[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH DR. THOMAS G. IRONS June 12, 2000

Narrator: Thomas G. Irons

Interviewer: Ruth Moskop

Transcriber: Sabrina Coburn

13 Total Pages

Copyright 2000 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

Thomas Irons - TI

Ruth Moskop - RM

RM : My name is Ruth Moskop. I am here in Room 411 of the Victor Towers Building to interview Thomas Grant Irons about his wonderful family history. Today is June 12, 2000. Dr. Irons, do I have your permission to record this interview?

TI: You do.

RM: Thank-you very much. TI: Thank-you.

RM: We were looking at an article in the North Carolina Medical Journal from...

TI: May/June 2000.

RM: May/June 2000 and it is about your mother. .. TI: And her twin sister.

RM: ...and her twin sister. (0:44, Part 1)

TI: I remember this young woman who wrote the article who was in high school at the time. She had a history day project about women in medicine and interviewed my mother. I think that this was based upon that and upon a Tarheel of the Week article that appeared in Raleigh's The News and Observer about mother's sister, Isa, my aunt. I was commenting that there are about four or five significant factual inaccuracies in that article. I spoke to my mother about them and she said, "Oh, yes. They are all wrong, honey, but she told me that she had to hurry. They made her hurry. She was sorry that those errors were in there, so I don't think that we should anything about it." I said, "Well mother, if they are factual errors, we ought to correct them. We can do it kindly. There's not a problem with doing that." I think my daughter,Sarah, who has graduated from medical school and is starting her Master's in Public Health, which will be followed by residency in pediatrics. I think that Sarah will write a correction to the article, which I think will make a nice, little segway in completion of the circle. It's truly interesting to me that Sarah is so much like my mother and her twin. She is almost an almagamation. I think her twin would, were she alive, would be shouting hallelujah that Sarah decided to get her Master's in Public Health before starting a residency because she had such a keen interest and a career commitment to Public Health. The inaccuracies in the article had some import, at least. For one, one was that the girls were encouraged by family to pursue careers in medicine rather than to do traditional things and the fact was that the girls were very actively discouraged by their family from doing any such thing. There was one person who encouraged them to go all the way and to go for medicine. Other family members thought even nursing wasn't a fit profession for a lady. Their aunts and uncles and grandparents all were strongly opposed to their going beyond college and to doing anything other than perhaps teaching or something along that line, but their father, my grandfather, Thomas Grant, for whom I am named...he was Thomas Macmillan Grant and he was a Methodist preacher. He rotated around Eastern North Carolina and actually was here in Greenville for six years during the World War II years, a very long time for a Methodist minister. He was here at Jarvis Church. He strongly encouraged them to pursue medicine. East Carolina did not offer courses that would even prepare them for medical school. Things like Organic Chemistry, Physics, and so forth. It was a teacher's college and offered early basic science information. The girls decided at their father's encouragement that they would go to Duke to complete a year of studies in order to get the necessary prerequisites to go to medical school, but they did not have enough money. This was also an inaccuracy in the article. The article states that they went to Duke for a year and then, worked for a year and then, went to medical school. What happened was that they did not have enough money to go to Duke to begin with. They already were in debt for their college, which was a very cheap business. They made all of their money typing papers when they were in college. So, they went to work and taught school right here in Pitt County at Chicod School. My mother had one of the current Pitt County commissioners as a student and I won't mention his name, but I will quote my mother. She said, "Son, he never had much sense. He never was very smart, but he always had an opinion." (5:37, Part 1)

RM: Freshman.

TI: Yeah. It was eighth grade that they taught. They then went to Duke and took the necessary courses and made straight A's and applied to Duke to medical school. Their father encouraged them. They were rejected on grounds of frailty and stayed up all night that night typing their applications to Medical College of Virginia and Women's Medical College of Philadelphia mailed them in and were accepted immediately. So, they went to Richmond.

RM: What a heroic story that is. Tell me, I interrupted the tape just a moment. Here we go. Tom, I have two questions for you. One of them, why do you think your grandfather Grant was so interested in having his twin daughters pursue a career in medicine? (6:33, Part 1)

TI: Well, I think that is very interesting. It certainly was not what a minister would normally would have been expected to do. His wife had died when the twins were born within a matter of days after the birth, probably of a pulmonary embolism. That's what they believed now happened. She died suddenly. She was gone. The twins were saved by a wet nurse and by some creative people who knew how to dream up diluted cow's milk to add to what the wet nurse bought. They were small, thin babies who really struggled. I think to some degree, at least, he saw his wife in them. Apparently, she was a very strong and both an intelligent and a capable woman. I think the history of her brothers would uphold that. Her brother, Isaac, was a very prominent historian at Harvard, who died young, prematurely, I believe of lung cancer. Her brother, Costen, was a bishop in the Methodist Church and was last bishop of the Atlanta area before his retirement to the faculty at Emory and so forth. She came from thinking people and apparently, was a really an unusual and very strong woman married to a typical Scotsman. A big, redheaded man who loved the outdoors and who proclaimed on the porch of a house when my mother was a little girl that a man's relationship with his horse would never allow the automobile to make it. But, I think that was part of it. I think he saw something in them; some great strength in them; some power in them that would go beyond what was normally available to women in those days. So, I think it was in part there. He had remarried when they were five or six years old. They moved back if I remember correctly...My mother, I'm sure has that correct. They moved in...they lived with their grandparents up until then. Their uncles had a powerful influence on their lives, too. The one that I didn't mention, Uncle TC, was the Treasurer of Greensboro College. But, they moved back in with their father and his new wife and there was one child of that union. So, their teenage years were spent with their father and it sounds like they had a very happy relationship and a very deep affection for their father. It was a good humor sort of thing. My mother loves to tell of being in the balcony in church in Wilson, when he had the church in Wilson, and having him call them down from the pulpit by name for cutting up in church and how humiliated they were. So, the woman I always thought was my grandmother, the woman that my grandfather married later, I remember as a lovely lady who loved to read stories to us. We sat and read stories a lot. At any rate, I think that he wanted them to...he saw something in them and believed that they had potential to do something big. (10:31 Part 1)

RM: And he thought of medicine as a respectable profession, clearly a very highly respected position.

TI: Yeah. He did. And I think, clearly was not a man who was caught up in the various sexual stereotypes of the time. He could see a woman in that role, where so many people didn't. Frailty was the common pronouncement. There is a story of Isa that is really telling in that regard and it also inaccurately or not reported in the story. But there is a comment that another one of the physicians mentioned in the story, Dr. Disosway, a really heroic physician ...had a proposal of marriage, but never married.

RM: Clarify that name again, Tom. (11:25, Part 1)

TI: It's the other physician referred to. It's Lula Disosway, who was one of the...another woman pioneer in North Carolina medicine, commented that she had a proposal, but never married and was always in the mission field. Isa, having recovered from her tuberculosis, but having spent a long time of what was then the sanatorium, which is inaccurately reported as a sanitarium in here. And in the sanatorium up at the tall one subsequently working there had a proposal from a Presbyterian seminarian in Richmond, who was from New York. My mother says that they were very excited about the marriage and that his father rejected the marriage proposal outright and they broke it off. His father, who was a New York investment banker, apparently believed that his marrying a frail woman who had had tuberculosis would be a story right out of opera and she would end up like Carmen. (12:38, Part 1)

RM: Dying of consumption.

TI: Dying of consumption and that's how he painted it. Of course, consumption is not what ki1led Isa Grant, plain old ovarian cancer is. But, she proved herself hardy. Interestingly, Isa always looked a little frailer, a little paler. She was more fair and a little thinner and a little quicker with her tongue than my mother. My mother talked more, but Isa was sharp and quick and witty with a comeback. She had several romances, none of which worked out much to her sadness, but ultimately was quite resigned to being the single woman. She took in a number of orphans from the Oxford Orphanage. Excuse me, was it Oxford or Methodist? I believe it was The Oxford Orphanage and from The Methodist Retirement Home. As they graduated from high school, she took them in so that they could have a year of transition before they went out into work and so forth. But, she also played a major role in raising all of us. We used to feel like we had three parents and a vacation was my mom and my dad and my mom's twin sister in the front seat and the three boys in the back, if we ever had a vacation, which wasn't all that often.

RM: I understand there was some concern in the Grant family when your mother and father decided to marry... (14:20, Part 1)

TI: Yes.

RM: ...about Isa being left out.

TI: That's exactly right. That's exactly right. In fact, lsa was...actually had dated my father before my mother, which is interesting, too. Yes, they did, because they felt like they were, the two of them, were a team and that they must always function as a team. They were up at, every morning that I can remember, they called each other at 6 or 5:45, at least more mornings than not, they did. So, they were very, very close. Like all identical twins, they had certain things that they shared. They gave speeches together in which they simply took off on each other without any noticeable transition. It just sort of went.

RM: Like a continuing conversation.

TI: Yep, exactly. But, they were different people. Goodness, Ruth. My mother is volatile, really quite volatile. You would not guess it now. She appears almost sanguine at this point, wise in her old age. But, she is quite volatile and Isa knew how to get her goat. (15:45, Part 1)

RM: She had to.

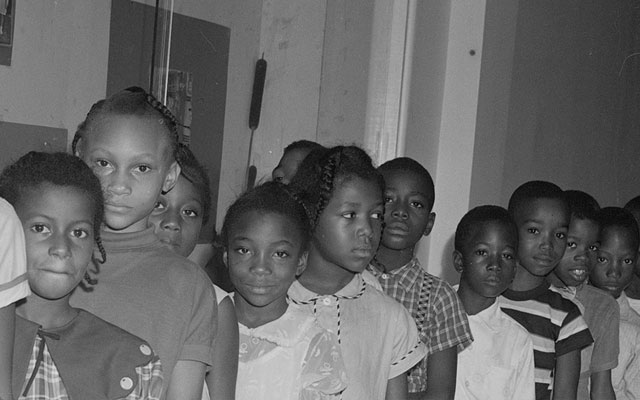

TI: Yeah, exactly. She would not hesitate to get her goat until they were 50 years old. I could still see Isa just twisting that little witticism right in and putting the barb right in and my mother just exploding with anger over it over and over. They traded off back and forth like that. Then, of course, all was forgiven and they were back at work side by side on the porch painting watercolors or whatever it is they did. They had a very...the commitment in their family to service is very, very powerful and their belief in social justice is very powerful. They were traditional in many ways, but we were taught very early in our childhood not to use racial stereotypes in our home. I'm not referring to things like nigger. That word was never said in our home. I am referring to, "we're not going to use the term of colored anymore, we're going to use the term, Negro and we're going call the maid, Ms. Knox and not Mary and so forth." That was way long before that sort of thing was popular. They had a complete passion for it and of course, my father is such a deeply private man and a very quiet man, a man who was brought up in ....they were both brought up in conservative religious environments. One in a Methodist preacher's house, where you didn't play cards on Sunday and you didn't go to the movies on Sunday and those sorts of things. But, there was a certain looseness about it that made it all fun. It was that Southern version of it. My father came from a much more severe Calvinistic sort of background where guilt was... (18:00, Part 1)

RM: A major factor.

TI: ...a major factor. He always felt like he couldn't possibly do enough and he wouldn't ever be able to do enough, which I believe and I have no embarrassment about this being part of the permanent record. I believe the major reason for his depression from which he suffered when he got older. He never felt like he could ever do enough to be a good Christian; to be a good whatever, a father.

RM: Did he feel like that he had been blessed and he needed to return.

TI: Oh, there are times when, but, it was duty. It was just duty, duty, duty. He lived his whole work life with duty. Dr. Fred is known to people who worked closely to him as a man of good humor, quite a character who enjoyed and always had a good time with the staff. That was hard to see from my side of the fence. He was a very busy, almost severe, man, very focused on his...he was certainly not abusive towards us. In fact, he was a very gentle and loving father, although, he was a disciplinarian when we were young. But, there was very little intimacy in the relationships until we got older. (19:42, Part 1)

RM: He told us that his mother and his grandmother had raised him.

TI: That's correct. His grandfather was Benjamin Franklin Irons and he was a physician who practiced in Pickaway, West Virginia, which is very close to Rockridge Bass, Virginia. His father was a farmer and his mother was a schoolteacher and very well educated. Sally Gibson was her name. They had four children and she left him. She left him when he, as the family records put it, broke down. He was an alcoholic and whether or not there had been abusive episodes or whatever is not clear. She packed up the children and left and he stayed right there in the little town. He stayed right there. He ultimately was to move with his unmarried sister and his married sister in Concord, North Carolina, where he would die. He apparently had serious issues of depression as well and alcoholism. He died there many years later. I can barely remember his face. I only saw him once or twice that I remember. She farmed out the children. Dad went to his...shoot...an aunt and a single daughter. He took care of their farm, their little bit of farm. It had cows and such and helped them. His sister, Evelyn, went to another aunt, who was known as Aunt Mary John, all right there in the same community. His little brother, Ben, was the only one who stayed with his mother. His sister, Sarah, went to an uncle, who was named, Uncle JD. Uncle JD moved to San Diego, so Sarah went to San Diego. She spent her whole life in the San Francisco Bay area. She married there. Her husband died many years before she did. She ultimately developed Alzheimer's and had a tragic ending to her otherwise happy life. His baby brother, Ben, had a career in the Air Force before retiring and taking a job at the Social Security Administration. So, that's the...Aunt Evelyn is his older sister, who's 89 and has just drifted over to the functional point where she needs assisted living up in ( ), Virginia.(23:10, Part 1)

RM: Tom, did your dad and mom tell me that those aunts who raised your dad, did they enjoy music in some particular way?

TI: Yes. And he...yes, they did. I can't remember. What I remember is, that Grandfather Gibson, who lived right up the road, my grandmother's father, played the fiddle and that several of the children were musical. Dad did not have any

musical talent, but he enjoyed music. My grandmother loved music and when she stayed with us and that was more often than not, about six months out of the year.

RM: What was this grandmother's name?

TI: This was Grandmother Sally Gibson Irons. RM: Sally Gibson Irons.

TI: Right and Sally Gibson Irons would come and stay with us. She was really a rather severe woman, I thought. Calvinist, through and through. We had to memorize a catechism. She had Robert E. Lee's picture beside her bed. She kept collaring the poor maid and telling her that the Civil War was not fought for slavery and she was the local secretary of The United Daughters of the Confederacy. She did have a wit about her. She was a rather clever woman. She loved to dance and sing and dance. When we were little, she would dance with us around when we played our little records and stuff. My dad had a big...this is something really odd, I think. It may be interesting. My dad had a...and it came up this weekend. It's funny that you should mention it. My dad, we had a nice record player and my dad had a big collection of symphonic music and we had to sit and listen to Peter and the Wolf or the...I have forgotten where you learn about the instruments, the orchestra and so forth. (25:13)

RM: Carnival of the Animals?

TI: Carnival of the Animals. Right. We loved that music, although, we didn't have to sit and listen. My father and my mother got too busy to listen to music. It was gone. When that record player went out ...shoot, that was in the fifties. Somewhere in the late fifties, when hi-fives came along, my brothers and I got one for Christmas, just a little cheap hi-five, so we could play our new Elvis Presley records on them, but my parents didn't have one. And because Dad worked until 9:00 at night, almost every night or Mother was exhausted. They came in ...she was taking care of us in the evenings a lot. They would come in and read their journals, get ready for Sunday school and that was it. It seemed to me that they were not even reading anything other than religious books or books related to their church. For 25-30 years, they just worked. I went down in the basement as I was cleaning out their house, which is terribly sad time, particularly for my dad. He couldn't stop crying and he sat out on the porch in a chair. We had to help him out of his chair and get him in the car. That was not even our original home. That was a home we moved into when I was in high school. We lived right downtown in an old house, nothing fancy about the Irons'. I tell you. People accused me of being wealthy because I had two doctor parents and here I was living in this old downtown house with almost all of my neighbors being poor people. (27:18, Part 1)

RM: Where was that house?

TI: It was on East Eighth Street. It was 204 East Eighth Street. That part of Eighth still exists. The major part of East Eighth was obliterated by the college. The New Student Activity Center is right on top of it and Mendenhall is right on top of it. It right straight down to the library, all the way to the old Joyner Library. RM: Your mother had an office close to that home.

TI: Well, the way it started, Ruth, they bought the Person house, which was on the comer of Eighth and Evans, which is directly across from what is now the Greenville Museum of Art. The Person house was a two-story brick structure with four bedrooms upstairs. It was a good-sized house. It was that very dark looking, very rough brick of the time.

RM: Almost brown.(28:20, Part 1)

TI: Yeah. Almost brown. A very, very dark red, a rough looking, drab-looking brick. It had a cinder parking area in the back, which was paved with the cinders from the coal-burning furnace. It had an automatic feed coal furnace in it. Her office was downstairs and we lived upstairs in the ( ) reverse sort of thing. When I was five years old, just I guess maybe four, because I am not sure my little brother, Fred, was born yet. But, we moved up the street and bought the Gaskins house, the house that Charles Gaskins and his brothers and sisters were born in up the street. It was only four houses up Eighth Street on the right side. That house does not exist. There's some sort of student center, maybe a Christian Student Counseling thing or something there. It's a little one-story brick building. On the comer of Eighth and Cotanche is a parking lot and just down from that is the building. We were right there. Back and forth to the office was a little run down the street. Everybody on the street I knew. I felt raised by all of those people and they the same. A lot of college students lived there. My mother rented out the space upstairs in her office when we moved to married college students, who would stay up there and share a bath, you know and get along with nothing. But, that allowed her to be very close. (30:26, Part 1)

RM: She was the student housing authority.

TI: Right. She could be very, very close to us. We were in the office as little children; at least as much as we were at home. Earl Trevathan told me when he went over to meet my mother; I was playing under the examining table in the room where he was meeting her. Of course, it's resulted in our being exposed to everything infectious under the sun very early in life. All of us had measles before we were a year old. All of us had chicken pox before we were a year old and so forth. But, we lived right there. We had a whole series of maids, cooks, and caretakers who often functioned two at a time. One to take care of the children, especially when we were very young and one to take care of the household work. If both parents were at risk of having to leave in the night, someone slept in and so that we always had somebody sleeping there with us. When my mother went to the hospital in the evenings to make her rounds, at least as often as not, we were in the car with her. (31:50, Part 1)

RM: Which hospital would that have been?

TI: Well, although Ben and I were born in the old hospital. Fred was born in the new hospital. I don't remember as a child ever going to the old hospital other than to be born. I mean other than to...

RM: When you say the old hospital. ..

TI: That was over on Fourth between... RM: And Johnston?

TI: Yeah. I do remember it. When I was in high school, it was the Welfare Department. It was still in that old building. That hospital, I remember very little about, other than I had been born there and that my mother had been going there when Ben was born. I do remember the stir mother caused when she not only breastfed her babies, but she also came home from the hospital in two days. They made a big production of it; bought her home in an ambulance and so forth. (32:55, Part 1)

RM: Would she have had a general anesthetic at that time?

TI: I would guess almost surely. Almost everybody did. In fact, Dad was adapted...he was doing a lot in anesthesia. He did a lot of anesthesia and doing a lot of deliveries as well, supervising the anesthesia while the nurse passed the gas and doing the deliveries. He did anesthesia. They had so little income when they got here that he did anesthesia in the mornings before work. Well, he made his hospital rounds very early. Then, he did anesthesia. Then, he went to the office. Then, he went to the infirmary and then, he came home. That's how they pieced together an income. She told me that for at least a year, she had almost no referrals and that the male doctors would not give her a patient and that it all happened by word of mouth. When the word got out that she was here and she knew what she was doing that it all happened and she got extremely busy. She got so busy it nearly did her in, I think. When she left practice and went to the DEC back in about '62 or so, she and her sister had dreamed up this idea, ( ) decided that we needed to deal with child development issues and that there was a serious problem in our state. They talked to Governor Hodges, I believe. They went and met with him and proceeded to wiggle some money out of him to start these developmental evaluation clinics. She became the first director here. (34:41, Part 1)

RM: So, it's a system throughout the state? TI: Yes.

RM: See, I wasn't aware of that.

TI: Yes. They are all over. There's one in Elizabeth City, one in Rocky Mount, and I think there's still one in New Bern. They operate their staff to varying degrees. But, yes, it is a system throughout the state and it gave her no night call and a chance to be with her family again.

RM: How old were you by the time that happened?

TI: I was almost out of high school. It was my junior in high school when she left that. She was good about some things. Ifl had a swimming meet, she'd come warring in about five minutes before the time when she thought I was going to swim, watch me, cheer, and be the hell out of there. Bless her. And of course at that time, you almost were embarrassed for your parents to even be around. So, that was fine with me. She did a lot of that sort of juggling. But that backseat, God knows, I have sat in that backseat all the way or graduated to the front, drive out to the hospital, sit out there for two hours, three hours, you know the feeling. Then, go off and make house calls, maybe. (35:58, Part 1)

RM: She mentioned that she took you boys to Duke with her as well, when she would go carry patients of her own.

TI: Yeah. Yep. Exactly, she'd go take patients and we would be in the call with her. That's how she got to know the allergist doctor, Susan Dees up there and how we ended up getting our own allergy testing done by Dr. Dees, who was quite a character and I think may still be living. She's probably 95, if she is, but I've heard she's still around. Yeah. Oh, yeah. We did almost everything with her. Of course, the vacations that we had were often to medical meetings. Our one or two New York trips, our Richmond trips, and they would go to the AMA and we would take a train. Of course, the three of them would go to the meeting. Usually, not the two of them, but the three of them, Isa, Malene, and Fred would go and we would get to see the city and go to the Empire State Building or whatever it is you want to do while they went to a meeting. I felt ...you know you grow...I'm so proud of what they are and what they stand for and I don't think I would trade anything. It's sad that we weren't able to have the time to play together, but we didn't. We played with Isa. Isa was just a player. One time she was keeping little Thomas when he was four and Sarah, who was two while we went off somewhere shopping. She and Thomas decided they would make a big fire by burning all the Christmas wrapping in the fireplace and it got so hot and so fast that fire came out of the fireplace and scorched the underside of the mantle. That was just typical of them. They would do some crazy ass thing like that. Of course, then they had to conceal it and clean it all up and it was just typical of her. She was always... (38:15, Part 1)

RM: This is in you and Carol's home.

TI: Yeah, in our home. But, we did have a few vacations, but the older we got, the less frequently it happened. Ben and Fred went off on vacation with Isa and two of their cousins, Isa's cousins and my mother's cousins all the way to California. But, I remember being too old to make that trip. I had to go to Boy's Scout camp. I was twelve years old. But, we had the wonderful house on the river and I have nothing but happy memories, but by the time I was ten, we hardly ever went. If we did go, it would be that one time of the year for two weeks. The rest of the time or did not go at all. Weekends did not belong to them anymore and so, we just didn't get to play together. My dad would try his best and he would buy a boat and he'd get out to try to learn how to drive it and take us on a boat ride, but he couldn't last very long. I remember him trying to take me hunting, trying to take me fishing, things that he had never done or hadn't done in years and it just not working. It just was uncomfortable. So, I missed that. I happened to marry a woman who's family loved to play and did a lot of those kinds of things together. So, that turned out to be a place where I could really enjoy that. But, a life of sacrifice can be punishing. It's very hard to find a balance and I think for people of their generation, it must have been particularly hard to find a balance. So, they didn't. They just roared on as hard as they could. Very, very loyal members of their church, very much focused on that part of their lives. So, they did have one other thing that they did besides work. I remember thinking when they finally stopped at the country club...I feel sure they were the only doctors who were not members of the country club at the time... they stopped because they never ever, ever went. They never had gone. They didn't ever drink alcohol. They never went to parties of that nature, but they kept it while we wanted to use a swimming pool and then it sort of dawned on them that was not really necessary anymore, so they just quit. We followed them in their footsteps a good bit earlier. Carol and I quit after we had been here about six or seven years. We just felt like it wasn't something we needed to do. (41:17, Part 1)

RM: No need for it.

TI: Yeah. Ridiculous expense.

RM: Well, Tom, you needed to wind down this conversation about now. TI: Yeah. I sure did.

RM: May we continue in a few days?

TI: Yeah. I would just love to. I would love to get back to a few of my thoughts about how they...their residency of that whole period and their period there in Richmond is really interesting to me and what they had to live through during the war and running the hospital alone. As my mama put it, "Just us girls and a bunch of old women." I mean old men. Old men and a bunch of girls, who kind of kept the place going.

RM: You can probably share stories about Isa and the sanatorium as well... TI: Yes.

RM: ...and that aspect. TI: Yes.

RM: I understand that you assisted your mother. I think she told us in some cases with her pediatric patients at a young age. (42:18, Part 1)

TI: Ruth, I think I was not twelve because I was not allowed to come in to the in� patient wing before I was twelve. That was a hospital rule. But, my mother slipped me in, because she didn't have anybody to help her hold this patient for a spinal tap. I held a baby for a spinal tap for tuberculermeningitus everyday. Tuberculermeningitus is unique in that the pressure has to be relieved through daily spinal taps. It obstructs the flow of spinal fluid and it's terribly prolonged difficult disease to treat. So, the baby had to be tapped everyday. My mother, who has the shakes now something awful, was, I never saw anything like the way she could slip a needle in. And these great big needles with big, heavy metal stopcocks and big syringes, which is all they had then to use.

RM: They had to be sharpened each time they... (43:28, Part 1)

TI: Oh, yeah. And could deftly pop that thing in there and get that spinal fluid out. Oh, yeah. I held babies for her. I knew long before I was twelve years old that I was a doctor. It never occurred to me that I could be anything else or that I would want to be anything else. I just was. It wasn't that I had an aspiration. I already was. I knew what I was and this is what I have to do to be what I am. I do miss the fact...I majored in English. I love the word. I love to read. I love to write. I do sort of miss that. I kind of jacklegged it by doing that on the side while really busily knocking off the right grades on my pre-med courses so I could go to med school and once I went to med school, I really completed abandoned it. It came back finally, but it was long after. But, anyway, yeah, I always knew I was a doctor. And Ben didn't. I don't think he ever had that clinical interest that I did. He wasn't really interested in holding patients. He was interested in football. He was interested in history. He was fanatical about history. He wanted to learn everything there was to learn about the Civil War. So, he had other, more traditional boy interests in ...I would have thought Fred, who's a very thoughtful, introspective kind of guy... (45:28, Part 1)

RM: More like you dad, maybe.

TI: Yeah. Very much more...would have been the one who would be a psychiatrist. In fact, I thought he could be a minister. He looked like he had that career lined up. He was President of the State Methodist Youth and so forth. I think he chose exactly the right career.

RM: Was that psychiatry?

TI: He's as good as a psychiatrist that I've ever seen. He so capable and he is so even. He's rea11y done marvelously well. You wonder what it is. I feel like I've given ...talking about Sarah and having worrying over people feeling like they have to live a life of sacrifice. It's a terrible burden that I personally bear that I always wrestle and wrestle with the inevitable guilt and depression that come when I feel as if I've not met standards that I continue to raise for myself at all times. It's caused me to have some significant depressive problems as it certainly has my mother and even my dad.

RM: You set high standards.

TI: Yeah. Well, Sarah is doing the same damn thing. She will not stop pushing herself and is never satisfied that she's not kept everybody happy and... (47:01, Part 1)

(Tape Ends)