:

Waymon said he was born in 19--he didn't say 1902 did he?

Nell Cole Graves:

He was born in [unintelligible]. He was six years old, I mean, wait a minute now, he's four years older than me.

Michelle A. Francis:

Four years older?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Four years older than me.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were you born here?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

On this property here?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

And your daddy's name was Jason?

Nell Cole Graves:

Jason, mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Jason? How did he spell his name?

Nell Cole Graves:

J-A-Y-S-O-N.

Michelle A. Francis:

J-A-Y-S-O-N. That's an unusual spelling isn't it? He was a potter.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

And his daddy?

Nell Cole Graves:

I don't think he added the--Jay-son, J-a-y-s-o-n.

Michelle A. Francis:

S-o-n?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. He was a potter all of his life. He started when he was a young boy.

Michelle A. Francis:

So did you start when you pretty young, too, didn't you?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. I started on the wheel when I was 13.

Michelle A. Francis:

When you were 13?

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Goodness, that was young. Is that when you just started makin' pots to sell, or were you just kind of playin' around?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, I was playin' around before then.

Michelle A. Francis:

You were?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

When did you start playin' around with the clay?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, I was playin' around when I was about, uh, I guess around nine years old.

Michelle A. Francis:

Nine years old?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. And then I made 1ittle frogs and things, you know, to put in flower bowls?

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Nell Cole Graves:

And they were, uh, my daddy sold a lot stuff to the Hattaway Seed Company in Greensboro.

Michelle A. Francis:

What company's that?

Nell Cole Graves:

Hattaway Seed.

Michelle A. Francis:

Hattaway.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. They don't sell no more. And so, whenever he'd take the pots up there, well he'd take those little old frogs where I'd made and they'd buy those. And then whenever I got 13, somethin' like that, well he told me to start learnin' how to make bowls and things. So I started doin' that and he'd take one of those bowls up there and sell it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Huh. Well, how did you learn? Did you just learn by watchin'?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, I learned by watchin' and my daddy taught me how. He'd work, he'd center the clay for me, you know, so he'd get it real centered, and then I could make a nice little bowl. And then one day he told me he will not center no more. I was gonna learn to do it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were you scared about havin' to do it by yourself?

Nell Cole Graves:

No. If I tore one down it'd be all right.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) Did you have any idea it was gonna take so much work, makin' pots? That you'd be doin' it for the rest of your life? Did you know, ever have that feelin'?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, that would a'made me nervous, I guess. (Laughter) But I'd rather do it than anything else I ever did.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's what most people say that I've talked to. That they wouldn't change their job or quit makin' pots for anything in the world.

Nell Cole Graves:

No, no, no. No way. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you have your own special wheel?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

You must have been a lot smaller than the men.

Nell Cole Graves:

And my wheel was smaller.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was it? Who made it?

Nell Cole Graves:

Who made my wheel?

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Nell Cole Graves:

My daddy made the wheel and then we got, uh, the wheel for it from Biscoe, down there at Biscoe Foundries?

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Nell Cole Graves:

They made that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was it a kick wheel?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

That must have, you must have been pretty strong.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, I was strong. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Those kick wheels took some strength.

Nell Cole Graves:

I had a kick wheel until, uh, let's see, I guess it was 1930.

Michelle A. Francis:

1930?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's when you got an electric wheel?

Nell Cole Graves:

My daddy had a Delco that made lights. We didn't have electricity and he would, he had a what they call a Delco that made lights, electricity?

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Was that like a generator--the Delco?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. It had an old gasoline engine, you know, and he kept that thing goin'. And so he did that, rigged mine up to that.

Michelle A. Francis:

That must have been so much easier.

Nell Cole Graves:

It was easier. And then whenever we got electricity down here, he changed 'em all then to electric. But they couldn't change all of 'em then because the old thing wasn't strong enough to give us all that much.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, were you in school when you were doin', makin' the pots?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

What'd you do, come home?

Nell Cole Graves:

Come home. Just, see, our school, I had to walk to school and so whenever I'd get out of school then I'd rush to get home so I could get down here (Laughter) and make some more pots.

Michelle A. Francis:

You ,really did love it, didn't ya?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. I really didn't like school. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

You didn't?

Nell Cole Graves:

My mind wasn't at the school house, my mind was back here with my daddy.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) Were you and your dad real close?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Yeah, we sure were.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you ever take walks together or do things together, or did you mainly just work pots?

Nell Cole Graves:

We worked together, and then on Sunday, well we would walk maybe in the woods, and I'd look for little flowers and things like that with my daddy and mama.

Michelle A. Francis:

I bet that was fun. A special time.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

A special time on Sundays. Well I guess you were glad then when you got out of high school.

Nell Cole Graves:

I didn't go to high school.

Michelle A. Francis:

You didn't go to high school?

Nell Cole Graves:

No!

Michelle A. Francis:

Boy, you really didn't like school, did ya?

Nell Cole Graves:

No, I didn't! 'Cause I didn't want, I had to walk all the way to Seagrove--walk from here to Seagrove by myself, you know.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh my, that is a long way.

Nell Cole Graves:

Went back and forth to high school myself. I didn't want to and my mother, she didn't want me to go because, you know. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

The distance.

Nell Cole Graves:

My brother, Waymon, was a'workin' down here, and so I would a'had to gone by myself. So I didn't want to go back to school. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

So your little school that you went to, that you walked to down the road, what was the name of that school?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mount Zion.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mount Zion.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah (Laughter). That was about, uh I guess 'round three, four miles from here, three or four.

Michelle A. Francis:

That was a long walk.

Nell Cole Graves:

-Oh yeah. And through snow and everything.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, bad weather. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, bad weather's right. (Tape stops, then starts)

Nell Cole Graves:

. . .Mount Zion School. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

We surely were, talkin' about Mount Zion School. Was it a one-room school?

Nell Cole Graves:

Two.

Michelle A. Francis:

Two rooms?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was it a little frame building?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you have one teacher or two?

Nell Cole Graves:

Had two teachers.

Michelle A. Francis:

Two teachers?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well how did the grades go?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh, seven.

Michelle A. Francis:

Through the seventh grade?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. When you finished the seventh grade there you had to go down, you had to go to high school.

Michelle A. Francis:

How many people were in, children were in your class, in the school? Do you remember?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh, there'd be maybe uh, 30 or 40.

Michelle A. Francis:

So it was kind of small. I guess everybody knew everybody, didn't they?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, oh yeah. We all walked together. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

That's right. (Laughter) Did you like, did you like any of the subjects that you took in school? Or did you just not like 'em at all?

Nell Cole Graves:

Like what, the teachers?

Michelle A. Francis:

Any of your subjects, like reading.

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh. Yeah. I liked 'rithmetic and things like that. I didn't care anything for geography. I wasn't interested in that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. Well your arithmetic has helped you out here, hasn't it, tryin' to remember what all of these pots cost.

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) Yeah. One day she, uh, there was a little girl here this week, she said, I was figurin' up her mama's things, but, "Why don't you get you a calculator?" I said, "I have." She said, "Why don't you get you a addin' machine?" I said, "I have." And I just kept a'workin'. (Laughter) And her mama said, "Her calculator's right up there in her head."

Michelle A. Francis:

That's right! (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

I don't even know how to use calculators.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really, I don't think you need one. You keep all of these figures in your head just fine without 'em, seems to me. When you were makin' pots, about 13, who else was workin' here besides your brother, Waymon? Was it just you and he makin' pots?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh, just the three. Daddy, and my brother and myself. And then Mother would come down when we's puttin' a kiln of pottery in, and she would help us hand it to him. But she, she didn't like it.

Michelle A. Francis:

She didn't like it much?

Nell Cole Graves:

She didn't like the pottery business. She liked, I guess she liked the money that my daddy was gettin' (Laughter) but she didn't like the work.

Michelle A. Francis:

She didn't like the work. Huh. I guess she preferred to be a home-maker?

Nell Cole Graves:

Home-maker, yeah, in the garden.

Michelle A. Francis:

In the garden? Did she love gardening?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, and made me help her. I didn't like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

You didn't like that either. You wanted to be down here with your dad makin' pots. (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

Right, right, right. Right down here.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, what were you usin', a wood kiln then? Wood- burning kiln?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Oh yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

What kind of glazes did you have?

Nell Cole Graves:

Salt glazes.

Michelle A. Francis:

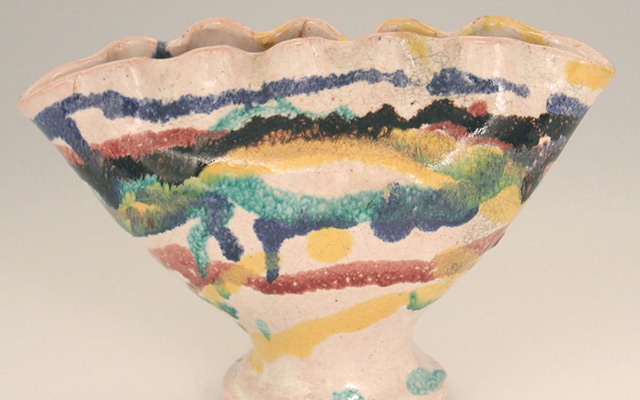

So you weren't makin' any colored glazes at that time?

Nell Cole Graves:

No, not like this, no.

Michelle A. Francis:

When did you start makin' the colored glazes?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, I don't know. I wouldn't know when started makin' 'em now. I'd have to study a'way back.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's all right. Who was your daddy sellin' pottery to? Did people come to the shop here?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh, a lot of people would come, and of course he sold it to the Greensboro, up there where the [unintelligible]. And a lot of people would come here from Pinehurst. They'd come from the North and Pinehurst and stay for the winter. Well, they got to knowin' about the pottery and they'd come up here and they'd get uh--we had a big old wooden barrels then that we would get at someplace. I don't know what they had in 'em now, but anyway, my daddy'd get those barrels and we would pack 'em full of pottery and ship 'em to 'em by train.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. What kind of shapes were you makin'? You mentioned bowls and. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

Bowls and then uh, he would uh, my daddy he'd make what they call milk crocks, too. And those big churns? And then

he got to makin' the jars, you know, it looked more like a jar than it would a churn. And then Waymon, he learned to make the large pieces then, too.

Michelle A. Francis:

You stayed mainly with the smaller ones though, didn't you?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

It takes, I guess, really strong arms to make. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

. . .to do those big ones.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. And a tall person, too. (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, my brother, he had to get on somethin', stand up on somethin' you know, when he gets to makin' those tall pieces.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah.

Nell Cole Graves:

A kind of block, you know, that they fix and stand up on.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, weren't you about the only woman?

Nell Cole Graves:

I was the first woman that ever made pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

The first. That must have gotten you a lot of attention.

Nell Cole Graves:

I know it. (Laughter) A lot of people liked me. They'd bring me candy, and I love candy, and I'd keep those--I still got some of those boxes that they brought candy in.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really?

Nell Cole Graves:

My mom and daddy got me a, they got me a pink trunk, a pink trunk for me to keep my junk in. Got Waymon a blue one. And I still got mine and I got a lot of things that people gave me when I was little.

Michelle A. Francis:

Huh. You ought to hang on to that.

Nell Cole Graves:

I know.

Michelle A. Francis:

Those are special.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Those are special things.

Nell Cole Graves:

It's in a special place (Laughter).

Michelle A. Francis:

So, what was the trunk like, how big would it have been?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh, I guess about uh, 26 inches.

Michelle A. Francis:

Sort of like a wheel barrow size?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh, yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

About the size of a wheel barrow. And yours was pink and Waymon's was blue?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mine was pink and Waymon's was blue.

Michelle A. Francis:

What else did they, did people bring you, besides candy?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh, they'd bring me, just little old tinkey things that you know, that they could buy in the stores. And then every time anybody'd give me anything, I'd go put it in that. And my sister-in-law, she uh, after my brother married, I was, I was about, I reckon I was about nine years old then. And she would make me things, you know, dresses and things. And the first thing she made me was that, what they called the "mini-suit" then. A little skirt and then a blouse.

Michelle A. Francis:

I bet that was pretty.

Nell Cole Graves:

And my brother, her husband, her and I, he was in the service, so they was gonna have a corn shuckin' at her father's place, and she made that little red mini-suit to go with her over there to the corn shuckin'. And then after they all had corn shuckin', they had music and they'd dance for about three or four hours.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, I bet that was fun.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

I bet you were proud to have that new outfit on.

Nell Cole Graves:

I was proud to have that dress. And this man come, I never will forget, he was big and tall, you know, and I was a little girl. And he come and asked me to dance with him, and I thought that was the stuff! (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

I still have that old mini-suit.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you really?

Nell Cole Graves:

And my sister-in-law's still livin'. She's 85. And so, I told her that I would bring it over there someday and let her see it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, you ought to.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, I don't think you, you must have a house-full of things that you've never thrown out.

Nell Cole Graves:

You should see my house. (Laughter) I got things, everything anybody give me, I put it away. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, you better label it all, so everybody knows what it is. (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

Don't have no more time to sort what I got. I don't have any children, so.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you still have some of the early pots that you made?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh, yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

What about the little frogs?

Nell Cole Graves:

I've got, still got one or two of them little old frogs that I made.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. And one lady, she had two and she brought 'em and gave 'em to me one time.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did she?

Nell Cole Graves:

And she gave me uh, an old piece that uh, you wouldn't know anything about stoneware that Henry Hancock made.

Michelle A. Francis:

I've heard of the name, though, Henry Hancock.

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, she brought me a, what they call a "butter crock" and then a lady gave me some old stoneware and one of those um, rocks, I mean what is it, tops, that she gave me was for that.

Michelle A. Francis:

The butter crock?

Nell Cole Graves:

Butter crock. And it fit right on it.

Michelle A. Francis:

You're kidding?

Nell Cole Graves:

And his name, Henry Hancock's name's on that, too.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really? Isn't it strange how that worked out?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. But the lady that gave me the crock, she didn't know what happened to the lid. It was her mother's and she

said she wanted me to have it. And she gave me a piece of pottery that my brother made. It, well we called it a "wine jug" then. It's got a long goose neck to it. And a handle on that neck that you could pour with.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was that salt glaze?

Nell Cole Graves:

No, hu-uh. That was in the turquoise blue. My daddy was makin' that, too. And so she gave me that. That was given to her for a wedding present by my brother-in-law. And, no my daddy, my daddy gave her that. And so she gave it to me to keep.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well that was nice of her to do that.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. Course, she doesn't have any children, and she said she wanted me to have it.

Michelle A. Francis:

She knew you'd appreciate havin' it.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. And I thought, well, when we get our museum in Seagrove, all of my stuff will go in there.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. That'll be a good place to put it.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Yeah, because I don't want it to be out somewhere where somebody'll sell it.

Michelle A. Francis:

No, hm-um. It should be, it should stay together.

Nell Cole Graves:

I just want it just right there.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. It should stay together and here in Seagrove.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, that's where we need a museum, in Seagrove. But, Dorothy wanted to sell hers and so I don't blame her for it. Her son's not interested in it.

Michelle A. Francis:

No.

Nell Cole Graves:

Not one bit.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well she did sell it as a collection, so it will stay together.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. It will stay together. That's right. (Tape stops, then starts)

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you have a favorite shape when you were makin' pottery?

Nell Cole Graves:

I guess those little baskets.

Michelle A. Francis:

Those little baskets?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. With the little handle across the top, and little flutes on the sides. I think that was my favorite.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you still make that shape down here?

Nell Cole Graves:

I still make 'em, yeah. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

I haven't seen any in the shop, I don't think in a long time.

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, I still make 'em. But, I don't have any in stock now. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Didn't sell it to Dorothy, did ya? (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

No! (Laughter) That was a cute little candle holder.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was it?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. It was like that, the pewter one.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Nell Cole Graves:

I made the pewter one. But hers was a little tiny one like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Like that one?

Nell Cole Graves:

It was cute. It was cute as it could be.

Michelle A. Francis:

I bet you that person didn't get it. I bet Dorothy kept that one.

Nell Cole Graves:

I doubt it. I bet Dorothy's got that sittin' right in her house.

Michelle A. Francis:

Uh-huh. (Laughter) Well, I can't blame her. I'd probably do the same thing. (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

Maybe I better go up there this weekend and check on it. (Laughter) Oh, Dorothy's lookin' good.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is she?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

Good. I'd heard that she was doin' real well.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. She is. She's gainin' weight. She says, "Every piece of every bite I take turns to fat."

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) Well, that's all right.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, what other shapes were you makin' besides the little baskets and bowls?

Nell Cole Graves:

And candle holders?

Michelle A. Francis:

And candle holders.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. And, uh, well, at one time I made all the casseroles and pie plates.

Michelle A. Francis:

Goodness.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. That was uh, in, in the '60s. I made all of 'em up until '64. Then I had to go and have an operation. And then Virginia came and she started makin' 'em for me.

Michelle A. Francis:

For a long time there was just you and Waymon and your dad.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

When did your dad die?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh, my daddy died in 1934.

Michelle A. Francis:

'34?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was it just you and Waymon then, makin' pots?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh, our brother-in-law, Bascome King, was workin' here, when my daddy died.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Was that Virginia's. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

Virginia's father.

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .father.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

So he was makin' pots, too?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. And then, after he quit us later on, and put him up a pottery of his own, Bascome did.

Michelle A. Francis:

He did?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. And so Virginia helped him until he died.

Michelle A. Francis:

Where was that pottery?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh, over here at Asbury. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Asbury, again. (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, Asbury again. But that was known then as Steeds. The post office was Steeds. It was, it's just about four miles from here, three or four miles, across 220.

Michelle A. Francis:

In 1934 then, when your dad died, were you all still doin' just salt glaze?

Nell Cole Graves:

No, we were doin' slip colors then, and turquoise and the greens and the blues.

Michelle A. Francis:

In a, was it a wood-fired kiln still?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. Wood-fired. We had a wood-fire until Waymon and I were bought all the children out because they wasn't interested in the pottery. So we bought the children's part out, and then we put in, uh, gas kilns--well, kerosene. It'd be an oil kiln instead of gas.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. How many brothers and, were you the only girl?

Nell Cole Graves:

I have one sister.

Michelle A. Francis:

Tell me who your brothers and sisters were.

Nell Cole Graves:

I had one sister and I had, uh. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

What was her name?

Nell Cole Graves:

Vellie, Vellie King.

Michelle A. Francis:

Vellie?

Nell Cole Graves:

Vellie, V-E-L-L-I-E. And named me Nellie, N-E-L-L-I-E. I don't, but my daddy named me. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Did he?

Nell Cole Graves:

Named me Nellie Lennia, after one of my cousins that he thought so much of, one of his nieces.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's, is that one word, Nellena?

Nell Cole Graves:

Nellie. Uh-uh. Lennia was my middle name.

Michelle A. Francis:

Lennia? How do you spell that?

Nell Cole Graves:

Lennia, L-E-N-N-I-A, Lennia.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's pretty.

Nell Cole Graves:

Nellie Lennia. (Laughter)[unintelligible]. And so then we got a cousin from Sanford, no Carthage, we got a cousin from Carthage to come and help us make pottery, after my brother-. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Who was that?

Nell Cole Graves:

His name was Luck, Ad Luck. And then whenever, I don't remember what year he died, but he died, and then uh, Waymon and I been makin' it since then.

Michelle A. Francis:

Since then. And then Virginia came though.

Nell Cole Graves:

Virginia came back in '64 and helped.

Michelle A. Francis:

'64.

Nell Cole Graves:

See, I had to have an operation and I knew that I'd never be able to pull up the clay like that. But I made all the pie plates and casseroles, and when we was buildin' this block buildin' up here, I was, I had to move my wheel down here. And I was makin' casseroles and pie plates in the basement here. And a colored girl was helpin' me carry 'em all the way to the dry house.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh my.

Nell Cole Graves:

And she'd get so far behind she'd cry.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) You were makin' 'em that fast, huh?

Nell Cole Graves:

I was makin' 'em that fast, and she'd get so far behind. She was workin' clay for me, too.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh my. You were keepin' her busy, weren't ya?

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) I was hard up on her.

Michelle A. Francis:

How many, how many casseroles would you make in a day?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh Lord, I don't remember that.

Michelle A. Francis:

A hundred?

Nell Cole Graves:

Maybe, yeah. I'd make a hundred casseroles in one day if I was makin' casseroles all day. Maybe 150 pie plates, or 200.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh my.

Nell Cole Graves:

'Cause pie plates, you can throw them out pretty fast.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. One of the things that Cole's pottery today-and

probably a long time ago, too--is everybody talks about it is how thin. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Our father taught us how to make it thin. He wouldn't let us leave it thick. He hated it. He'd make us pull the clay out.

Michelle A. Francis:

That must have taken a lot of practice to be able to do that without, you know, getting it off center and. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

It did. Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .and breaking.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. I know it. If he, if we didn't make a piece pretty, we didn't get to keep it. I mean, if we slopped on up, we didn't get to keep that.

Michelle A. Francis:

He'd make you start over.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Start, over. And he taught us that, whenever we made it, to make it thin--to come up there and thin it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Well, did you teach Virginia? 'Cause she makes 'em thin, too.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh, Virginia, she learned over here, while her father was a'makin', she'd be on the wheel tryin'.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. So she must have started when she was young, too.

Nell Cole Graves:

She did. She started when she was young. She was workin' clay for her daddy, over here, and weighin' it out and all. And then she would get on the wheel and try to make a piece. And then she started, she learned quick.

Michelle A. Francis:

Back to the different kinds of glazes that you had in, when it was done in a wood-fired kiln.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

That makes such a different-lookin' glaze.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. I know it does.

Michelle A. Francis:

It's pretty. It's a lot um, in some ways it's sort of softer-looking, the glaze is.

Nell Cole Graves:

Now our turquoise, people will keep sayin', "Well, I got a turquoise piece." Says, "It looks somethin' similar to what we've got now." But says, "It's not exactly." Well, it's a wood-fired pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Yeah. Just has a whole different look about it. I like it. I like your pottery today, too.

Nell Cole Graves:

I know, but I like that other.

Michelle A. Francis:

But, yeah. There's somethin' about that glaze in a wood-fired kiln that just. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. And then we had a yellow then, and it, it looks different.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. And our white looks different. I have a white vase that I was up there glazin'. (Tape stops, then starts)

Michelle A. Francis:

Because you were the first woman potter, and you could, I know I've seen lots of newspaper articles--I saw some of that film, someone took of you, when you were real young.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did all that make you nervous?

Nell Cole Graves:

Huh-uh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Havin' those people come and takin' your pictures and everything?

Nell Cole Graves:

No.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you ever have a feeling of being really special because you're the only woman?

Nell Cole Graves:

No. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Just everyday stuff to you?

Nell Cole Graves:

Everyday stuff. Right. (Laughter) I didn't ever think anything about it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Huh.

Nell Cole Graves:

And they'd say, "Oh, aren't you proud that you're the only one?" I'd say, "It's all right with me." I, you know, I just didn't care, I didn't say nothin' about it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Uh-huh.

Nell Cole Graves:

All work. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

But I bet your daddy was proud of you.

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh he probably was. But, he never did show it or

anything, to make me think that I was "Miss It". (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

I know what we were talkin' about, we were talkin' about all the kids in your family. And you were sayin', you were tellin' me about your sister. And we got to talkin' about how you had your cousin come up to help you.

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh yeah. Our cousin from Carthage, Ad Luck.

Michelle A. Francis:

Ad Luck. Mm-hum. But then I was gonna ask you about your brothers, your other brothers, besides Waymon.

Nell Cole Graves:

I had, well I had three brothers. One died whenever he was eight months old. And then I had Helton.

Michelle A. Francis:

Helton?

Nell Cole Graves:

Helton, H-E-L-T-0-N. And he, he wasn't interested in pottery. He, well, he had already married and gone away by the time my daddy got the pottery goin' good. And so my oldest brother, he wasn't interested in it. He was a sawmill man. So my daddy worked with him in the sawmill.

Michelle A. Francis:

What was his name?

Nell Cole Graves:

His name was Hermon.

Michelle A. Francis:

Herman?

Nell Cole Graves:

Hermon, H-E-R-M-0-N. And so then he had to go in the service. And when he came back he still was wantin' to be a sawmill person. But then he got tired of that later on and wanted to be workin' with pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. So he had a pottery in Smithfield.

Michelle A. Francis:

In Smithfield?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. And so, then later on he sold his pottery out in Smithfield and he came back--he retired, then he came back up here.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did he, so he never really worked with you and Waymon?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-uh, no.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you have any of his pieces?

Nell Cole Graves:

Any what?

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you have any of his pottery?

Nell Cole Graves:

My brother's pottery, where they made in Smithfield? Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

What did he, what was the name of his pottery?

Nell Cole Graves:

It was Smithfield Pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

Smithfield Pottery! (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

When was this? Do you remember?

Nell Cole Graves:

That was in, '16. Wait a minute. That was in uh, '29, '30.

Michelle A. Francis:

1929 and '30?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

So it was before your dad died.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

That he was down there. You said that your other brother wasn't interested in pottery.

Nell Cole Graves:

He was a mechanic.

Michelle A. Francis:

A mechanic.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Worked for the White Motor Company in Charlotte.

Michelle A. Francis:

And he'd left before your dad's pottery really got started.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, what did your dad do before? I thought he was always in pottery.

Nell Cole Graves:

He was always in the pottery, but then he, whenever we children got a little bit of age and old enough to do anything, well, he quit the pottery. See, he'd have to walk for miles to make pottery. And then he made for the people in, up in the mountains, the Hilton, Hilton's Pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

Your dad did?

Nell Cole Graves:

My daddy did. But he'd go up there and stay, but that was before my day.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. Well I didn't realize that he did that. I always thought he was here.

Nell Cole Graves:

He worked, uh, for his daddy until he died, in the pottery business.

Michelle A. Francis:

Till your granddaddy died?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

When was that? Was that before you were born?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh yeah. Way before I was born.

Michelle A. Francis:

And then he went up to work for the Hiltons?

Nell Cole Graves:

As far as I know, from then on he worked for the Hiltons. And then, uh, wait a minute, he worked for a place up here right before I was born. I don't know much about that. But he worked up here where you turn to come down off of old 220, you know to come down this.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Nell Cole Graves:

It was a man and his name was John Metty Yow.

Michelle A. Francis:

John . . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

John Metty. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Metty?

Nell Cole Graves:

John Metty Yow. He worked for him and they made churns and everything. But I don't know what year that was or anything. I wish now that I had all the history.

Michelle A. Francis:

I bet.

Nell Cole Graves:

But, I don't have, and it's no use to worry about it now.

Michelle A. Francis:

No.

Nell Cole Graves:

I can't it (Laughter), but I'd liked to have had it, and had the whole history. Course he walked to work there and he then walked to work for, uh, let's see, his name was Chrisco, John Chrisco.

Michelle A. Francis:

Heard of the Chriscos.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. He worked for John Chrisco. He walked for I don't know how many miles. You know where Harwood Graves lives?

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah.

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, it was back there. It was just before you went down to the. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

So he would have walked from here? This was still the home place?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Back then?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's a long ways.

Nell Cole Graves:

He'd walk back and forth to work.

Michelle A. Francis:

This must have been when he was a young man?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. He was a young man then. But they lived up here. But that was way before I was born.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, your dad really had it in his blood then, too, didn't he?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh yeah. My daddy had it in his blood. Well, did you ever get a--this is the Cole history. You don't have one of those books. [note].

Michelle A. Francis:

Is this the first one?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

I don't have the first one, I've got the second one.

Nell Cole Graves:

This is the Cole's history and you can have that one.

Michelle A. Francis:

Can I have that? Thank you, Nell. I appreciate that. So here is, is that your dad?

Nell Cole Graves:

Jayson?

Michelle A. Francis:

Jayson?

Nell Cole Graves:

Jayson D. Cole.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, did they spell his name right?

Nell Cole Graves:

What, how did they spell it?

Michelle A. Francis:

J-A-S-0-N. I thought you said it was J-A-Y.

Nell Cole Graves:

J-A-Y, I believe was. You can put J-A-S-0-N, because it's in there. That's the way they probably spelled it.

Michelle A. Francis:

It seems like I've heard of Ruffin before.

Nell Cole Graves:

Ruffin Cole was my daddy's brother and you know the Coles down at Sanford?

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Nell Cole Graves:

That was their grandfather.

Michelle A. Francis:

Their grandfather.

Nell Cole Graves:

Arthur.

Michelle A. Francis:

Arthur?

Nell Cole Graves:

Arthur Cole's children.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay. Now which Cole was it that went off, took a wagon load of pottery. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

That was my father, uh, I mean, uh, it was my grandfather, my daddy's father.

Michelle A. Francis:

Evan? Was it Evan that took it off and went down towards. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

It's uh, Hamlet, down in there, somewhere way down in there.

Michelle A. Francis:

And he died, didn't he? And they didn't even know he was dead for a long time, the family.

Nell Cole Graves:

No. See, they didn't have nothin', no way of gettin' anything back here. And they had to go down, whenever they found out, they had to go get his uh, team, and he had it in a covered wagon, you see. And they had to go get the horses and mules and whatever that was there. And then we tried to find his grave. We were gonna bring him back up here, but nobody ever, we never could find out anybody that knew anything.

Michelle A. Francis:

Huh. You'd think there would have been somebody that would have re--since he was a stranger, you'd think people would have talked about the stranger that came in.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. That "peddler" as they called 'em.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's right. It's strange that they didn't.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. We tried to find him, but we never could. So we had to give up.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, did your dad ever take wagon loads off to sell.

Nell Cole Graves:

No, I don't think my daddy did. If he did, he did for other people, you know. But I don't think he did. I think he made pottery more than he did anything like that. The

only thing my daddy would do, after we got to makin' a lot of pottery here, he would take a truck load to a shop in Arizona and then in Florida, Miami, he'd take a truck load of pottery down there.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's a long ways to go.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. He'd have one of the boys that worked for us to drive.

Michelle A. Francis:

How did people find out about you, those far-off people.

Nell Cole Graves:

Probably the northern people had it, you see, and then they just, word of mouth.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. What kind of pottery did you send down?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh most of it was large jars and flower pots and things like that that they used. And in Arizona it was about the same thing. .

Michelle A. Francis:

I guess they used it out in the garden as decorative gardenware.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was it glazed pottery?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh, glazed pottery. We had what we called, it was a red then, but we don't make it anymore because we used red lead in it to make it pretty. It was a red-orange it looked, and we had a, somebody brought a magazine up here that was from Florida and we were lookin' through it and found one of the pieces that Waymon made sittin' on the porch there of this building.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really? Huh.

Nell Cole Graves:

One of our pieces of pottery that my daddy, he carried it down there with the truck.

Michelle A. Francis:

That must have been a funny sensation.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. I could hardly wait for him to get back because he'd always bring us oranges and grapefruit and tangeloes.

Michelle A. Francis:

Treats.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Waymon told me at one time, I think it was Waymon that was tellin' me, that for a while there you made lots of lamps.

Nell Cole Graves:

We made lamps for the uh, the Dayson Lamp Company in Philadelphia.

Michelle A. Francis:

The what, what's the name of the company?

Nell Cole Graves:

It was Dayson.

Michelle A. Francis:

Dayson?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. We made lamps for them for several years.

Michelle A. Francis:

Waymon made the comment that he just got tired of makin' lamps, y'all made so many.

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, we made so many lamps, you know, to sell to them. My husband made up more than Waymon did, really. He made more lamps than Waymon did, my husband did.

Michelle A. Francis:

When did you and Mr. Graves get married?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh, 19--1930. 1930.

Michelle A. Francis:

And what was his first name?

Nell Cole Graves:

Hm?

Michelle A. Francis:

What was your husband's first name?

Nell Cole Graves:

Philmore.

Michelle A. Francis:

Philmore.

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) Yeah. Philmore Graves.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you spell that with an "F", F-I-L-L?

Nell Cole Graves:

Hm-um.

Michelle A. Francis:

"Ph"?

Nell Cole Graves:

P-H-I-L-M-0-R-E, Philmore.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did he grow up makin' pottery?

Nell Cole Graves:

Hm-um. He didn't make pottery, he didn't know anything about makin' pottery until after he married me.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really?

Nell Cole Graves:

Hu-uh. Well, whenever he started datin' me, he started. Before we married, he was workin' here for my daddy.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Doin' what?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh, well, he'd been glazin' and just work that we had to do with the clay, you know. We didn't have much machinery then you know, more hand work.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. I bet. Lots of hand work.

Nell Cole Graves:

Hard work, too.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you grind all your glazes? Or did you buy 'em?

Nell Cole Graves:

We bought 'em, most of 'em anyway. We had to buy our own fret and stuff 1ike that then. But we make our own now, you know, with our fret machine we do our own glazes.

Michelle A. Francis:

Where did you buy your glazes from?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh, Drakefield.

Michelle A. Francis:

Drakefield?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. Drakefield, D.F. Drakefield.

Michelle A. Francis:

Where's that?

Nell Cole Graves:

In New York.

Michelle A. Francis:

New York?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you have to sort of modify the glazes? I mean, did they know that you were usin' a wood-burning kiln?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

They worked fine, you didn't have to. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

They worked fine.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's kind of unusual, isn't it?

Nell Cole Graves:

I know it. Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

Because the clay probably would have been different down here.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. But it worked good. Didn't have no trouble with it at all.

Michelle A. Francis:

Huh. Where did you get the clay?

Nell Cole Graves:

Where did we get the clay?

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum, your clay?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, when I first started here, my daddy had it on, some clay on this land. And then, he used it, and then he got clay between here and Asheboro. They called it the clay, the Auman Clay Pond. And then they decided to sell it to the terracotta people in Greensboro and get their money all at one time. And so, then's whenever we had to find clay at Smithfield.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is this stoneware or earthenware?

Nell Cole Graves:

It was stoneware. And my daddy and my oldest brother, well my daddy had an uncle that, Henry Hancock, the one I told you about the butter crock. And he had made pottery down there years before my daddy went down there. So, he decided that they'd go down there and see if they could find out where he got the clay and such pretty stoneware. And he found where he got the clay and everything, and this man had taken him, this old man was still, he was a young boy when Henry Hancock worked there, and he was still livin' and so he taken my daddy down there and showed him where he got the clay and everything.

Michelle A. Francis:

And that's how you ended up gettin' that clay.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Where'd you get your earthenware?

Nell Cole Graves:

You mean?

Michelle A. Francis:

The red clay.

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh, the red clay. Well, we can get that in Smithfield, too.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did ya?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. We got, there's a gray and there's a kind of, what makes orange.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. That things lasted a long time, hadn't it?

Nell Cole Graves:

Oh yeah. (Laughter) There's a lot of clay down there.

Michelle A. Francis:

So do you still bring it back here?

Nell Cole Graves:

From Smithfield? Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

And let it dry out under that shed?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. That shed, all that [unintelligible]

Michelle A. Francis:

Who works it up for you, you know, grinds it?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, we got a, we got a big ball mill that you just put water in it and put your clay in there and it beats it and then we run it from that in the sack and then you put the pressure on it and the water all comes out and leaves your sack full of all your clay. And then we run it through a pug mill to bring it in here.

Michelle A. Francis:

Bring it in here. That sure beats doin' it by hand like you used to.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. I know.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you all ever have one of those old-time pug mills that the mule. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

Huh-uh. They have that at Jugtown.

Michelle A. Francis:

Uh-huh. I've seen pictures of that.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. They had it at Jugtown, but we never had it.

Michelle A. Francis:

How did you used to do it before you had all that equipment?

Nell Cole Graves:

We had, my daddy had an old tractor, a real old tractor. And he hooked it up to a, well it was a pug mill, I guess they call 'em now. But it was a regular old brick mill where they used to run brick out. And he bought that from some company that quit makin' brick.

Michelle A. Francis:

So he hooked it up to the tractor.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Hooked it up to the tractor and that's how we could run it out.

Michelle A. Francis:

That worked pretty good, too, I reckon. (Begin Side 2)

Michelle A. Francis:

What's the story that Waymon likes to tell about the horse thieves?

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) I'm not gonna tell you about that!

Michelle A. Francis:

But, you can tell me that it's not true. (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

He makes out like, he tells about, we have horse, said they even had horse thieves in our family. (Laughter) But it's not true, he just tells it to get a big laugh.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) Waymon likes to laugh, doesn't he?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. He tells a whole lot of wild stuff, 'bout liquor jugs and all 1ike that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you make some liquor jugs though?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, my daddy made liquor jugs from stoneware. But, you see, the bootlegger would buy 'em and put their booze in 'em. [unintelligible] I don't know, I haven't seen liquor, but they had it somewhere where, they would run out somewhere and they'd run it in those jugs and I guess maybe they aged it in there, I don't know.

Michelle A. Francis:

I don't know. Probably, well. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did they age moonshine? I always had this feeling they just drank as soon as they could get it! (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

I guess maybe they, they probably aged it, maybe it had more kick to it, I don't know.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, they probably made brandy around here, too, didn't they? Homemade brandy?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

Peach brandy or somethin'?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well you make that with uh, I think you make that with a liquor still, too.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you?

Nell Cole Graves:

I think so.

Michelle A. Francis:

I don't know anything about makin' it.

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) I never did make it, but, I've heard 'em talk about runnin' brandy out, things like that. I figured it come out about the same thing as the ones that had corn liquor.

Michelle A. Francis:

Nell, was it hard durin' the Depression, bein' in the pottery business?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, yeah. Because sometimes we didn't have any orders or anything like that. But we still made pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did ya?

Nell Cole Graves:

We'd keep makin' pottery. Stackin' it up.

Michelle A. Francis:

I guess 'cause you were probably makin' salt glaze then, weren't ya?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. We made a salt glaze then and made, and used it for churns and things like that. And then my daddy, we

had the farm here, too. And we uh, had our own things we had to eat out of the garden, and all that. And then we had, wherever we would have, have to go and get flour for bread, all they had to do was just go and sack up some wheat and take it to the mill. And they would grind it for us. So much uh, tollage, I think they called it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. "Tollage"?

Nell Cole Graves:

Rent, no it wouldn't be rent. They'd give 'em so much wheat to grind it. They'd take out some of it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, okay. Yeah, I know what you mean.

Nell Cole Graves:

They'd take some out.

Michelle A. Francis:

Sort of take out their labor in wheat.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. And, so we did, and we had our own hogs, calves, and whenever we needed beef, we'd go kill a cow.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, you and Philmore were married then, during that time weren't ya?

Nell Cole Graves:

In that time we were married, yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. Did it take him long to learn how to turn?

Nell Cole Graves:

No, huh-uh. My dad always said he was, he was, he learned quick, really did. He was a good pottery-maker.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was he? Did he have a specialty?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. Well he made, uh, he would any of the shapes and make 'em, but uh, and the lamps and all, he made beautiful lamps. And he made pretty vases and things like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did he?

Nell Cole Graves:

A lot of his shapes are out there now. That shape right there was his.

Michelle A. Francis:

This one?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. Now Waymon makes it. I told him a while back that we sure needed 'em.

Michelle A. Francis:

They haven't, this is, you haven't been makin' this very long, this shape, have you? Recently?

Nell Cole Graves:

Not, not lately. Because Phil made it you see, and we just never have started runnin' 'em out.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is it one that he made up himself? Did he figure out this shape himself?

Nell Cole Graves:

No, I guess maybe somebody brought a drawing or something like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

It's pretty the way it comes up and the handle curves around. It's real graceful.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. He was a good pottery-maker. One of the best.

Michelle A. Francis:

Sounds like you. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

What I mean, if he didn't, if he'd made a piece and if he didn't like it, if it didn't look all right, he would tear it up.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Nell Cole Graves:

He wouldn't let go out like that. That's how he worked with a piece, you see. But he'd tear it up. He was a good pottery-maker. And he made all the mugs and the sugars and creamers and all of those shapes there. This was before Virginia learned how.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah.

Nell Cole Graves:

She helped her daddy in the pottery as long as he lived. And then, uh, then she came back and worked with us.

Michelle A. Francis:

Virginia, when did she, was she makin' pottery in the '30s?

Nell Cole Graves:

In the '30s? Uh-uh.

Michelle A. Francis:

She would have been, I don't know how old Virginia is.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-uh. No.

Michelle A. Francis:

But she would have been real little then wouldn't she?

Nell Cole Graves:

She was young, no, she wasn't makin' pottery. She's uh, she's not but about 10 years younger than I am--10, 11. 'Cause whenever they's born, don't put this on there.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

My mama, whenever Virginia and them was born, and my mama would go over there and I wondered why she was goin' over there so much. And so, then, it was their little baby. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

That's what I figured out, what it's all about. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

What it was. Were you the youngest in your family?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Ah.

Nell Cole Graves:

They didn't think they was gonna have any more. (Laughter) Then come me.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well I bet that's another reason why your daddy liked you so much and why you were a favorite. You were the last one. The baby in the family.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. And you know, I'd go with him to the field whenever he'd be a'plowin' or anything. I would sit out there in the field with him. And I'd try to walk in his footsteps, you know, and he was tall and long-legged like I am, like my legs are now. I'd try my best to put my foot in his footsteps. I could never reach. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Did your dad like farmin'?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. He liked farmin', too.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did he?

Nell Cole Graves:

We had to, you know, to make. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah, everybody did back then, didn't they?

Nell Cole Graves:

Everybody did farmin' down here. Make your own [unintelligible]. Corn things for the hogs. This lady broke her lamp.

Michelle A. Francis:

She did?

Nell Cole Graves:

And she wanted one just like it. And it really broke when it broke (Laughter). I told her that I'd take it up to see if we could make one. Her husband said, "Go buy you another one. Don't fool with that one." She said, "I can't buy another one." That was, that was a old lamp, old shape. We didn't make it, but, I don't know from who she got it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is Waymon gonna try and copy it?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. I told him I'd put it together for him. I need to get the tape and patch it up. I'll work on it of an evening when everybody's gone.

Michelle A. Francis:

Virginia's son Mitchell's makin' a lot of pottery now, isn't he?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. He makes uh, a lot, all the pie plates and

all the luncheon-size plates and the bread and butter plates.

Michelle A. Francis:

Bread and butter plates.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. He makes all those.

Michelle A. Francis:

Some of the big bowls, does he make them?

Nell Cole Graves:

He makes all these different punch bowls and things now--bread bowls, salad bowls. He's good. He's gonna be a good pottery-maker.

Michelle A. Francis:

It's nice that he's gonna stay in the business.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

And keep it goin'.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, I know it. I hope they do. (Sigh)

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, I can't imagine there not bein' a Cole's Pottery.

Nell Cole Graves:

No. That would really make you turn over in your grave.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) One of your dad's brothers was Charlie Cole, wasn't it?

Nell Cole Graves:

That was, uh, he wasn't my daddy's brother.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was he cousin?

Nell Cole Graves:

Charlie was my daddy's nephew.

Michelle A. Francis:

Nephew!

Nell Cole Graves:

He was Rufus, I mean Ruffin, Ruffin Cole's son, Charlie was.

Michelle A. Francis:

Ruffin was. Charlie, okay. (Tape stops, then starts)

Michelle A. Francis:

What shapes do you make mostly now, Nell, when you get a chance to do it?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh, goblets and wine. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Like these little goblets here?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. And then I make a larger one like this. A tea goblet and I make the little baskets and pansy bowls.

Michelle A. Francis:

What's a pansy bowl look like?

Nell Cole Graves:

See if I got one. (Tape stops, then starts)

Michelle A. Francis:

This might be good to have on the tape about the, about Mrs. Busbee's hat. You remember her wearin' that straw hat?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. I remember wearin' that straw hat. And they would, had a little mule and a one-horse wagon and she'd be a'sittin' down in the flat in that wagon. I remember them a'comin' up here to see my daddy.

Michelle A. Francis:

Would they just come to visit, or would they. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, they'd just come to visit and then they'd ask him things about pottery or somethin' like that. That's whenever they were gettin' started.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did they ever try and get him to work for them?

Nell Cole Graves:

No, huh-uh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Melvin worked for them for a while.

Nell Cole Graves:

Ben. Ben Owens did.

Michelle A. Francis:

And Ben, and Ben.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Ben was their regular. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

He was their regular potter, wasn't he?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. And then Charlie, Charlie. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Craven?

Nell Cole Graves:

Huh-uh. Charlie Owens, no. Charlie Teague!

Michelle A. Francis:

Charlie Teague.

Nell Cole Graves:

Charlie Teague made pottery for them. I've got a piece of pottery that Charlie Teague made there and he, he wanted me to have it and I, I still got it. My mama used it to put her buttons in, whenever she'd have buttons come off a shirt, you know, she'd have extra buttons.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. She'd put it in that?

Nell Cole Graves:

She'd put 'em in that. If a button came off she'd sew it back on another shirt. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. You've got quite a museum don't ya, just in your house?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Just of things people have given you?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. My daddy gave me a, a big J. D. Craven jar. When I got married, he bought a big Craven jar stands up about like this.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh my!

Nell Cole Graves:

It's got a lid on it.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's about two, two and a half feet.

Nell Cole Graves:

'Bout two and a half feet high. And it's got a lid on it. Looks like they've used for pickles or something.

Michelle A. Francis:

For pickles.

Nell Cole Graves:

My daddy bought that and gave it to me, from some sale that they had, a sale. And he bought that and gave it to me.

Michelle A. Francis:

Wow. And you still got it?

Nell Cole Graves:

You're not kiddin'! (Laughter) It's locked up.

Michelle A. Francis:

I hope so.

Nell Cole Graves:

And that will go in our museum whenever we get it built.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah.

Nell Cole Graves:

With all the bars in around it. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, you'll want to have good security.

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, we'll have to have.

Michelle A. Francis:

And fireproofed.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

You want to have it fireproofed.

Nell Cole Graves:

Fireproofed and everything, yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

What stage is the museum in right now?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, we're just still collectin' money. I mean gettin', keepin' our money and all. And, we're, we're workin'.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you have, you've got some land, right? Or did you decide not. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

We'd got the land bought, but the man has promised to sell it. I told him that, if he just let--there's one place we wanted, but the boy's askin' too much for it. And, gonna have to be a lot of work done. We'll have to take an old house down and everything like that. And another place I'd like to buy if we can just get it from this man, there in town. (Tape stops, then starts)

Michelle A. Francis:

I wanted to ask you, Nell,,what is it about pottery that you like the most?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well really, I like to make pottery more than I do anything else. And I love to glaze. And I love to sell pottery because I just love people. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. (Laughter) You like just about all of it!

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, I like it all. There's not anything about pottery that I hate. Lot of people say, "Well, I wouldn't wait on people like you do for nothin' in the world." But I love it because I like people and you know, we have a good time in here, just laughin', cuttin' up like we did today.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's right, I enjoy it.

Nell Cole Graves:

And nothin's serious or anything and won't speak or any of that. Shoot, they gonna have to speak to me (Laughter) or else they leave.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, do you miss not getting to make pots as much?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. I do. I miss it because sometimes I go and maybe make, maybe 30 minutes and I think well, maybe won't nobody come right now for a while and I can make more wire glasses or tea glasses, and then there's somebody to drive up just about that time. And I have to quit and then if I can get to go back, I make a few more. That's the only way I can get any.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. Had you ever thought about puttin' a wheel right in here?

Nell Cole Graves:

I did. I thought about it. But the children mess it so bad.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do they?

Nell Cole Graves:

They'd be over here all tryin' to run the wheel all the time and there'd be clay all over every place.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah, that wouldn't work.

Nell Cole Graves:

Huh-uh, that wouldn't work. Unless I put it in the basement and locked the door.

Michelle A. Francis:

But then they'd. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

Then if they go down there they all want to go to that basement, and fumblin' around in it. And then they'd be messin' with the stuff.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. And it'd still be hard to wait on people, too.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum, mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Be here to answer their questions and all that.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

You just need somebody to help you.

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) I don't know where I'd get 'em. You know, you got to be nice to customers. You can't just walk by 'em and not speak or ask 'em if I can help 'em or somethin' like that, and talk to 'em. You just can't do people like that. And they won't want to come back.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's right.

Nell Cole Graves:

They'll say, "Well, they're just not kind." Or, "They just treat you like you're nothin'." Stuff like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Well, you have so many people that come from out of town, you know, out of this area. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Oh yeah. Out of the state and everywhere else.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's right. And so it's a trip, it's an event just to come down here.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. I know it. And if they. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .if they don't have a good time. . .

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) If they don't have a good time, it's just too bad. They all expect to be a'hollarin' and laugh and talk. When I fell, uh, I was goin' out to the kiln shop one night, and there's some roots had growed up, up off the, inside up on the ground, on top, and I stumbled and fell on one of those. And I hit my head and my nose (Laughter). Well the next day, that night I looked terrible, but the next day I looked bad. And then from then on, I went to the doctor and he said "You've got this for about four weeks." But I had it for about six weeks. And I had these circles around my eyes. I looked like a coon. (Laughter) People had more fun over that!

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, I bet they did!

Nell Cole Graves:

They'd just laugh and holler at me. And one man called me from Greensboro and asked me if, said, "Do you still look like a coon?" And I said, "I sure do!" (Laughter) They had more fun over that than anything else could a'happened.

Michelle A. Francis:

I'm noticin' the shelf area right behind ya there has got all kinds of pottery and dishes and notes and paper on it (Laughter).

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) And some of those orders will never be filled. But I still leave 'em hangin'. Some of 'em may be 15 years old.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh my! (Laughter) You've even got 'em tacked up on the wall back over there. I'd take you a week to get to it. (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

They'll say, "Will you take my order?" And I just write it down and I take it but, . . .

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .but that's as far as it goes?

Nell Cole Graves:

Some of it, uh, I won't never get filled, I don't think.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. Is this special stuff that they want?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. And it's maybe a plate in a certain color, you know. And a lot of 'em, I've got 'em stuck under here, but, whenever they ask for 'em, they've got a find out which one it is. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Whew! What are the dishes for? Are those. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

Those?

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. All these dishes.

Nell Cole Graves:

Lot of people, now this one has a bad place on it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Uh-huh.

Nell Cole Graves:

Got to go back in the kiln. But a lot of people, maybe call me and tell me to hold 'em a certain thing. That they've got a set and they've got some broken pieces. And I just stick 'em back over there until they come by.

Michelle A. Francis:

You been waitin' 15 years for some of them? (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) I have!

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, my goodness.

Nell Cole Graves:

Long time.

Michelle A. Francis:

A long time. Is there a knack to doin' the glazing?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

The dipping?

Nell Cole Graves:

You really got to know what you're doin'. And you got to learn the feel of the glaze, you know, whether it's too thick and whether it's too thin.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. How, what do you look for when you do that?

Nell Cole Graves:

Well, whenever, whenever I'm a'stirrin' it, and I take my hand and let it see if it's a'runnin', if it'd run freely or if it's just drippin'. And if it's just drippin', well, that's too thick. But if you take your hand and stir it, and if you'll let it run, you know, a certain, that's, that's the way you test it.

Michelle A. Francis:

You can tell. In other words, it sort of runs off you but, still leaves a little coat of glaze.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

Aren't a lot of your glazes double dips?

Nell Cole Graves:

All of 'em double-dipped?

Michelle A. Francis:

Aren't some of 'em?

Nell Cole Graves:

Some of 'em are double-dipped. Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Which, what about the brown, the cream and the brown?

Nell Cole Graves:

No, huh-uh. The cream and the brown's one dip.

Michelle A. Francis:

Turquoise?

Nell Cole Graves:

Turquoise's one dip.

Michelle A. Francis:

What you got there? Oh that's pretty.

Nell Cole Graves:

That's our green. Mm-hum. That's a double dip.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's a double dip. This is a green?

Nell Cole Graves:

You dip it in green and then you dip it in white and then whenever it mixes, it looks like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

It gives you the brown on the edge?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's not, now that's pretty. You don't have a whole lot of those.

Nell Cole Graves:

(Laughter) Don't have any out!

Michelle A. Francis:

I was gonna say, I don't remember seein' any.

Nell Cole Graves:

No, it's a lot more trouble.

Michelle A. Francis:

I bet.

Nell Cole Graves:

You got to dip it twice. You got to dip it one time, let it dry just a little bit, and then go back and dip it again.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Did you dip the whole thing twice?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. The whole thing twice.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well then I guess you have to be careful about the texture, the consistency of the glaze there, or you get, you get it too thick.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. You'll get it too thick and then it'd mess up.

Michelle A. Francis:

You must a'made this one, too.

Nell Cole Graves:

I made it. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

It's so thin, I could tell. (Laughter)

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

What's another color that you all make that's double?

Nell Cole Graves:

We make a dapple gray, but I don't have any of that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Waymon showed me a piece of that--a broken piece of that.

Nell Cole Graves:

Dapple gray? It looks gray, uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. That's beautiful.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. But it's a lot more trouble.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you just make these double-dipped glazes for special orders?

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah. We don't, at one time we used to do a lot of it, but we don't now because we just don't have the time.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Are you, who's, is Waymon still doin' most of

the glazin'?

Nell Cole Graves:

He is right now. Mm-hum, but you see, he didn't, let me see when he started back glazin'. After he came from the hospital, and his son came home, he started glazin' then.

Michelle A. Francis:

That would have been, what, two. . .?

Nell Cole Graves:

It's been, uh, about a year and a half.

Michelle A. Francis:

Year and a half.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Bill's his son, right?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

He's been livin' in Florida?

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. Miami, Floirida.

Michelle A. Francis:

Miami. It must be good to have someone else to help around the pottery.

Nell Cole Graves:

Mm-hum. It's good to have him back, yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

He works up some of the clay, doesn't he?

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. He runs it through the press down there. And then he helps uh, put on, the pottery on board at the kiln, you know, and takes it to his daddy, and takes and brings it back to where he glazes and stacks for the kiln. It's a lot of help.

Michelle A. Francis:

That helps, yeah. 'Cause with Waymon's bad hip, it helps not to have to carry all that stuff.

Nell Cole Graves:

Uh-huh. Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

I remember seein' him move it, you know, talkin' to him, seein' him move some of those great big heavy things, and it just scared me to death.

Nell Cole Graves:

Yeah, uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

And I know it's heavy and awkward.

Nell Cole Graves: